In 1845 Captain Sir John Franklin led 128 men in search of the final stretch of the Northwest Passage. When they failed to return from their expedition, a number of relief parties were sent out to find them. Over the next decade, naval commanders, traders and amateur sleuths collected objects and relics from the area: signs of what may have become of the lost men. Handkerchiefs, soap, sponges, slippers, combs, forks and spoons were all brought back. One of the ships sent out after Franklin, the HMS Resolute, itself became trapped in the ice. Timbers from its hull were later retrieved and a desk was built from them; Barack Obama now sits behind it in the Oval Office. As a souvenir of another voyage, the Reverend W.H. Holman collected a narwhal tusk, which he donated to the museum in Canterbury, which made it the centrepiece of the Cabinet of Curiosities in what is now known as the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge. (The Cabinet also contains a pangolin, a glass egg filled with nuts and seeds, a little bustard, a duck-billed platypus, a bronze lizard with a man’s face and a medallion showing Strasbourg Cathedral.) The narwhal tusk, skinny, gnarled and twisted, is currently standing upright in a glass case outside the entrance to Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing, an exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate (until 15 September). The very tenuousness of its relation to Franklin’s doomed expedition is part of the point: it’s an icon that bears no visible trace of its history; it’s just a thing that was found when some other things were lost. And it looks rather fitting against the backdrop of the North Sea and the fairground rides on the beach.

The objects collected in Curiosity are – to put it mildly – varied. They range from blown-glass models of sea creatures, made by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka between the 1850s and 1890s, to a collection of agates, alabaster, quartz and jasper put together by Roger Caillois, a collaborator of Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris, to a vitrine displaying tiny artworks made from split lengths of human hair, collected by the artist Susan Hiller, to Richard Wentworth’s snapshots of traffic cones or abandoned gloves or old boots. Some of the objects are related in theme: to go with the Arctic tusk and its story of loss, there’s also a king penguin Shackleton brought back from the other pole, now stiff as a board in a box. But otherwise miscellany is the aim. The one thing they all have in common is the idea of collection itself. In Museum Section, a drawing commissioned for the show, Pablo Bronstein has made a plan of a fictional museum and filled it with the objects actually on display in Margate. Turner Contemporary is a white-walled, high-ceilinged, light-filled, standard-issue modern gallery; Bronstein’s drawing instead imagines a grand palazzo, a Villa Borghese-type museum, with many small rooms on multiple levels, a layout that’s kaleidoscopic and eccentric, a dream of a place for these objects to inhabit. If it can’t be the Villa Borghese, though, they’d all go quite nicely in Sir John Soane’s Museum, with its domes and crypt and secret corners. Even the essays in the exhibition catalogue (Hayward, £22.99) are collections of a kind: Marina Warner and Brian Dillon, the show’s curator, have both written magpie pieces that list facts about collecting and find disparate ways of talking about the idea of curiosity.

Part of the pleasure of the cabinet of curiosities is, of course, that ‘curiosity’ has two meanings: the ideal Wunderkammer is an assembly of curious things collected by curious people. And some of the freakiest things in the show represent both kinds of curiosity at once. There’s an impossible-looking series of photographs of popes and bishops looking through telescopes: it’s hard to imagine a more recherché subject for a collector. They were all found by Laurent Grasso, who trawled through the Vatican archives for any pictures of pontiffs handling astronomical instruments. There’s no clue as to what the clerics are actually doing. Studying? Posing? Disapproving? Looking for God? And then there’s Nina Katchadourian, who spent a few years photographing fellow passengers in the aeroplanes she was travelling in: intrusive, nosy, curious, she was a collector of sleeping strangers. Also on display is her series of self-portraits taken inside aeroplane lavatories, done ‘in the Flemish style’. From a distance, she indeed looks like a figure in a Flemish painting wearing headdress and ruff; up close, the headdress reveals itself to be a white vest draped over a curved cushion balanced on the artist’s head, and the ruff a series of paper tissues tucked into the neck of her top.

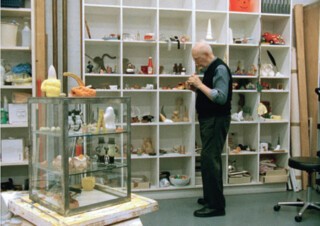

The best view of a collector interacting with his collection is Manhattan Mouse Museum, a film by Tacita Dean showing Claes Oldenburg in his studio cleaning the objects on his shelves. Oldenburg was 82 when it was shot; he wheels from item to item on his office chair, and his hands tremble slightly as he picks each thing up, dusts it with a dinky brush, then replaces it, in what looks like a long-established ritual. The objects – the tomato ketchup bottle; the toy car; the bowls; the cartoon ceramic figures – are bric-à-brac that assume a higher status through the reverence with which they are handled. The brilliance of Dean’s film is in the tight close-up on those pecking hands, the quiet shuffle of the chair, Oldenburg’s mesmerising focus on his beloved things.

There are a lot of unlovely things too. A collection of Rolodexes taken from Los Alamos contains hundreds of business cards with all the contacts you would need to help build and maintain a nuclear bomb. They were picked up by Ed Grothus, a Los Alamos lab technician who resigned in 1969, disillusioned by Vietnam, to create a salvage company and thrift store called the Los Alamos Sales Company. There are business cards belonging to John E. Drake, assistant product manager of Explosive Technology, Products Division; and Erich Muehlberger, manager of the Hyperthermal Test Facility in Santa Ana, California.

Bleak in a different way are the crime scene reconstruction models created by the Chicago heiress Frances Glessner Lee, seen here in photographs taken by Corinne May Botz. In the 1940s Lee made twenty dioramas at a scale of one inch per foot showing scenes of unexplained deaths. From a distance they look like doll’s house set-ups. But a cosy-looking kitchen scene – blue stove, freshly baked pie, ironing board with lace-trimmed mat – is disrupted by the corpse of the industrious cook and laundress lying face up on the floor, a tin of something next to her head. It’s macabre, but compelling: you find yourself scrutinising each tiny thing in the room – the cutesy reindeer-and-foliage-patterned wallpaper, the rolling pin – looking for clues. The models were composites of real cases: Lee used them in training seminars she ran at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, and the trainee detectives got ninety minutes to examine each scene. Is that long enough? We’ll never know: the solutions to the puzzles haven’t been made public. The usual line on things in museums is that paying close attention to them is proper, but one of the lessons of this curious exhibition is that sometimes the really interesting task isn’t the looking but the gathering, the organising, the cataloguing, the handling. There’s a box on display in the gallery that says it all. It contains thousands of photographic slides commissioned by the artist Katie Paterson. Every one is pure black, a photograph taken of the night sky from some point on the globe. There couldn’t be a more perfect collection.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.