Un Rat, las de la vie des villes, et des cours; (car il avait joué son rôle aux palais des rois et aux salons des grand seigneurs) un rat, que l’expérience avait rendu sage, enfin, un rat qui de courtisan était devenu philosophe, s’était retiré à sa maison de campagne (un trou dans le tronc d’un grand ormeau) où il vivait en ermite et dévouait tout son temps et tous ses soins à l’éducation de son fils unique.

Le jeune rat qui n’avait pas encore reçu de ces leçons sévères mais salutaires que donne l’expérience, était un peu étourdi; les sages conseils de son père lui semblaient ennuyeux; l’ombre et la tranquillité des bois, au lieu de calmer son esprit, le fatiguaient. Il s’impatientait de voyager et de voir le monde.

Un beau matin, il se levait de bonne heure, il fit un petit paquet de fromage et de grain, et sans mot dire à personne l’ingrat abandonna son père et le logis paternel et partit pour des pays inconnus.

D’abord tout lui parut charmant; les fleurs étaient d’une fraîcheur, les arbres d’une verdure qu’il n’avait jamais vues chez lui – et puis, il vit tant de merveilles; un animal avec une queue plus grande que son corps (c’était un écureuil) une petite bête qui portait sa maison sur son dos, (c’était un limaçon). Au bout de quelques heures il approcha une ferme, un odeur de cuisine l’attira, il entra dans la basse cour – là il vit une espèce d’oiseau gigantesque qui faisait un horrible bruit en marchant d’un air fier et orgueilleux. Or, cet oiseau était un dindon, mais notre rat le prit pour un monstre, et effrayé de son aspect, il s’enfuyait sur le champ.

Vers le soir il entra dans un bois, lassé et fatigué il s’assit au pied d’un arbre, il ouvrait son petit paquet, mangeait son souper, et se couchait.

S’éveillant avec l’alouette – il sentit ses membres engourdis de froid, son lit dur le faisait mal; alors il se souvenait de son père, l’ingrat rappellait les soins, et la tendresse du bon vieux rat, il formait des vaines résolutions pour l’avenir, mais c’était trop tard, le froid avait gelé son sang. L’Expérience fut pour lui une maîtresse austère, elle ne lui donna qu’une leçon et qu’une punition, c’étaient la mort.

Le lendemain un bucheron trouva le cadavre, il ne le regarda que comme un objet dégoutant et le poussa de son pied en passant, sans penser que là gisait le fils ingrat d’un tendre père.

A rat, weary of the life of cities, and of courts (for he had played his part in the palaces of kings and in the salons of great lords), a rat whom experience had made wise, in short, a rat who from a courtier had become a philosopher, had withdrawn to his country house (a hole in the trunk of a large young elm), where he lived as a hermit devoting all his time and care to the education of his only son.

The young rat, who had not yet received those severe but salutary lessons that experience gives, was a bit thoughtless; the wise counsels of his father seemed boring to him; the shade and tranquillity of the woods, instead of calming his mind, tired him. He grew impatient to travel and see the world.

One fine morning, he arose early, he made up a little packet of cheese and grains, and without saying a word to anyone, the ingrate abandoned his father and his paternal abode and departed for lands unknown.

At first all seemed charming to him; the flowers were of a freshness, the trees of a greenness that he had never seen at home – and then, he saw so many wonders: an animal with a tail larger than its body (it was a squirrel), a little creature that carried its house on its back (it was a snail). After several hours he approached a farm, the smell of cooking attracted him, he entered the farmyard – there he saw a kind of gigantic bird who was making a horrible noise as he marched with an air fierce and proud. Now, this bird was a turkey, but our rat took him for a monster, and frightened by his aspect, he immediately fled.

Towards evening, he entered a wood, weary and tired he sat down at the foot of a tree, he opened his little packet, ate his supper, and went to bed.

Waking with the lark he felt his limbs numbed by the cold, his hard bed hurt him; then he remembered his father, the ingrate recalled the care and tenderness of the good old rat, he formed vain resolutions for the future, but it was too late, the cold had frozen his blood. Experience was for him an austere mistress, she gave him but one lesson and one punishment; it was death.

The next day a woodcutter found the corpse, he saw it only as something disgusting – and pushed it with his foot in passing, without thinking that there lay the ungrateful son of a tender father.

*

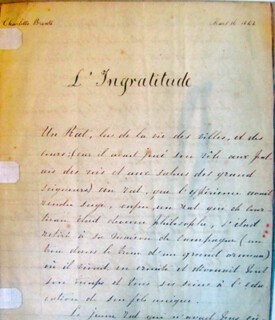

‘L’Ingratitude’ turned up in the course of my research for a biography of Constantin Heger, who taught Emily and Charlotte Brontë French during their time in Brussels and with whom Charlotte fell in love. I’d been trying to find out about his brother Vital, a sales representative for the royal carpet factory in Tournai and decided to look through the catalogue of the Musée royal de Mariemont for any mention of him – its eclectic holdings include carpets – and found a reference to a manuscript by Charlotte Brontë about a rat. It turned out to be the first piece of French homework Charlotte had written for Heger, lost since the First World War.

Early in February 1842, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, then aged 25 and 23, went to Brussels to board at the pensionnat run by Claire Zoë Parent on the long since demolished rue Isabelle. The sisters went to Belgium to complete their education, in the hope that they might one day open their own school back in Yorkshire. Parent’s husband, Constantin Heger, who taught at the nearby Athénée Royal, also taught French literature at the pensionnat. By all accounts a gifted and dedicated teacher, he gave Emily and Charlotte homework – devoirs – based on texts by the authors they had studied in class. They were to compose essays in French that echoed these models, and could choose their own subject matter: ‘I cannot tell on what subject your heart and mind have been excited. I must leave that to you,’ Heger told them, as he told Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte’s first biographer, after Charlotte’s death. Heger encouraged the Brontës’ writing, but demanded that they pay attention to their craft. ‘Poet or not … study form,’ he once admonished Charlotte. He often returned their essays drastically revised – sadly, there are no comments on this copy of ‘L’Ingratitude’.

It was finished a month after Charlotte arrived in Brussels and is the first known devoir of thirty the sisters would write for Heger. It contains a number of mistakes, mainly misspellings and incorrect tenses: the adjective ‘grand’ before ‘seigneurs’ should carry an ‘s’; ‘un odeur’ should be ‘une odeur’; several verbs are in the imperfect, e.g. ‘levait’, when they should be in the simple past, ‘leva’. Heger told Gaskell that when the sisters came to the pensionnat, they didn’t know any French. This wasn’t quite true, but Charlotte’s improved immensely during her time in Brussels.

‘L’Ingratitude’ might well be based on La Fontaine and J.P. Florian. Heger had his pupils at the Athénée Royal study both writers and probably used a similar curriculum at the pensionnat. Later they would study more complex writers such as Chateaubriand, Bossuet and Hugo. La Fontaine’s ‘Le Rat qui s’est retiré du monde’ is somewhere behind ‘L’Ingratitude’ – Charlotte even borrows some of its vocabulary. Florian’s fable ‘La Carpe et les carpillons’, about disobedient and thoughtless children, may also have come into it.

The sisters’ studies at the pensionnat ended abruptly in November 1842, when they returned to Haworth on hearing that their Aunt Branwell had died. In January 1843, Charlotte went back to Brussels, without Emily, to become an English teacher at the pensionnat. By now, she was deeply in love with Heger: ‘I returned to Brussels … prompted by what then seemed an irresistible impulse,’ Charlotte wrote to Ellen Nussey in October 1846. At the time of her initial arrival in Brussels, Heger was by all accounts happily married with three children. Two more children were born while Charlotte and Emily were there. Charlotte left Brussels for ever on 1 January 1844, worn out by her infatuation with Heger, and his wife’s hostility towards her. Back at home, she longed to see him again. In 1844 and 1845, she wrote him a series of letters (in French):

Day or night I find neither rest nor peace – if I sleep I have tormenting dreams in which I see you always severe, always saturnine and angry with me … I would not know what to do with a whole and complete friendship – I am not accustomed to it – but you showed a little interest in me when I was your pupil in Brussels – and I cling to the preservation of this little interest – I cling to it as I would cling on to life.

Heger replied to some of her letters, though his replies have never been found. At some point in 1845, he stopped answering. Charlotte’s novel Villette, published in 1853, reworks her experiences in Brussels, with the difference that the teacher returns the heroine’s love – Brontë kills him off at the end of the book.

In June 1913, Paul Heger donated the four surviving letters Charlotte wrote to his father to the British Museum, and gave permission for them to be published in the Times. The publication caused a sensation and drew the attention of one of Belgium’s most avid art collectors, Raoul Warocqué. Warocqué’s family had made a fortune from coalmining. In 1829, they bought the ancient royal hunting grounds of Mariemont, where they built a castle surrounded by parkland. Raoul was said to be the wealthiest man in Belgium, if not Europe; a banquet at Mariemont in 1903 was attended by more than three thousand guests, including the future king of the Belgians. An occasional diplomat for Leopold II, Warocqué used his travels around Europe, Russia, India and China to acquire numerous treasures for Mariemont. They included a five-ton ‘fragment’ of a sculpture of a Ptolemaic queen and a Bourgeois de Calais by Rodin. He had no heir; and the collections, castle and grounds were left to the state. In 1960, a fire destroyed the castle but the collections were saved; a new museum opened in 1975.

Warocqué also collected manuscripts and after reading Charlotte’s letters in the Times decided he wanted to add her to his collection. He knew Paul Heger, the rector of Brussels University, because he’d paid for the university’s anatomy institute in 1891. Warocqué wrote to Heger, saying he hoped to acquire one of Charlotte’s letters. In August 1913 Heger replied: ‘We don’t have any of Charlotte or Emily’s letters any more, but I could possibly get hold of another souvenir of their Brussels stay.’ In November, Heger wrote again: ‘I hope to be able to please you; when we get a chance to meet I will tell you why there is a delay.’ Six months later, Heger was insisting he hadn’t forgotten: ‘If I have not already sent it to you, it is because I would like to “situate” it in a way that you will find pleasing. Now there’s a sentence that will intrigue you; I won’t say any more about it so I can prepare a little surprise for you.’

Warocqué received his gift the following year. It was a small grey album inscribed with his name, its two dozen pages filled with facsimiles of Charlotte’s four letters to Heger, photographs of the pensionnat and the manuscript of ‘L’Ingratitude’.

Brian Bracken

The translation is by Sue Lonoff.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.