Tate Modern’s retrospective of the Brazilian artist Mira Schendel – born Myrrha Dagmar Dub in 1919 in Zurich, brought up in Italy, uprooted by war to Yugoslavia, and from there to Brazil in 1949 – is moving, difficult, full of strange writing and immediate visual pleasure.* Schendel was an intellectual, feeding on Wittgenstein and Cardinal Newman (her two incompatible heroes), as well as a constant innovator in formal terms. But she was also an intellectual who thought visually: or rather, she seems consciously to have set herself the problem of giving visual expression to the extremes of clarity and opacity that thought can reach.

The Schendel show is part of a wider shift of focus at Tate Modern in the past year or so: its one-person exhibitions have stretched to include artists who are essentially new to London’s museums, or whom YBA London has for the most part forgotten. (Schendel’s only solo show in this country was in 1966.) The 279 works at Bankside are the most complete representation of the artist ever held anywhere. The galleries are full. The mostly small objects they contain are subtle, and often elusive; they generate shadows while giving off light. And when a room is turned over to a single installation – Still Waves of Probability (1969) is made of countless hanging nylon threads – the space itself softens as its edges fade away. An acrylic panel citing two verses from 1 Kings 19 hangs on the wall. The verses tell of Elijah looking for God in wind, earthquake and fire, but only finding his ‘still small voice’ in their silent aftermath.

Perhaps one way to prepare to see Schendel is to imagine an artist – one fully in tune with the ‘experimental’ 1960s, but with her own distance, living in São Paulo, from the Europe she had left – in love with philosophy and linguistics, and therefore above all determined to make pictures in which language would appear before the viewer in all its strange physicality. In the 1950s and 1960s there were maybe three dozen such artists on three continents, and from the evidence of the Tate exhibition, Schendel was the most inventive of the lot. Her skills lay first in her expansive approach to visual media. As an artist, she was self-taught, and for a while earned a living in graphic design. Books as things were part of her life (her husband, Knut Schendel, owned a bookstore at the centre of São Paulo culture) and she retained an apparently inexhaustible passion for the graphic possibilities that books and notebooks, as well as drawings, paintings, sculpture and installations, can convey. Over the years she used oil, acrylic, watercolour, tempera, gouache, gesso, oilstick, collage, canvas, plywood, rice paper, acrylic panels, nylon filaments, ink, typewriter ink (plus the typewriter to apply it), monotype, transfer lettering – and doubtless a few more media I failed to spot. And paired with this was her love of ideas. She read widely in both Eastern and Western philosophy, had many friends who were philosophers, and was the daughter of a German-speaking Czech Jew and an Italian-German mother who was also Jewish but had her daughter baptised in the Catholic Church. Schendel’s middle-class life in Europe came to an end in 1938 when her Jewish background meant that she could no longer pursue philosophy at the university; after a shadowy decade as a displaced person in Europe, she found refuge in Brazil, added Portuguese to her native German and Italian (she also read English) and remained there, with occasional visits to Europe to stage several significant exhibitions, for the rest of her life. She died in 1988, aged 69.

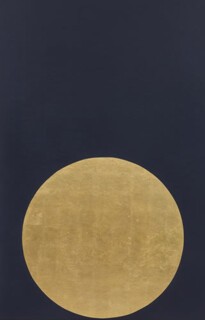

There is nothing provincial about this background. Like the United States, Brazil was an ideal place to assimilate and transform the achievements of abstraction, and the sheer substance of Schendel’s manipulation of the ruling geometries of that inheritance – the alternately urban and domestic flavour she gives them – shows how quickly she did so. Her abstraction is laconic, yet also solid. Its mostly grey and black geometries summon a world made up of fundamental components: earth and sky, light and dark, here and there. Eventually, suggestions of cities and buildings will emerge. Such effects are always intensely dynamic – I unexpectedly found myself thinking of God separating light from darkness – yet their world is oddly placeless too: post-Edenic, post-lapsarian, expecting a future which harbours few hopes.

For Schendel, the hope of the future lay in a world of words. By the mid-1960s she was again working graphically, using monotype to counter-proof text-based drawings on ultra-thin rice paper, then sandwiching them in acrylic panels mounted a few centimetres away from the wall. As a result, each sheet comes across as both image and text – or better said, as a graphically dense surface of scattered words, some fully legible, others blotted and nearly obscured. Schendel produced one such series in response to a landmark 1955-56 composition by Stockhausen, Songof the Youths (the ‘first masterpiece of electronic music’, as it is usually described), which combined electronically generated sound with recorded fragments of the human voice. By 1962 it was available on vinyl from Deutsche Grammophon. Schendel listened to its haunting palimpsest in her São Paulo studio and derived from it a set of key words, a polyglot chant of a kind, each rendered in a scrawling script that varies wildly in clarity and style. These drawings seem graphic in a whole new way: they want to make themselves heard. Fire, for example, becomes ‘FEUER fuoco fire FEU feuer FUOCO’, the simple repetition insisting on the subject of Stockhausen’s composition, God’s deliverance of three devout young Jews from incineration in Nebuchadnezzar’s furnace. Freud analyses a dream in which a mourning father imagines his dead son asking him: ‘Father, can’t you see I’m burning?’ Schendel’s work, when joined with Stockhausen’s, brought the unbearable question into postwar art.

In the mid-1960s Schendel began to worry multiple sheets of rice paper into thickly compressed ropes or ribbons, then knotted and knitted them into loose chains or fabrics which, when heaped on the floor or suspended, look like improvised nets. A few years later, in her Bowery loft, Eva Hesse would work with net bags, and then, a bit later still, with great skeins of knotted rope. And when Hesse was hanging blank panels of translucent latex under the title Aught, with its echoes of ‘ought’ and ‘naught’, Schendel was aligning drooping clusters of the same soft paper she loved to work with, forming rows her young daughter Ada named Trenzinhos, ‘little trains’. The title stuck, as did Droguinhas, ‘little nothings’, Ada’s pet name for her mother’s knotted nets. Schendel’s ‘little’ works convey a seductively delicate physicality, yet the unexpected presence she teases out of her infra-thin paper combines with its built-in blankness and absence in a breathtaking way. On these trains, no one rides, and in these nets, no one is caught – except the viewer, and inevitably, the artist herself. ‘Little nothings’ perhaps, but nonetheless capable of summoning the enormous nothing that haunted postwar experience, its wholesale destruction of life.

Schendel’s aim, however, was to take the viewer beyond nothingness. The Tate show argues that she reached that goal. The route lay through the most ambitious of her installations, which she conceived for the Brazilian pavilion at the 1968 Venice Biennale. It brought together 12 Graphic Objects (Objetos gráficos), hanging plexiglass ‘pictures’, each no more than a metre square, with two layers sandwiching a sheet of rice paper overwritten with an array of handwritten letters and letter-like signs. Transfer lettering crops up between them, its crisp san-serif speaking to its characteristic use by architects and graphic designers, and standing out amid the signs and shadows collecting in drifts and swarms.

These panels are meant to be seen in daylight, as the Tate installation marvellously allows. The result is an experience of reading their non-messages through and within each other, while perceiving each floating presence as a separable thing. The effect summons shadow upon shadow, while outside is light. In her diary, Schendel described her intention as ‘an attempt to show that the back of transparency lies in front of you, and that “the other world” is this one.’ A typically quiet and enormous ambition, which time and again, the work fulfils.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.