Jonathan Meades, for the last thirty years Britain’s most consistently surprising and informative writer on the built environment, has finally published a book on the subject. A volume did appear in 1988 – English Extremists, written with Deyan Sudjic and Peter Cook, celebrating the postmodern architects Campbell Zogolovitch Wilson Gough – but since then his medium has been television. Meades has never been a fully paid-up architectural correspondent; he argues in Museum without Walls that taking up such a job helped destroy Ian Nairn, the pugnacious, melancholic writer and broadcaster who is his most obvious precursor. It’s telling that this book doesn’t appear courtesy of the Architectural Association or any of the other publishers you might have expected to show an interest, but as part of a ‘crowdsourced’ endeavour with dozens of benefactors chipping in to pay for publication.

The fact that Meades has been so roundly ignored by the architectural profession and its media is bad news for British architectural culture, which generally veers uninterestingly between lordly technocracy, on the one hand, and guilty talk of ‘active frontages’ and the ‘public realm’ on the other – but it’s happier for television viewers. Starting with The Victorian House in 1986, Meades’s TV is unique. The more patronising arts programmes have become, always spoken verrry slowwlly so that viewers can understand, the more densely packed with barked lists, facts and opinions on labyrinthine, tangential subject matter Meades’s programmes have been. He talks about the suburbs of Brussels, Birmingham’s road system or the churches of the 1960s as if they were the most important, intellectually intricate things around. Which, of course, they often are: what need is there, he asks, for Donald Judd when there’s the Isle of Grain? There are gleefully lowbrow jokes and visual gags too, often at Meades’s expense. Much of Museum without Walls, which is organised into sections on place, memory, blandness, ‘edgelands’ and urban regeneration, derives in one way or another from the TV programmes, but there are no photographs or screenshots. Some of the pieces look like composites, and there is a lot of repetition. No matter: it’s a joy to read.

What Meades does most often is praise things, especially things that are habitually ignored: he is surely our greatest exponent of what the Russian Formalists called ostranenie, ‘making-strange’. Architecture, as an art form, isn’t quite mundane enough to be made strange, and for that reason Meades would seldom recognise his writing as being about ‘architecture’ as such. Rather, it is about Place, somewhere architecture happens, at times in a very dramatic way, but doesn’t necessarily have the leading role. Architects take non-art, ‘the rich oddness of what we take for granted’, the mutability, detritus and accident that define truly worthwhile Place, and replace them with something static and unchangeable. However, unlike Iain Sinclair or the London ‘psychogeographers’, with their taste for pathetic fallacies and loathing for anything remotely new, Meades does not fetishise the spaces between. ‘I have to admit to a fondness for pitted former rolling stock dumped in fields and for abandoned filling stations,’ he writes. ‘But man cannot live by oxidisation alone. It’s not a question of either atmospheric scrappiness or gleaming newbuild. It’s a question of both/and. It’s a question of the quality of the atmospheric scrappiness, the quality of the newbuild.’

It seems so obvious when it’s put like this. But there’s an economic problem. There are Places – in London, Sheffield or Manchester, in recent years – where the richest of unplanned, ad hoc and ‘unsafe’ spaces have coexisted with gleaming, if variable newbuild, but it’s an evanescent possibility realised only for a moment, until the next phase of the property deal goes through. Architects aren’t good at recognising the value of these places, but that’s at least in part because it doesn’t pay to do so. And the post-1968 solution of ‘Non-Plan’ doesn’t appeal either: ‘The application of libertarian laissez-faire to the construction of new places or the alteration of old ones is grotesquely short-term.’ Place, caught between the equally hostile intentions of developers and planners, is precious and liable to sudden disappearance.

Meades is sometimes luxuriantly nostalgic, but he isn’t a sentimentalist. His taste in architects is essentially a list (Meades likes lists) of refined barbarians. The pantheon contains John Vanbrugh, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, S.S. Teulon, William Butterfield, Frederick Pilkington, Dominikus and Gottfried Böhm, Claude Parent, Rodney Gordon, Richard Rogers (in his Gothic moods), Zaha Hadid. Sometimes, as with the Communist emulator of the style of Italian Fascism Douglas Stephen, architect of a ‘Dan Dare mini-skyscraper’ in Swindon, or the South London aesthete Sextus Dyball, designer of delirious suburban villas, you might think he’s making them up. He isn’t. The North, broadly conceived, is Meades’s fixation, bar brief ventures into Spain, southern France and Argentina, and his lack of interest in the South coincides with his unabashed Eurocentrism. This can be a problem, as in ‘Mammarial’, an essay on domes, where he claims that none were built between the Hagia Sofia and the Duomo in Florence, but not when he sticks to his mission, part of which is to persuade his audience that only self-deprecation and a lack of curiosity blind them to the fact that the roofscapes and skylines of Durham and Stralsund are the equals of Venice. Some of his favourite stomping grounds are those ‘places as far south as south of the Thames which feel – and sometimes look – as though they have migrated from north of the Humber: Chatham, Gillingham, Sheerness, Dungeness, Shoreham, Portsmouth, Southampton, Bridgwater, Plymouth, Redruth, Camborne’. What he likes about them makes for another typical Meades list: ‘docks, cranes, tars, locks, heavy industrial plant, gaunt maritime buildings, a licence to distil gin (So’ton and Plymouth only), ozonic breeze, prisons, estuarine reek, gulls built by Supermarine, piercing light’.

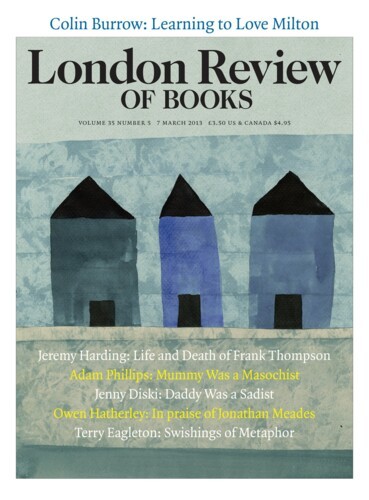

Meades’s work is so generous, so rich and so obviously contentious that to mount a critique of it seems churlish. No one else could combine all of the aesthetic and political positions he flexes so aggressively. The enemy of populism and the taste of the ‘masses’ who nonetheless shows a scrupulous respect for their intelligence; the magic-mushroom-guzzling rationalist; the passionate hater of Blair and Blairism who has a place in his heart for the Fabians and the white heat of technology; the enthusiast for Portsmouth’s Tricorn Centre (above), demolished in 2004, who dotes on Lutyens; the proud insulter of Islam who loves the multiculturalism of Birmingham; the critic of colonialism who relates the horrors of the Opium Wars and the Highland Clearances, then pauses to excoriate De Gaulle for betraying the pieds noirs; the sympathiser with the nouveaux philosophes who quotes Trotsky approvingly but pictures the ‘future mass murderer Lenin’ pottering around Letchworth. Above all, Meades is a scourge of all forms of belief, faith and ideology, of everything that he regards as childish and credulous – yet the architecture that shakes him most is created by people crazed with dogmatism and righteous fervour. Whether or not he is aware of the contradiction, it charges his prose as he grapples with his own horror and fascination: at Victoriana, at the Arts and Crafts movement, at modernism, at Stalinist architecture – most of which he loves, and most of which are based on values, theories and opinions he finds either silly or repugnant.

The Victorians, to whom Meades returns frequently, brought all the intolerance and bigotry of monotheism into architecture. Pugin started the rot, patenting

what should be acknowledged as a great English invention. He understood that his essentially philistine compatriots were loath to be appealed to on aesthetic grounds. So he devised what might be called the Pietistic Excuse or the Mask of Righteousness. It is not, he realised, sufficient to tell the English: I design this way with pointed arches and tracery because I happen to like the geometry … No, I design this way because pointed arches are holier than round ones and spires will take us closer to god than round arches and domes will.

In fact there was more happening here than this, particularly in Pugin’s successors Ruskin and Morris, who believed that Gothic architecture was closer to God because its labourers were able to express themselves while making it – a possibility that Meades does not entertain. And although he occasionally appears to wish this shift had never occurred – he identifies the metropolitan classicism of Glasgow, ‘the last British city to engage with reason’, as what everywhere else would have looked like – he is very fond of the architectural results.

It seems that there is, for Meades, something illegitimate about belief as creative inspiration, so that he is both aware of and refuses to admit the creative possibilities of the closed mind. In ‘The Absentee Landlord’, he explores postwar modernist church design, including sacred architecture designed by people who were not themselves believers, such as Le Corbusier, who undertook the commission for the chapel of Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp because he thought it would be ‘difficult’. Or, like Basil Spence, believers of the flimsiest, C of E kind. ‘Much of the ecclesiastical work of the high modern years’ – Clifton Cathedral, the work of Richard Gilbert Scott or Sam Scorer – ‘prompts awe. But that awe is more likely to be aesthetic rather than religious; it is not different to that which is incited by a grand hangar or concert hall – the potency of a building is quite distinct from its nobility (or baseness) of purpose.’

On one level this seems right, insofar as it reminds us how potent ‘base’ building can be. But Meades also argues that to be truly church-like, to keep the faithful coming, a religious building needs a ‘lack of ambiguity’ – that is, kitsch. This implies that a church cannot be both religious and ambiguous, cannot express the tensions between flesh and spirit, faith and suffering, death and transformation, and so on. Asserting that the feeling that runs down his spine in a church comes solely from spatial awe is at best an admission that he can’t share in what motivated the architect; at worst it is a get-out clause, a way of saying that ‘a structure’s purpose is ultimately provisional’ and the conversion of a church into a chain pub something only a hypocrite or a prig would worry about. Yet, strip out the superstitions and holy books and it’s clear even to Meades that some structures have an emotional ‘purpose’ that is entirely sincere and justifiable. In ‘The Absentee Landlord’ he finds this in Spence’s Mortonhall Crematorium in Edinburgh; elsewhere in Museum without Walls he finds it in Lutyens’s Somme memorial in Thiepval. Both, tellingly, are funereal and secular.

Not only religion, but belief systems of any kind – Marxism, the Whig interpretation of history, modernism, consumerism, imperialism – come in for Meades’s scorn. (Not capitalism, though: the traders of the Hanseatic League, it transpired in his programme Magnetic North, are the nearest thing he has to a political ideal.) The problem is that sometimes the greatest, most credulous, even tedious theorists and ideologues have also been the freest creators. Le Corbusier was the elemental, humanist genius of the Unité d’Habitation and the dogmatic thug of the Plan Voisin, Richard Rogers the inspired Goth of Lloyds and Antwerp and the dyslexic panjandrum of Towards an Urban Renaissance. Meades isn’t fond of architects but he is a sophisticated critic and defender of modern architecture; in one essay he recalls the disgust he felt at an RIBA conference as the ex-brutalists listened patiently to Tom Wolfe delivering an attack on modernism that was ‘remarkably flimsy, intellectually fraudulent, historically ignorant’. Yet the ‘modern movement’, as an ideology of progress and destroyer of Place, is something he unsurprisingly does not fully embrace. He is a powerful advocate for brutalism, and particularly its less-known masters such as H.T. Cadbury-Brown or Rodney Gordon, but is less keen on it as theory. Reyner Banham comes in for atypically unfair disdain (both ‘hep-cat’ and ‘after-dinner speaker’). He’s more on the mark in his account of Alison and Peter Smithson as mediocre designers and spectacular self-promoters. But what if the Smithsons’ theoretical enthusiasm for street life, mess, accident and, well, Place was an indispensable precursor of the non-Platonic modernism of Luder and Gordon’s Tricorn Centre? That said, there’s plenty of evidence that Meades’s suspicion of theorists is entirely justified. In a fascinating interview with Zaha Hadid, he is caught on the contradiction between the fluency and felicity of her design and informal conversation, and the pseudo-scientific jargon she falls into when she talks about architecture. He appears not to have noticed that the jargon comes at least in part from her partner Patrik Schumacher, author of grandiose theoretical treatises like The Autopoiesis of Architecture. A firm that was once capable of designing structures as gloriously unalike and convulsively physical as the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati and the Phaeno Science Centre in Wolfsburg now churns out remarkably homogeneous, flowing and swooping ‘Parametic’ buildings, as intangible as their computer-generated beginnings. In the interview, Meades tries to convince Hadid that her buildings are fitted scrupulously to Place, but she’s having none of it: ‘They still talk about contextual. Ha!’

The scripts for Meades’s two programmes on the architecture that accompanied 20th-century mass killing, ‘Jerry Building’ and ‘Joe Building’, are both included in Museum without Walls. Knowing how different from each other they actually looked, he doesn’t slot the built outputs of the Nazi and Soviet regimes together according to the theory of ‘totalitarianism’. Nazi architecture, as Meades sees it, is middlebrow: neoclassical or neo-vernacular, desperate not to be highbrow and cosmopolitan like modernism, but equally keen to avoid commercial kitsch. Stalinist architecture meanwhile is lowbrow, a pile-up of multiple stylistic thievings, decoration, statuary and cheap effect. He is evidently bored by the built legacy of the Third Reich, the sheer banality and mediocrity of its designers, and is keen to remind us that many New Urbanists, such as Léon Krier, the designer of Poundbury, have a sideline in special pleading for Albert Speer. The architecture is insufferable in its pretension to Gemütlichkeit and moral gravity. ‘Nothing that the supposedly decadent cities threw up has ever compared in evil to what happened in the small towns and boondocks of Germany,’ he writes. ‘The Volkisch movement politicised thatch and beams just as the Nazis’ Social Darwinism politicised biology and genetics.’ (It might be said that the Arts and Crafts movement did much the same, minus the race theory.)

When he tackles the Nazis’ relation to modernism, however, Meades is either evasive or badly informed. There was, he claims, ‘a uniquely German strain of architecture to which the entire regime was unequivocally opposed, and which it killed off. The rampant individualism of Expressionism was abhorrent to a party obsessed by aesthetic control.’ The flowing, organic forms of Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower in Potsdam were ‘what the future might have looked like had a tyranny not intervened’. The idea that the Nazis suppressed the free flowering of German Expressionist architecture is as attractive as it is untrue. The Einstein Tower, after its completion in 1921, had few successors, bar Steiner schools and Dutch council housing; the ‘rampant individualism’ of the brief Expressionist moment was finished as early as 1923, when Mendelsohn, Walter Gropius and Hans Scharoun switched overnight to a technophile language borrowed from Frank Lloyd Wright, De Stijl and Soviet Constructivism. As an avant-garde, Expressionism had been dead for a decade when the Nazis came to power; if it persisted after 1924, it did so in the neo-Hanseatic brickwork of the likes of Dominikus Böhm and Fritz Höger, both of whom became members of the Nazi Party. It was the much less individualistic language of mainstream modernism that the Nazis genuinely did cancel, or rather helped move westward.

‘Joe Building’ is a more exciting thing, the prose more charged and the arguments more complex, largely because Stalin-era Soviet architecture is closer to the sort of thing Meades likes, an impure and eye-grabbing exhibitionism rather than the tedious neo-Georgian of National Socialism. The design of something like the Moscow Metro was ‘above all else the tangible, physical expression of promise … Anticipation – that’s the thing.’ He registers the element of grotesque fantasy in the architecture of Stalinism – ‘The Soviet Union was as much founded in the work of the 19th-century poetic realists Lewis Carroll and Robert Louis Stevenson as in that of the 19th-century prosaic fantasists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ – but he would have been hard put to point to the aspects of fantasy in the works of ‘Marx, that old shaman’, the overwhelming majority of which were devoted to the analysis of capitalism rather than picturing its alternative. He doesn’t see that all the nonsense, all the bells and whistles of the Stalin style, were a way of filling, in the most unimaginative fashion, that imaginative void.

The gulf between Meades’s architectural and political knowledge opens up again when he quotes Trotsky, who ‘said that “the years 1928-31 represented the bureaucracy’s attempt to adapt itself to the proletariat.”’ ‘Put more bluntly,’ Meades glosses,

Stalin’s cultural – and architectural – programme was the search for an idiom which appeals to idiots and illiterates, an idiom which is impervious to interpretation, which can be taken only one way … Such a building offers no possibility of an alternative to its unequivocal message which, like a church’s, is an exhortation to credulous obedience and dependence.

That’s Meades at his worst, indulging in an hauteur towards believers, commies, proles and peasants worthy of a lesser, more incurious intellect. It’s also inaccurate. He has kind words for the modernist Soviet architecture that preceded the full Stalin style, but his periodisation doesn’t work. The ‘cultural revolution’ of the 1928-31 period, to which Trotsky was referring, was ranged against the church, underdevelopment, national heritage and so forth. Modern architecture was a prominent part of this: that’s why German modernist architects like Ernst May were hired to design it. Many of the posters of the time exhort peasants to flock to collective farms that look not unlike Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. The move towards the freakish fantasies and historical references of high Stalinism came later, along with the Great Retreat of the mid-1930s, by which time forced collectivisation had already caused the deaths of millions.

This isn’t (just) pedantry. Meades is sometimes strangely reluctant to admit that the architecture he (unambiguously) likes – here, Soviet modernism – might have accompanied something appalling. But if it’s all just provisional, why bother? As for the rest of that passage, there’s little ‘unequivocal’ or ‘impervious to interpretation’ about Stalinist architecture. What’s unequivocal about a building like Moscow State University, a structure built at the height of the Cold War that resembles nothing so much as the hotels and office blocks of New York in the first decades of the 20th century, supplemented with motifs that borrow from Michelangelo, interwar jazz-modern, Byzantium and a William Randolph Hearst version of Gothic? These buildings were intended to be interpreted only one way, for sure, but one reason Stalinism was so frightening was the disparity between the absurdity one was supposed to believe and the contrary evidence of one’s eyes. They’re exceptionally dishonest works of architecture – Meades has that right – and the script remains a delirious, horrified trawl round Moscow, Magnitogorsk, Volgograd, thrown out with great rapidity, brilliant observation and hectoring generalisation. It made great television, but not very good history.

Meades is better when he feels able to express how torn he is, how he is pulled this way and that. This comes most of all in the dozen or so pieces that touch on the matter of English anti-urbanism and its belated, abortive redress through the ‘Urban Renaissance’ of the Blair-Brown years. It is his view that English suburbia and exurbia are principally the fault of Lutyens. ‘Utopia is boring,’ Meades gruffly insists, but he has a lot to say about it. The first utopian colonies shared in the aesthetic of their day: New Lanark looked like a collection of workhouses; Saltaire a dense, treeless grid of a milltown. But then in the 1880s we have Bedford Park, followed by Port Sunlight and Bourneville, and the industrial model village really thinks it is a village and designs itself accordingly: ‘Never was Never Never Land more persuasively realised than by the rurally fixated, childlike Luddite of the Arts and Crafts,’ Meades writes. Outside England, the designers and planners never believed their own bullshit: Sokol in Moscow or Elisabethville in Paris are consciously a fantasy – they are in on the joke. Letchworth Garden City, as its po-faced name implies, was not. But, again, it seems that credulity was married to extreme talent. No generation of English architects was so abundantly talented, Meades claims, as that of Parker and Unwin, Ashbee and Voysey and of course Lutyens himself, ‘who designed 300 houses – and 400 of them are in metropolitan Surrey’ (a joke so accurate Meades makes it twice). He acknowledges that his first, epiphanic experience of ‘architecture’ was gazing at Lutyens’s Marsh Court on the edge of the New Forest, and sternly admonishes the Smithsons for their impudence in claiming that Lutyens had ‘perverted the course of English architecture’. But this doesn’t stop him arguing that Lutyens and his generation did pervert the course of English urbanism.

The Garden City designers thought they were creating self-contained communities, not suburbs or satellites. Meades doesn’t dislike suburbs as such, only those that look out rather than in, that convince themselves they are not suburbs. He picks as a counter-example not, as Banham might have done, the modernist garden suburbs of interwar Berlin, but the burbs of Brussels. Here tight plots, a lack of front gardens, high building, stylistic eclecticism and a culture of architectural litigation led to ‘furious invention’ as the peripheral norm. They are suburban with the stress on the last two syllables. The garden suburbs were a reaction not to the real horrors of the city, but ‘to a gamut of problems that no longer existed … the migration from cities was undertaken by fugitives not from present insalubriousness but from past fear, by refugees from an urban myth of malevolent miasma – which was more potent than the evidence witnessed by their eyes, their nose, their skin.’ This may well have been true of Letchworth, Welwyn, Hampstead Garden Suburb and the ribbons of the 1920s, but it’s of doubtful relevance for those who left Miles Platting for Wythenshawe, Shoreditch for Becontree. It’s not wholly convincing as a portrait of the 1910s, but as an analysis of the last forty years it’s probably much more accurate. He also notes that ‘the country is now the free-for-all toxic playground that cities once were,’ with a hysterical list ranging from ‘agrichemicals, organophosphates, polluted rivers, filthy fertilisers, diseased cattle, ailing sheep, poison fowl’ to

the aesthetic bereavement of agricultural buildings, the parochial xenophobia, the chippy animosity of the natives, the inbreeding, the two-headedness, the penchant for domestic crimes, the sententious drivel that is dignified as folk wisdom … It is not for the sake of preserving all this that we should resist plans to build four and a half million homes on fields during the next decade or so. It is for the sake of the people who are supposed to be in need of homes.

Yes, yes and yes. But where else is it to happen if not on the ‘wasteland’ and ‘brownfield’ (both terms he rightly disdains), the precious unplanned enclaves of Place, in the inner city?

The earlier essays here hail a return to the city. ‘What is disparaged as gentrification has been wholly beneficial because it has meant that those with the wherewithal to have some say in the city are minded to do so because they actually inhabit it – it is no longer a workplace they merely squat in by day.’ This sounds like common sense, but ‘those with the wherewithal to have some say’ is a euphemism, and the process can easily accelerate until it has priced out those who had remained in the inner city, those without that ‘wherewithal’. Meades quickly realises this. Museum without Walls has an entire section, ‘Vertical Sausaging Matrixes – Axialise an Iconic Art Hub’ on the practice and cant of regeneration, and Meades has fun with its lobotomised verbiage. All those buildings housing ‘the new, accessibly accessible, fun-style fun-arts which beacon integrated modernising lighthouse revitalisation for everyone … Everyone can inclusivise re-energising … Culture will springboard you into the happiness community.’ Most of this is taken from ‘On the Brandwagon’ (2008), which was possibly the first serious critique of the logic and aesthetics of Blairbuilding: ‘Block upon block of “luxury” flats which pleaded to be liked – in the early, needy manner of the Christian Bomber Blair. Block upon block … decorated with strips of oiled wood, terracotta-coloured tiles, translucent bricks, riveted corten, titanium scales, random fenestration.’ Devoid of its own ideas, this ‘ghost-modernism’ plundered the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, but drew the line at brutalism, which it replaced, reclad or had demolished. The social consequences of this are dire. The gradual expulsion of the poor from city centres means that there will be ‘no riots within the ringroad’. The inner-city riots of 2011 were surely at least in part a pre-emptive reaction to this imminent prospect.

In regenerated London, Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester, Meades gets what he asks for: cities that are dense, urban, bourgeois. Unlike most of his generation he does not shrink from the results. These new skylines are ‘both exhilarating and profoundly disturbing’. The later scripts and texts here take on a newly apocalyptic tone, as if the reign of that ‘grinning, Tartuffish war criminal’ has managed to make a righteous prophet, a seething extremist, out of a rationalist aesthete. In ‘On the Brandwagon’ and ‘Isle of Rust’, a superb meditation on the island of Lewis and Harris, he dreams of violent ends and imminent disaster. Lewis and Harris becomes a terrifying disasterscape littered with tight-arsed Presbyterian churches, burnt-out cars and industrial kipple, whose inhabitants manage to live what may prove to be a typical 21st-century life, connected to the world by mobile, satellite and internet, utterly uninterested in the collapsing landscape outside their door. Place will die in this ‘wi-fi wilderness’. A century hence, the machinery littering the Hebrides will ‘be discovered in a state of at least partial preservation and revered as sacred objects from a distant, pre-apocalyptic age – a paradisiac age which ended with a bleat and a rusted carburettor’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.