Beatification, which finally came to Thomas More in 1886, and canonisation, which had to wait until 1935, were only the icing on the commemorative cake. He had had, both during his life and since, a deserved measure of admiration as a scholar, a lawyer, a writer and a politician; for there is much in Robert Bolt’s adulatory A Man for All Seasons which reflects what we know of More. But More was not simply a principled Catholic; he was also something of a fanatic. The Victorian historian J.A. Froude described him as a merciless bigot. He described himself in his own epitaph as hereticis molestus. In ironic contrast to the religious toleration he described in Utopia, he advocated the execution of unrepentant heretics. ‘When all allowances are made for the rancour of his Protestant critics,’ the DNB says, ‘it must be admitted that he caused suspected heretics to be carried to his house at Chelsea on slender pretences, to be imprisoned in the porter’s lodge, and, when they failed to recant, to be racked in the Tower.’ He searched his friend John Petit’s house for heretical literature and left him in prison, untried. He applauded the burning of a harmless leather seller called John Tewkesbury, noting: ‘There never was a wretch, I wene, better worthy.’

And he was not, as it turned out, a man for quite all seasons. Henry VIII, whose faithful servant More professed to be and for the most part was, was a self-willed tyrant whose last resort against the papal refusal to sanction his divorce from Catherine of Aragon and his marriage to Anne Boleyn was to dethrone the pope as head of the church in England. In this he had the counsel of the ruthless and crafty Thomas Cromwell.

More had in 1529 accepted the chancellorship left vacant by the impeachment of his patron Cardinal Wolsey, on condition that he would not be expected to support the annulment of the king’s first marriage. He resigned the office in 1532 when the king succeeded in getting the clergy to acknowledge him as supreme head of the church in England ‘as far as the law of Christ allows’. Two years after that, a complaisant parliament passed the Act of Succession which required the king’s subjects, on demand, to swear acceptance of Henry and Anne’s progeny as heirs to the throne. It was More’s refusal, on religious grounds, to do this which led to his initial imprisonment in 1534. But the charge could only be misprision of treason, which was not a capital offence, and More resigned himself to a long stay in the Tower.

His undoing was the double-barrelled legislation that followed in November 1534. By the Act of Supremacy, Henry and his successors became – as the queen still is – ‘the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England’. And by a concomitant statute it was made high treason not only to plot physical harm to the monarch or his heirs but also ‘to deprive them of any of their dignity’. The act went on to make it treason to ‘publish and pronounce, by express writing or words, that the King our sovereign lord should be heretic, schismatic, tyrant, infidel, or usurper of the Crown’; but the indictment on which More was tried did not charge him with accusing Henry of heresy or schism, for he had been careful to keep his counsel about this. It charged him with seeking to deprive the monarch of his new dignity as head of the Church of England. This too was an offence requiring malice, and it is on this that much of the debate about More’s trial has for centuries turned.

More knew very well how he was being set up, and did what he could as a lawyer and as a theologian to evade it. Interrogated in the Tower in Cromwell’s presence in early May 1535, he was asked – according to the indictment – whether he accepted that Henry was now the earthly head of the English church, and replied: ‘I will not meddle with any such matters.’ A letter More wrote to his favourite daughter, Margaret Roper, confirms that he had said this, and that he had also said that he would not ‘dispute king’s titles nor pope’s, but the king’s true faithful subject I am and will be’. His response was charged as malicious silence. So too was his refusal to answer when interrogated again in June. But the record of this interrogation, which survives, shows More describing the Act of Supremacy as a two-edged sword: if he accepted that it was good law, it was dangerous to the soul; if he asserted that it was bad law, it meant death to the body. In saying even this much, More had arguably gone beyond silence: he had admitted that his conscience forbade him to acknowledge the validity of the act.

Much of the rest of the indictment was taken up with More’s correspondence with John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, also in the Tower awaiting trial and execution; but the letters had been burned and interrogation of More, Fisher and the Tower staff yielded little about their contents. The indictment also, however, asserted that More, in the course of an interrogation about the lost letters, had incriminated himself to the solicitor-general, Richard Rich. Urged by Rich to accept the new law, More had allegedly replied: ‘Your conscience will save you, and my conscience will save me.’ Rich had then, it seems, played the classic stool pigeon’s trick of disclaiming any authority to embark on the topic (today he would say ‘Off the record, Tom …’) before asking More directly whether, if parliament were to make Rich king, it would be treason to deny his kingship. More had replied that denial would be treason, since it would lie in his power to accept it. But if parliament were to enact that God should not be God, More then asked in response, would resistance be treason? Rich, accepting that ‘it is impossible to bring it about that God be not God’, responded with the real question: why should More not accept that the king had been lawfully constituted supreme head on earth of the English church? The cases are not alike, More was said to have replied, because a subject can consent to parliament’s making of a king, but not to its making of a primate. In other words, the conferment of supreme spiritual authority lay beyond the powers of a temporal legislature.

This, if truly said, was deadly. In Bolt’s play and in the eye of history it has become More’s nemesis; and what appears to be a contemporaneous longhand note of the conversation, corresponding closely with the indictment, survives in the National Archives. But the records of the trial, such as they are, give no hint that this part of the indictment was proved in evidence. The first account of its having featured in More’s trial is found in William Roper’s biography of his father-in-law, written some two decades later and at second hand. But while the Guildhall manuscript, which is the nearest we have to a verbatim report of the trial, contains no sign of Rich’s testimony, it is possible that Rich testified before the grand jury who found the indictment which set out his conversation with More to be a ‘true bill’ fit to go to trial. Thomas More’s Trial by Jury does not discuss this possibility, and since grand juries sat in private and may well have been able to indict without admissible testimony, it remains speculative. It is also distinctly possible that Roper simply took his account from the indictment.

What seems considerably less likely is the thesis which turned More scholarship upside down in 1964, when Duncan Derrett, in the face of much evidence to the contrary, suggested that the trial we know of was in fact a successful motion to quash the first three parts of the indictment, leaving the conversation with Rich as the sole basis for More’s trial and conviction. This account (advanced some four years after Bolt’s play) has a satisfactorily dramatic character, but Henry Ansgar Kelly, in his careful procedural review of the trial, is right to doubt it. Since Rich was solicitor-general, and may have been in court as part of the prosecution team, it is conceivable that a decision was taken to go for a conviction without using his testimony.

The present book, which is the work of many hands, includes a round-table discussion between three American judges and a British one about whether More had a fair trial. No one in the course of it mentions the nearest thing either country has had in modern times to a prosecution for withholding recognition of a questionable act of sovereignty: the contempt of Congress prosecutions brought against individuals who refused to answer the questions of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Here, as elsewhere, people may have been tried perfectly fairly for breach of an oppressive law. But one judge, the chief judge of the Fifth Circuit court of appeals, says of Rich’s account: ‘This cold record looks like “liar” to me.’ I am not so sure. Certainly there is an air of esprit d’escalier in the parting shot which, according to Roper, Rich put into More’s mouth: ‘No more could the parliament make the king supreme head of the church.’ But to say this was to say nothing that More had not already apparently said.

The problem with Thomas More scholarship, as this book illustrates, is that his defenders oscillate between arguing that he did nothing unlawful and was framed, and asserting that he died a martyr for his loyalty to the papacy. More, I suspect, was well ahead of them in this regard. He knew quite well that he was one of the principal targets of the Act of Treasons, which had actually delayed its requirements until 1 February 1535 to allow him and others to adjust their consciences, and that his only hope lay in silence. Cromwell and his other accusers knew this too, and the trial therefore became – and has remained – a forum for argument about the evidential significance of silence.

The right not to incriminate oneself was a longstanding doctrine of the canon law, much honoured in the breach when treason and heresy called for torture, not least under More’s own chancellorship. But there are numerous situations in which, without demanding that an accused person incriminate himself or herself, it is both lawful and reasonable to draw an inference from the fact that they have said nothing when one would expect them to say something. When in 1898 the law of England for the first time allowed accused persons to give evidence in their own defence, it also took away their privilege against self-incrimination once they entered the witness box. One of Michael Howard’s unobjectionable reforms as home secretary was to change the law, and the police caution corresponding with it, in order to warn suspects that, while they were not obliged to answer police questions, failure to do so might count against them at trial.

More’s silence, when faced with the simple question of whether he accepted the Act of Supremacy or not, was eloquent, as he knew it must be. One defence, a somewhat artificial one, was that, since silence can imply consent, he should be taken as having consented to the Act of Supremacy – something he believed to be a sin, as we know from Reginald Pole’s almost contemporaneous account of what More said once convicted: that the act was hostile to all law both human and divine. But his main defence was to fall back on the word ‘maliciously’ in the treason statute, arguing that there was no ill-will in his silence. As contributors to the book painstakingly explain, however, malice in law has for centuries been distinct from malice in fact. The latter signifies a requirement of ill-will, as it does frequently in libel. But used in criminal statutes it is ordinarily taken to mean ‘deliberately’, and that is the way it was read by the judges who sat to direct the jury who tried More.

The appendices to the book, which include the majority of primary sources for More’s trial, conclude with an attempt, using these sources, to reconstruct the trial in dramatic form. The reconstruction adopts Pole’s account that when the prosecutor urged that silence was itself proof of malice, the judges ‘even though no one had any charge to make … nevertheless all cried out together “Malice! Malice!”’ The docudrama accordingly has the judges at more or less arbitrary intervals croaking ‘Malice!’ It was without much doubt their ruling that malice required only intentionality and not ill-will that sent More to the scaffold for deliberately remaining silent. But it was earlier, in mid-June, when Fisher was awaiting execution and More still awaiting trial, that Cromwell had made a chilling note of things needing to be done:

Item to know [the king’s] pleasure touching Maister More and to declare the oppynyon of the Jugges theron & what shalbe the kynge pleasure.

Item when Maister Fissher shall go to execucion with also the other.

Send Letters To:

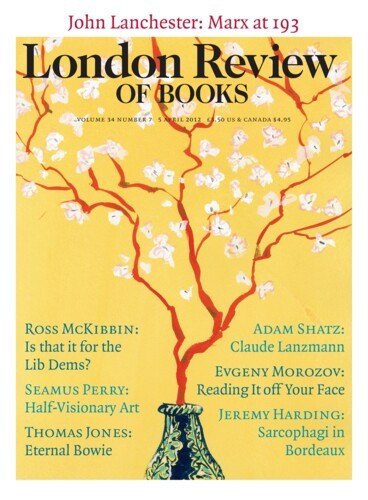

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.