In 1991 the art critic Louisa Buck rang me up – she was my sister-in-law and in those days we didn’t text – and said I really should go along to Bond Street and see the butterflies hatching in some disused premises that the artist Damien Hirst had rented. ‘It’s a truly beautiful installation,’ she enthused. She described it: the dishes of melting nectar, the chrysalises stuck to the walls, and the startling epiphanies as the creatures unfurled, fluttered – tropical, iridescent, huge, ineffable. I didn’t get there in the end, but not because I didn’t want to. Now the piece has been reconstructed in Hirst’s retrospective at Tate Modern, and for many reasons I wish I had seen the original version of In and Out of Love. It mattered then and it matters now that Hirst rented the space, a former travel agency, so that he could install his vision of natural beauty and the life cycle, there, in the heartland of platinum-plated consumerism and high fashion. Like one of the gorgeous brindled or turquoise insect mimics he hatched, he was taking colour from his surroundings and showing he could make exquisite artefacts, delicately skilful, each one unique, precious, rare: he could show how supremely wonderful a real creature is, more so than anything at Asprey or Prada or Cartier.

There’s a tempting museum shop at the exit of the show at Tate Modern (currently selling numbered Hirst prints for more than £30,000 each), but the oblique claim made by Hirst’s early work has faded from view. That claim was manifold, and it was first and foremost a kind of guerrilla tactic, to take art into the redoubts of luxury and money: an artist could be a raider, a member of a flying squad, an Occupy-style activist parachuted in to transform and shock. The YBAs as a group held street markets, improvised shops and mail order art (Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas together), and installed their work in unusual and distant derelict sites (their inaugural, epoch-defining group show, Freeze, at Surrey Docks, which Hirst curated). Seen in a room in a national monument the work inevitably loses the social defiance and implicit mockery of that first daring improvisation.

Just upriver from the Tate, the exhibition Invisible: Art about the Unseen (at the Hayward until 5 August) makes the point about the crucial role of topography, institution, description, naming: one empty white room after another, each of them different, and each of them revealing. A space cooled by an air-conditioner that is recycling water from the morgue where the corpses of victims of Mexico’s drug war are washed (Air, 2003, by Teresa Margolles) gives a very different feeling from the white cube called The Air-Conditioning Show (1966-67) by Art & Language, an angry manifesto about the way ambience creates value. It sounds insane to fill the Hayward with invisible works of art, but though it seems an arrant example of the emperor’s new clothes, the show gives an exhilarating lesson in looking and paying attention, and incidentally provides the history behind the forms that conceptual art took in the 1990s, whose gaudy precipitate is the phenomenon of Damien Hirst.

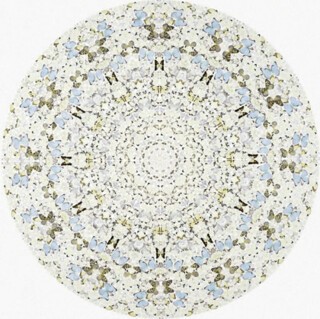

There’s a tendency in writing about Hirst to become portentous and metaphysical, and I don’t want to fall into that mode. But Hirst is a symbolist and his symbols reach for transcendence. He chose butterflies, the most metamorphic of animals, for his poor artist’s radiant boast in 1991, and in 2011 he published a book of images of metallised butterflies identified by colour as in a paint chart, and entitled it The Souls. The installation on Bond Street introduced time into the vision of souls, bliss, beauty: Hirst’s objets de vertu were ephemeral, and fell to the ground after their short span was done. They invert the usual definition of art as eternal, countering time and decay.

The words tempus and temple share the same root; the connection suggests that the function of a sacred space is to make time stop or stretch, or render its passage palpable to the worshipper/visitor. Galleries and museums explicitly recall temples in their architecture, and they can also double as national mausoleums: they function socially in comparable ways (‘temples for atheists’), providing an occasion for assembly, for communal experiences, for finding meanings. Above all, it’s striking how crucial the idea of developing our sensitivity to time has become in contemporary artists’ work. ‘I do not think I am slowing down time,’ Tacita Dean, one of the most delicate time machinists of all, said recently, ‘but I am demanding people’s time. In a busy world, that is a big demand, but one of the many reasons why art matters is its ability to stop the rush. Art on film makes us conscious of the time and space we occupy, and gives us an insight into the nature of time itself.’

The afterwardness of experience adds layers to memory: a first time keeps changing as it is successively remembered and relived. In the case of Damien Hirst, three decades of glory, combined with the judicious pruning of this retrospective, have altered our response to his work: they’ve attenuated the sensationalism, far more so than with the art of Francis Bacon, whom he admires and emulates. It’s as if the works themselves have swallowed all the barbiturates and decongestants displayed in those gleaming cabinets. So many of them have become iconic that they now wear a classical, self-important air. Hirst taught us to look at cows’ heads weltering in their own blood and buzzing with flies (A Thousand Years), and we have learned to do this too well, without flinching. The Tate show is full of young children with clipboards and question sheets, and they’re running about, giggling at escaped butterflies and ticking off their finds (three flayed sheep’s heads, a thousand cigarette butts, one hairdryer, ten thousand dead flies) as happily as they do among the mummies at the British Museum or the crucifixions and pietàs of the National Gallery.

The butterflies, the skinned carcasses, the stuffed shark and the cloven cow and her calf could belong in a Wunderkammer, but Hirst’s way with these natural specimens differs from his precursors’ collecting habits. A 17th-century prince was moved by a scientific impulse of wonder and wanted to possess natural phenomena for their intrinsic marvellous properties, not primarily for their signifying afterglow. Hirst, by contrast, looks beyond the thing itself to what it means. He’s a natural allegorist, a lover of vanitas images – a clear case, I think, of once a Catholic. Although he stopped attending Mass when he was 11, the Jesuits or whoever was teaching him catechism had had quite long enough to shape him for ever. He is named after the patron saint of doctors (usually spelled Damian), who, with his twin brother Cosmas, performed the first surgical transplant when he grafted the leg of a Moor who had fallen in battle onto the stump of a white Christian knight. This operation, depicted on altarpieces in the saints’ many churches, can’t be consigned to the antique glory hole of weird Catholic legend, for it was crucial to Joseph Beuys’s dream of revolution: a vision of inter-racial fusion, of the resurrection and reconciliation art can achieve. In one of his works, Beuys eerily renamed the two towers of the then newly built World Trade Center after the brother saints: did he do so in some wan hope that the towers could be transfigured into instruments of good?

Beuys, needless to say, is second only to Duchamp in importance to the current philosophy of making art. Hirst took to heart Duchamp’s message that the action of naming turns anything into art, but his education at Goldsmiths added to this sometimes rather austere cleverness the sparkle of his teacher Richard Wentworth’s playfulness (Hirst’s hairdryer and ping pong ball from 1994, called What Goes Up Must Come Down, has the punning neatness of Wentworth’s work). The English comedy of early Gilbert & George and a complicated mockery of class allegiance also lift the solemnity of Hirst’s symbolism. His titles range from prayer-like rigmaroles (Beautiful inside my head forever) – known in Catholic parlance as ‘ejaculations’ – to unadorned litanies of words and direct invocations of Paradise and its opposites (Sinner, Judgment Day). The scientific names of polysyllabic substances stand in for unfamiliar saints, following Hirst’s equivalence between belief in religion and belief in medicine, which he associates with going to the chemist’s with his mother and her blind faith in the prescriptions her doctor was giving her. And, of course, there’s the necrophilia.

Memento mori used to be a sign of profound Christian virtue: a pious man or woman would commission a tomb which showed them alive and fully dressed above, and in a vivid state of wormy decomposition below. There are some splendid 17th-century examples in the Louvre; grisly decomposing skeletons also figure, more unexpectedly, on later English tombs in Westminster Abbey. By taking stock of the horror, warding it off, the artists perform a kind of sympathetic magic of containment on their own behalf and on behalf of their patrons. Visions of mortification in many of Hirst’s works arise from a similar motive. The anaesthetic effect of Hirst’s work, now that the shock has worn off, shows how effective this process can be. Mother and Child (Divided) is a profane yet tender Madonna, a pietà that’s a comment on abattoirs, carnivorousness, mad cow disease and other things – but the spectacle has become familiar. I can almost look at it now without looking away, though when some visitors asked me if there was a lamb in the womb of the cow, I found it difficult to examine the dark cauliflower in the gut which they were taking for fleece.

The reason for Hirst’s classic status lies partly in this symbolic emphasis. It used to be undercut by cheek, delinquency and the kind of gallows humour the YBAs relished: there’s a disturbing video in the show, A Couple of Cannibals Eating a Clown (I Should Coco), from 1993, in which Hirst and Angus Fairhurst are both in full clown fig, with ruffs and slap, exchanging macabre stories of maimings and butchery, crashes and crimes, all the while drinking and smoking; every now and then Hirst squeezes a toy horn, and they get the giggles. But on the whole it’s an exercise in callousness. Hirst’s game of chicken soon began to pall.

He’s now playing for real and for very high stakes. Can value be added literally to a work of art? Once, nature’s own artistry did it for him: the butterflies, the lambs, the sharks. Fabrication followed: the properties of proprietary medicines, the gleaming and cunning tackle of surgical instruments, the splendour of tropical butterflies mounted in kaleidoscopes of colour to create stained-glass windows (Doorways to the Kingdom of Heaven). Now, in the latest phase of his work, he is harnessing craft of the highest technical standard: gem-cutting as can only be done today, with precision tools and the nano-calculations of the cyber-age.

Some of the votive offerings of the past were highly wrought: their efficacy was bound up with the intricacy and technical complexity of the artefact. The anthropologist Alfred Gell, in his study Art and Agency (1998), took the prows of Papuan war canoes as his prime example of magical prophylaxis: the brain-teasing involutions of the carving were intended to bamboozle hostile forces. Gell argued that the approaches anthropologists use to understand the meaning of art and aesthetics in a culture that is not their/our own should be extended to explore contemporary art at home; and he showed that similar desires are in play when artists make objects as instruments that exert some kind of power on their surroundings, either to make things happen (to assure health, fertility, luck in love, wealth, cleanse a pollution), or to stop things happening (to prevent death, destroy enemies, ward off nightmares, avert revenge). Rather than inquiring into phenomena by representing them, as Monet magnificently struggled to do with the Nymphéas series or the façade of Rouen cathedral in different light and weather, surrealist artists and their kin – conceptualists, performers, language artists – began using mimesis according to the principles of magical thinking, as a talisman: you reproduce the horror to avert it. Hirst’s anatomies are closer to relics than to Rembrandt still lifes. His glittering medicine cabinets, now exhibiting dazzling zirconia crystals as well as pills, are tabernacles as lustrous as Counter-Reformation propaganda for the Eucharist. Even the spot paintings, which have a look of pretty minimalism (and have been much copied by packaging and fashion), reveal an allegorical higher purpose through their titles, while the reiteration, multiplicity and essential meaninglessness of the spots relate them to the processes of charms and spells – often nonsensical, always repeated.

The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, to whom Hirst is greatly indebted (as he acknowledges and she likes to recall), has painted spots obsessively since the 1960s, and in her work they convey her own mental disturbance, a hallucination of ‘infinity nets’ spreading over the universe. The titles of Hirst’s spot paintings invoke various chemical substances, poisons as well as others; this produces, at least to my ears and eyes, a straining for the kind of higher meaning that Kusama achieves gracefully and poignantly. There’s a space of mystery in her art: we can’t know what she is experiencing, only glimpse it.

By contrast, Hirst’s desire to speak in symbolic images ultimately outruns his imaginative energy. His paradoxical effort to be in control of his own human fears and instincts, of his mortality, of his fortune, leaches the enigma and vitality from his work. A stuffed white dove hovering in a vitrine (The Incomplete Truth, 2006), remains at a level of literality that leaves no breathing space for the viewer. When Paul Ricoeur was thinking about the working of metaphor in The Symbolism of Evil, he pointed to the necessary enigma of the thoughtful symbol: it ‘does not conceal any hidden teaching that only needs to be unmasked for the images in which it is clothed to become useless’. He suggests that symbols should be thought of as a gift to reflection, ‘an occasion for thought, something to think about’. The door must not slam on reverie.

The word ‘symbol’ has unexpected but revealing origins. It is derived from the Greek verb ballein, ‘to throw’, as in the geometrical figure of the hyperbola for a cone that’s extended far from its base: thrown wide, as it were, as in ‘hyberbole’. It persists in diabolus, Latin for ‘devil’, where it evokes the devilish work of throwing everything apart and athwart, scattering into disorder and cacophony. Symbol means ‘thrown together’, and it was first used to describe a tally, a coin, token or stick cut in half to solemnise an agreement, which would be concluded when the two parts were joined together again. ‘The one [part] in my possession,’ Eugenio Trias has explained,

is the ‘symbolising’ component of the symbol. The one elsewhere is needed to gain meaning … [and] the disjunction between these two parts … constitutes the horizon of meaning … The drama (of their conjunction) leads towards the final scene of reunion and reconciliation, in which both parts are ‘pitched’ into their desired coming together.

This site of conjunction is key to the effect of a work of art in the symbolic mode; what happens there gives the artefact a quality of presence, makes it radiate significance, sometimes quite softly, but still irresistibly and ultimately ungraspably. Then you want to go on looking, and looking again.

What is the halo of art that radiates beyond the viewer’s ability to comprehend it? How can this happen? Ricoeur keeps to philosophy and language, but he identifies a crucial difficulty: the transition between the subjective thinker and the community in which the thought is formed, along with its wider historical continuum. He emphasises the dynamics of this mutual exchange, and reminds us that Plato warns, in the Charmides, that ‘gnothi seauton’ (‘know thyself’) is not enough if one is simply gazing at oneself in the mirror: such knowledge can be gained only in the complexity of social interaction.

There are too many equations in Hirst’s art, too many comprehensible metaphors with no outer rings of mystery and resonance; he doesn’t voyage into those spaces of thought between the outer code and the referent. There is nothing compelling you to look at his works for long, not only because of the way they’re made (with the exception of that jeweller’s masterpiece, the diamond-encrusted skull, bling bling though it is), but also because as he’s grown older and richer, the glee with which he mocks death has needed a stronger fix to feel real. His limitations as an artist are bound up with the transparency – you could say the obviousness – of his symbolism.

Votive offerings, spells as artefacts, used to be very costly: it adds potency if you’re prepared to invest in the embodied prayer, the wish wrought into a thing. Metaphysical symbols of value gain efficacy from vehicles of value: crushed lapis lazuli, or Mary’s blue, ‘the sapphire that turns all of heaven sapphire’, was the most expensive pigment in the world after gold. I remember visiting the cathedral in Zaragoza: the sacristan swung open the huge heavy doors of the treasury, where gifts to Nuestra Señora del Pilar, Our Lady of the Pillar, were kept. A blaze of diamonds burst from the dark cupboard: emeralds, rubies, gold, crystal, every precious gem and mineral cut and polished and set into adornments for her statue. The kings of Spain, and then General Franco, were leading donors (it strikes me that the Church could part with some of this bullion to help the country). The Virgin was being supplicated: these artefacts were the most valuable things that could be wrought to propitiate the vengeance of heaven.

The notorious skull is called For the Love of God, after a remark of Hirst’s Irish mother, he tells us: ‘For the love of god, whatever will you think of next ?’ It’s a knowing imitation of the calaveras of the Mexican Day of the Dead, though they’re often made of sugar. The diamonds shoot light wonderfully, sparkling with the colours of the spectrum. Yayoi Kusama’s show at Tate Modern, which overlapped with Hirst’s for a while (it closed in June), climaxed in a hall of mirrors lit by tiny spheres that moved through the spectrum in a random sequence reflected ad infinitum as in a fairy planetarium. She made it first in 1965 and it’s called Infinity Mirrored Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Life. The colours were the same as those from Hirst’s diamonds, and it was comforting for the visitor that only one guard was needed at the door.

Hirst’s iridescent skull is missing a tooth, though the rest of its former occupant’s gnashers have been polished for their eternal prestigious preservation in the multi-million-pound platinum gums and jawbone. Talking about his diamond-encrusted skull, Hirst explains: ‘I just want to celebrate life by saying to hell with death.’ One of the earliest exhibits in the Tate exhibition shows Damien as a 16-year-old urchin, snaggle-toothed and grinning, beside a cadaver’s head in the Leeds University anatomy department. The missing tooth makes the diamond-encrusted skull a living thing; it brings back the Yorick in the artefact; it turns it into a self-portrait.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.