His lips with joy they burr at you,

But, Betty! what has he to do

With stirrup, saddle, or with rein?

Wordsworth, ‘The Idiot Boy’

Like most people who live in cities I’ve had occasional street encounters with lunatics – none of them (the encounters) exactly Wordsworthian. There was the man with Tourette’s, whimpering, on the bus in Minneapolis – head and neck appallingly bruised, face abraded and blood-caked, thanks to the compulsive smacks and scratches he seemed unable to cease giving himself every few seconds. There was the wacked-out lady in Toronto who, as a friend and I trudged down snowy Bloor Street, abruptly wiggled out of every flimsy article of clothing she was wearing and lunged at us, nude and flailing and shrieking, in menacing fashion. Less violent, but no less eerie, was a teenage girl with Down’s syndrome who suddenly lolloped up to me on a sidewalk in Tacoma, Washington – I being then a morose and moony college student – and kissed me on the cheek. For weeks I wondered if her gesture was a sign from the cosmos that I was going crazy. Now I’m not sure it meant anything.

Such incidents, disconcerting at the very least, have come to mind often recently in connection with my latest intellectual obsession – the gorgeous, disorienting, sometimes repellent phenomenon known as outsider art. It may be that anything in which one becomes absorbed produces its ready share of ambivalence: that objects of fixation trouble as much as they arouse. Certainly, that would seem to be true in my case. Strange fits of passion have I known – a carload of them – but few that have not involved mixed feelings. Yet even for me, the love-hate feeling that outsider art elicits is peculiarly intense.

I’ve been collecting the stuff, fairly omnivorously, the past five or six years, but always with self-doubt and a certain ethical uneasiness. Go away a little closer, Idiot Boy. I’ve got all the recent books on the subject. But reading books – and there have been droves over the past decade – seems only to deepen the confusion. Witness Create, a glossy catalogue published to coincide with a major show of Outsider Art at the Berkeley Art Museum this spring. However beautifully put together, the book unsettles, not least by its thoroughly hip-bourgeois and neatly packaged aspect. It’s a sort of indie-trendy, iPhone-Android-Compatible, Meeting with Remarkable Lunatics.

First things first. What is outsider art? The name itself turns out to be controversial. The definition proffered by the great god Wiki, at whose altar we now all worship, happens to be quite brilliantly concise and to the point here:

The term ‘outsider art’ was coined by the art critic Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English synonym for ‘art brut’ (‘raw art’ or ‘rough art’), a label created by the French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the boundaries of official culture; Dubuffet focused particularly on art by insane-asylum inmates. While Dubuffet’s term is quite specific, the English term ‘outsider art’ is often applied more broadly, to include certain self-taught or naive-art makers who were never institutionalised. Typically, those labelled as outsider artists have little or no contact with the mainstream art world or art institutions. In many cases, their work is discovered only after their deaths. Often, outsider art illustrates extreme mental states, unconventional ideas, or elaborate fantasy worlds.

Yet the proliferating cross-linguistic nomenclature also suggests the difficulty critics have had making sense of the phenomenon either anthropologically or aesthetically. Thus: art brut, ‘raw art’, ‘naive art’; the art of the ‘self-taught’, the art of the ‘untrained’; art by those outside the mainstream art world; art by the institutionalised; but also, confusingly, art by some of the non-institutionalised – a group one might call the non-institutionalised-but-nonetheless-very-strange. The Wiki authors seem here to be thinking of, among others, Henry Darger, the obsessive, reclusive, quasi-paedophilic Chicago hospital janitor and bona fide outsider-genius, who died in 1973, leaving behind hundreds of extraordinary scrolls of artwork, exquisitely painted and collaged, depicting an apocalyptic conflict, Homeric in scope, between the Vivian Girls (heroic little girls, often shown naked and with tiny penises) and evil male marauders on horseback known as Glandelinians.

To this panoply of possible terms one might add ‘visionary’ or ‘intuitive’ art, ‘art from the margins’, ‘unofficial art’ and so on. Several long-established art-historical labels – folk art, vernacular art, popular art – would likewise seem to have some relevance. And judging by its urban San Francisco incarnation, the one I know best, outsider art has recently developed some fascinating semantic and subcultural connections with what is known locally as ‘alternative’, ‘urban primitive’ or ‘indie’ arts and crafts – the punk-surreal world of Etsy.com (yarn-bombed furniture, Duchampian hats made out of toilet plungers, bubble-wrap mittens and the like). The pre-eminent San Francisco gallery space for outsider art, Creativity Explored, is located in the Mission district, the heart of the city’s edgy skateboard-graffiti-artist-mural scene (Shepard Fairey and André the Giant’s stomping ground), and stands next door to a bustling little zine-selling, freaky-crafts emporium known as Needles and Pens, inevitably staffed by heavily tattooed, formerly middle-class young people with nose rings and huge (surely painful?) metal disks and Bantu bangles lodged in their earlobes.

Despite this cluster of interrelated terms, I have to say that I think Dubuffet, originator of the art brut label, had the conceptual emphasis right: outsider art is best defined as art produced by those, who if not officially classed as ‘insane’ or institutionalised, are in some way mentally or socially estranged from, well … the rest of us. Yes, to speak colloquially, I mean the mad – the nutty, the unhinged, the non compos mentis, the permanently unresponsive, the people known, more politely, as having psychological ‘deficits’. A definition that excludes the element of mental alienation fails to get at something central in the phenomenon.

Thus the term ‘folk art’ has never seemed in my mind a particularly accurate translation of outsider art for the simple reason that the objects conventionally described and marketed as folk art have generally been produced by apparently rational beings fully integrated into their (usually settled and rural) communities. However imaginatively fashioned, such artefacts usually served some homely practical function; indeed, the stereotypical folk art object, one might argue, is always made with some useful purpose in view.

At least in my own mind, the term ‘folk art’ conveys an idea of polish, clarity and finished smoothness – a kind of neatness and respectability – aesthetically foreign to the sometimes violent derelictions of the outsider mode. Many so-called folk art objects, having been heavily restored and repackaged – cleaned up, framed or remounted – become sanitised in the process: made twee and dull and precious-seeming. They lack for the most part those unnerving intimations of entropy and menace and disaster – of failed psychic hygiene, metaphysical anxiety and disquieting fanaticism – present in so many outsider artefacts.

Other labels displease for related reasons. When applied to outsider figures like Henry Darger, descriptors such as ‘self-taught’ or ‘untrained’ seem at once too fast and loose and more than a little euphemistic and sentimental. Fast and loose because they risk opening up the potential ‘canon’ of outsider art, somewhat comically, to artistically unschooled violon d’Ingres types like D.H. Lawrence, Arnold Schoenberg, Winston Churchill and Prince Charles – talented amateur painters, possibly, but not exactly what you would call marginal or psychically alienated figures. Euphemistic, in turn, because once again the sheer intransigence of outsider art – its blankness, nihilism, incommunicativeness, what you might call its autism, the refusal or inability of the artist to follow normative social and psychological codes – is soft-pedalled. What makes Darger, as a creative consciousness, different from Lawrence, Schoenberg and the like is precisely what challenges understanding.

Where do I get such tendentious opinions? No doubt in part from some early curiosity about ‘madness’ – what it was, and how it showed itself (if indeed it did) in works of art. My present preoccupation with outsider art looks now to me to have been inevitable: the coming to fruition of a somewhat morbid childhood interest in visual strangeness and its producers. A very early preoccupation of mine I recall (I was five or six) were the hallucinatory paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, reproductions of which I’d come across, along with Picasso’s disquieting Minotaurs, in a paperback history of European art my mother owned. The Garden of Earthly Delights I never tired of, crazy-looking though it was. The weird punishments visited on the sinners in Hell were riveting enough, but even freakier, possibly, were the pleasures to be found in Bosch’s world – the surreal salamander-bliss depicted in the eponymous Garden and beyond. Strangest of all: the fact that outlandish things were happening – all over the painting – but that nobody, even in hell, looked to be particularly tormented. Indeed, some of the little naked human figures seemed to display a near comical sangfroid, even as they were pecked by giant birds, hatched out of eggs, had huge flowers inserted in their bottoms, or, in the case of one of my favourites, sported a monstrous blueberry instead of a head. What sort of person could have dreamed this up?

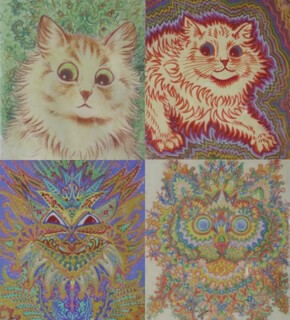

My interest in such bizarrerie only intensified over the years. Thanks to an artistic mother I’d grown up with a precocious liking for post-impressionism, modern art and especially surrealism: Klee, Calder, Bacon and Salvador Dalí were all icons in this junior-varsity phase. But I remember being mesmerised, too, by a short documentary I saw in high school about art made by schizophrenics. (This would have been in the late 1960s, the heyday of R.D. Laing’s radical anti-psychiatry movement.) Most gripping were the magnificently demented illustrations of Louis Wain (1860-1939), a hugely popular British artist who after a successful international career as an illustrator and cartoonist, spent the last ten years of his life in an asylum near St Albans. Wain specialised in comic illustrations of cats, and scores of his cat postcards, cartoons and children’s books can still be found.

Like Degas or Mary Cassatt, Wain could draw a perfectly normal-looking cat when he wanted to – at least for a while. But over time the anthropomorphised expressions become more and more intense, bug-eyed and oddly sinister (notably when the feline subject is shown smiling). Colours and backgrounds gradually turn more febrile and abstract. Late 19th-century ‘mad-wallpaper’ backgrounds proliferate. And especially when rendering Persians and Angoras and other long-haired breeds, Wain begins to show his cats with fur brushed up, as if full of static electricity. The effect is often so marked that in some images the pointed tufts of fur surrounding the cat’s body make a kind of jagged, phantasmagoric aura that fills up or overwhelms the picture space. In the psychedelic sequence below, one can see this development taking place in an almost stop-action way:

Once the quintessential (if eccentric) insider, Wain seems here to metamorphose into an outsider – which is to say, a lost soul – before our very eyes.

Wain’s valedictory works illustrate a characteristic many contemporary outsider artists share: an aversion to blank space: a horror vacui and a manic compulsion to fill every inch of the available paper or canvas with some kind of colouring or mark. Seeing pictures by Wain no doubt prepared me for this obsessive mark-making: the worked-over supports, the tendency to hypnotic patterning and the distorted and ambiguous figure-ground relationships one finds in an important strand of outsider art. You might call Wain’s ‘mad’ style a version of the outsider mode in its paranoid or maximalist aspect. It’s as if one needs protection and this protection is best achieved by filling in the image to absolute repletion. Obviously the creation of such imagery takes a great deal of time and requires thousands of small repetitive actions with brush or pencil or tool. Yet one can imagine how such a practice might serve a victim of mental agitation as a form of superstitious magic, as self-soothing or self-medication.

Which isn’t to say that some gifted outsider artists don’t have the opposite tendency. Some, like the contemporary San Francisco artist Jimmy Miles, incline to a dry, coolly minimalist practice, in which white space is not only tolerated, but an essential, if seriously off-kilter aesthetic feature in its own right:

I’m not sure what to call Miles’s austere and evacuated style. Some kind of Blakean radical simplicity? A borderline personality’s childlike satisfaction in the diagrammatic or toothpick-like? A predilection for imagining oneself tiny, generic and off-centre? Miles shows little in the way of Wain-like ‘white space’ paranoia. Yet do such stylistic differences matter when it comes to the emotional responses elicited in a viewer? Whether symptomatic of fear or vacancy – some roiling tumult in the brain or its zen-like emptying out – the outsider image invariably takes us to its own lonely, offhand, bewildering place, one to which, in the end, we may feel we have only the skimpiest psychic access.

In the 1980s and 1990s my own predilection for outsider art coincided with a growing awareness of the phenomenon in American culture at large. In Continental Europe, where, thanks to the advocacy of Dubuffet, Breton and others, the links between outsider art, abstraction and the aesthetics of the avant garde had been noted early on, the discussion was already fairly well advanced. In 1921 the Swiss doctor Walter Morgenthaler published A Psychiatric Patient as Artist, about the case of Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930), a Swiss psychotic subject to terrifying hallucinations, who was incarcerated at the Waldau Clinic – a mental asylum – in 1895 for sex crimes. Once sequestered, much of the time in solitary confinement, Wölfli spent the rest of his life obsessively making drawings – bejewelled, fantastical and arcane ones, sometimes containing his own odd musical notations – using coloured pencils and paper donated by the doctor and his colleagues.

Wölfli has never hugely appealed to me, but it’s worth pointing out that outsider artwork like his – microscopic in orientation, full of almost cellular, eye-straining detail and crammed with minuscule numbers, musical notes and scrawled pieces of text – doesn’t reproduce well. Until very recently, the work of outsider artists has often shown up poorly in books and museum catalogues. The same deficiency is noticeable, alas, in the blurry and unsatisfactory images one sometimes finds in Raw Vision – now the most prominent contemporary publication devoted to outsider art. It wasn’t until the Wölfli retrospective at the American Folk Art Museum in 2003 that I developed a finer purchase on his amazingly intricate but decidedly sociopathic world.

In the 1990s and early 2000s several outsider artists were ‘discovered’ in the US and fêted with important exhibitions. Until then, the mainstream art world had generally viewed outsider art with distaste or ignored it entirely. Yet thanks to burgeoning popular interest in ‘alternative’ visual phenomena of all kinds – vintage styles, kitsch, graffiti, zine culture, handmade objects – and a certain postmodernist ‘deskilling’, the aesthetic status of outsider works began to rise. Shows of artefacts by self-taught artists began to take place in major museums and galleries; dealers sprang up to capitalise on the new popular interest. The New York Outsider Art Fair was established in 1993, and grows bigger every year.*

Among the first of these discoveries – and still perhaps my favourite outsider figure – was A.G. Rizzoli (1896-1981), a shy San Francisco architectural draughtsman, who lived with his mother until her death (they shared a bedroom) and, it is said, ‘died a virgin’. His work consists of astonishingly detailed drawings of lofty, airy, cathedral-like Beaux Arts fantasy buildings. Each of these imaginary temples was conceived as a ‘symbolic representation’ of a specific human being and signified the artist’s veneration of the person thus commemorated. Among the human subjects Rizzoli transmogrified thus were his mother, certain family friends, the odd San Francisco civic leader and a little girl named Shirley Jean Bersie who lived in the artist’s Potrero Hill neighbourhood and liked to visit him and watch him draw.

Most of Rizzoli’s drawings include captions and other pieces of text, invariably rendered in beautiful hand-drawn lettering reminiscent of early 20th-century municipal signage and Fancy Printing. Rizzoli liked to make his otherwise ethereal images look ‘official’: the early ones often bear a little corporate-looking emblem or artist’s logo with the initials A.T.E., meaning (according to Rizzoli, whose first name was Achilles) Achilles Tectonic Exhibit. Later he introduced another municipal-sounding acronym into his images – Y.T.T.E, which stood for Yield to Total Elation. Indeed, for an outsider artist, Rizzoli at times displays unusual tenderness and wit, qualities that on occasion almost morph into sociability. Combined with the gorgeous architecture, the result is often jazzy and exquisite, even sublime:

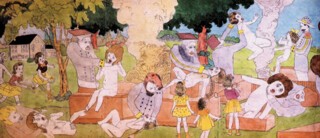

Though Henry Darger’s creative work had been known (by his neighbours at least) since just before his death in 1973, and was safely extracted from the squalid junk piled up in his tiny Chicago apartment when he died, he, too – orphan, recluse, janitor and visionary creator on an epic scale, the Michelangelo, if you like, of outsider art – might likewise be considered a discovery of the 1990s. The first big show of his work I saw was in 1996; in 1999, John Ashbery published a book-length poem entitled Girls on the Run, the cover of which bore an arresting Darger watercolour showing some of the Vivian Girls in panic-stricken flight. The ‘literariness’ and epic ‘virtual world’ quality of Darger’s work – effects intensified by his use of tracings and collage, hand-scrawled text, obsessive storylines and comic-strip elements – have made him particularly fascinating to writers. He might even be called an outsider writer as well as outsider artist. Along with the long, panoramic, doubled-sided scrolls depicting the Vivian Girls’ struggle against the barbaric Glandelinians, Darger also left behind almost 20,000 pages of autobiographical writing and texts relating to the melodramatic incidents he had illustrated.

It must be acknowledged that the now global recognition his work has received (he was recently the subject of an elegantly massive catalogue raisonné edited by a curator at the Museum of Modern Art) has no doubt to do with his works’ noirish mixture of extraordinary artistic delicacy and ultra-creepy subject matter – of visual loveliness and sensationally grisly scenes of violence and perversion. Once seen, his pale, shockingly uncensored pictures are never forgotten. He was clearly fixated on macabre themes involving girl-children: witness the multiple gory images in his work depicting mutilation, evisceration, fires and explosions, executions, and in particular, death by strangulation or throttling – the punishment of choice visited on the rebellious Vivian Girls by their brutal Glandelinian persecutors.

Yet Darger is also one of the most subtle and enchanting colourists in the history of figurative art. Even his most horrific images are rendered with an almost preternaturally refined palette – in greeny blues, black and pale yellow, with tints of flame-red. At times the handling of the watercolour can be Sargent-like. One feels almost ashamed for noticing such strange and compromised beauty, but one does.

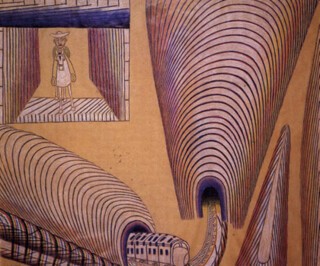

Over the past ten or 15 years numerous outsider artists have been similarly canonised, but some kind of critical milestone was reached four or five years ago with the rediscovery of Martín Ramírez (1895-1963), an indigent Mexican labourer who came to California for work in 1925, and ended up in a succession of psychiatric hospitals. A catatonic schizophrenic (after a certain point he seems never to have spoken or responded to language again), he drew constantly, producing large, hypnotic images on brown paper bags or donated rolls of examining-table paper of the type you see in doctors’ surgeries. His characteristic subjects include arid Mexican landscapes and hills (often with train tunnels and trains coming through them), horse-riders, deer and madonnas.

The critical milestone to which I refer was an exhilarating, even rhapsodic review of the 2007 exhibition of his work at the American Folk Art Museum, in which Roberta Smith, senior art critic at the New York Times, declared Ramírez ‘one of the greatest artists of the 20th century’.

Ramírez had an indelible style built on a supreme sense of economy and shot through with a mix of sly humour and sunny optimism that coats deeper, darker feelings. He had his own way with materials and colour – buoyed by an unerring sensitivity to the power of blank paper – and a cast of unforgettable characters, including mounted caballeros, levitating madonnas, and deer and dogs on high alert. But most of all Ramírez had his own brand of pictorial space, which he regulated with rhythmic systems of parallel lines, curved and straight. He played spatial illusion as if it were an accordion, expanding and contracting it in a mesmerising alternation of stasis and movement.

If such a paean represents a contemporary art-world legitimation (however belated) that one would be hard-pressed to beat, it is also thrilling, because one can’t help but feel Smith was right.

All to the good – this ongoing cultural validation of outsider artists. So what, then, is my outsider art ‘problem’? Whence the unease? The push-pull, Idiot Boy feeling?

My ambivalence has been greatly intensified by my recent involvement with Creativity Explored, a non-profit, combined gallery/studio space in San Francisco for artists with developmental disabilities of one sort or another – autism, mutism, schizophrenia and a number of other biogenetic frailties, often in combination with some form of impaired physical function. Admission to the programme is not open to anyone: the place is restricted to disabled adults with a demonstrable interest in art, and, though people come and go, enrolment remains at around 125 artists. The organisation was founded in 1983, and one of its goals was to provide a social community of sorts for its artists. As Lawrence Rinder puts it in the preface to Create, an essential part of the mission has been to ‘offer an experience that is … the antithesis of that envisioned by Roger Cardinal in 1972 when he coined the term “outsider art” to identify the work of artists who have no contact with the art world and who are physically and/or mentally isolated.’

Every month or so there is a show in the gallery at which work by the artists is for sale – with the profits going to the individual artists. The gallery is open to the public most days, and on weekdays, while the artists are there and working, one can see through a door of the main gallery into the huge adjoining studio at the back – a massive light-filled warehouse-space, the size of a basketball court – filled with adults of all sizes, ages and ethnicities. A deafening cacophony emanates from the studio: squeals, laughter, brash cries, along with an ongoing burble and roar of voices – a kindergarten on steroids. On weekends and during the Christmas show and other fundraising events, one can go into the studio and rifle through the great bins of recently created art or contemplate the vast piles of images spread out on work tables and thumb-tacked onto walls, all for sale. Prices for individual works depend mainly on size and materials, and range from $5 to around $150 or $200. All of the works for sale bear the artist’s signature, or else someone has written the artist’s name on the back for him or her. I have been known to emerge from such events carrying off armloads of stuff, like a looter after a hurricane.

I spell out the layout and economics of the place in part because much of my unease has to do with the experience, specifically, of becoming a ‘collector’ of outsider art. I first visited the studio during one of the holiday fairs – an experience I can only compare with Aladdin discovering his treasure-cave. As someone who struggles, often haplessly, despite having no traditional skills such as draughtsmanship, to create art of at least momentary value – usually collage, either the old-fashioned cut-paper kind or digital – I was staggered by the freedom, joy, profusion and utter fearlessness of the works I saw. The gigantic airy space was itself part of the effect. Awash in colour and excitement, it was like entering a liberating dream-world: buffeted by delight on every side, I stayed for hours and felt visually transported. I wanted to go home and drag out all my glue and paper scraps and start collaging (so to speak) like mad. Seldom have I felt so profoundly, if paradoxically, addressed by artwork; only the Goya ‘Black Paintings’ in the Prado, first encountered with a dreadful jet-lag hangover, have ‘spoken’ to me with such unexpected, tear-inducing, almost dizzying immediacy.

And yet to use words like ‘fearlessness’, or even ‘joyful’, is to assume a kind of normative psychology – if not an outright intentionality – that may not be part of the mental or emotive world of the artists themselves. In a terrific recent book, How to Look at Outsider Art, Lyle Rexer commented on the fact that many outsider artists, especially the most compulsive and mentally isolated, seem to feel little connection with the work they make after it is produced. There is no sense of possession, of that ‘look-what-I-made’ feeling – of adding to one’s personal storehouse of completed projects. The process of creation is the be-all and end-all; the product of little or no account.

One might attribute this lack of ‘authorial’ investment to the fact that, for whatever reason, many outsider artists have no deeply internalised sense of an audience – and some have none at all. Thus the work that looks ‘fearless’ to me may be nothing of the sort. It is not so much that the artist has triumphed over some inhibition or hesitation prompted by the thought that the work would later be judged. The work looks the way it does – that is, releases its astonishingly profligate energy and excitement – precisely because the artist, arguably, does not recognise or understand the idea of ‘being judged’, or indeed the concept of judgment itself. There is simply no one there to fear. Just as there is no one there to approve. For many outsider artists – the catatonic Martín Ramírez would be a compelling case – the making of the artwork would seem to be utterly unmediated by social relationships or the neuroses that result from them.

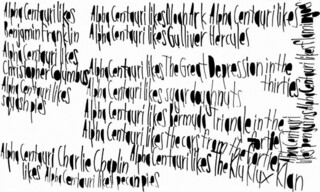

Which is another way of saying the archetypal outsider work is not a statement addressed to a viewer. It is not ‘rhetorical’, nor meant as communication. It is not produced to impress or charm or teach or convince. Paradoxically enough, this incommunicativeness can register as such with the viewer, even when the artist uses language as a primary part of his or her creative process. One of the Creativity Explored artists I collect is John Patrick Mckenzie, whose images are from one angle repetitive in the extreme. Mckenzie takes any surface he can – often white foam core – and prints streams of words across it using a black Sharpie pen. He has his own idiosyncratic, instantly recognisable style of letter-making: as he prints, he painstakingly fills in the negative space in any letter form that has a closed counter – ‘a’ or ‘b’ or ‘e’ or ‘g’. Thus:

It’s true that these wayward inscriptions sometimes hint at message-making – or at least at list-making. I own a mirror on which Mckenzie has written phrases and placenames that seem to refer, opaquely, to global warming. But overall, the repetitions work against a literal-minded transmission of meaning. At times Mckenzie’s visual mantras defy comprehension. This is not Gertrude Stein coyly subverting conventional English syntax or ‘making it strange’ on purpose; it is Mckenzie – mute, obsessive-compulsive and mostly unapproachable – soothing his odd automaton-soul through some primitive synchronisation of the motor control part of the brain with the still functioning (yet obviously anomalous) part devoted to language.

This apparent lack of rhetorical intent – the premium instead falling on compulsive productivity, as if one had to keep drawing or writing or splashing paint around, in the moment, or else one would fall off some psychic ledge – means that the works of the individual outsider artist do not usually show any artistic development over time, or exhibit any recognition on the part of the artist that some of his or her creations might be ‘better’ than others. One of the pleasures I have taken in outsider art, in fact, has been developing my own sorting process – an impromptu rogue connoisseurship, honed by my interest in contemporary art, by which I separate the things I find good from the things I think are bad. (It is surprising, still, how much we automatically associate aesthetic power and beauty with marketing and how much something costs.) In the case of the individual outsider artist one is typically confronted with a pile of similar works – all marked at around the same relatively low price, say, $10 or $20 – and it is up to the collector with his or her magical trolling eye to extract the potential jewels from the dross.

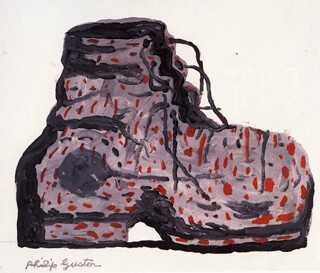

Some of my own greatest collecting moments occur when I uncover what I call an ‘accidental’ masterpiece – an outsider work, which, in a way obviously unintended by the artist, reminds me of the work of some much sought after and highly prized contemporary or major modern artist. Thus I have become adept (in my own mind at least) at landing on accidental Rauschenbergs, accidental Twomblys, accidental Jackson Pollocks, accidental works by Eva Hesse or Louise Bourgeois or Richard Tuttle or Jean-Michel Basquiat. (See recent coup to the right: an accidental Philip Guston. Guston’s 1968 painting Boot is above, and below a CE artist’s picture, now in my collection, of an eight-fingered glove.) At such moments, you not only feel that you have got something extraordinary for a pleasingly modest sum, but also that you have somehow exposed or demystified the artificially inflated prices of the ‘official’ art world – the whole pretentious and absurdly bloated economy of top-tier dealers, curators, biennials, and celebrity artists and collectors. How valuable can a flimsy Richard Tuttle wall-piece be, if the outsider artist James Castle (no relation that I know of) accidently managed to do something very similar using cast-off bits of cardboard and string in a trailer in Idaho? And yes, I enjoy a perverse feeling of triumph when art-savvy friends say of some piece, ‘Oh, whose work is that?’ expecting me to name at least some minor or local or possibly emerging art-world figure. It always seems to me that I am getting away with something: that the piece I’ve cannily if not slyly chosen is in fact a steal.

As well it may be. For at the very same time the outsider artist’s lack of possessiveness, his or her seeming lack of interest in the economic fate of any given piece, imparts its own ethical dilemmas. Even if one has paid for a piece, as I myself have discovered in moments of self-critical chagrin, one is likely to feel less of an obligation to credit its creator. I am embarrassed to admit – I feel slightly guilty in fact – that in some of the digital collages I have made I’ve sometimes incorporated bits and pieces from some of the outsider works that I own to serve as ‘background’ or as a Photoshop layer, say, to be blended with others. Am I engaging in artistic larceny by such appropriation – any more than I would be were I using, for example, a clipping from a magazine advertisement or sales brochure or newspaper? I recently published a book with one of my collages on the cover. The publisher – sensibly wary, for suddenly one was in a realm of copyrights and contracts and potentially out-of-control litigiousness – required that I obtain permission for every element making up the image, including the original photograph of blue floral wallpaper I used for a tiny part of the background.

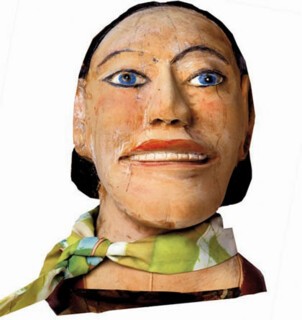

But then I have to ask myself, why do I feel somehow exempt from such due diligence when it comes to ‘borrowing’ elements from the outsider art I collect? I confess I’m cagey about it: I tend to use only small abstract swatches, and not blatantly representational or figurative elements. Rarely, I do borrow a face or figure – here’s one I’ve used several times, a magnificent woman’s face, carved and painted by the outsider artist S.L. Jones:

But I would be loath to put an image forward as one of ‘mine’ in which the head was the main element and went unchanged. And yet when I feel I have disguised the head enough – made it so only I could possibly pick out the obscure element I began with – – then that somehow makes the appropriation all right. I start to think I can get away with it and maybe I can.

Perhaps my moral quandaries will become moot soon enough. For the popular and critical recognition accruing to the outsider phenomenon over the past decade has meant that just like any other new, attractive and intriguing cultural product, outsider art is becoming more and more commercialised – and not just thanks to suddenly rapacious dealers. It seems inevitable that the outsider art market will at some point reach a kind of economic parity – and indeed become increasingly enmeshed – with the ‘real’ art market. A large and intricate Rizzoli drawing can now cost as much as $200,000; and Darger’s works have long been far beyond the reach of the ordinary collector. To get your very own Vivian Girl you must now compete with trendy museum directors and the edgier sort of hedge-fund manager or Silicon Valley CEO.

Though non-profit, Creativity Explored has itself begun licensing work by its artists to big companies, so as to increase sales and, one imagines, to create a larger audience for outsider art. Its most recent foray is an arrangement with the socially conscious urban design retailer CB2, an affiliate of the multimillion-dollar houseware company Crate&Barrel. CB2 is now offering its customers pillows, rugs and other decorative items imprinted with designs by Creativity Explored artists. I suppose this is a good development, though I can’t help wondering how much such marketing benefits the individual artists, and indeed if other parties do not now have a possibly dubious stake in these money-making ventures. The CE website is upbeat but vague on the subject of income derived from business tie-ins: ‘All CB2 products include CE artists’ signatures and are accompanied by a hang tag with a brief bio of the artist and a description of Creativity Explored. And best of all, a percentage of the sale of each of these products will go directly to Creativity Explored!’ Unaddressed here is the possibility that in this newly commercialised environment CE artists and/or their families or guardians might be vulnerable to exploitation by marketing agents or unseen corporate handlers. Though perhaps I romanticise the situation in a way that is condescending to the artists and unfair to the Creativity Explored administration, I can’t help but feel that a certain innocence has been lost. Even if the outsider artist won’t or can’t attach any commodity value to his or her work, it seems that more and more people are willing to do just that on his or her behalf.

The situation is such that you now encounter artists who have begun to market themselves, brazenly enough, as outsider artists. (Raw Vision has featured several of these individuals and their works.) But can you really be an outsider artist if you know what an ‘outsider artist’ is and that there is potentially money to be made from it? It annoys me no end to think of artists who may simply be capitalising on the sudden chic of the outsider phenomenon. And a lot of the work – precisely because of the calculation that may be involved – seems bogus to me.

What to make of it all? There is a short and wonderful poem, called ‘Outsider Art’ in The Best of It, a recent collection by Kay Ryan, in which she speaks of claptrap homemade objects ‘too dreary or too cherry red’.

If it’s a chair, it’s

covered with things

the Saviour said

or should have said –

dense admonishments

in nail polish

too small to be read.

No surface, she observes, ever seems equal to the psychic needs of those who create such crude and disquieting things:

Their purpose wraps

around the back of things

and under arms;

they gouge and hatch

and glue on charms

till likeable materials –

apple crates and canning funnels –

lose their rural ease. We are not

pleased the way we thought

we would be pleased.

Ryan lands here on several things that strike a chord. I find I share her dislike of outsider art in which a religious theme is central. There is a lot of it out there, especially in the South and the Bible Belt, and I usually find it repulsive: works like Howard Finster’s or Sister Gertrude Morgan’s apocalyptic visions of Jesus and the Angels, inevitably decorated with fanatical scrawlings from Scripture, the whole grisly, sado-masochistic baptised-in-the-Blood-of-the-Lamb thing. (Paradoxical, I know, somehow I don’t mind the frightful stuff in the Darger oeuvre.) I’m sure this dislike derives from the fact that I’m not by nature a religious person – indeed, at this late stage, have become a sort of blaspheming anti-clericalist. Diderot rocks. If my own Whiggish definition of outsider art goes something like this – art made by strangers of some absolute kind, persons permanently estranged from me, who live in a different world from the one I live in – then ‘religious’ outsiders are to me simply strangers to the nth degree.

At the same time, I have to confess that, like Ryan, a certain subtle displeasure is always present – lurking, you might say – in my response to outsider art. To all of it, that is – not just the work produced by those I think of as religious nutters. Even when I hear myself saying, Oh, I’m so fascinated by this picture; I love this artist; isn’t so and so amazing, I detect, invariably, some element of bad faith in my assertion. Because even when I like it, there is something in it that I very much don’t like, too. But what?

What draws me in with outsider art, I’ve concluded recently, is the promise – the colourful, bobbing lure – of meaning itself. I’ve been a lifelong sucker for meaning, one might say – if not an outright meaning-junkie. My greatest desire has always been for all the other human beings – you, for instance – to communicate with me, to tell me what you mean. If the meaning you’ve imparted is incomplete, convoluted, paradoxical, unresolved, I become upset and frustrated and want it all the more. Hence a lifetime spent as a university literature professor – as a sort of permanently genteel, middle-management meaning-broker. Milton: 10 per cent down, plus my 6 per cent commission. I began doing it because the greatest novels and poems always seemed to me like riddles demanding a solution. ‘The Faerie Queene’? Yes, it’s bloody, but we need to get to the bottom of it. ‘Middlemarch’? Well, let’s see … I have a hard time with incoherence and cognitive dissonance; such things make me anxious.

Yet precisely what draws me in – the meaning-bait – is precisely what shuts me out. After a certain amount of contemplation, my interest in any given outsider work can often go dead. I find, to my chagrin, that I have simply given up trying to understand or respond to it. It is a disturbing fact that as with children’s art, a great deal of outsider art doesn’t wear well. One tires of it – a certain depth-effect comes to seem lacking. One’s theories can never be tested. After a while the piece starts to look a bit dull and flat and you find yourself turning to Titian or Corot or Andy Warhol or (gulp) Tracey Emin with a certain relief. At this forlorn stage, you may even develop a distinct aversion to the once loved outsider piece: you’ve spent all that money framing it, you’ve made a place for it on the wall and in your life, but it’s suddenly become a meaning-suck, an object of hermeneutic displeasure.

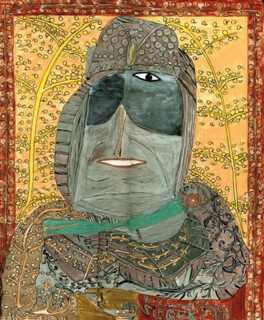

I cherish the work of one Creativity Explored artist in particular – his name is Peter. I love his art – or at least do for now. He is one of the more ‘presentable’ of the Creativity Explored artists – by which I mean that in person he is only slightly uncanny. Though he doesn’t exactly converse with anyone, he is often brought out at ‘meet the artist’ fundraising events held by the organisation. He seldom smiles and mostly hovers. Apparently he has a part-time job as a bagger at a Safeway store. Like that of most of the CE artists, Peter’s artwork is repetitive in style, but within the spectrum, has more variety, subject-wise, than most. He does portraits of local celebrities and politicians and desert panoramas featuring tumbleweed, cacti, coyotes, rabbits, Native American chieftains and women with papooses.

Not long ago I bought an astonishing picture Peter had made, oddly enough, of the helmeted Wotan, one-eyed father of the gods in the Ring cycle. It was a serendipitous and euphoric purchase – one of those amazing and exciting I-can’t-believe-this-is-only-$25 windfalls. The surprising subject matter made it all the more covetable.

But studying it more closely at home, I had to wonder: was the person I’d thought was Wotan actually Siegfried? Peter had given his subject the eye-patch traditionally sported by Wotan, but there at the bottom of the image, amid some passages of exorbitant, Klimt-like vegetal detail, was the serpentine little caption ‘Richard Wagner Siegfried’. A weird Jugendstil mystery, for sure. Did Peter know the story of the Ring? Had he seen or heard the opera? Or just seen the billboards advertising the San Francisco Opera version coming this summer? I’ve tried to address him now and then on the topic. But in my presence he remains sadly mute – on this and all other matters – and, indeed, I am not pleased the way I thought I would be pleased.

Some recent books on Outsider Art:

Create by Lawrence Rinder with Matthew Riggs and Kevin Killian (California, 179 pp., £16.98, July, 978 0 97193979 0)

Martín Ramírez by Brooke Davis Anderson (Marquand and the American Folk Art Museum, 2007)

Martín Ramírez: The Last Works by Brooke Davis Anderson (Pomegranate, 2008)

Henry Darger edited by Klaus Biesenbach (Prestel, 2009)

Everyday Genius: Self-Taught Art and the Culture of Authenticity by Gary Alan Fine (Chicago, 2006)

James F. Miles is a Boyfriend and a Girlfriend by Harrell Fletcher (Gallery 16 Books, 2007)

James Castle: A Retrospective by Ann Percy (Yale, 2008)

How to Look at Outsider Art by Lyle Rexer (Abrams, 2005)

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.