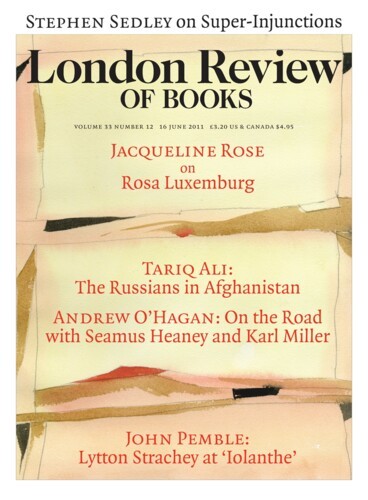

Something remarkable happened one night in 1920, during a performance of Iolanthe at the Prince’s Theatre. After the chorus had sung

To say she is his mother is an utter bit of folly!

Oh, fie! Our Strephon is a rogue!

Perhaps his brain is addled, and it’s very melancholy!

Taradiddle, taradiddle, tol lol lay!

the man sitting next to Maurice Baring turned to him and said: ‘That’s what I call poetry!’ He then predicted that the operas of Gilbert and Sullivan would be the most enduring achievement of the Victorian age. The incident is remarkable because the man was Lytton Strachey and he wasn’t joking. No Bloomsbury raspberry here. The famous debunker of eminent Victorians was handing out a bouquet to the most eminently Victorian of them all. He’d been hooked ever since he’d first seen Iolanthe in 1907. ‘It’s impossible to believe that a lord chancellor in love with a fairy can be anything but ridiculous,’ he told Leonard Woolf; ‘but one goes, and when the moment comes, it’s simply great … I should like to go every night, for the comedy and wit is as enthralling as the tragedy.’

Strachey wasn’t far wrong, either. What even Victorians regarded as Victoriana at its most ephemeral has outlived the Crystal Palace, the British Empire and Punch. No sooner is it diagnosed as terminal than it rallies and thrives. For half a century after Gilbert’s death in 1911, the operas were kept in the professional repertoire by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, which owned the copyrights, and in the amateur repertoire chiefly by boys’ schools and universities, where they were favoured as a surrogate sport for the unathletic. D’Oyly Carte functioned at the margins of the cultural establishment as unofficial trustee of part of the national heritage, cherishing Gilbert and Sullivan like a precious heirloom. Everybody might look, but no one must touch. Performances were always and everywhere as predictable as church services. D’Oyly Carte replicated the original productions, and the amateurs were required to replicate D’Oyly Carte. Scenery, costumes and stage business were all strictly regulated, changes to words or music forbidden. The copyrights were due to expire in 1961, and a campaign was fought to extend them. The campaign failed, and the highbrows rubbed their hands and moved in for the kill as their old middlebrow bête noire found itself middle-aged and broke. Harold Wilson and Spike Milligan joined forces to save it, but the D’Oyly Carte Company sank in 1982, scuppered by the Arts Council. The hope and expectation clearly was that the whole show would vanish with it. HMS Pinafore would go down with the last of the Savoyards on deck, singing ‘For he is an Englishman!’

Thirty years on, HMS Pinafore is still afloat. Refitted and relaunched by directors like Joseph Papp, Jonathan Miller, Ken Russell and Mark Savage as post-copyright, post-D’Oyly Carte G&S, not only Pinafore, but The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado and Princess Ida too have been successfully revived on both sides of the Atlantic. Showbusiness professionals now admire Savoy opera as a prototype of the Broadway musical; and Topsy-Turvy, Mike Leigh’s subtle and selective take on the collaboration/conflict between Gilbert and Sullivan, made a box-office hit out of a period soap opera. Still in the repertoire, G&S is now in the academic canon too, and there’s a lot less talk about culture for the culturally retarded or opera for the musically illiterate.

What, then, is it? A hybrid, it seems, strung between two worlds: one right side up, the other upside down; one historical, the other not. It’s the language of Mendelssohn, Bizet, Gounod and Offenbach: as Victorian as pressed flowers and ottomans. It’s the sound world of the British upper crust and bourgeoisie at their most genteel, sentimental and dressy. Nothing more exasperated George Bernard Shaw than Sullivan’s habit of conducting in gloves, and nothing more exasperated Sullivan than Gilbert’s inverted universe of puppets and paradox. Regiments led from behind, sons older than their mothers, dysfunctional utopias, flying peers and elliptical billiard balls belong with a paraphernalia of satire and absurdity as timeless as Aristophanes. Beyond that, Savoy opera complicates definition and eludes judgment because it’s always on the point of turning into something else. The music works to humanise and historicise the text; the text works to dehumanise and dehistoricise the music – so it’s fully neither yet simultaneously both of its antithetical worlds. It made both Sullivan and Gilbert rich and famous but satisfied neither, because each believed he was effacing himself for the glory of the other.

The double world of these operas has always generated a divided critical response. The Victorians were happy with Gilbert and unhappy with Sullivan. To them, Gilbert’s lampoons never seemed more than innocuous teasing. After some initial fuss (Trial by Jury was trounced because it sent up the judiciary; The Sorcerer because it featured comic clerics), the satire ceased to offend – which meant, as the Victorian critic William Archer pointed out, that it ceased to be satire. In fact, it was a sort of apotheosis. Gilbert’s caricatures made W.H. Smith, Sir Garnet Wolseley and Oscar Wilde popular celebrities. Wolseley was so tickled by being portrayed as Major-General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance that he learned the show-stopping ‘Modern Major-General’ patter-song and performed it at parties. Gilbert communicated no real sense of chaos or panic because the instability of the world his characters inhabit is corrected by the stability of the language they speak. Lunatic logic and accelerating disorder are checked by metrical and elocutionary discipline. Victorian audiences were especially alert to this discipline, and imitated it, because they followed performances with copies of the libretto, all turning their pages at the same time. On the other hand, they were much less alert to the violence and cruelty in Gilbert’s humour. Jokes about decapitation, boiling oil, torture, burial alive and solitary confinement had them rolling in the aisles. ‘There is nothing remarkable about this happy jingle,’ Maurice Baring said of the trio in Act I of The Mikado:

To sit in solemn silence in a dull, dark dock,

In a pestilential prison with a life-long lock,

Awaiting the sensation of a short, sharp shock

From a cheap and chippy chopper on a big, black block.

Sullivan, though, was a problem. Nurtured as the nation’s prodigy, he’d turned into its prodigal son. Stung by foreign jibes about ‘das Land ohne Musik’, the Victorians had invested heavily in concert halls, in the Covent Garden opera house and in Sullivan (humbly born but brilliant) as Britain’s budding great composer. But instead of attending to his destiny as Beethoven’s successor and Britain’s answer to Berlioz and Brahms, Sullivan became a domesticated Offenbach, squandering his gifts on trivia in order to finance a playboy lifestyle. ‘They trained him to make Europe yawn,’ Shaw said, ‘and he took advantage of their teaching to make London and New York laugh and whistle.’ Queen Victoria told Sullivan he should write a grand opera. Dismay intensified when he obeyed and made everyone yawn with Ivanhoe. Then Elgar arrived and Britain recognised what it had been waiting for. Sullivan’s shortcomings no longer mattered, and the nation ditched his serious music, retaining only ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ and ‘The Lost Chord’ for old times’ sake. Henceforth he would be taken – or left – as a minor though by no means negligible composer who found his true vocation in giving Gilbert’s marionettes brief but memorable moments of being.

After Sullivan had ceased to be a problem, Gilbert became one – precisely because he hadn’t been one for the Victorians. Savoy opera fell into disrepute in the 1960s and 1970s because under radical, postmodern and postcolonial scrutiny it began to look like a universal archetype of political incorrectness: homophobic, imperialistic, misogynistic. The gruesome comicality in The Mikado suggested either sadomasochism, or racism of the type that depicted Africans as cartoon cannibals. Rehabilitation was slow. In 1986 David Eden argued in a psychoanalytical study that the cruelty was sadomasochism of an infantile, and therefore less than sinister, kind. Gilbert, like his characters, inhabited a pre-genital universe somewhere between fairyland and nightmare. Accusations of homophobia seemed less plausible after Mark Savage’s outrageously gay Pinafore!, staged in Los Angeles in 2001 and in Chicago and New York in 2003.

But nagging doubts about Gilbert remained – especially among feminists, antagonised by his depiction of middle-aged women. A recurring figure in his libretti is the menopausal spinster with fading allure and a voracious libido. Recently, historicist criticism has been working at erasing this blot on Gilbert’s reputation too. His biographer Jane Stedman has pointed out that in creating these characters for female performers, Gilbert was both making them less grotesque and reclaiming for women the right to represent themselves – since in traditional comic theatre the Dame was a transvestite role. And now Carolyn Williams, a feminist critic, has published a searching analysis of the thinking behind Gilbert’s libretti, and delivered a verdict of ‘not guilty’ on the charge of misogyny. Her book is, in its way, as unexpected and remarkable as Strachey’s compliment of 1920.

In Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody, Williams agrees that music and text pull in different directions. Savoy opera is ‘parody interrupted by feeling’. Nevertheless, she requires us to rethink our assumptions about polarity, because she argues that Gilbert was as much a product of his time as Sullivan. His world, too, is historically specific. He worked within, and against, Victorian theatrical genres – which means that critics who read him ‘straight’ misread him. Only The Yeomen of the Guard, she insists, can be taken at face value. It’s a mistake to see Gilbert as a licensed jester making mischievous but harmless fun of the establishment he doesn’t want to disturb. This was true of Sullivan, who is irreverent but not iconoclastic. When Sullivan quotes or mimics Handel, Donizetti, Gounod, Verdi or Wagner, he’s merely using them for dramatic or comic effect; he’s not mocking them. But Gilbert does mock. There’s a corrosive bite to his libretti, which both satirise Victorian life-as-theatre and parody Victorian theatre-as-life.

‘Savoy opera,’ Williams writes, ‘does not offer the explicitness of radical theatre, but a more subtle indirection whose critical value should be taken seriously nevertheless.’ By the time of Utopia, Limited (1893), this critique has become ‘bitter’. Gilbert is now raising ‘profound and dangerous questions’; his script is striking for ‘the darkness of the political analysis’. To Gilbert, Victorian life and Victorian theatre were absurd and unjust because dehumanising. Their institutions, rituals and conventions reduced individuals to gender stereotypes and class caricatures: trammelled personality with the constraints of performance. Indignation drives both his satire (which indicts the law, Parliament, corporate capitalism and the empire), and his parody (which targets music hall, opéra bouffe, extravaganza and melodrama). It’s the parody that interests Williams most, and her book is essentially about Gilbert as a critic of Victorian theatre: theatre that transmogrifies foreigners; trades in ludicrous coincidences, revelations and transformations; portrays women as either nubile dolls or sexually frustrated pantomime dames. Far from being a misogynist, she argues, Gilbert was a proto-feminist. ‘We should not,’ she warns, ‘make the mistake of reading the Savoy Dames straight.’ With the exception of Lady Blanche in Princess Ida, ‘the large contralto characters’ are ‘not the misogynistic figure itself, but a parody of that figure’. Gilbert isn’t mocking plain, middle-aged women. He’s mocking people who mock such women, because such women are not to be mocked. ‘Of hasty tone/with dames unknown/I ought to be more chary,’ says a chastened Lord Chancellor in Iolanthe:

It seems that she’s a fairy

From Andersen’s librāry

And I took her for

The proprietor

Of a ladies’ semināry!

The Fairy Queen and other Gilbertian women of a certain age exhibit ‘thrilling, indeed massive, female power and a protest against namby-pamby femininity’ – like Disraeli’s ‘Fairy’, Queen Victoria herself.

Such indirection is indeed subtle – but, we are assured, only for us. We are prone to misunderstand Gilbert’s parody because we’ve lost sight of the theatrical genres he’s parodying. Victorian audiences were still familiar with them, and regarded them as old-fashioned and laughable. By holding up to them a distorting mirror, Gilbert enhanced their risibility and clinched their obsolescence. This is the least convincing claim in Williams’s argument. It seems inherently unlikely that Victorian audiences knew they were swallowing such subversive stuff. Parody is notoriously esoteric – even Shaw missed Gilbert’s – so we must surely assume that Victorians read Gilbert much as people nowadays read, say, The Name of the Rose: straight. Gilbert always felt he was misunderstood; that’s partly why he was so chronically belligerent.

The exoneration in Williams’s book isn’t complete. She’s disturbed by Princess Ida, that awkward and uncharacteristic product of the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership. It’s about an all-female university, but clearly isn’t parodying single-sex education. In fact, it’s not clear that it’s parodying anything. Gilbert described his libretto as a ‘respectful perversion’ of Tennyson’s poem The Princess, and Williams reckons that it’s too respectful by half. It imitates – but doesn’t parody – Tennyson’s decasyllabic blank verse; it exaggerates (again without parodying) Tennyson’s conventional gender stereotyping. The female students forsake their ivory tower because they realise that a woman’s true calling is to be not a bluestocking but a wife and mother. It’s mostly cheap burlesque and male chauvinism – yet Gilbert is forgiven, because women come out on top in Patience and Iolanthe. His inexcusable lapse is The Gondoliers, which is shamefully anti-republican. ‘Socially, logically and sociologically,’ Williams writes, ‘The Gondoliers presses towards the reductio ad absurdum of ideals of equality.’ She takes especial exception to the jolly lyric in Act II: ‘When everyone is somebodee/Then no one’s anybody!’

A satirical squib against the snobbery of rank? Not so. It’s ‘cynical and pseudo-logical … the culmination of the opera’s satire on republicanism’. Here Williams seems to be falling into the error she’s been warning against – missing the point by reading Gilbert straight. She leaves us wiser nonetheless, because she shows that misreading Gilbert depends on where, as well as when, you are born. It needed an American critic to tell us why The Gondoliers, despite its sunny music, has always left American audiences cold.

Instead of developing his art, Gilbert drove it until it collapsed. The Grand Duke (1896) was the last of the Savoy operas, because by now the parody had degenerated into puerility. Not even Sullivan could lift Gilbert’s characters into the world of adult feeling. People stopped laughing, and it’s all the more sad because no one has ever been able to take Gilbert seriously when he isn’t being funny. His serious work, which he regarded as his most important, failed to float, and it’s now at the bottom, together with Sullivan’s sunken cargo. The reason, as Williams has made clear, is that he was truly serious only when he was truly funny.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.