From the moment he died in April 1590, Francis Walsingham, principal secretary to Elizabeth I, has been the subject of competing myths. Catholics greeted the demise of a relentless opponent with relief and applause, and circulated lurid providential stories about the appalling stench that came from his corpse, which allegedly poisoned one of his pall-bearers. By contrast, Protestant writers – William Camden was one – praised his unswerving allegiance to the queen, his tireless dedication to the reformed religion, and his genius as ‘a most subtil searcher of hidden secrets’.

Confessional sentiment has continued to colour accounts of Walsingham in the centuries since. He remains an ambiguous figure, celebrated as a brilliant statesman and pioneering head of espionage who saved the last Tudor monarch from assassination and protected the English state from invasion by foreign powers, and denigrated as a Machiavellian politician who masterminded a campaign of intimidation against Catholic missionary priests and engineered the downfall of Mary Queen of Scots by methods of the most dubious morality. Building on the classic image of Walsingham as spymaster established by James Anthony Froude’s History of England from the Fall of Wolsey to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada (1856-70), his early 20th-century biographers, Sidney Lee and Conyers Read, presented him as an astute and distinguished patriot who laid the foundations for the modern security services. But then Read’s three-volume study of 1925 reflected his own political preoccupations and professional activities, particularly his role in establishing the Office of Strategic Services, precursor of the CIA, in the decades before the Second World War. More recently, especially on TV and film, Walsingham has been portrayed as an enigmatic figure, driven by hatred and bigotry, who orchestrated shady undercover operations carried out by a motley crew of spooks. His depiction in the 1998 film Elizabeth as a gay godless politique has little foundation in fact, though the film did capture the obsessive concern with protecting the queen from assassination that so evidently animated him. Described by one 16th-century Spanish ambassador as blunt, uncourtly and dressed always in black, Walsingham has long defied categorisation.

John Cooper’s book is a fresh attempt to assess the accuracy of these opposing images. It charts Walsingham’s life from his birth in 1531 or 1532, on the cusp of the Henrician Reformation and the break with Rome, through his education at King’s College, Cambridge, the Inns of Court and abroad, to his posting as English ambassador in Paris at the time of the Wars of Religion. The out-of-pocket expenses of this diplomatic office, he complained, were ‘like to bring me to beggary’: the compensation was valuable experience and close relationships with senior figures in the Elizabethan regime, such as William Cecil and Robert Dudley. His activities abroad were instrumental in his appointment as principal secretary to the queen in 1573, which marked the beginning of nearly two decades of virtually uninterrupted activity at the heart of government. Cooper’s portrait necessarily rests on a study of state papers, since, apart from two semi-official diaries or ledgerbooks, Walsingham’s personal correspondence and memoranda don’t survive. This book therefore privileges his public role at the expense of his private experience. Little can be gleaned about his marriages to the wealthy Londoner Anne Carleill, who died childless just two years after they married in 1564, and then in 1566 to the widow Ursula Worseley, with whom he had two children. His sole surviving daughter, Frances, married the poet and Protestant courtier Sir Philip Sidney. Cooper acknowledges the problems these gaps in the record pose to a biographer, but doesn’t shy away from sifting Walsingham’s motives and gauging the nature and depth of his religious beliefs.

For Cooper, Walsingham is a man of principle fundamentally shaped by his commitment to godly Protestantism. His faith was nurtured by his mother, Joyce Denny, sister of the evangelical courtier Sir Anthony Denny, and shaped by his exposure to the advanced Protestant ideas propagated by John Cheke, master of King’s and tutor to Edward VI, and Martin Bucer, the Strasbourg theologian and Regius Professor of Divinity in Edwardian Cambridge, as well as by his years in Basel, where English exiles gathered during the reign of Mary I. There he shared lodgings with the martyrologist John Foxe in a former convent called the Clarakloster; Foxe dedicated three books to him. Cooper infers that Walsingham ‘drank deeply from the wellspring of reform’ and may have been implicated (with other members of his family) in support for Lady Jane Grey and in Thomas Wyatt’s rebellion against Mary of 1553-54: perhaps this was one of the reasons he fled England shortly afterwards. No less formative was the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572, when thousands of Protestants were slaughtered by their Catholic neighbours in Paris and provincial cities. He witnessed the ‘most horrible spectacle’ in Paris and attempted to protect several Huguenot friends at some risk to himself.

Keen to emphasise Walsingham’s high ideals, Cooper contrasts his choice of exile with the nicodemite conduct of his future colleague William Cecil, who opted for compromise when Mary came to the throne and even accepted the Mass in his private chapel to secure his place in the administration. Cooper underlines the ‘sharp divide’ between them in the 1550s: ‘One with a politician’s pragmatism, the other unwilling to be a reed bending before the wind.’ Stretching the evidence at his disposal, he presents Walsingham as a noble exception in an Elizabethan privy council full of men who had tailored their religion to suit the previous Catholic regime. This, Cooper writes, was ‘a man who could not be lured from his faith by the promise of patronage’, and whose approach to foreign policy was driven by a sense of responsibility for the ‘advancement of the gospel’. He was an energetic advocate of intervention in support of the Calvinist cause in the Habsburg-ruled Netherlands; he promoted initiatives to help the Dutch rebels against Philip II’s governor general, the Duke of Alva; he offered military assistance in the wake of William of Orange’s assassination in 1584. Walsingham’s convictions made the prospect of Elizabeth’s marriage to a French Catholic as odious to him as the yoking of Christ with Belial. Nevertheless, his distaste for the proposed matches with the dukes of Anjou and Alençon that dominated Anglo-French relations in the 1560s and 1570s was counterbalanced by the urgency of resolving the succession and securing an ally against England’s arch-enemy, Spain. He saw these dynastic alliances as necessary concessions in a larger strategic game designed to defeat the forces of the anti-Christian papacy. Insisting that Walsingham followed his conscience when it came into conflict with his duty to queen and country, Cooper suggests that there are times when he resembles his predecessor as principal secretary, Thomas More, executed for refusing to endorse the royal supremacy in 1535. The plausibility of this ‘eccentric comparison’ may be questioned. It is certainly in keeping with Cooper’s transparent determination to recast Walsingham as a hero.

In particular, The Queen’s Agent seeks to exonerate him from the charges levelled by the Jesuit historian Francis Edwards, according to which he is supposed to have used torture to force Sir Francis Throckmorton to ‘confess’ his involvement in a treasonous scheme to help the Duke of Guise invade England and overthrow Elizabeth, and to have fabricated the Babington Plot in order to get Elizabeth to agree to the execution of Mary Stuart and so justify the obliteration of English Catholicism. Cooper rightly dismisses the wilder parts of the conspiracy theory, but his efforts to evaluate the ethics of Walsingham’s intelligence-gathering activities and to decide whether he was guilty of entrapment steer him into difficult waters. Walsingham was behind the ingenious intelligence operation by which Mary’s letters to and from Anthony Babington passed through his office and were deciphered before being sent on, making it possible to incriminate the Scottish queen in July 1586. And he was responsible for the addition of a postscript that led Babington to name the accomplices to his plan to assassinate Elizabeth, a step that Walsingham subsequently worried had bred suspicion and ‘jealousie’. He defended himself against Mary’s allegation that he had falsified evidence, insisting that he had ‘done nothing unbeseeming an honest man’ and ‘unworthy of my place’, except to act in the interests of his sovereign and her realm. Cooper’s biography doesn’t wholly resolve the tension between Walsingham’s evident loyalty to the crown and the apparent brutality of his pursuit of those who endangered national security.

Quoting rather sparingly from his writings, Cooper never quite succeeds in opening a window into Walsingham’s mind. His outbursts against seminary priests – the ‘poison of this estate’ – and his belief that that ‘devilish woman’ Mary Queen of Scots was a ‘wicked creature ordained of God’ to punish England for its sins afford glimpses that might have been more fully analysed. Nor is his chequered working relationship with Elizabeth closely examined: the queen referred to him almost affectionately in one letter as ‘her Moor’ but also resented his role in precipitately executing the warrant for her cousin’s death. While the ‘plangent Puritanism’ that allegedly aggravated relations between them is hard to recover in the absence of so many of his papers, his links through marriage with leading lights of the godly cause – Sir Walter Mildmay, founder of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and the MP Peter Wentworth, who agitated for further reform of the English church and its liturgy – may deserve further attention. He once declared that ‘I would have all reformations done by public authority. It were very dangerous that every private man’s zeal should carry sufficient authority of reforming things amiss.’ Although there are a few hints of hostility towards the institution of episcopacy, he apparently had little sympathy with those who refused to ‘tarry for the magistrate’. But it remains difficult to access Walsingham’s devotional and spiritual life. There is a rare expression of his perfervid predestinarian faith in the preamble to his will, when, Cooper suggests, we hear him in prayer. Breaking away from conventional phrases, he assured himself

that Jesus Christ my true and only Saviour of his great and infinite mercy and goodness will vouchsafe not only to protect and defend me during the time of my abode here in this transitory earth with his most merciful protection (especially in this time wherein sin and iniquity doth so much abound), but also in mercy to grant unto me, by increase of faith, strength and power to make a good and Christian end.

He forbade any of the ‘extraordinary ceremonies’ due to men who served in high places and was buried quietly in the same tomb as his son-in-law, Philip Sidney.

Ironically, in much of the book Walsingham hovers off stage. His life is a convenient hook on which to hang a vivid if familiar narrative of Elizabethan politics, high treason, court faction and international intrigue – a faintly triumphalist story of England’s struggle to combat the quadruple menace of the papacy, the Catholic League, Philip II and the Spanish Armada. Cooper’s book skilfully reflects dominant trends in current historiography, but rarely breaks out of the interpretative moulds set by the secondary literature it relies on. In presenting Walsingham as a clever cajoler and manager of the queen’s emotions and whims, adept at ‘swerving from the precise course of her majesty’s instructions’, Cooper follows recent commentators who have underlined the limits of royal power in 16th-century England. His depiction of Elizabeth’s regime as a ‘monarchical republic’ dependent on the co-operation of her councillors and citizens echoes the influential thesis of the late Patrick Collinson. Walsingham’s status as a critical part of the ‘Heath Robinson machine’ of Tudor government – attested by the politician and historian Sir Robert Naunton, who described him as the ‘engine’ of the state – is well established. But the claim that his exile in Reformation Germany and Renaissance Italy sowed the seeds of radical resistance is less convincing. There is insufficient evidence for the suggestion that his exile in Basel and Padua during Mary’s reign was an apprenticeship in the sort of subversive thought that found its most notorious expression in John Knox’s First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558).

Cooper is on firmer ground in his account of the network of spies, double agents and cryptographers Walsingham assembled in the 1570s and 1580s, and who clustered around his house in Seething Lane near the Tower of London (the Victorian office block now on the site still bears his name). Though he can’t entirely resist comparisons with MI5, MI6 and the code-breakers of Bletchley Park, he is careful to emphasise that the early modern security services were more a ‘web of relationships’ than a formal organisation. His book casts light on the contributions made by the gifted linguist Thomas Phelippes and the physician Timothy Bright to theoretical and practical advances in the science of cryptanalysis. It is also illuminating about the underworld of turncoats and opportunists in which Walsingham immersed himself and whom he suborned and corrupted with promises of money, sometimes getting his fingers burned. It shows him co-ordinating an eclectic assortment of playwrights, suspected homosexuals, soldiers, zealots and traitors in a dangerous game that always had the potential to backfire catastrophically. Among these agents were the Catholic priests Gilbert Gifford and Anthony Tyrrell, slippery figures who crossed confessional boundaries and betrayed their masters more than once. Another was Christopher Marlowe, whose casual employment by Walsingham in 1587 and sordid murder in Deptford six years later, has fuelled a minor literary industry. Surprisingly, Cooper doesn’t mention Henry Fagot, a key figure in his intelligence-gathering activities against Mary Stuart in France in the mid-1580s, whom John Bossy identified as the notorious Dominican friar, natural philosopher and heretic Giordano Bruno.

The most original chapter in this biography concerns Walsingham’s role in the promotion of English plantation in Ireland and America. Here Cooper’s research is more impressive. It extends our knowledge of Walsingham’s range of interests and of the connections between conquering and settling the queen’s second kingdom and colonising the New World. In championing the planting of Ulster and Munster, Walsingham played his part in consolidating royal control of Ireland by force, suppressing noble Catholic rebels, sanctioning a ‘scorched earth policy’ of conquest, and, indirectly, fostering ethnic and religious tensions that erupted into sectarian conflict during the following century. Highlighting Walsingham’s friendships with the mathematician and astrologer John Dee and with Richard Hakluyt (who dedicated Principall Navigations to him), Cooper also investigates his links with the efforts of his stepson Christopher Carleill to create a colony on Roanoke Island off the coast of North Carolina in 1586. Carleill’s 1583 Discourse upon the Hethermoste Partes of America had provided a manifesto for settlement in the New World: the godly traders he led across the Atlantic would have no ‘confessions of idolatrous religion enforced upon them, but contrarily shall be at their free liberty of conscience’. Roanoke Island was supposed to be a new Jerusalem, a city on a hill. Cooper presents Walsingham as a supporter of colonisation a generation before such ideas became conventional and alerts us to a neglected dimension of the prehistory of Puritan New England.

The new aspects of Walsingham’s activity revealed in Cooper’s book enhance our understanding of a figure who not infrequently yearned to be free of the burdens of public office. He wrote in 1576 of his desire ‘to be quit of the place I serve in, which is subject unto so many thwarts and hard speeches’, and observed to William Cecil in the anxious weeks leading up to Mary Stuart’s execution that the happiest men at court were ‘rather lookers-on than actors’. In a letter to one of his nephews written later in life, he wryly characterised the function of men of state as ‘conduit pipes, though they themselves have no water’. Often bed-bound by urinary tract infections that may indicate diabetes, Walsingham displayed a stoicism in the face of physical suffering that Cooper suggests added an edge to his Calvinist spirituality.

The images that emerge from this book complicate the stereotypes that have accumulated around Walsingham in the last five hundred years. Ultimately, though, it struggles to get behind the watchful blue eyes of his surviving portraits. Walsingham remains a mysterious jumble of contradictions, a consummate keeper of secrets – and of none more closely than his own.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

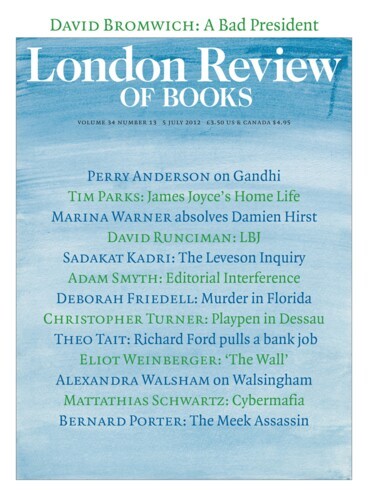

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.