In March, General Bosco Ntaganda, the ‘Terminator’, former chief of military operations for the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC), wanted for war crimes and crimes against humanity, voluntarily surrendered himself at the US embassy in Kigali and was flown to the headquarters of the International Criminal Court at The Hague. The chargesheet included accusations of murder, rape, sexual slavery, persecution and pillage, offences documented in detail by Human Rights Watch over the last ten years. Ntaganda’s trial, scheduled for next year, will follow that of Thomas Lubanga, the UPC’s president, who was convicted in 2012. There seems to be no question about the justice of the proceedings. At the same time, however, the UN Security Council has been pursuing a strategy of armed intervention in eastern Congo, using troops from South Africa and Tanzania, against the rebel groups Ntaganda and others commanded. Both initiatives – the prosecution of rebel leaders for war crimes and military operations against their personnel – are taking place when peace talks between government and rebels are well underway. This, then, is a co-ordinated military and judicial solution for what is also, and fundamentally, a political problem. Inevitably with such solutions, the winners take all.

Where mass violence is involved, there is always a choice between the judicial approach, enforced by the victors or by external powers, which tends to exclude the losing parties from any political settlement, and negotiation, which necessarily involves all parties in discussions about the future, whatever the crimes they have committed. After the Cold War, our response to mass violence has largely been determined by the model of Nuremberg: in Rwanda or Sierra Leone, Congo or Sudan, international criminal trials are the preferred response. The problem here is that mass violence isn’t just a criminal matter, since the criminal acts it involves have political repercussions.

This is not to say that no one should be held responsible for violence, merely that it is sometimes preferable to suspend the question of criminal responsibility until the political problem that frames it has been addressed. The clearest alternative to the Nuremberg model that has emerged since the trials concluded in 1949 is the complex set of negotiations known as the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), which brought an end to apartheid in the 1990s. (It’s worth bearing in mind that D.F. Malan’s National Party embarked on its 45-year racialist experiment in South Africa while the Nuremberg courts were still in session.)

Contemporary discourse on human rights is silent about the end of apartheid. The tendency is to reduce this remarkable development to the single, exceptional personality of Nelson Mandela. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is lionised but Codesa is largely forgotten, and Africa’s abiding problem – violent civil war – is said to require a different solution: the atrocities committed are so extreme, the argument goes, that punishment must come before political reform. Nuremberg-style criminal justice is the only permissible approach. But there are lessons to be learned from Codesa, and its language of compromise and pragmatism, for present-day conflicts in Africa.

Nuremberg was the result of a debate among the victorious powers on how to deal with the vanquished. Churchill argued that the Nazis had forfeited any right to due process and should be summarily shot. Henry Morgenthau, the US Treasury secretary and a close friend of Roosevelt, agreed; he went further and said that Germany’s industries should be dismantled so that it would never rise again as a world power. Henry Stimson, Roosevelt’s war secretary, took a different view. So did Robert Jackson, a Supreme Court justice, though Jackson was clear that ‘you must put no man on trial under forms of a judicial proceeding if you are not willing to see him freed if not proven guilty … the world yields no respect for courts that are organised merely to convict.’ Truman was impressed by Jackson’s speech and three weeks later appointed him as Nuremberg’s chief prosecutor.

The credibility of Nuremberg was based on its claim to due process. For their part, the accused preferred to be tried by the US than by anyone else. They expected softer treatment from Americans partly because the Americans had for the most part enjoyed a grandstand view of the war, and partly because they were likely to be allies of Germany in the coming Cold War. The trials also need to be understood as a symbolic and performative spectacle. For Washington, Nuremberg was an opportunity to inaugurate the new world order by showcasing the way a civilised liberal state conducts its affairs. With the air full of cries for revenge, Jackson told his audience at Church House in London: ‘A fair trial for every defendant. A competent attorney for every defendant.’

The accused were charged with four crimes: 1. conspiracy to wage aggressive war; 2. waging aggressive war (together these charges were referred to as ‘crimes against peace’); 3. war crimes (violations of the rules and customs of war, such as mistreatment of prisoners of war and abuse of enemy civilians); and 4. crimes against humanity (the torture and slaughter of millions on racial grounds). The concept of crimes against humanity was first formulated in 1890 by George Washington Williams – a lawyer, Baptist minister and the first black member of the Ohio state legislature – to describe the atrocities committed by King Leopold’s regime in Congo Free State, and it was this charge that made Nuremberg the prototype for what has come to be known as victims’ justice. Nonetheless, conspiracy to wage war and its actual waging (1 and 2) were defined as the principal crimes on the Allies’ chargesheet: crimes against humanity were subsidiary. The Allies were divided on this order. The French disagreed that waging war was a crime in law: it is what states do. The Tokyo trials took more than twice as long as the trials of the principal figures at Nuremberg, partly because of substantial dissenting opinions. Justice Radhabinod Pal of India argued that conspiracy had not been proved; rules of evidence were biased in favour of the prosecution; aggressive war was not a crime; and the judgments were illegal because they were based on ex post facto grounds. The trial, in his view, was a ‘sham employment of the legal process’.

A more serious problem arose from the fact that only the losers were put on trial. The victors appointed both the prosecutor and the judges. Didn’t Truman’s order to firebomb Tokyo and drop atomic devices over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to untold civilian deaths when the war was already ending, inflict ‘gratuitous human suffering’ and constitute a ‘crime against humanity’, to use the language of the court? Hadn’t Churchill committed a crime against humanity when he ordered the bombing of residential areas of German cities, particularly Dresden, in the last months of the war? Most agreed that the British bombing of civilian areas killed some 300,000 and seriously injured another 780,000 German civilians.

The emphasis on the last of the four charges, crimes against humanity, began to fade as the trials drew to a close: the beginning of the Cold War marked a change in US attitudes, away from the imperative of retribution towards accommodation. The fate of Alfried Krupp was a clear-cut instance. By the First World War the Krupps were Europe’s leading manufacturers and suppliers of guns and munitions. During World War Two the family business owned and managed 138 concentration camps across Europe. The family used slave labour to build and man their factories and arm Germany: they were allowed to select workers from concentration camp inmates and prisoners of war and to requisition factories in occupied countries. In 1948 Krupp was charged with crimes against humanity and sentenced to 12 years in prison. Two and a half years later he was released and his assets restored in an American-led amnesty.

Central to the kind of justice dispensed at Nuremberg was the widely shared assumption that there would be no need for winners and losers (or perpetrators and victims) to live together in the aftermath of victory. In a short period of time, the Allies had carried out the most far-reaching ethnic cleansing in the history of Europe, not only redrawing political boundaries but moving millions across state boundaries. The overriding principle here was that there must be a safe home for survivors, and in 1948 the state of Israel itself became a model for the form of restitution to which survivors were entitled. The term ‘survivors’ is itself an innovation of post-Holocaust language: it applies to yesterday’s victims, whose interests must always be put first in whatever new political order follows a period of mass violence. In Rwanda today, as in Israel, the state governs in the name of the victims.

Nuremberg was ideologised at the end of the Cold War. Stripped of its historical and political context, the ‘lesson of Nuremberg’ was turned into a prescription: criminal justice is the only politically viable and morally acceptable response to mass violence. As the paradigm of victims’ justice, Nuremberg became the cornerstone of the new human rights movement. But there is one inescapable characteristic of victims’ justice: a defendant is either innocent or guilty. And it follows from this approach – which may be wholly appropriate in an apolitical context, where the future of a society doesn’t hang in the balance – that perpetrators who are found guilty will be punished and denied a life in the new political order. This can be a dangerous outcome, as South Africans on both sides knew when they sat down to negotiate the end of apartheid.

It has become a commonplace that the South African transition was led by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The TRC was set up as a surrogate Nuremberg in which the opponents of apartheid sat in judgment over its operatives. As with Nuremberg, the TRC’s claim to have granted amnesty in return for truth-telling should be seen as a performance. For one thing the TRC process individualised the victim, which made symbolic but not political sense, since it was precisely the legal definition of entire groups as ‘racial’ communities that made apartheid a crime against humanity. For another, the TRC defined a human rights violation as an act that violated the individual’s bodily integrity, when most of the violence of apartheid had to do with the denial of land and livelihood to large populations defined as inferior ‘racial’ groups (forced removals, pass laws and so on). At the TRC the normative, institutional violence of apartheid took second place to the spectacular violence experienced by far smaller numbers of leaders and activists and carried out by perpetrators whose actions were seen as a matter of personal responsibility.

The TRC displaced the logic of crime and punishment with that of crime and confession. In fact it set aside the violence of the apartheid state – which was enshrined in law, if not legitimate – and focused on the excesses of its operatives. And crucially it held individual functionaries criminally responsible only for violent actions that would have constituted crimes under apartheid law. Other acts – ordering the demolition of homes, for instance – were deemed to be lawful. The TRC was in this sense quite unlike Nuremberg, where the laws of the Reich were never used in mitigation of a criminal act. For this reason, the TRC was unable to compile a comprehensive record of the atrocities committed by the apartheid regime, as Nuremberg had for the crimes of the Nazis. The TRC was essentially a special court, convened in the shadow of apartheid law, whose work did not address the legalised exclusion, oppression and exploitation of a racialised majority.

In his foreword to the TRC’s five-volume final report, published in 1998, Desmond Tutu celebrated the commission as evidence of the ethical and political magnanimity of the victims, but the real change had taken place before the TRC was set up. Codesa had also promised amnesty to the perpetrators of violence, though not in exchange for truth-telling but, crucially, for joining the process of political reform. The negotiations were conducted with the aim of ending political and juridical apartheid. They involved inevitable compromises on both sides, without which the transition could not have been achieved.

Codesa was a recognition by both sides that there was little prospect of ending the conflict in the short term and that this meant each accepting that its preferred option was no longer within reach: neither revolution (for the liberation movements) nor military victory (for the regime). If South Africa is anything, it is an argument for moving swiftly from the best to the next best alternative. The ANC were quick to grasp that if you threaten to put your opponents in the dock they will have no incentive to engage in reform: far from criminalising or demonising the other side, as it must have been tempted to do, the ANC leadership decided to treat it as a political adversary. Trials embody the ideal of justice, but the criminal process eliminates the people whose co-operation is needed to negotiate an end to the conflict. However unspeakable, the violence in South Africa was a symptom of the deep divisions in civil society that drove it. Nuremberg-style trials would never have addressed these divisions. And there would be no Israel for victims: victims and perpetrators, blacks and whites, would have to live in the same country.

Codesa unfolded in fits and starts. During the first phase, which began at the end of 1991, each side tried to muster a consensus – or at least a clear majority – within its own ranks. In March 1992, following a series of by-election victories for the ultra-right Conservative Party, which had refused to be part of Codesa, the ruling National Party called a whites-only referendum on the state of negotiations so far: an overwhelming majority approved of the process. Codesa II got underway in May, but was thrown into disarray by the Boipatong massacre the following month: Mandela accused the government of complicity with the Inkatha Freedom Party killers and the ANC withdrew from the talks, embarking instead on a ‘rolling mass action’ campaign, which brought the movement out on the streets. Bilateral negotiations between the ANC and the NP eventually resumed despite the formal breakdown: each side had used political violence, and the threat of more, to mobilise its supporters and paralyse the opposition, a strategy that underlined the urgency of talks. In September the two sides signed a Record of Understanding: a democratically elected assembly would draw up the final constitution, within the framework of principles agreed on by a meeting of negotiators appointed by all parties.

As the ANC prepared to make historic concessions, Joe Slovo, the general secretary of the Communist Party, wrote an article in the party journal, the African Communist, proposing a power-sharing arrangement. As part of the deal, the bureaucracy of the ancien régime (including the police, the military and the intelligence services) would be retained and there would be a general amnesty for apartheid enforcers in return for full disclosure of their deeds. Slovo did not need to state the obvious: the real quid pro quo for these concessions was not transparency about the regime’s murderous past but a comprehensive dismantling of legal apartheid and the introduction of electoral reforms that would pave the way for majority rule.

A ‘multi-party negotiating process’ began on 5 March 1993, driven forward by the two main protagonists, the NP and the ANC. Things got off to a sluggish start but once again political violence – this time the assassination of the ANC/SACP leader Chris Hani – concentrated minds. The parties agreed on 1 June that elections would go ahead the following year, in April. The shared sense that storm clouds were gathering made it possible to truncate discussions on fundamentals such as constitutional principles and the fine points of the constitution itself. The result was an interim constitution, ratified in November. Key decision-making power was delegated to technical committees (to be assisted by the Harvard Negotiation Project), in order to forestall or break deadlocks in the negotiations. With the interim constitution, the protagonists – and the country – reached a ledge in the course of a rapid and dangerous ascent. The slender legitimacy of ‘sufficient consensus’ was the justification that allowed the ANC and the NP to keep up momentum. The fact that binding principles had been agreed on by unelected negotiators, and that the constitutional court had been given power to throw out a constitution drafted by an elected assembly, were flagrant violations of the democratic process. Yet growing numbers of South Africans came to see them as a political necessity.

The constitutional principles that emerged included a number of key provisions. The first was the independence of the Public Service Commission, the Reserve Bank, the public protector (an ombudsman), the auditor general, schools and universities. The second was a constitutionally guaranteed Bill of Rights that enshrined private property as a fundamental right. The clause providing for the restoration of land to the majority population was placed outside the Bill of Rights. Where property rights were in contention, as they were between white settlers and black natives, the former appeared to enjoy a constitutional privilege as a result of the Bill, the latter only a formal acknowledgment of ‘the nation’s commitment to land reform’. Even greater concessions were made at provincial and municipal level, with hybrid voting systems that precluded absolute black majority control in local government and made it impossible for taxes to be levied in white areas for expenditure in black areas. White privilege was, in effect, entrenched in law in the name of the transition. The outcome of Codesa was mixed. It traded criminal justice for a political settlement and offered a blanket amnesty in return for an understanding (‘sufficient consensus’) that led inexorably to the dismantling of legal apartheid. At the same time, it put a constitutional ceiling on measures of social justice that would have allowed majority rule to propel dramatic or meaningful change.

The Nuremberg trials ended in 1949 with the Cold War in full swing; Codesa convened two years after the Cold War was formally concluded. Clearly the kind of realpolitik in play during the closing stages of Nuremberg was also a defining force in the Codesa experiment, but the paradigm had undergone a radical change from the pursuit of victims’ justice to what might be thought of as survivors’ justice, if we take the term ‘survivors’ in the broadest sense to include everyone who emerged from forty years of apartheid: yesterday’s victims, yesterday’s perpetrators and yesterday’s beneficiaries-cum-bystanders.

South Africa’s transition was preceded by a political settlement in Uganda at the end of the 1980-86 civil war. The outcome of the war was a political stalemate: one side, the National Resistance Army, had ‘won’ militarily in the Luwero Triangle (a small part of the country) but had no organised presence elsewhere. Political resolution took the form of a power-sharing arrangement known as the ‘broad base’, which gave cabinet positions to opposition groups that agreed to renounce the use of arms. Contrast this with the Ugandan government’s perplexity in the face of a more recent insurgency led by the Lord’s Resistance Army. The International Criminal Court issued warrants against LRA leaders in 2005, a fact that makes an inclusive settlement difficult: the combination of continuing armed hostilities and the court’s involvement appears to have ruled out any political deal for the moment. All the government can do is to ensure that the LRA’s military campaign is exported to neighbouring countries.

In Mozambique, six months after the South African elections in 1994, there was another impressive election, which followed a 15-year civil war. The peace process in Mozambique decriminalised Renamo, a guerrilla opposition aided and advised by the apartheid regime, whose practices included the recruitment of child soldiers and the mutilation of civilians. A retribution process in Mozambique would have meant no settlement at all: Renamo’s commanders and figureheads were brought into the political process and invited to run in national and local elections. The ‘broad base’ deal in Uganda, the South African transition and the postwar resolution in Mozambique were all achieved before the ICC came into existence.

Nuremberg’s epic dispensation of victors’ justice, with its uncompromising findings of guilt or innocence, is not a good model in the context of civil wars where victims and perpetrators often trade places in unpredictable rounds of violence. No one is wholly innocent and no one wholly guilty: each side has a narrative of victimhood. Like victors’ justice, victims’ justice demonises the enemy – quite likely the close neighbour – and proscribes any role for this outcast in a post-conflict society. The logic of Nuremberg – and by extension of the ICC – tends to drive parties in a civil war away from inclusive solutions towards segregation and dismemberment: military victory and the formal separation of yesterday’s perpetrators and victims into rival political communities, distinguished by new boundaries if necessary.

Human rights may be universal, but human wrongs are specific. To think deeply about human wrongs is to wrestle with the problems that give rise to acts of extreme violence, which in turn means that victim narratives must be circumscribed within a ‘survivor narrative’, less fixated on perpetrators and particular atrocities such as Boipatong or Srebrenica, and more alert to continuous cycles of violence from which communities can eventually emerge. For this to happen there can be no permanent assignation of a victim identity or a perpetrator identity.

The South African transition began as a pragmatic search for a second-best solution: a way out of a cul-de-sac where military victory had evaded both sides, and criminal trials were out of the question. Most colonised societies experienced one or another form of civil conflict as they divided on the question of who was complicit in colonial rule and who was not, and continue to divide on who does or does not belong to the nation, and qualifies for citizenship. Like the TRC, Codesa was scarcely a radical project for social justice. But it turned its back on revenge and gave the living a second chance.

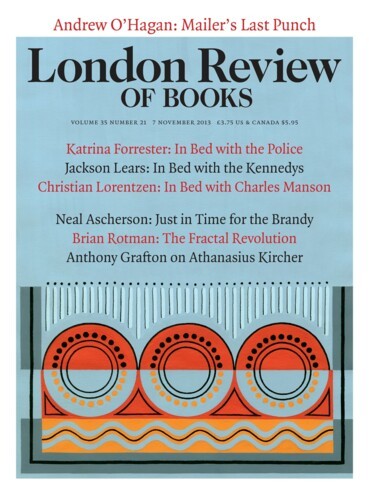

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.