The scandals that have engulfed News International over the past year have given us many memorable moments, but Rupert and James Murdoch’s appearance before the Culture, Media and Sport Committee of the House of Commons last July is first among them. While James cut a predictably bitter figure, his octogenarian father could hardly have seemed less like his ruthless public persona. The Dirty Digger had become the Wizard of Oz: an old huckster, accustomed to menacing the world from behind a corporate curtain, his frailty suddenly apparent. Assailed by a protester with a foam pie, Rupert had to be protected by his much younger wife. Interrupting James’s own strangulated apology with a paternal squeeze of the arm, he wanted one statement on the record from the outset. ‘This,’ he proclaimed, ‘is the most humble day of my life.’

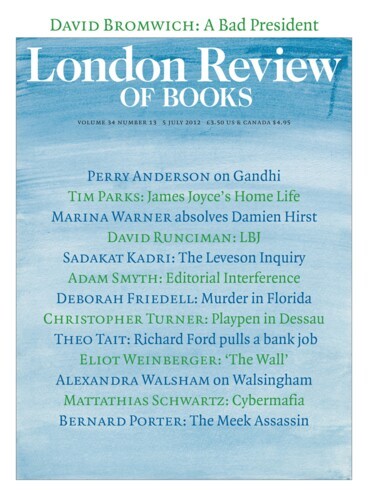

As the American satirist Jon Stewart observed, Murdoch wasn’t so humbled that he was willing to wait his turn to speak. But his very presence in Portcullis House represented an extraordinary turnaround. After dominating British journalism for four decades, he and his putative heir were having to account for their actions for the first time. The various misdemeanours of which News International is suspected have so far given rise to 12 inquiries, and the best known of them – Lord Leveson’s investigation into the ‘culture, practices and ethics of the press’ – is exposing the company to unprecedented scrutiny. Scores of people involved in or affected by its activities have trooped through the Royal Courts of Justice over the last eight months, and the spotlight has swung from intrusive journalism to News International’s influence on the British establishment. Senior politicians and police officers have anxiously played down their once prized contacts with the company, and the whiff of corruption has grown pungent.

The scandal has moved so quickly that it’s already hard to remember how it started. Dial M for Murdoch is an invaluable account of its evolution, told by Martin Hickman of the Independent, and the MP Tom Watson. Watson has been particularly close to events. In September 2006, he spearheaded opposition within the Labour Party to Tony Blair’s refusal to schedule his departure from office. Since Blair enjoyed Rupert Murdoch’s solid support, that was enough to set News International on Watson’s scent. A campaign of personal vilification followed, but Watson was undaunted. He joined the Culture, Media and Sport Committee and fought back. Dial M for Murdoch tells the story as he wants it to be remembered.

The Hitchcockian title promises a suspense that the book’s already familiar trajectory doesn’t really allow, despite the authors’ attempt to heighten the melodrama by noirishly referring to themselves in the third person. Any semblance of neutrality disappears whenever Watson encounters someone less single-mindedly opposed to News International than he is – and the class of supposed lickspittles extends from his colleagues on the Culture Committee to the BBC business editor Robert Peston and the Director of Public Prosecutions. A polemic can hardly be faulted for being quick to judge, but there is an important issue here. Although it’s easy to look on News International’s predicament with some satisfaction, we shouldn’t forget that intrusiveness is a requirement of good journalism. It was muckrakers at the Guardian and New York Times who uncovered the phone-hacking story in the first place; the News of the World, less than a year before it closed, won plaudits for a sting that exposed corruption in the Pakistan cricket team. Dial M for Murdoch abstractly recognises the value of a free press, but it laments failures to criminalise bad reporting practices without ever properly acknowledging that any restrictions of press freedom should themselves be presumptively suspect.

It all began prosaically enough, with the News of the World’s revelation on 6 November 2005 that Prince William had strained his knee. Its source – William’s voicemail – didn’t make the scoop much more remarkable; British redtops had been listening in to royal phone calls for more than ten years, and earlier tap-and-tell stories such as Squidgygate and Camillagate had caused little fuss. But this time royal courtiers decided they’d had enough, mindful of security four months after the 7 July bombings, and asked the Met’s Anti-Terrorist Branch to investigate. Clive Goodman, the News of the World’s royal editor, was charged along with a private investigator called Glenn Mulcaire with violations of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000. After pleading guilty, both men received short prison sentences in January 2007.

That might easily have been the end of the matter. A number of high-ranking officers in the Met had personal and financial links with News International and, coincidentally or not, Scotland Yard wasn’t keen to make further inquiries. Although Mulcaire had been arrested in possession of notes containing the personal details of thousands of people, the police secretly asked the CPS ‘whether the case … could be ring-fenced to ensure that extraneous matters will not be dragged into the prosecution arena’. Prosecutors obliged, making possible the falsehood, first uttered by the News of the World editor, Colin Myler, on 22 February 2007, that Clive Goodman was ‘a rogue exception’ and his crime ‘an exceptionally unhappy event’ in the paper’s history. David Cameron then satisfied himself that Myler’s predecessor, Andy Coulson (who had resigned following Goodman’s conviction), was fit to manage his relations with the press.

The appointment of Coulson, made in May 2007 on the recommendation of the shadow chancellor, George Osborne, soon proved its political worth. News International’s tabloids switched their support from Labour to the Conservatives; and senior Conservatives and Scotland Yard officials managed to stonewall tenacious efforts by Watson, his fellow Labour MP Chris Bryant and the Guardian reporter Nick Davies to show that Mulcaire and Goodman were fall-guys. The Press Complaints Commission meanwhile proved it was dysfunctional by devoting an entire report in November 2009 to a sardonic dismissal of Davies’s painstaking investigation. In desperation, the Guardian turned to the New York Times for help, and the smouldering story finally caught alight. New evidence of misconduct at the News of the World caused Andy Coulson to resign from Number Ten in January 2011, and a restructured police operation found that hacking at the paper had been rife. Reporters hadn’t just listened to the voicemails of countless celebrities and politicians; they had monitored individuals solely because of their proximity to tragedy: the father of a man killed in the 7 July bombings, for example, and the parents of several abused and murdered children. They had also directly targeted at least one dead girl: 13-year-old Milly Dowler. Public disgust peaked when the Guardian reported that journalists had deleted messages from her phone to free up space for new ones. That report was incorrect: although voicemails had been deleted, giving Milly’s parents false hope that she was still alive, they had been deleted automatically. But the damage was done. As advertising haemorrhaged from the News of the World, Rupert Murdoch flew to London to express his personal regret. In the hope of protecting News International’s brand, he closed the 168-year-old newspaper.

It didn’t work. Ed Miliband became the first British political leader for two decades publicly to criticise Murdoch, while the parent company of News International – News Corp – abandoned a high-profile campaign to take control of the BSkyB satellite channel. Apologies, financial settlements, resignations and more arrests followed, and Murdoch’s longstanding hope of establishing a dynasty suffered a major setback when, in April 2012, James stood down as chairman of BSkyB.

According to some people, like the secretary of state for education, Michael Gove, the Sun’s former editor Kelvin MacKenzie and its current associate editor Trevor Kavanagh, one of the unfortunate victims of the phone-hacking scandal is News International itself. The company is being pilloried for practices that were ubiquitous, they claim, by persecutors who give the previous Labour government a free pass. The argument, tendentious though it is, has some force. Skulduggery and subterfuge were never a Wapping monopoly, and it could be argued that some of the intimacies that pull David Cameron into the frame – the text messages he exchanged with Rebekah Brooks, for instance – pale in comparison with Tony Blair’s decision to talk to Murdoch three times shortly before the invasion of Iraq.

Dial M for Murdoch glosses over aspects of Labour Party toadying that it would have done well to discuss – most notably, Gordon Brown’s contorted attempts to ingratiate himself with Murdoch – but it does convincingly suggest that News International had no rival when it came to pushing around the weak and cosying up to the strong. The company’s executives and editors created a corporate climate in which the commission of burglary and blackmail by freelance investigators was all but normalised. At the News of the World specifically, it was not only snoops such as Glenn Mulcaire who were entrusted with journalistic functions; the paper employed at least one convict who was under suspicion of murder. Influential policemen and politicians were given lucrative contracts to write tedious newspaper columns; police officers were paid cash to reveal details of investigations; and malpractice complaints were systematically silenced by threats and secret pay-offs. As their actions seemed likely to be discovered, the company set about destroying computer hard drives and deleting emails by the million. Watson and Hickman also survey the roles played by individuals in all this: they do particularly well in tracing the complex evolution of James Murdoch’s many defences of his own behaviour. Given the large number of criminal trials in the offing, it would be injudicious to speculate about who knew what when, but Dial M for Murdoch makes it clear that lots of people knew a great deal, and knew it from early on. Anyone who claims otherwise is unfamiliar with the way that businesses work, or a liar.

Short shrift should also be given to another aspect of the right-wing whispering campaign. As the focus of Leveson’s inquiry has shifted from specific acts of media intrusiveness to the bigger political picture, critics have started to claim that Leveson is losing sight of his mission. The Daily Mail humourist Quentin Letts, for example, wrote after the ‘interrogation’ of the culture secretary, Jeremy Hunt, that the proceedings resembled ‘a Guardian-sponsored prosecution of the Cameron government’. In so far as he wasn’t just being funny, he was wrong. Leveson is obliged to probe politicians’ contacts with News International because influence-peddling is central to the story he must tell. And though the tribunal’s laconic lead counsel, Robert Jay QC, does indeed ask a lot of questions, that is because it’s his job to do so. It does not mean that Leveson will be determining anyone’s criminal liabilities; as he has already explained, it would be unlawful for him even to express opinions in that regard.

Yet the apologists for Conservative and News International interests touch on a serious issue. What is the fundamental purpose of Leveson’s investigation? Dial M for Murdoch isn’t clear on this. Several witnesses to the inquiry have expressed ideas about what Leveson should propose, but most of them are either prosaic (beefed-up rights of reply) or truistic (an end to unreasonable press excesses). The more ambitious notions, like Ed Miliband’s suggestion that media organisations be disqualified from owning more than 30 per cent of British newspapers, are beyond anything that Leveson could plausibly recommend.

Leveson himself seems minded to propose increasing criminal sanctions – raising fines for unauthorised data leaks, for example – and he will probably suggest clarifications of the many existing prohibitions on hacking, tapping, blagging and spoofing. Almost everyone seems to agree that the Press Complaints Commission has shown itself to be an impotent wreck, and he has strongly indicated that he favours creating a new complaints procedure that is neither statutory nor media-controlled, but based on independent scrutineers such as readers’ editors or ombudsmen.

An overhaul along those lines would doubtless do some good. Prosecutors spent years mistakenly asserting that voicemail hacking was illegal only if the intercepted messages had not yet been heard by the rightful recipient, and an end to confusions of this kind might improve law enforcement. But the focus on rights of reply risks perpetuating the problem that brought Leveson’s inquiry into being. There have been five other investigations into the press and privacy since the Second World War, and the most recent – the Calcutt Inquiry of 1990 – advised Parliament to give Britain’s press one last 18-month chance to prove the efficacy of self-regulation. The outcome was the ill-starred PCC, and two decades of non-regulation. If Leveson is to have a more substantial legacy, his report must engage with two issues in particular: the circumstances in which someone can sue for a violation of privacy; and how to measure the public’s interest in disclosure, in both civil and criminal cases.

Privacy can be violated not just by the publication of personal information, but also by false portrayals, the appropriation of a name or likeness, and physical intrusion into personal space. Individuals are sometimes inclined towards solitude, sometimes towards gregariousness. Someone who expects anonymity while looking at online pornography might also wish to share their sexual fantasies on a blog; social networks like Facebook depend on their users being willing to abandon traditional concepts of discretion. Reality shows have further blurred the lines, with televisual displays of intimacy becoming so unremarkable that MTV recently commissioned a programme called ‘Losing It’ – which planned to follow virgins down the path towards sexual experience. However, ‘Losing It’ was cancelled following protests – demonstrating that some distinctions between the personal and public spheres remain. At one level, that was why the News of the World’s interception of Milly Dowler’s voicemails met with such revulsion. A concern with human dignity seems somehow to require that such intrusions be prevented or punished. Another recent example of this sort of intrusion involved Tyler Clementi, a New Jersey student whose homophobic roommate surreptitiously filmed him kissing a man, before inviting friends via Twitter to watch. Clementi, who was 18 and had only just told his parents that he was gay, jumped off the George Washington Bridge.

Henry James was appalled by the extent to which such East Coast inventions as telegrams, flashbulbs and roll film were ‘newspaperising’ the world. He described their coarsening effects in several novellas, including The Reverberator (1888), about an American scandal-sheet. Its Paris correspondent foresees a time when news will be served up ‘from day to day and from hour to hour’ – and he can’t wait. ‘I’m going for the inside view, the choice bits, the chronique intime,’ he says. ‘What the people want is just what ain’t told, and I’m going to tell it … We’ll see who’s private then, and whose hands are off, and who’ll frustrate the People – the People that wants to know.’ Others were keen to check this journalistic juggernaut. Samuel Warren, angered by the Boston Daily Globe’s interest in his social engagements, persuaded Louis Brandeis, a fellow Harvard Law School graduate, to help him establish legal limits to the prying of newspapers. The outcome was an article in 1890 proposing that privacy was so valuable that its violation should be actionable.

Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual … the right ‘to be let alone’. Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the [biblical] prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.’ For years there has been a feeling that the law must afford some remedy for the unauthorised circulation of portraits of private persons [and] the evil of invasion of privacy by the newspapers … The question whether our law will recognise and protect the right to privacy in this and in other respects must soon come before our courts for consideration.

Warren and Brandeis’s ‘The Right to Privacy’ has good claim to be the most influential law review article ever written, with ramifications that have since determined US law on issues ranging from abortion to gay rights. But its impact on this side of the Atlantic was negligible. While Fleet Street was much taken by the inventiveness of American newsrooms and swiftly adopted not only their mechanical devices but also stylistic novelties such as banner headlines and face-to-face interviews, British lawyers saw little reason to follow the lead of Warren and Brandeis. They proceeded instead on the basis that privacy was adequately protected by established laws, the most significant of which was the right to sue for breaches of an implied or express duty of confidentiality. It was not until the mid-1990s, as pressures built for the incorporation into UK law of the European Convention on Human Rights (which guarantees ‘respect for … private and family life’), that judges reconsidered that stance. The turning point came when Hello! magazine was sued in 2000 by the actors Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones for publishing unauthorised photographs of their New York wedding. Although the parties had no prior relationship of trust which could have been breached, Lord Justice Stephen Sedley considered that unimportant; the time had come, he said, to recognise that people enjoyed privacy as a self-standing right ‘drawn from the fundamental value of personal autonomy’. A slew of celebrities proceeded to take advantage of this judicial shift. Naomi Campbell won damages over an illustrated Daily Mirror story, true but distressing, about her treatment for drug-dependency. The former Formula One president Max Mosley did the same in respect of a News of the World account of a ‘Nazi orgy’, persuading a judge that the report had embellished a relatively routine orgiastic encounter with false tales of fascistic role play. Recently, and notoriously, a few famous litigants were granted ‘super-injunctions’ – gagging orders that were themselves secret – on the basis that disclosure of the remedy would itself amount to an invasion of privacy.

Whatever one thinks of the merits of such rulings, they occurred only because there had been a failure of regulation. Had Parliament or the media industry instituted more effective ways of vindicating privacy after the Calcutt Inquiry, judges would not have found it necessary to plug the gaps. And there remains great uncertainty over what types of privacy are protected. In a case in 2003 concerning strip searches, Lord Hoffmann ruled that damages were ‘not recoverable’ unless there was provable psychiatric harm; whatever Sedley might have seemed to be saying in the Hello! case, Hoffmann made clear, his judgment should be understood as no more than a call for breaches of confidence to be renamed.

Leveson is consequently bound to consider whether Parliament should at last clarify the status of privacy claims, and is bound too to explore what that status should be. It is at least arguable that the answer is zilch. That was certainly the view of the former News of the World reporter Paul McMullan, who appeared before Leveson in November 2011. Now the landlord of a pub in Kent, he waxed nostalgic about his time at the paper. He repeatedly defended its intrusions by pointing out that readers had enjoyed the results. When asked about his contribution to a campaign to ‘name and shame’ paedophiles – an article that inspired an assault on a paediatrician – he observed that ‘in a bizarre way, I felt slightly proud.’ A startled Leveson wondered if he had misheard, and McMullan gave his response an empathetic spin: ‘I suppose I’m being a bit frivolous, but … you yourself wouldn’t like to spend your career in a back room, never having, you know, created or achieved anything.’ Then he became more solemn: ‘In 21 years of invading people’s privacy, I’ve never actually come across anyone who’s been doing any good … Privacy is for paedos, fundamental, no one else needs it, privacy is evil. It brings out the worst qualities in people … Privacy is the space bad people need to do bad things in.’

That assessment was as delusional as it was grim. But one aspect of McMullan’s evidence rang true. He had not forced his stories onto unwilling readers. If proof of the British public’s prurience and Schadenfreude were needed, it had come just four days earlier, when a survey reported that the total number of people reading Sunday newspapers had dropped by 3.3 million since the News of the World’s closure – almost half the tabloid’s average readership. Back in April 1989, when the Calcutt Inquiry was established, MPs were warned that ‘there is a cancer gnawing at the heart’ of the British press. ‘At the lower end of the tabloid market, journalism has been replaced by voyeurism. The reporter’s profession has been infiltrated by a seedy stream of rent boys, pimps, bimbos, spurned lovers, smear artists bearing grudges, prostitutes and perjurers … constituents say to members of Parliament: “Get on and do something about it.”’ The speaker was Jonathan Aitken, soon revealed as a seedy perjurer himself, whose misdemeanours, involving illicit hotel meetings with Saudi arms dealers, would come to light only because Guardian journalists used trickery to obtain his hotel bill and then refused to be cowed by his aggressive pursuit of a libel action.

Leveson will not need to be reminded about Aitken, any more than he requires advice on the weight to be given to McMullan’s testimony. But the central issue he faces could be expressed as a thought experiment involving both men. From now on, when a journalist of McMullan’s calibre intrudes on a citizen as respectable as Aitken, how should the conflict be resolved? The alternatives are equally unpalatable, but the very murkiness of the choice points towards some clear conclusions. Aitkens of the future should be entitled by statute to sue for breaches of privacy and get damages if they win. McMullans who are charged with criminal offences for publishing private matters should be acquitted if they show that intrusion was in the public interest. In some situations a heroic McMullan could be found to have justifiably revealed an act of moral turpitude. In others, the trysts of an embarrassed Aitken might seem to have deserved secrecy – as the case of Tyler Clementi shows, such situations are far from inconceivable. And because it is so hard to decide these matters in the abstract, it is crucial that cases be heard, in every instance by a jury: the arbiters need to be seen to be legitimate.

Empowering jurors to assess privacy actions and public interest defences to disclosure would generate formidable opposition. Many think privacy too nebulous a concept to protect and would worry, as the Sun did after Max Mosley’s courtroom victory, about ‘a dangerous European-style privacy law’. But protections for privacy are not the product of airy-fairy Continental theories. Warren and Brandeis were the first to articulate the right, and they cited English precedents in 34 of their 53 footnotes.

Were reforms to be discussed in Parliament, MPs would have to deal with many tricky issues. Should a new privacy law allow a remedy for frivolous or vicious disclosures which are true? Should there be a right to seek exemplary damages, so that newspapers cannot simply calculate in advance whether an intrusion would be worth their while? What factors should a criminal jury be able to take into account when weighing the public interest in disclosure? Can the public be persuaded that new rights to jury trial are not just a job-creation scheme for lawyers? But the prize is great – an end to the cycle of scandal and inquiry – and no one is in a better position to offer solutions than Lord Leveson.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.