Say this city has ten million souls,

Some are living in mansions, some are living in holes:

Yet there’s no place for us, my dear, yet there’s no place for us.‘Refugee Blues’, W.H. Auden

Marseille is an old-fashioned town. ‘You still have a queen,’ the lady checking museum tickets remarked. ‘So why don’t you cut her throat? Kings and queens are pointless, cost a fortune.’ Red Republicanism, 1793 brand, is not extinct here.

This year, Marseille is a European Capital of Culture, which means it must make a show of cherishing its past. The Ici-Même (‘on this very spot’) exhibition commemorates the city’s experience of war and occupation. Most of it focuses on heroic resistance and liberation. But there’s also a section which remembers the thousands of refugees who fled here in 1940 before the advancing Nazis, frantic to find an exit visa and a ship. The staff of the exhibition, held at the municipal archives, hadn’t heard of Auden or his song. What they had repeatedly heard, and were getting sick of, was a smart line thought up by somebody in the city government: ‘2013 is not the first year that Marseille was European Capital of Culture. The first time was in 1940.’

The refugees often came with their families, often penniless and exhausted, often with the wrong papers or none. Among the crowds jostling for a room in a cheap hotel or a place in a consulate queue were constellations of German, Austrian and Eastern European anti-fascist celebrities: Heinrich and Golo Mann, Hannah Arendt, Anna Seghers, Simone Weil, Arthur Koestler, Victor Serge, Walter Benjamin, Franz Werfel and his wife Alma Mahler, Lion Feuchtwanger, Konrad Heiden (Hitler’s first truthful biographer), Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, Moïse Kisling, the young Claude Lévi-Strauss … A band of surrealists led by Max Ernst (Tristan Tzara, Wifredo Lam, André Breton among them) hid in the spooky Villa Air-Bel in the city’s outskirts.

Marseille was in the non-occupied zone of France. But Article 19 of the armistice agreement with Germany obliged the Vichy government to ‘surrender on demand’ German citizens who might be wanted by the conquerors. Everyone knew that the Germans would invade the southern zone too; it was just a question of when. But there were fewer and fewer ships leaving the port, and – as the German intellectuals recognised – the bureaucracy of departure was Kafkan. To have a residence permit in Marseille, you had to prove you didn’t mean to stay. But to leave you needed an exit visa, which required a foreign entry visa, transit visas from other countries and a steamer ticket. By the time your papers were ready, the steamer might have sailed or the residence permit and/or the foreign and transit visas might have run out. Or you might be pulled off the boat at the last moment because you had no French certificate of release from a camp for ‘enemy aliens’.

The consul banged the table and said:

‘If you’ve got no passport you’re officially dead’:

But we are still alive, my dear, but we are still alive.

The refugees lived in fear and poverty. A fog of rumour – a ship departing, or a wave of arrests – hung over the crowded cafés at the foot of the Canebière boulevard. The refugees sipped ersatz coffee, nibbled unfamiliar pizza bought with ration cards and stared at the empty blue Mediterranean. A bitterly cold winter set in. Many of the fugitives were Jewish, and they had a good idea of what could happen to them. There were suicides. German officers were seen entering the prefecture. People began to vanish.

The two leaders of the German Social Democratic Party, Rudolf Breitscheid and Rudolf Hilferding, refused to panic. They turned down a chance to escape illegally from France; instead, they sat on in their favourite café on the boulevard d’Athènes assuring everyone that Pétain would respect their exile status. One day they disappeared. Hilferding was found hanged in Paris; Breitscheid was murdered in Buchenwald.

All this seems remote in the hot summer, as Marseille enjoys being Capital of Culture. The natives don’t do nostalgia. The famous émigré cafes like the Brûleur de Loups and the Mont Ventoux vanished long ago, and the Villa Air-Bel has been knocked down. Instead, there is dazzling new architecture. The old Fort St-Jean was once a barracks and jail where Koestler, disguised as a Foreign Legionnaire, found British soldiers who had escaped Dunkirk (‘I haven’t tasted decent soup since I’ve been in this bloody country!’). Now, scoured and signposted for heritage, it connects by a bridge to Rudy Ricciotti’s MuCEM (Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée), an enormous cube clad in ceramic jigsaw pieces which evoke the glittering currents in the sea below.

MuCEM’s exhibitions, trying to evoke the contradictions of the Mediterranean, are wild, erratic and never dull. There’s an anti-clerical spirit around, which suits the city’s history – in one place, a screen on which three terrific females, Jewish, Muslim and Christian, say what they think about each monotheistic religion’s attitude to women. But MuCEM’s image of Marseille is always of a destination, a place to which the ships of immigrants and merchants are heading. That other year of culture, when the point of Marseille was to get out of it as fast as possible to almost anywhere else on earth, is not emphasised. Anna Seghers, in her masterly novel Transit, wrote: ‘Mothers who had lost their children, children who had lost their mothers. The remnants of crushed armies, escaped slaves, human hordes who had been chased from all the countries of the earth, and having at last reached the sea, boarded ships in order to discover new lands from which they would again be driven; for ever running from one death towards another.’* In Scum of the Earth, Koestler called Marseille ‘this last open port, Europe’s gaping mouth, vomiting the contents of her poisoned stomach’. The writer Hans Sahl wrote of ‘the condition of hopelessness, the waiting for ghost ships which would never put to sea, for visas which would never be delivered – the thought of being trapped here on the very fringe of Europe’.

The Ici-Même designers have laid an emigrants’ trail across Marseille, with inscriptions stencilled on the pavement where a famous café once stood or a consulate doled out visas or the Gestapo had its headquarters. Some commemorate rescuers, foreign men and women who saved lives. Gilberto Bosques, the Mexican consul, arranged the escape of many hundreds of Spanish Republicans, survivors of the International Brigades and Jewish civilians. Donald Caskie, from the Church of Scotland, was one of several rescuers who hid British soldiers and RAF crews and smuggled them over the border to Spain. And then there was Varian Fry, the young American who ran the Emergency Rescue Committee from his poky room at the Hôtel Splendide. Fry was given a list of a hundred ‘prominent intellectuals’ whom he was instructed to find and support with American money. In the event, Fry and his brave staff overstepped instructions and set about the wholesale fixing of illegal escapes, often providing the fugitives with fake passports and visas.

Some went by ship, but many went over the Pyrenees into Spain and on to neutral Lisbon, heading for the Americas. Fry’s adversaries were the Vichy authorities, who eventually expelled him in September 1941, and his own government. The US State Department was determined not to offend the Vichy regime (this was before America joined the war), and had a sullenly xenophobic, not to say anti-semitic, attitude to European refugees begging for visas.

Fry seems to have helped something like two thousand people to reach a safe country. But he was a complex, driven man and he agonised. His remit was to save an elite. What about the others? At the end of May, 1941, he wrote afterwards, ‘we found that in less than eight months over 15,000 people had come to us or written to us … We had decided that 1800 of the cases fell within the scope of our activities. In other words these 1800 were genuine cases of intellectual or political refugees with a good chance of emigrating soon.’ Counting family members, this meant about four thousand human beings. Put bleakly, he had had to turn away and abandon three-quarters of those who begged him for help: his committee back in the States had taken fright and in effect disowned his methods before Vichy took action. I think he never got over it.

Went down the harbour and stood upon the quay,

Saw the fish swimming as if they were free:

Only ten feet away, my dear, only ten feet away.

In a stanza further on, Auden’s elderly German-Jewish couple see ‘a building with a thousand floors,/A thousand windows and a thousand doors:/Not one of them was ours, my dear.’ When I saw the gigantic red hulk of the old tile-works at Les Milles, near Aix, those lines came instantly to mind. This was Vichy France’s concentration camp for foreigners. At first, while France still fought, Les Milles detained ‘enemy aliens’. That meant great and small people who had found asylum in France after fleeing from Hitler, but also oddments like a troupe of German performing dwarfs, all fervent Nazis, hauled off a ship seized by the French navy.

After the surrender in June 1940, Vichy used the place for ‘undesirables’ in transit: foreign refugees, Spanish Republicans and anyone seeking an exit visa through nearby Marseille. It was in this period, from 1940 to 1942, that Les Milles became a holding camp for Europe’s anti-fascist intellectuals – the ones who did not yet have a visa for another country. The women and children were billeted in Marseille hotels and shelters; the men were thrust into the darkness, hunger and verminous filth of this vast factory where thousands of human beings lay on bare floors. Those who had already been in Dachau or Buchenwald found it familiar, except that the French guards did not show sadism. Instead, they showed a quality which Feuchtwanger, who spent time in Les Milles, described as ‘je m’en foutisme’ – in this context, homicidal indifference. Somehow, culture survived. Max Ernst was one of those who used the ‘catacomb’ labyrinth of the tile ovens as a studio and a place to hold clandestine meetings.

As the months passed, the Vichy regime degenerated from numbskull conservatism into racist fascism. Jews, French or foreign, were excluded from normal life; and in the summer of 1942, more than two thousand Jewish would-be emigrants in Marseille and the region were rounded up and held in Les Milles. From there, sealed trains took them to Drancy, outside Paris, and then to the gas chambers of Auschwitz and Sobibór. The French authorities made sure that the children went too – more than a hundred of them from Les Milles. All this was done months before the Germans occupied the southern zone in November 1942.

Thought I heard the thunder rumbling in the sky;

It was Hitler over Europe, saying: ‘They must die’;

O we were in his mind, my dear, o we were in his mind.

Long after Fry had left, the Hôtel Splendide became a German headquarters. These days it is a bookshop, and a family of homeless Roma sleeps on its broad street-level windowsill. A photograph shows a group of SS and Gestapo officers standing in the doorway, disentangling the straps of their Leicas for a morning of cultural tourism. In January 1943, a bomb was thrown into the foyer, killing a German woman and a hotel worker. In response, the Germans dynamited the entire north side of the Old Port and drove its 15,000 inhabitants into detention camps. But the city authorities bargained desperately. If the Nazis would spare the town hall and the Maison Diamantée (a Renaissance merchant palace), they would round up the Jews and ‘undesirables’.

The deal was done. The Marseille police went into action. Something like two thousand men, women and children, half of them Jews, were deported. Most of them were murdered. Today, the Maison Diamantée stands and glows, a centrepiece of the Capital of Culture. Heritage preservation can be very expensive.

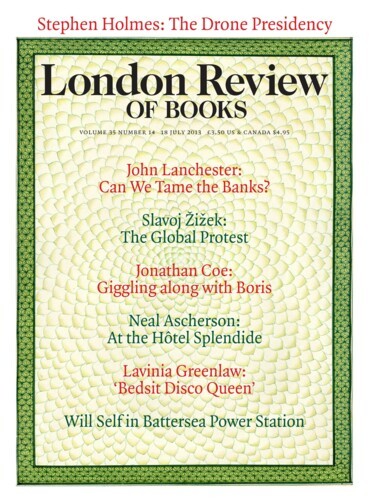

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.