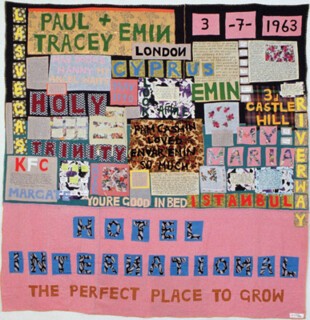

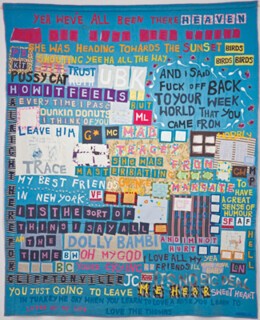

Quilts used to be made from baskets of scraps; old clothes were cut up, the worn and stained bits discarded, the best parts kept for reuse. Every household where a woman lived had such a container – a midden of memories – and when the scraps had become a patchwork quilt, spotting this old dress or that old pair of curtains or that old cushion was part of the pleasure of the bed, a domestic pleasure. The quilt became history, the equivalent of an itinerant storyteller’s painted roll. The classic patterns were abstract and geometric, but sometimes the form moved closer to the sampler and included words and stories. Tracey Emin’s blankets, which blaze from the walls of the first room of her exhibition, Love Is What You Want, at the Hayward (until 29 August), declare themselves defiantly to belong to this homemade tradition of female hands and eyes. The earliest here were made in 1993-99 and present her own furious portrait of the artist as a young woman. A gaudy jumble of colours and scripts, with cut-out wonky capitals, salvaged and embroidered emblems, and patched pieces of journals and private messages, these are powerful works, assembled at the slow speed of handicraft to communicate cris de coeur, outbursts of passion and protest. The quilts are banners unfurled with irrepressible energy, and their deliberate amateurishness and gypsy excess intensify the feeling of honesty and spontaneity.

A more recent quilt, from 2005, hangs upstairs, and is blanched, a study in cream and white. It always Hurts is the title. The gypsy festiveness has been quelled, and the anger has turned to sorrow. The final rooms are filled with smeary white paintings, closer to De Kooning and Twombly than anything Emin has done before, and reveal the artist in a state of mourning for lost time: on the balcony of the Hayward, she’s placed bronze casts of a tiny teddy bear, and a single toddler’s shoe and sock. The child might be one of her terminated conceptions, but it’s more probable that it’s her former self. The poignancy works – just – because she has plunged us so deeply into her story, into her soul (a term she uses without irony). She does manage to hold her work this side of mawkishness and self-pity, and when she needs to, refines her skill to control the sensationalism.M

The best drawings in the show have been montaged into a flicker film, Those who suffer love (2009), showing a woman zestfully – or is it frantically? – arousing herself. We assume it’s Emin because her art is so autobiographical, but these are very unusual self-portraits, in that she couldn’t pose for them (no possible mirror angles here). They’re drawings made in the mind, and have nothing to do with the languorous spectacle of Ingres or Klimt’s self-pleasuring odalisques. They’re charged with a furious erotic longing, and in Francis Bacon’s terms, they go straight past the brain to the nervous system. Self-revelation is an art, and public intimacy – to use Giuliana Bruno’s phrase – requires crafty selection, decisions and deceptions.

The American artist Kiki Smith is one of the women artist storytellers who ‘thinks with her body’ – as Emin learned to do, she tells us in her odd and powerful memoir Strangeland (2005), while growing up in Margate (the title of the book picks up on the resort’s once famous attraction, Dreamland). Smith, too, cuts and sews and records events in her life, her passage through love and grief; she must be one of the artists Emin has looked at carefully. Smith recently made a series of works inspired by Prudence Punderson’s First, Second and Last Scenes of Mortality, embroidered in New England in 1780, which shows the three stages of woman, with a cradle, a bed and a coffin (a black maid holds the baby). Emin is a chronicler of women’s rites of passage, and for all the haunting presence/absence of men in her work, she conveys truly passionate attachments to women. In that first blanket, Hotel International (the name of her father’s Margate enterprise), the embroidered words ‘My Maria’ invoke a girls’ alliance and a sense of anguished loss at the end of the friendship. The larks she had with another bad-girl artist, Sarah Lucas, still radiate girl power, and the grandmother whom she called ‘Plum’ and who called her ‘Pudding’, fills her memories of growing up with genuine lovingness.

She sought out Louise Bourgeois towards the very end of Bourgeois’s long life, and their collaboration was only natural, really: Emin was placing herself in the older artist’s lineage because she too works with formerly despised handicrafts to communicate her feelings as events and her self as a sexed body. But unlike Bourgeois, who returned again and again to her father’s affair with her governess, and staged a cannibal banquet at which he was ritually eaten, Emin is tender about her father, who died last year. She uses his name, though her mother and he never married. He seems to have passed on to his daughter her untoward honesty, even confiding in her about his sex life. She mentions with a kind of pride that he had lots of children – ‘ten that I know of’ – and reports his telling her that old women never go to heaven because Muhammad turns them into angels first, young and beautiful. Cyprus and Turkishness matter to her. In the video Emin & Emin, he’s heard singing a lullaby in Turkish over a video in which he can’t keep on his feet in the Cypriot surf – while Tracey herself, a modern Aphrodite, strikes out smiling. ‘I love you, Daddy,’ we hear her say.

There are long gaps in the story unfolded by these works. Someone, somewhere, at some point, must have noticed the young truant with the lopsided smile and the haphazard spelling, and helped her on her way to the Royal College of Art. Perhaps she has spoken or written about the transition, but it is not part of her artistic persona. The way we are told her life so far has elements of a diva’s biopic about it. Like Piaf, Emin is a guttersnipe; she trailed around the seedy seafront at Margate, was raped at 13, lost her front teeth in a fight and was exploited by (impotent) boys and sleazy photographers. Her mother scavenged lead from abandoned houses, and after Hotel International failed and her father left, the family lived in a council flat above a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet. The story is gripping and appalling, and there is much more in the same vein. But she is indomitable, she is fortune’s child, carried to fame by her gifts, her jolie-laide charm, her naive expressiveness and emotional sincerity, her transparent love of the money and gorgeous clothes which success has brought her way. She shares many features with other idols – Colette and Callas, Garland, and even Monroe.

I am not proposing that Emin has shaped her tale consciously to fit modern myths. Not at all. But it is one of the reasons her art has caught the popular imagination so powerfully. It is also the reason her audience defends her. She has so completely presented herself as a poor, artless, damaged child, as a woman under the influence and as an outrageous and disruptive grande dame, that her admirers and her critics defensively assert her proficiency, her art historical references, her authenticity as an artist as well as a media personality. But the way her art tells her story can be looked at in another way, placed in a literary lineage running back to Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf and Anaïs Nin. In Self-Impression, his remarkable study of Victorian and Edwardian autobiography, Max Saunders discusses the vogue for fake memoirs, a genre he calls ‘autobiografiction’, that is books in which the ‘I’ is an adopted alter ego, performed with complete convincingness.* Saunders is interested in the way people romance themselves into another persona, and then give this ‘imaginary friend’ a complete life story. Such works are fiction under another name, heirs to such earlier romance memoirs and traveller’s tales as Robert Paltock’s The Adventures of Peter Wilkins, the memoirs of the Comtesse d’Aulnoy and the better-known Moll Flanders and Tristram Shandy. But Saunders’s readings lucidly reveal the origins of the continuing, ever growing eagerness of audiences to feel that what they are experiencing has not been made up and they are not being taken in. To appear to be confessing, not inventing, has become a necessary ingredient of a successful work of art. Tracey Emin the artist is the imaginary friend of Emin the life-writer.

Saunders’s self-impressionists, veracious and subtle (Proust, Woolf), ventriloquists and counterfeiters (‘Mark Rutherford’, the pseudonym used by William Hale White, and, you could add, Edward FitzGerald), foreshadow current developments in autofiction, in which memory acts become, as the filmmaker Chris Marker put it, ‘the lining of forgetting’, where ‘lining’ renders the French doublure, with an echo of doppelgänger.

Everything lies in the choice of the pieces of fabric used because what is picked out will determine the shape of the tale. Virginia Woolf, whose presence haunts these autobiografictional developments, wrote a heartfelt declaration in which she evokes this process:

It is only by putting it into words that I make it whole; this wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me; it gives me, perhaps because by doing so I take away the pain, a great delight to put the severed parts together … From this I reach what I might call a philosophy; at any rate it is a constant idea of mine; that behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern; that we – I mean all human beings – are connected with this; that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of the work of art … We are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself. And I see this when I have a shock.

Different patterns take shape in the cotton wool, formed by the individual artist’s cast of mind: Bourgeois, for example, had a lifelong engagement with mythical symbolism, which she encountered first in the tapestry workshop of her parents, and later in the ethnographic, art historical milieu of New York in the 1940s. Her imagery works with ideas of incarnation – often sacrificial – in a strongly flavoured mixture of pagan-Judaeo-Christian-Freudian symbols. By contrast, the Jungian ambience of Meret Oppenheim’s native Zurich provided the impulse for her works expressing her lot as a woman: such marvellous, mischievous pieces as the famous fur cup and saucer (Petit déjeuner en fourrure) and the dish of white stiletto shoes upended to become frilled cutlets (Ma Gouvernante, My Nurse,Mein Kindermädchen). Oppenheim worked in every medium, and kept a dream journal of drawings and memories. Born in 1913, she was two years younger than Bourgeois, but died long before her, in 1985; for this reason she has perhaps not been sufficiently recognised as one of the crucial foremothers of Emin’s generation.

For Emin, the pattern in the cloth (in the cotton wool) is formed by the sexuality of the female body as explored in postwar feminism: ‘fecundity’ is a word she often uses in her work. Once her sexual encounters filled her images, but her recent work is suffused with the children she hasn’t had. Not having had a baby concerned her long before she reached an age that made it unlikely that she would ever have one. Generative as an artist and a public hoarder (so many different media, such accumulations of memorabilia), she chronicled her abortions, particularly one that went badly wrong. This piece, How it feels (1996), is a 22-minute confessional film, in which Emin returns to the sites of the experience, including the hospital, the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, named after one of the most courageous doctors to put women’s bodies at the centre of her concerns (it has since been pulled down to make way for apartments behind Unison’s grand new building on the Euston Road).

Emin is very good at capturing emotional contradictions, the wanting not to have a child and the wanting to be the kind of person who could have one; she invites identification from her viewers, and gets it. Women feel she speaks for them (they come up to her and thank her for talking of her longings, her losses, her unrequited passions, her endless sense of unfulfilment). She speaks like the indiscreet jewels of Diderot’s novel, in which the sultan finds out his wives’ private thoughts using a magic ring a djinn has created for him. What the sultan hears startles him: these women have independent minds but keep them hidden.

Les Bijoux indiscrets used to be considered a pornographic galanterie of the Enlightenment, and Diderot himself, when he became a great philosopher, seems to have retracted it. But the novel’s loquacious voices, speaking of women’s bodies in uncompromising terms, are now seen as proto-feminist, altogether in accord with Diderot’s emancipated views of women’s potential. Emin’s speaking jewels inspire the novelist Ali Smith, in a contribution to the exhibition catalogue, to rhapsodise, especially about Emin’s drawing A cunt is a rose is a cunt. She quotes Gertrude Stein to illuminate Emin’s way of infusing banal everyday stuff with eroticism: ‘What did I do?’ Stein asked about words, ‘I caressed completely caressed and addressed a noun.’ In The Art of Tracey Emin (2002), a collection of essays edited by Mandy Merck and Chris Townsend, art theorists salute her as a pioneer, many claiming her for the feminist vanguard. Some of the works in this huge mid-career retrospective are lesser than others, and show the call of commerce (the neon slogans, for example). But in sum Love Is What You Want pulls you into the artist’s personal vision as into a powerful memoir, and the lasting impression is touching and oddly winning. You (I) can’t help but admire the way Tracey Emin lays bare her heart, and much else besides.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.