I am sitting at 291 in Rare Books and Music – that’s seat 291 in one of the British Library’s reading rooms. Opposite me at the same oak and green leather desk are two students, both of whom are reading books, checking their BlackBerries and looking at their Apple and Acer computers. You wonder, how much more multi can tasking get? Then there’s a phenomenon called ‘noting’, a form of anonymous flirting in the more popular reading rooms, Humanities I and II, or Hum One and Hum Two, as they’re called. You’re seen, then there’s a note on your desk, you have no idea who did the noting. Nor do the guards at each reading-room entrance who have cameras that spy on every desk, but they’re incredibly quick if you pull a pen from a pocket.

Yesterday I ran into J who was drinking coffee with her friend B; today I meet P, an American friend who has been trying to get a visa to live in London and who suggests having lunch at Chilli Cool, a Sichuan restaurant south of the Euston Road popular with Chinese students in London, many of whom arrive by cab. But I can’t because I’m already busy. Q, with whom I go to a Japanese restaurant on not-far-off Chalton St, rings to say he is with his children near where I live; I tell him I’m at the library. There are faces I recognise from dust jacket photos, but overwhelmingly I know no one at the British Library, and it’s only every now and then that it has a passing resemblance to an Eric Rohmer suburb where everyone seems to know everyone else and there’s trouble ahead because they do. It is early April, university Easter holiday time, which coincides with the writing of dissertations and exam revision: the reading rooms and the halls of the library are often full. There are 1200 seats in the reading rooms, around a thousand employees at the library, and each day there are several thousand visitors. How much noting is going on I don’t know. Several years ago, with the idea of making it more popular, the librarians dropped the membership age from 21 to 18 so that undergraduates could apply. Not that you have to be a member to use the wifi if you’re at one of the many tables and chairs that line some of the library’s thoroughfares, which are often bedlam. High-minded modernist ideas and aspirations may have driven Colin St John Wilson to design his building as he did, but it’s the unruliness of some who go there that makes it appealingly lived in.

Study describes what goes on inside, obviously – except, and equally obviously, when it doesn’t – but in its outward aspects the library is sturdiness itself, the more so when compared to the elaborate, sky-bound roof of its similarly enormous neighbour, St Pancras station. The library is surrounded by a number of large buildings, both old and new. Through the trellises on the cafeteria’s north-facing terrace is the building site of the forthcoming Francis Crick Institute, whose research laboratories will open in 2015: 1500 people are expected to work there. To the west is the Ossulston Estate, or the ‘Ring Road of the Proletariat’, as it’s also known, a Grade II listed housing project inspired by the very much larger Karl Marx-Hof in Vienna. To the east is St Pancras and the renovated King’s Cross. Sandwiched between the two stations is the campus of Central St Martins, the name given to the merger between the Central School of Arts and Crafts and St Martin’s School of Art. One of the criticisms made of the new library was that it would have no connection with the rest of the area – something you couldn’t say now. You’re surrounded by a lot of ‘highly curated distractions’, N says; she means there are numerous ways to not go to the library. You’re also surrounded by a lot of young people.

‘No bloody good’; ‘a Babylonian ziggurat seen through a funfair distorting mirror’; ‘the assembly hall of an academy for secret police’: these were a few of the drive-by appraisals of the new library when it opened, the last of them Prince Charles’s. Who knows what a secret police academy looks like, and no espionage academy I’ve heard about has two copies of Magna Carta, whose 61st clause allows for a committee of 25 barons to overrule intrusive monarchs.

There’s what you read because you need to read it; there’s what you read because you need to be distracted. This morning there’s what you read to know a bit more about your surroundings. I ordered Wilson’s The Design and Construction of the British Library. It was to be built so that it lasted at least two centuries: this was one of the broader specifications handed to Wilson after he accepted the job as the new library’s architect in 1962. Another consideration was no less temporal: ‘This job may take quite a long time to get done,’ he was told by the committee that selected him, not because the building work would take an age but because the arguing over where and how the national collection of manuscripts, books, maps, recordings etc should be housed would be protracted. Astute advice: it took as long to plan, build and complete the new BL as it did to finish Wren’s St Paul’s, and whatever you think of Wilson’s design, it’s to his credit that he finished the building and that it works as well as it does: there aren’t many people whose perseverance extends over 35 years.

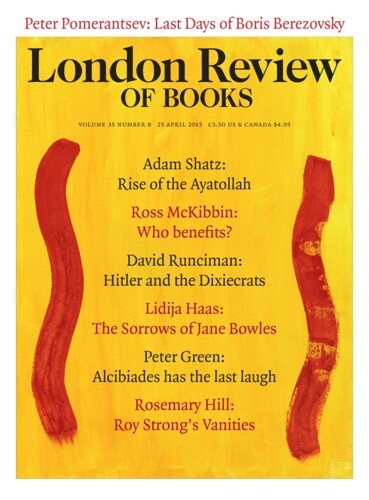

Had early plans for the library gone ahead, when the idea had been to keep it in Bloomsbury close to its original home within the British Museum, then the London Review’s offices on Little Russell Street, to the south of the BM, not to mention all of the surrounding buildings, apart from Hawksmoor’s church, St George’s, Bloomsbury, would have been demolished long before the paper was founded. As it was, the BL moved north to land owned by British Rail.

Fifty years after Wilson began his work, fifteen years after the library opened, there’s little obvious alteration to its exterior – no let-up on the relentless, red-brick redness of it all. The library looks as if it might last a lot longer than 200 years, but the clumsy courtyard might not. The crazy health and safety signs at the top of the stairs leading to the public entrance, the signs that say CAUTION STAIRS, aren’t as crazy as you might think. The surfaces of the stairs and of the uneven forecourt, built of red brick and white travertine marble, make those steps easy to miss. In the rain, the white marble becomes slick enough to trip up a sure-footed person. Wilson had high hopes for what he called a piazza. Eyeing St Pancras in the 1990s, knowing the station would eventually become the terminus for trains from Paris, Brussels and elsewhere, he thought it would become a ‘threshold to and from Europe’, a place where passengers gravitate before or after a journey. There’s nothing colder than a summerhouse in winter, and calling a forecourt a piazza doesn’t make it any warmer.

Fortress-like wouldn’t be an inaccurate way to describe the library, and it does protect a lot in special atmospheric conditions. Wilson lists some facts and figures in his appendix: the temperature of the reading room remains the same 21°C in summer and winter, and the humidity is 50 per cent, give or take five points – depending on how many people are inside. The books are stored at a constant 17°C. There are 38 lifts, 71 lavatories, and the roofs are made up of 50,000 Welsh slates.

‘I can think of no more fitting way to signal the start of the information age,’ said the chairman of the BL Board, John Ashworth, when the new library opened in 1997. I didn’t own a laptop computer in 1997, I remind myself, and Al Gore’s information superhighway was a new term, but Ashworth was far-sighted. In early April the library announced it would keep a record of all pages of websites with a ‘.uk’ suffix in their URL. As one of the librarians told Wired magazine, ‘in the four hundred years we’ve been archiving newspapers we have collected 750 million printed pages. With the digital archive, we’ll be collecting a billion web pages in a single year.’

I’ve never especially liked working in libraries, and that last detail doesn’t make this library more welcoming. H sends an email saying it’s lunchtime, and that we should meet at the stairs – by the signs that say CAUTION STAIRS. It’s warm for the first time this year; people are sitting in the piazza, which is looking very much more piazza-like, though I can’t be sure anyone has arrived hotfoot from the Eurostar. H and I decide to go to St Pancras to have lunch, and look at trains heading south.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.