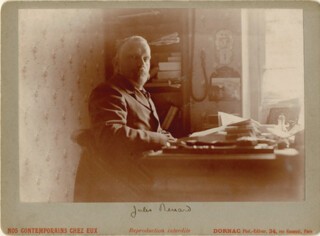

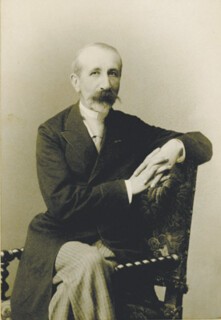

I own two photographs of Jules Renard (1864-1910). There is no indication of when either of them was taken, and at times I have wondered if they are really of the same man. In the first, from a series called ‘Nos contemporains chez eux’, he sits at a cluttered desk; behind him is a scruffy bookcase and a calendar showing the first of some month; on the floral wallpaper hangs a looped speaking tube, perhaps for ordering his mid-morning coffee. He looks wary and fierce, badger-like, as if he has just been dragged from his sett, stuffed into a suit that scarcely fits and ordered to face the camera: the result is one of the most ill-at-ease author photos I have ever seen. The second shows a leaner, older figure, perhaps thinned by final illness, identifiably the same person from the hairline, big right ear and droop of the moustache; otherwise he seems a different man, a different writer. Fingers elegantly interlaced, he poses in a tapestried chair of the studio photographer Pierre Petit (of place Cadet, Paris); he is in morning dress, with a huge knot to his tie and the visible ribbon of the Légion d’honneur (which dates the portrait to post-1900). He looks worldly, a confident man of achievement: perhaps a city mayor whose recent improvements to sewerage and street lighting have been much applauded by the bourgeoisie.

In fact, Renard was a mayor as well as a writer, though only of the tiny village of Chitry-les-Mines in the Nièvre, a remote part of northern Burgundy. Today, his statue stands a few metres from the mairie occupied before him by his father, a peasant turned builder, who was locally famous as the first suicide and the first public non-believer to be buried in the local cemetery. His son Jules, elected mayor in 1904, enjoyed his civic duties, handing out school prizes and marrying the locals. He also noted in his Journal the bifurcated feelings that came with being a writer-administrator: ‘As a mayor, I am responsible for the upkeep of rural roads. As a poet, I would prefer them to be neglected.’ However, there had been a much greater bifurcation to resolve earlier in his life: that between the Nièvre and Paris. Renard had the soul of a countryman, the ambition of a metropolitan, and the neediness of almost every writer. Talent, hard work and his wife’s dowry helped unify him as an individual, while her money allowed him to become the largest shareholder in the cultural monthly Mercure de France when it was founded in 1889.

His most famous work remains Poil de carotte (1894), the recognisably autobiographical tale of a red-headed boy growing up in a village much like his own. Its continuing power comes from its rejection of fiction’s sentimental myths about childhood: Renard wrote elsewhere that a child is a ‘small, necessary animal, less human than a cat’. Poil de carotte was much disliked in Chitry, not least for its harsh portrayal of the author’s mother. Even Renard’s father, to whom he felt closer, employed that parental withholdingness which infuriates writers even as they understand it: François Renard would notice copies of the books on his son’s desk but never ask to borrow one. Poil de carotte did not at first bring Renard the success he craved. This came only when he reworked the novel as a play, in 1900; for the Parisian stage then, read Hollywood now. Fame arrived, and the bridge between the two parts of Renard’s life was finally complete. You could say that in those two photographs, the first shows the countryman novelist, the second the citified playwright.

In Paris, Renard was thought an awkward customer – one sophisticate called him a ‘rustic cryptogram’ – who was liable to unsheathe his badger claws at any moment. In the Journal he diligently records criticisms made of him and his work. When his collection of nature notes, Histoires naturelles, came out in 1896, the novelist and critic Lucien Muhlfeld said to him: ‘There’s a lot of the priest in you, Renard. You keep remembering your first communion. You are on the side of morality, chastity and duty.’ Renard replied: ‘That’s right. I’m fed up with our literature consisting of stories about cuckolds.’ Despite this reputation as a disapprover, the Parisian Renard had a wide sweep of artistic and political friendships, from Rodin and Sarah Bernhardt to Gide and Valéry to Jean Jaurès and Léon Blum. His politics were socialist and Dreyfusard; he also moved in the circle around the Revue blanche. The first three editions of Histoires naturelles were illustrated by Félix Vallotton, Toulouse-Lautrec and Bonnard; Vallotton also decorated both Poil de carotte and La Maîtresse. By 1905, two texts from Histoires naturelles were already in use for dictations in the French School Cert. In 1907, Ravel set five of the pieces for voice. The Journal records a tricky exchange between writer and composer, with Ravel insisting that Renard attend the premiere and the writer remaining unconvinced that anything could be added to his texts by musical interpretation. In the end, Renard stayed at home, sending his wife and daughter in his place. This ambivalent attitude to the fame he sought is characteristic. Thus, his diary for 1896 is full of entries about Bernhardt, whose genius he reveres and whose person he puppyishly adores. Her acting strikes him ‘like a bolt of lightning’ which jerks him up in his seat. He records her asking if he wants to kiss her and then: ‘She kisses me, simply, on both cheeks. I kiss her just a little on the corner of the mouth, not daring to press.’ So far, so Frenchly predictable. But his diary entry for 16 December 1896 is absolutely typical of Renard: ‘If Sarah Bernhardt lifted her little finger, I would follow her to the ends of the earth – but with my wife.’

The Journal is Renard’s masterpiece, and it’s a long disappointment that it has never been published in Britain.* Apart from Poil de carotte and a much truncated Histoires naturelles in 1948, his only work to be translated here is L’Ecornifleur (‘The Sponger’) – which in 1952 was voted one of the 12 best French novels of the 19th century. Allusively autobiographical even to its title (in La Fontaine, the fox – le renard – is described as l’écornifleur), the novel concerns the early literary and emotional life of an ambitious but dislikeable provincial poet. Henri is trying to make it: professionally in Paris, sexually during a stay in the fictional Normandy resort of Talléhou (given the erotic chase that ensues, the name is presumably derived from ‘tally-ho!’). It is a witty study of hypocritical self-interest and genuine self-doubt – the young poet dislikes his first encounter with the sea because of the banality of his response to it, and the ‘trashy comparisons’ it provokes – which gradually turns bleaker, culminating in a still shocking scene of half-rape (‘le demi-viol’) that Renard’s publisher tried to cut. The connection with Vallotton (who was later to turn novelist himself) is indicative. L’Ecornifleur came out in 1892, and La Maîtresse, which Vallotton illustrated far more fully, in 1896. The latter is a caustic portrayal of the practical and emotional bargaining that precedes and oppresses an affair. This is exactly the world of Vallotton’s series of small, bold paintings called Intimités (1897-98) – emotionally ambiguous, suggestively harsh explorations of the faultlines of the bourgeois sex relationship.

Renard moved easily between fiction, journalism and drama; subject matter, tone and even characters overlap. He also imported into his novels the playscript’s blunt way of setting out dialogue (thus avoiding fiction’s repetitive he-said-she-said, followed by that over-familiar adverb to illustrate tone). The novelist was rightly proud of this innovation, until – and it is the fate of most writers who imagine they have invented some new formal device – he discovered it in the earlier writings of the Comtesse de Ségur. As well as being a happy overlapper, Renard was also a cheerful recycler: the Histoires naturelles went through many editions, and the author would frequently import new material from his voluminous occasional writings. (It’s also been pointed out, rightly, that if you trawled the Journal you could put together a second and third collection of nature notes, of just as high a quality.) Douglas Parmée nicely continues this tradition of intra-larceny, adding, for example, ‘Le Lever du soleil’ from the collection L’Oeil clair. His elegant and humorous translation is accompanied by Bonnard’s sunny black and white sketchings.

A year before publishing Histoires naturelles in book form, Renard compared his approach to that of Buffon, the 18th-century naturalist (and grand seigneur to Renard’s country lad). ‘Buffon described animals in such a way as to please humans. Whereas I want to please the animals themselves. I would like my book, if they could read it, to make them smile.’ This makes Nature Stories sound cuter than it is. There is not a streak of sentimentality in Renard, and the world of Jemima Puddle-Duck is far away; bunnies here are flopsy only when in the mouth of a gun-dog. Animals are given their full reality and dignity, strangeness and purpose. Buffon and other traditionalists also liked to impose on the natural world a hierarchy reflecting that of human society: thus the horse is nobler than the donkey, the swan posher than the goose. Renard, by contrast, is a socialist among the animals. He looks at disregarded or unattractive beasts with understanding: he rehabilitates the bat, and thinks the pig’s squalor our fault rather than his – ‘If they cleaned you up, you’d look fine. If you neglect yourself, it’s their fault.’

But however instinctively democratic the approach, there remain beasts that are inescapably boring, or repetitive, or irritating. The gudgeon, for instance, is so stupid that it first swims into an unbaited bottle, then into Renard’s net, then throws itself on his baited hook, as if in some tedious suicidal drive. Then there is the pet canary, annoyingly unable to appreciate the advantages to caged life, and even lacking in basic bird skills:

I tie a biscuit onto a string between two bars of his cage and he eats the string … He washes himself in his drinking water and drinks his bathwater … he hasn’t yet realised what salad leaves are for; he just tears them into shreds. It’s pitiful to watch him when he really wants to peck up a seed. He rolls it to and fro with his beak, squeezing it, crushing it and twisting his head about like a little old man who’s lost all his teeth.

Renard soon gets fed up with ‘this dumb bird’ and sets it free through the window, trusting that it won’t be found and brought back to him: ‘Not only am I not offering any reward but I’ll swear that I have never known that bird.’

But caged animals are somehow not quite authentic; nor are exotic zoo animals (which are allotted a brief page). Just as Renard rarely went abroad, and didn’t think much of foreign literature, he was a patriot – or isolationist – in animal matters as well. The farmyard beasts, hunted game, insects and birds of the Nièvre were world enough for him. Sometimes their activities add up to a story, sometimes an extended observation; or they might just provide a joyful moment – for instance, when a kingfisher comes and perches on his fishing-rod (‘I was swelling with pride at having been taken for a tree’). And on almost every page there are brilliant descriptions and comparisons. A peacock ‘lifts the tail of his gown, which is weighed down by the gaze of those who’ve been unable to take their eyes off him’. A butterfly is ‘a love letter, folded in two … looking for a flowery address’. The section on frogs is virtuosic, reminiscent of Martian poetry. First Renard hands out a series of fine similes:

They’re leaping out of the grass like heavy drops of frying oil.

They pose, like bronze paperweights, on large water lilies.

One of them is soaking in air. Through his mouth, you could drop a coin into the money box of his stomach.

Then his comparisons become stranger, more elusively allusive:

Squatting like tailors, they’re yawning, stupefied at the setting sun.

Then, like street vendors deafening people as they yell, they croak the latest news items of the day.

They’re giving a party this evening, at home. Can’t you hear them polishing the glasses?

It isn’t just the animals who attract Renard’s skill at description and comparison. A close-growing group of trees ‘gently stroke one another’s branches, to make certain they’re still there, like blind people’. In autumn, ‘the poplar that is standing upside down in the canal will be attracting the leaves of the poplar standing on the bank, right way up.’ And here is the effect of that season’s first cold snap:

There’s been a white frost; the dahlia leaves are as crumpled as after a ball. The tomatoes are bursting open and juice is oozing out of their frostbites; the haulms of the potatoes look as if they’ve been cooked; but the sorrel has been nicely ironed and is resisting, as is the delicate frizzy beard of the carrots and long, soft ears of the beetroot.

But the natural world is also one of constant danger and death, with the greatest predator being man himself. I remember a French peasant-priest telling me, many years ago: ‘It’s strange, Monsieur Barnes, I love animals, but I kill them.’ He said it as if it were a paradox only God could resolve. Renard, though pretty much agnostic (‘I don’t know if God exists, but it would be better for His reputation if He didn’t’), was similarly poised between entranced admiration for the birds and beasts, and a tender-hearted, sometimes guilty hunting of them. Hare and partridge fell regularly to his gun. Another bifurcation. Even normal human interaction with the animal world can be surprisingly brutal. A vet bleeds a cow: as the mallet strikes the lancet home, a lavish spurt of blood fills the pail usually awash with milk. A peasant beats a dog almost to death when he finds it copulating with his own dog. Renard himself kills his daughter’s pet dog once it has become incontinent and smelly:

It was quite simple: you insert two powders, potassium cyanide and tartaric acid, into a cut you’ve made in a piece of meat and you carefully stitch it up with a very fine thread. First you give a little ball of meat which is harmless and then the important one. As the stomach digests this, a chemical reaction turns the two powders into hydrocyanic or prussic acid and that’s that.

However, even as committed a countryman as Renard can tire of slaughter. He brought his own shooting season to a close on 1 September 1904. In his Journal, immediately below another typical animal entry (‘Pig: a potato with ears’), he explained his reasons. He had seen a lark fly up, then perch on a clod of earth. ‘It’s dangerous to have a gun. You think it doesn’t kill. So I shoot, not because I want to kill the bird, but just to see what would happen.’ Inevitably, he doesn’t miss, and then describes the bird on the ground leaking blood, feet waving, beak opening and closing. ‘I tore up my hunting licence and hung up my shotgun on a nail in the wall.’ Another bifurcation in his life was finally resolved.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.