A static shot, as always. On screen, in the sunshine, a bright yellow combine harvester is toiling across an Oxfordshire wheatfield like a paddle steamer in reverse, churning up a mist of chaff and dust. The machine growls very slowly out of sight – any second now the scene will surely cut away. But here it comes again from left to right, the camera still unmoving and far enough from the action, such as it is, to obscure the tiny figure in the vehicle’s cab. This goes on for some time: three passes, if memory serves, though it seemed like more. Until at length a swift cut. To what? Another shot of another combine harvester, labouring up and down another field, diagonally, this time accompanied by a blue tractor.

This pairing of views in Patrick Keiller’s 2010 film Robinson in Ruins – glimpsed again as part of his current installation at Tate Britain (on display until 14 October) – is almost too typical to be true and must, among other things, be a joke at his own expense. Since the early 1980s Keiller’s work has combined extremely laconic imagery – schooled on English landscape painting and the industrial photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher – with more or less ironised, more or less fictional, increasingly erudite voiceovers. His first film, Stonebridge Park (1981), was a piece of glumly comic suburban noir: black and white footage of a motorway bridge and a railway footbridge in North-West London accompanied the narrator’s tale of petty theft and attempted murder. Keiller took the austerity of 1970s structural film and conceptual art, and filled their narrative voids with a voice that seemed to belong to a type of rambling English essayist who was also – somehow – a visionary devotee of surrealism and the Situationists.

Keiller’s methods paid off impressively in London (1994) and Robinson in Space (1997), the first two films to feature – if that’s the word to suit an unseen ‘character’ who is more rumour than solid invention – the peripatetic scholar Robinson, a stand-in for the more delirious side of the filmmaker’s researches into landscape and urbanism. In the first film, Robinson imaginatively repurposes drab districts of Major-era London as monuments to Continental romantics and modernists. (Like some ruinously well-read Blairite of the mid-1990s, he fondly believes Britain will be a better place when it is texturally more like Europe.) In the second, Robinson and a long-suffering narrator-companion, voiced in both films by Paul Scofield, set out to solve ‘the problem of England’: the advent of a new exurban landscape of logistics sheds and information hubs, bristling at the edges of cities that have failed to flourish as post-industrial enclaves for leisure and service.

Robinson in Ruins, which plays without its voiceover at the centre of Keiller’s commission for Tate’s Duveen Galleries, is the third film in this not quite a series, conceived just as recession loomed over the economy and architecture that Keiller had explored in Robinson in Space. It shares much with the first two: the immobile camera frames bits of anonymous infrastructure and residual pastoral, mostly filmed not far from Keiller’s home in Oxford, and the whole is propelled by a story about land use and power over several centuries, voiced this time by Vanessa Redgrave. But it is in some ways a different proposition from London and Robinson in Space. The film arose in part out of a research project called The Future of Landscape and the Moving Image – an academic collaboration with the geographer Doreen Massey and the cultural historian Patrick Wright – and it’s altogether more sober, less playfully immersed in the faintly mad worldview of Robinson, who has anyway vanished, presumed dead. But he has left behind his notes and the footage from which the film has notionally been constructed. Robinson in Ruins seems more provisional than the other films, part of an unfinished argument, and maybe therefore better suited to what Keiller has done at Tate Britain, which is essentially to expand the film, and the whole conceit of Robinson the scholar, into an installation-cum-exhibition drawn from the gallery’s collection.

The Robinson Institute is the result of Keiller’s trawling the Tate archive, initially online, and selecting 120 works – a few are drawn from other museums and libraries – to be attached to a series of metal frames that extend through the long galleries. The exhibition style seems apt: the sort of Bauhaus-meets-minimalist gesture of which Robinson would approve, but with an echo too of the Mnemosyne Atlas, the set of wooden frames and panels on which the art historian Aby Warburg made associative maps of Western art in the 1920s. Some of Keiller’s choices, interspersed among video screens showing more footage from his film, are direct reminders of Robinson in Ruins and its vagrant take on the history of English landscape, more specifically on the ways the countryside around Oxford has been ploughed and parcelled by aristocratic landowners, heavy industry and the UK and US military.

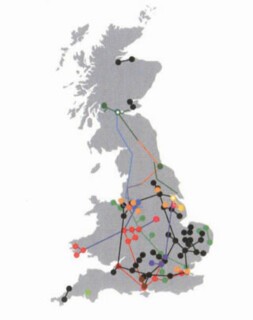

In fact, one could construe the show mostly in terms of its historical-political subject matter, which is extremely varied, but circles around the topic of land and its use, and the constellation of commercial, political and military interests involved. So here is Turner’s Harvest Home (1809), with its crowds of revellers and merchants and produce piled high, juxtaposed with Andreas Gursky’s Chicago, Board of Trade II (1999), a typically vast (and partly fantastical) photograph of a teeming trading floor. Here is Paul Nash’s Totes Meer (1940-41): its pile of wrecked German aircraft, compositionally modelled on a frozen sea by Caspar David Friedrich, was in fact discovered by the painter at the Morris car works at Cowley. Keiller pairs it with a French advertisement for the Morris 1100, an image of an economic future for British manufacturing that never came. In Keiller’s cartography, there is always some secret affinity or passageway to be divined, like the connection between 18th-century road maps, the romantics’ walking excursions and a chart of the Government Pipeline and Storage System, which since 1942 has served the interests of oil companies, the Ministry of Defence and the US Air Force.

You can easily get drawn into the web of Keiller’s connections. He has a knack for making port statistics, the lichen patterns on a motorway sign or the remains of a cement works in Shipton-on-Cherwell suddenly seem like the key to our contemporary cultural-political moment. Which is why The Robinson Institute, for all the persuasive correspondences it divines among historical representations of British landscape, can’t be read as a work or a show with a strict thesis. It is also very much about Robinson’s (and therefore Keiller’s) way of seeing: a protracted, melancholic and almost occult concentration out of which his insights or intuitions eventually emerge. It’s visible in some of Keiller’s choices of artwork: the Bechers’ coal bunkers from 1974, August Sander’s Vagrants of 1929, chemical scroll waves photographed by Fritz Goro in the 1980s. But it’s already there in the film around which these works describe a fascinating constellation. In one of the longest shots in Robinson in Ruins, outdoing even those slow, tireless combines, the camera lingers on a gently nodding foxglove, and Vanessa Redgrave coolly informs us that Robinson suffers from biophilia, an affliction of surrealists. In fact, his attention, if not Keiller’s, is keener than that: he believes, we’re told in the second Robinson film, that ‘if he looked at the landscape hard enough, it would reveal to him the molecular basis of historical events.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.