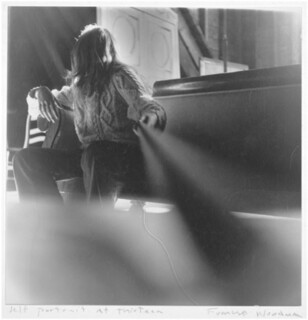

In 1972, at the age of 13, Francesca Woodman photographed herself sitting on the end of a sofa at her home in Boulder, Colorado. The room looks like a studio; Woodman’s parents were artists, and there’s a sliver of easel behind her. A grey blur seems to issue from her half-raised left hand and flood the bottom of the black and white picture like a fog. The blur has been generated partly by the out-of-focus cable release she used to take the photograph; the rest has been achieved in the darkroom. The photographer herself is in focus, but she’s buried inside a big cable-knit sweater and has turned her head away so that her darkish blonde hair is all we see. (There’s something monstrous and comic about this faceless head, like the hairball Cousin Itt from The Addams Family or the unkempt ghost in Hideo Nakata’s film Ringu.) Her right arm is a blaze of light on the arm of the sofa, so overexposed that the hand seems to hover unattached: the only expressive gesture in a picture that is all veils and avoidance.

So much of Woodman’s subsequent imagery and artifice is already present in Self-Portraitat 13 that it almost undoes any sense of her development as a photographer. There is the domestic yet mysterious setting, the Gothic ambitions, the use of blurs conjured by various technical means, the deployment, both open and furtive, of her own body. The atmosphere in her photographs is literary – tricked up out of Lewis Carroll, Poe and Surrealism – as well as knowingly indebted to photographers from Julia Margaret Cameron to Duane Michals. One of the effects of the current survey of her work at Victoria Miro (until 22 January) is that one keeps imagining there’s a photographic education going on, only to discover that some particularly sophisticated or unsettling image – the artist half-buried in lakeside mud or become a hazy whorl inside a mirror – was taken in the first three years of her career. Woodman seems to have arrived fully formed as an artist and done her enigmatic, theatrical and sometimes naive thing until she stopped.

That’s to say, for only nine years. She was given a camera by her father at 13 and three years later enrolled at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. She spent time in Florence and Rome, and in 1980 was an artist-in-residence at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. Much of her best work grew out of school projects and assignments. She published just one book, a week before she died. At the age of 22, after a period of depression, some apparent setbacks in her career and the end of a relationship, she threw herself from a window in New York. Her suicide is part of the Woodman mythology – it couldn’t be otherwise, given the fragility she exhibits and the morbidity she courts in the work – but it has not really determined her reputation. Instead of a doomed prodigy, she’s long been acknowledged as an artist with a keen sense of photographic history and a subtle take on certain vexing issues of her day: the relation of performance to its photographic record, the extent to which one could play critically with the clichés of femininity, the inherent falsity of photography itself.

It’s not hard to see why Woodman’s photographs have so excited academic critics. Her painterly and photographic references are daring and precise. She poses as a woman out of Vermeer at a table scattered with fruit. She flails before the camera until she’s an inhuman blur, invoking Francis Bacon, aiming, in her words, to make ‘something soft wriggle and snake around a hard architectural outline’. She crawls half-naked into cupboards in homage to the odd dandyish self-portraits of Claude Cahun. When she plays dead on the floor, crams herself into a museum vitrine or binds her legs in tight spirals of tape, you think of the photographs Hans Bellmer took of a fetish doll of his own devising in the 1930s. She explores a disused factory in Rome and a bare arm pokes through the wall, like the living candelabra in Cocteau’s La Belle et la bête.

Then there are the more or less elaborate frames and apertures – allegories of the square-format image she favoured – by which she effects her apparitions and disappearing acts. Here she is behind the shutters of a tall window, or apparently trying to climb into a large wood-framed mirror. She hovers or hangs in doorways, gets trapped in a rotting old fireplace, slips behind the wallpaper, vanishes from view as a dilapidated door unhinges itself and levitates in a bare room. The nod to spirit photography is more explicit in a series of pictures in which she is seated and dressed in black, her hands splayed before her and glowing, or in the photograph where she opens her mouth and a stream of transparent letters floats out like ectoplasm. At times she’s no more than a ghostly imprint on the floorboards, realised with a dusting of flour and some judicious heightening of contrast in the darkroom. She seems to have been precociously aware of photography – and especially self-portraiture – as a knowing game of hide and seek.

And yet for all their sophistication the strange appeal of these photographs also derives from Woodman’s youth, from the way she seems to know and not to know exactly what she is doing. It’s possible to read her willowy, blurred nudes among picturesque ruins as the product of an adolescent aesthetic: culturally hothoused and overinvested in Surrealist and Gothic precursors. There are hints that she was trapped not in these decaying rooms but inside her own self-fashioning – she once wrote to a classmate that she was as sick as anybody of looking at herself. Except that she also played with the iconography of the tragic teen aesthete: she knew that cliché and its lineage too well. What she does not seem to have known is just when her treatment of this style tipped over into kitsch. Some of her photographs are merely texturally lovely; she was clearly attached to traditional techniques of printing and retouching. Others, such as a late series of Man Ray-ish nudes, resemble too closely the fashion photography that is always stylistically in the wings when one looks at her work. She greatly admired the fashion photographer Deborah Turbeville, whose images of neurasthenic models in Mittel-European grey gardens and Bellmer-like interiors where young women play the inanimate love object now look, unfairly, like airbrushed versions of Woodman.

Given her immersion in the past and the claustrophobic world she depicted, it’s not clear what kind of artist Woodman might have become. Biographical reports suggest that when she moved to New York in her early twenties she became dispirited at the lack of ready acceptance of her work. She had begun experiments with video, and a few of the photographs at Victoria Miro point to a more expanded practice; her jagged handwriting adds captions as if from a diary to the images, treating them more as objects than as portals to her unconscious. Perhaps, fed up with me-decade self-advertisement, she might have disappeared altogether from her own photographs, as she threatens to do in a rare colour print from 1979 – shinning up a door frame and leaving an empty mirror behind her on the floor.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.