Titian’s Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto were described by Lucian Freud as ‘simply the most beautiful pictures in the world’. And not long ago, in an act of Alex Salmond-defying co-operation, the National Gallery of Scotland and the National Gallery of Great Britain raided their respective coffers – as well as the coffers of their respective, culturally estranged governments – to buy the pictures from the Duke of Sutherland. They will appear in Edinburgh and London on a rotating basis, but have spent the first months of 2012 touring regional outposts. With a splash of water from the bathing Diana, the hunter Actaeon is turned into a deer: that is change as Ovid preferred it. But for Freud it was the splash of colour in Titian, the arranging of limbs, that counts for metamorphosis when it comes to the human form.

Did Freud actually like the body? Diana and Callisto is a celebration not only of beauty but of its price: Callisto, a favourite of the virgin Diana, is seduced by Jupiter, and the painting shows the humiliating moment when she is seen to be pregnant and is banished. All the women in the picture have a depth, a roundness and red-bloodedness, a variety of shade and tone, that makes them seem freshly alive.

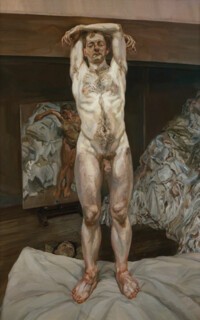

Against these favoured examples, Freud was a poet of the semi-recumbent dead or dying. His people could never blush. Death is the focus of the blockbuster show at the National Portrait Gallery (until 27 May): these fleshy phantoms stand or recline in a universe of putrefaction. The individual canvases are stunning, but when you see them all together, a sense of spiritual plague comes off them like a dead-handed signature, reminiscent of the sun-blotting visions that appeared before the Ancient Mariner:

Her skin was as white as leprosy

The Nightmare Life-in-Death was she

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

It seems to me that Freud in some way loathed human beauty. What interested him was corporeal sickness, the over-ripeness of obesity or the concave vacancies of emaciation; you can’t look at these bodies without wondering what ails them. These are worried portraits, riffs across the darkening plains of too, too solid flesh, and, by the final room, with heaps of paint barnacled onto so many images of suffering physicality, I was convinced that Freud had entered the world in order to squash the naturist tendency.

But the rooms show you that it wasn’t always so. Long before he was using paint as a blistering variant of flesh, the pictures had another sort of realism. The early 1940s portraits show square-headed and boss-eyed people, the lines of their jaws or eyebrows very clear and almost bracingly definite. But expression comes into them, an Otto Dix-like fixity of gaze, the figures often glassy-eyed and slightly green-faced, caught in the act of being. There’s still a touch of the pencil about these works: the shading is delicate and the people are fractured, but they are not yet disassembled by their own media. You can actually see Freud’s style morphing into itself. The 1950s portraits, Sleeping Nude (1950), for example, and Girl in a Green Dress (1954), are still drawn, sharply defined, thin on paint. The great coagulation begins in 1958 with Woman Smiling. The background is foggy and troubled and so is the skin: there’s now a difference to the way the paint is being used.

In this style, the one that stayed, the pictures are objects in which the mind appears to be made of paint, just as the ears and the lips and the sternum and the belly are paint. With time the painterliness of Freud’s portraits will come to obliterate the subjects. Content will be a manipulation of form, a swish of the brush, and the people in Freud’s paintings will be what the brush wants them to be. For more than forty years – from 1968 – every painting is compelled by a vision of flesh and paint as being essentially the same substance, redolent of weight and mass gone wrong, of solidity petrified. Leigh Bowery never looked as much like Leigh Bowery as he does in Freud’s paintings of him. Seeing them in one room at the National Portrait Gallery, you forget that this Blitz Club kid was once the prince of self-malleability. In the paintings, everything about him is pulled down by the weight of his own flesh. David Hockney doesn’t look so much like himself as like Freud’s style looking like itself: he is jowlier, his hair is more sparse, his eyes are pained, his brow is heavier, his collar is askew, his mouth is parched, his skin is mottled. While the portrait was being painted, David Dawson took a picture of Hockney next to it, with Freud coming in through the studio door. Hockney looks as though he is sitting beside an amazing snapshot of his inner dying self, his defeated archetype, caked in paint.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.