Simon Starling’s film installation Phantom Ride, commissioned by Tate Britain for its vast Duveen Galleries, takes its title from a cinematic fad of the early 1900s. Cameras and cameramen were hitched to the buffers of trains, and latterly trams, and filmed the track and scenery as they hurtled along. An early phantom ride was typically a single shot, just a few minutes long, which might, if you visited Hale’s Tours of the World (established on Oxford Street in 1906), have had its speeding colonial vistas enhanced with railway whistles, hissing steam and even shaking benches. Punters craved exoticism as well as velocity, though the thrill sometimes consisted in seeing familiar spaces at speed: there were phantom rides through Ealing, Leeds and Southampton, and in 1910, A Trip on the Metropolitan Railway from Baker St to Uxbridge and Aylesbury.

Starling’s art has frequently involved the reconstruction or repurposing of ramshackle machines. In 2005 he won the Turner Prize with Shedboatshed, rebuilding a tumbledown hut from the banks of the Rhine as a small boat, rowing it to Basel and turning it back into a shed for a show at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst there. He seems to have spotted that there’s something of the railway station, or even the barrel-vaulted carriage, about the Duveen rooms, which were completed in 1937 expressly to house sculpture. Something also of the arcade or the showroom: spaces in which one can be transported while standing still. Phantom Ride, which is shown on a large screen suspended across the riverside end of the gallery, doesn’t take us outside the museum, but instead tells what Starling calls ‘a sort of ghost story’ about the objects formerly displayed there. Neatly, many of these are previous Duveen commissions.

In keeping with its cinematic ancestor, the looped film is seven minutes long; in place of late Victorian sound effects, the gallery is filled with a minatory drone that intermittently turns into mechanical whirrs and creaks. These are the exaggerated sounds of Starling’s motion-control rig, set up over six nights so that the camera could dart and swoop across the gleaming black floors, through empty arches and up towards distant cornices and discreet modern light fittings. At each turn it discovers works exhibited in the gallery over the past seventy years, and where those works are unavailable or no longer extant they’ve been simulated using CGI. The whole has the slick and sickly aspect of slightly dated Hollywood special effects, just convincing enough to make Picasso’s Charnel House or a group of mirrored cubes by Robert Morris seem not quite right.

The combination of ‘real’ footage, digital effects and a complexly motile camera makes for seductive and startling effects, as the ghosts of exhibitions and installations past appear and swiftly vanish. There’s some knowing frustration here of the filmic convention of shot/countershot. Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from ‘The Rock Drill’ turns its black visage in our direction, Darth Vader-like, before being swept away. The camera glides over the reflective surfaces of Fiona Banner’s Jaguar – a full-size fighter plane shown, upside down, in 2010 – and speeds off to light on architectural details or plumb the shadows of other rooms where other works lurk (a Henry Moore? another Epstein?). In a shot that is, cinematically speaking, pure Harry Potter, a statue of St George and dragon floats in mid-air without its plinth, then is gone in a twinkle of computer-generated lens flare.

In fact, some of the best and strangest moments in Starling’s film, ones that make subsequent strolls through the Tate displays feel vertiginous and untethered, are those where the art has momentarily faded out, and the camera is set loose to float towards the vaulted ceiling. Then the place seems properly ghostly, and so does the visitor: like De Quincey’s Piranesi, climbing ever upwards through his Prisons, ‘until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall’.

For the most part, things are more concrete, if uncanny. Perhaps it’s already clear from the works I’ve mentioned that Starling chose pieces (twenty of them) not only on grounds of their art-historical fame or their spectacular nature, but because they dealt with war and destruction. Almost all of the sculptures, paintings, photographs and films reconvened or reimagined for Phantom Ride involve images or technologies of violence. The camera swerves around Michael Sandle’s A 20th-Century Memorial: an elaborately queasy rendering in bronze and brass of a skeletal Mickey Mouse equipped with machine gun and tripod. There’s another machine gun among a cluster of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s sculptures. Patrick Keiller’s 2012 installation The Robinson Institute (which also involved the filmmaker trawling the Tate archives) supplies several apposite works, among them Leonard Rosoman’s 1942 painting Bomb Falling into Water.

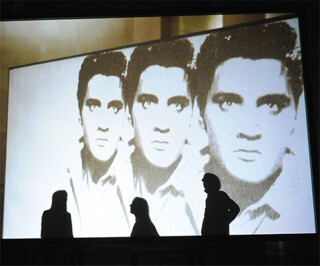

In the press release for Phantom Ride, Starling quotes Foucault’s claim that the modern museum or archive is a space that aspires to corral all times within its walls. There is certainly a sense that the film compacts moments from the Duveen Galleries’ seven decades into its seven minutes, and a recognition that a museum is also a ghost of itself, a repository for institutional memories of all its past exhibitions and displays. But the more apt reference, which Starling surely has in mind, is Paul Virilio’s work on modern warfare and the machinery of seeing. Because what Starling discovers isn’t a simple thematic concern with war and its depredations, but a fascination with the moving eye and with sightlines – and it’s that fascination that links the layout of a gallery with Mickey the machine-gunner, who trains his barrel straight at the camera, or Warhol’s Triple Elvis, who points his pistol at us three times. Phantom Ride is like a drone’s eye view of the gallery’s history. And in case we miss the point, Starling shows us a tiny balsawood model plane – part of Chris Burden’s 1999 project for the Duveen, When Robots Rule – slowly circling and then landing in a pool of light.

It’s not so obvious to what end Starling has composed this admittedly beguiling set of symmetries between the gallery, theatres of war and the historic palaces of commodities the Duveen so resembles. Of course the installation makes one think scurrilous thoughts about the management of gallery-goers’ lines of sight and modes of attention elsewhere at Tate Britain, which has recently rehung its main displays according to a more or less strict chronology. (A chronology that produces exactly the sorts of odd meeting between artists, works and media that a thematic or transhistorical hang is meant to produce.) But perhaps the more lasting effect of Phantom Ride is not in the slightly dreary realm of institutional critique, which here looks a little too much like institutional advertising, but in its melancholy imagining of institutional collapse, as Starling’s camera drifts across a CGI scene of the bomb-damaged Duveen Galleries in 1940, and asks us to picture the place in ruins, supplanted by its lubricious digital twin.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.