Sarah Bernhardt’s strangest gift – or so it seems a hundred years after the fact – was her ability to make the most improbable people go cuckoo over her. An otherwise mopey young D.H. Lawrence, for example. In 1908, having seen her perform one of her signature roles – Marguerite, the doomed courtesan in La Dame aux camélias – Lawrence sounds like a decadent schoolgirl on heat: ‘Oh, to see her, and to hear her, a wild creature, a gazelle with a beautiful panther’s fascination and fury, sobbing and sighing like a deer sobs, wounded to death, and all the time with the sheen of silk, the glitter of diamonds … She represents the primeval passions of woman, and she is fascinating to an extraordinary degree.’ If you say so, Lorenzo – she was 63 at the time.

Ordinarily cool and spinsterish, Willa Cather lights up like a Christmas tree in the Divine One’s presence: Bernhardt’s ‘bursts of passion blind one by their vividness … It is like lightning, gone before you see enough of it, and indescribable in its brilliancy.’ The actress’s art, she declares, is sheer voluptuous ‘dissipation’ – ‘a sort of Bacchic orgy’. When one of the more dour and sober-sided American writers of the past century starts burbling on about Bacchic orgies and ‘indescribable’ brilliance, you know the pink candyfloss has started sticking to your face.

But what – most peculiar of all – to make of Freud? As a young man studying the aetiology of hysteria with Charcot in Paris in 1885, he saw Bernhardt in Victorien Sardou’s Théodora and gushed about it to his long-suffering fiancée, Martha Bernays:

How that Sarah plays! After the first words of her lovely, vibrant voice I felt I had known her for years. Nothing she could have said would have surprised me; I believed at once everything she said … I have never seen a more comical figure than Sarah in the second act, where she appears in a simple dress, and yet one soon stops laughing, for every inch of that little figure lives and bewitches. Then her flattering and imploring and embracing; it is incredible what postures she can assume and how every limb and joint acts with her.

What sort of ‘incredible’ postures? Poor Martha must have wondered. Elsewhere the newest Bernhardt fan complains that he can’t concentrate: the actress has left him ‘reeling’.

The reader may be reeling too at this point – at the sheer freaky incongruity of it all. Sarah and Sigmund: the imp-brain runs amok. Odd counterfactuals begin to form in the cerebrum. What if the inventor of psychoanalysis had ‘seen’ Bernhardt: not just in the theatre, but as a patient? He could have written her up like Anna O or the Rat Man! ‘Female Narcissism: The Case of Sarah B’. ‘Curtain Calls and Their Relation to the Unconscious’. ‘Stage Make-Up and Its Discontents’. ‘Théodora: A Case of Byzantine Hysteria’. He might even have named some crucial analytic concept after her: the Female Ovation Complex, perhaps.

And indeed, why not? As Robert Gottlieb’s concise yet stylish new biography reminds us, the great actress’s sumptuously chequered life would have presented even the most dimwitted Viennese shrink with a veritable orchestra pit of things to quiz her about. Consider, Herr Doktor, some of the diagnostic highlights:

1. The Family Romance. Shady Prostitute-Mother and Unknown Father. Precocious Sexual Enlightenment. Bernhardt’s mother, an elegant and pragmatic Dutch courtesan called Youle van Hard, trained her daughter from infancy for the life of a grande horizontale. Which is to say, Youle pimped for little Sarah high and low, though mostly in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré. One of Youle’s well-connected gentlemen friends was responsible for the adolescent Bernhardt’s entry into the Conservatoire, the acting school run by the Comédie-Française, in 1860. Bernhardt’s father? Lost in the mists of etc. Youle was a single mother – and not an especially warm one either – but I guess you could say She Was Doing the Best She Could.

2. The First Rakish Lover-Patron. The dapper Prince Henri de Ligne, moustachioed Belgian man of the world and ‘fantastic swell’, who set Sarah on her way in the more Nana-like circles of Parisian high society. He seems to have picked her up in the Tuileries Gardens one day. Bernhardt always had at the ready a more romantic account of how they met – several of them in fact. She told her granddaughter late in life that she and Henri had met at a costume ball in Brussels. She had been dressed as Elizabeth I; he – appropriately enough for a prince – had been a slim, pomaded, unusually fetching Hamlet.

3. The Doted-On Wastrel Son. Prince Henri’s By-Blow, Most Likely. Bernhardt had him in 1864, when she was 20. She named him Maurice but she might as well have called him Oedipus: the actress would remain besotted with him for life. The prince, as putative father, was less enthused. When Bernhardt, improvident after her lying-in, asked him for money, he replied: ‘I know a woman named Bernhardt, but I do not know her child.’ Ferociously ambitious, or so the legend goes, Bernhardt thereafter determined to live by her wits and beauty and win financial independence – for her son’s sake – on her own rough and ready (or silky and satiny) terms. Maurice trailed around behind her for the rest of his life, wheedling money and gifts and expensive motor cars out of her.

4. The Early Narcissistic Wish-Fulfilment. Those First Astonishing Stage Triumphs. Bernhardt’s uncanny stage presence, thrilling voice and eerie beauty – her hair was naturally reddish and inclined to frizz up poetically under the lights – flabbergasted audiences everywhere. Though slight in build (almost anorexically thin at the start of her career) she combined a fine-edged classical technique with sultry, skronking, incendiary passion. A trill a minute, from one rockin’ tirade to the next: she left ’em limp and ravaged. Among the Bernhardt breakout roles: Doña Marie, the tragic Queen of Spain in Hugo’s Ruy Blas (1872); Racine’s Andromaque (1873) and Phèdre (1874); Doña Sol in Hugo’s Hernani (1877); Marguerite in La Dame aux camélias (1880); Adrienne Lecouvreur, in Scribe and Legouvé’s eponymous tear-jerker (also 1880); and Fédora, doomed title character in the first of several wildly popular melodramas – La Tosca and Théodora would follow – Sardou wrote for Bernhardt between 1882 and 1903. (Besides being the first of his ‘shabby little shockers’, as Sardou himself called them, Fédora also gave its name to the now once again ubiquitous hat: Bernhardt, playing an unfortunate Russian princess in love with a man whom she mistakenly believes is a nihilist, sported one, and it immediately became the craze – first for women, somewhat later for men. Gender outlaws, take note: tough-guy-hipster-fedora-favourers – Al Capone, Humphrey Bogart, J. Edgar Hoover, William S. Burroughs, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Depp – might all be considered unwitting imitators of Sarah Bernhardt.)

5. The Rampant (er … ) Erotomania. (One moment, Herr Doktor – cough cough – my throat is tickling me.) World famous by her late twenties, Bernhardt slept with virtually every other famous person she encountered. Sexual partners included most of her leading men, notably sexy beast Jean Mounet-Sully, her beefcake colleague at the Comédie-Française in the 1870s (later known for his priceless mot, ‘until I was 60 I thought it was a bone’); the geriatric but still game Victor Hugo (he had directed her in her first Ruy Blas); Hugo’s political arch-nemesis, Louis-Napoléon (politics aside, Bernhardt always had a soft spot, she said, for the entire Bonaparte family); Charles Haas (elegant model for Proust’s Swann); ‘Bertie’, the cuddly future Edward VII; the artist-engraver Gustave Doré; and at least one woman, the trouser-wearing sculptor Louise Abbéma. Gottlieb refers to Abbéma, somewhat ungallantly, as ‘mannish’ and ‘monkeylike’, and it’s true, the pint-sized Louise wasn’t exactly an oil painting. Having Susan Boyle eyebrows didn’t help. But she and Bernhardt – who studied sculpture with her (and achieved something rather more than mere amateur competence) – unquestionably had an amitié douce for life. Sometime in the late 1870s they posed for a goofy, mildly raunchy cabinet card photo in which Abbéma is dressed as an Ottoman pasha and Bernhardt, in the diaphanous costume of an Ingres odalisque, lies at her feet, mooning up at her lasciviously. So Draw Your Own Conclusions.

Not that any of this bisexual coupling, one might add, Herr Doktor, ever kept those nasty Goncourt brothers from gossiping about Bernhardt’s ‘untuned piano’ – namely, her Supposed Sexual Frigidity. Bernhardt got married only once, disastrously, in 1882: to the hulking and brutish Jacques Damala, a Greek diplomat and actor with a monster morphine addiction – a sort of Missing Link type. While lampooned in Parisian high society as Monsieur Sarah Bernhardt and La Damala des Camélias, he was also rumoured, paradoxically, to be the only man who could bring the Dionysiac damsel to the peak of sexual satisfaction. The union was thankfully brief: Damala was cold, diseased, and so sinister, apparently, that Bram Stoker claimed to have used him as one of the models for Count Dracula. He died at 34 from a drug overdose, much mourned by Bernhardt, then in her mid-forties. Fortunately, she soon found solace elsewhere – if never again the pinnacle of feminine happiness – with other more chivalrous swains.

More, Herr Doktor – there is yet more:

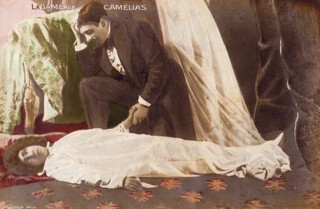

6. The Playful Necrophilia. Oh, yes: Ordering Her Own Coffin and Sleeping in It. Gottlieb isn’t sure if she really slept in the coffin, or just pretended to for the publicity. (The notorious fake post-mortem photo from 1880, showing the actress stretched out, eyes closed, and clutching a bunch of lilies to her bosom, seems to have resulted, royalty wise, in many happy returns for both her and the Paris society photographer Melandri.) Sarah likewise thoroughly enjoyed her thousands (literally) of on-stage death scenes. These were protracted and often acrobatic. In an ancient three or four-second YouTube clip of her as the dying Marguerite (a role she played at least 3000 times) she makes an astonishing 360° death-twirl into the arms of her leading man, then, stiffening like a board, falls full-length to the floor. She’s like a diver doing a perfect corkscrew: everything clean and neat in the replay, no splash anywhere.

Hardly surprising that jokey publicists satirised her during one of her American tours as ‘The Great French Dier’ and rated some of her best ‘dies’ (‘The Adrienne – a rich and lasting die of strong solid colour shot with poison streaks’; ‘The Sphinx – a crawly sensational die … Has fine green lights and foamy variations’ and so on). Gottlieb thinks that this predilection for the morbid and sensational was an essential part of Bernhardt’s fairly ruthless and weird psychic make-up. She relished the macabre and in fine old Baudelairean fashion visited the Paris morgue to get clues on how best to feign rigor mortis. As one of her many admirers, the critic Jules Lemaître, somewhat alarmingly observed: ‘She becomes herself only when she’s killing or when she dies.’

7. The ‘Exotic’ Half-Jewishness. Bernhardt’s mother, Youle, was Jewish, but with an eye to her daughter’s prospective future as upscale courtesan, she had had Bernhardt baptised a Roman Catholic in childhood. Bernhardt also attended a convent school and often claimed to be a simple pious Catholic girl. But to her credit – even when mercilessly Jew-baited in the French right-wing press (some of the cartoons and caricatures of her in the 1880s and 1890s are as grotesque as anything produced by Nazi propagandists a few decades later) – Bernhardt never dissembled on the subject of her ancestry. She defended Zola passionately after the publication of ‘J’accuse’, and carried on, impervious, when performances she gave in Russia provoked anti-semitic riots in Kiev and Odessa. (Sad to read the nasty loaded comments, quoted by Gottlieb, from one of one’s erstwhile literary heroes: Turgenev derided her ‘repulsive Parisian chic’ – so ‘false, cold and affected’. Later on, Gottlieb notes, the American Gilded Age novelist William Dean Howells ‘dismissed her Hamlet as a triple impertinence: not merely French and feminine, but Jewish as well’.) Andy Warhol, among others, seems to have been intrigued by the Jewish Bernhardt. In his gorgeous (and curiously undersung) silkscreen series Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century (1980), Bernhardt, Gertrude Stein and Golda Meir are the three stately ladies in the series, ranged alongside Einstein, Kafka, the Marx Brothers, Gershwin, Martin Buber, Louis Brandeis and, ahem, you, Herr Doktor.

8. The Obsessive-Compulsive Globetrotting. As her fame grew, Bernhardt was seldom at home. She was the inverse of agoraphobic; seems to have lived most of her life, in fact, in a sort of high-pitched fugue state, performing everywhere from Oslo to Istanbul, Cairo to Wichita, Sydney to Buenos Aires, Montreal to Mombasa, Munich to Tahiti. She toured the US nine times, always in a womb-like, lavishly appointed personal train. (Son Maurice, plus various boyfriends, inevitably accompanied her on these junkets – complete with repeat visits to chic little spots like Grand Rapids, Iowa City and Lincoln, Nebraska. She even gave a recital in a small and rackety Gold Rush theatre, now a private residence, just down the street from where I live in San Francisco.) The fortune she acquired by touring was immense. Yet she also seemed to supercharge, rather than deplete, her formidable life-force by means of this ceaseless ocean-hopping. She relished her American fans in particular and tore up the house (however provincial) everywhere she went.

9. The Bizarrely Cathected-On Pets. Besides a Pekinese and an Airedale, the private Bernhardt menagerie – which sometimes travelled with her – included an alligator, a tiger cub and a lion cub, a full-sized boa constrictor, flocks of tropical birds in cages, and the odd lynx. ‘The most fascinating of the pets,’ the artist W. Graham Robertson wrote, ‘was the lynx, a really lovable beast … affectionate as well as graceful: the mysterious white-robed figure of Sarah coming down the steps into her studio with the lynx gliding noiselessly beside her was so suggestive of Circe that one looked about for the pigs.’ So embarrassing: one’s own pet lynxes, one must confess, are not even toilet-trained yet.

10. The Sartorial Perversions. Few competitors here. On stage and off, Bernhardt was the epitome of Art Nouveau style at its most kinky and outré – a human equivalent of a Guimard Métro station or one of Gaudi’s more surreal flights (that hideous Palau Güell, perhaps). Witness the swathes of velvet and exotic silks, Hittite princess bangles, ultratight corsetry, Sacher-Masoch furs (including a floor-length, outrageously padded chinchilla coat), garnet-studded tiaras, the famous Hat Crowned with a Stuffed Bat. (In choice of costume, on stage and off, Eleonora Duse, Bernhardt’s one female rival on the early 20th-century stage, was nun-like by comparison.) Cheesy historicism: a Great-Sarah speciality. To prepare for the role of Théodora, she travelled to Ravenna to examine the Byzantine mosaics of the empress in the church of San Vitale. One result of this search for authenticity was that towering, ‘double-eagle crown, studded with real amethysts, opals and turquoises’ in which she subsequently posed, half-nude, for a series of smouldering publicity photographs.

Nor, Herr Doktor, should one omit to mention:

11. The Notorious Cross-Dressing and (hélas!) Increasingly Obese Drag Turns. However much the femme fatale in life and art, Bernhardt also had a Serious Trouser Fetish. On stage, she seemed almost to prefer being a man – usually the handsome young male lead. Among the celebrated breeches parts: Hamlet, Cherubino, Pelléas, Lorenzaccio, the troubadour Zanetto in Le Passant, Judas, Werther and (yikes) Shylock. Later in life her favourite male role, first assumed when she was a portly 56-year-old, was that of Napoleon’s tragically shortlived son, the Duke of Reichstadt, in Rostand’s drama L’Aiglon. (Gottlieb observes that her costume in this part – a pale, stretchy-smooth, Spandex-like hussar outfit – made Bernhardt look unfortunately like a pouter pigeon. A pouter pigeon, one might add, with a sort of Chateaubriand hairdo.)

Bernhardt was convinced that, psychologically speaking, she was better at playing fey young men than fey young men were:

A woman is better suited to play parts like l’Aiglon and Hamlet than a man. These roles portray youths of 20 or 21 with the minds of men of 40. A boy of 20 cannot understand the philosophy of Hamlet nor the poetic enthusiasm of l’Aiglon … An older man … does not look like the boy, nor has he the ready adaptability of the woman who can combine the light carriage of youth with the mature thought of the man. The woman more readily looks the part, yet has the maturity of mind to grasp it.

The young duke was meant to be 17 in the play; so Bernhardt’s performance was ‘mature’ in every sense, if not gnarly with knobs on.

All of which reflected exquisitely –

12. The Hysterical Exhibitionism. Bernhardt was the first non-royal celebrity to market her own image on a truly international scale. She was a self-brander – like Madonna or Lady Gaga – avant la lettre. Painters and sculptors and designers flocked to her. Canny advertisers – especially in America – clamoured to use her picture on trade cards and soap packaging. Virtually every other ‘vintage’ postcard or trade card now to be found on eBay is a picture of Bernhardt. The early Nadar studio portraits were haunting – some of the Sarony photographs too – but what about all those icky Art Nouveau posters by Alphonse Mucha? Ugh. The actress as pagan goddess: aloof, hieratic, with curly vine-tendril hair and surrounded by acid-trip lettering. (One used to encounter reproductions of them in every hippy head shop in the world in the late 1960s. Thus one’s inability to see one now without getting a phantom whiff of patchouli incense and hearing Santana chugging away somewhere in one’s head.)

And finally, Herr Doktor, how could one forget, towards the end of her life:

13. The Symbolic Castration – i.e. The Amputated Leg? Having hurt her right leg on stage in Rio de Janeiro in 1905, Bernhardt aggravated the injury by continuing to keel over in death swoons, engage in flashy swordfights and otherwise stomp about on the boards for ten more years. (Playing a fat, freakish, almost mummified-looking Elizabeth I in her wildly popular 1912 silent film Les Amours de la reine Elisabeth, she has a noticeable limp and is visibly in pain.) The limb had to be cut off above the knee in 1915. (P.T. Barnum supposedly offered to buy it for $10,000 so he could exhibit it.)

Bernhardt, it must be said, bore dismemberment stoically. She refused to wear a prosthesis and instead had herself carried around on an elaborate litter. She continued to act – imperiously, from the litter, supported by footmen in appropriate costumes – and indeed followed a punishing professional schedule up until her death in 1923. Only a few weeks before she died, she was still hard at work, filming scenes for a silent movie version of her young protégé Sacha Guitry’s play La Voyante (‘The Fortune Teller’). There’s a terrifying, almost ghoulish, photograph of her from one of these shoots in which she sits at a table in dark glasses, false teeth plainly extruded, hamming it up as an ancient sibyl for the poor fellow (in a fedora, no less) who’s come to have his fortune told.

Nor did she cease to exhibit – in this fabled last phase – a Truly Rapacious Demand for Unconditional Love. Throughout the First World War she orchestrated elaborate patriotic fêtes and, like a trouper, took them everywhere, even to the edge of the battle zone. She played for French poilus returning from the Western Front; she exhorted audiences at home and abroad to contribute to the Allied war effort; she invigorated the Parisian multitudes with her dramatic recitations of the ‘Marseillaise’. Her undisguised one-leggedness proved a stark bond with many of the war’s grievously wounded survivors. ‘She could not be gainsaid,’ Janet Flanner, the acerbic Paris correspondent for the New Yorker, wrote some years later,

as a magnificent if mutilated theatrical relic. The last thing we all saw her in was L’Aiglon, in which with great dignity she rose on one remaining limb from her chair and, holding herself firm with one hand, swung her arm into the theatrical air to salute France as Rostand’s young leader who never led or ruled. She always had a bleating voice. Paris never heard the like of it again until the country fell under the rule of Marshal Pétain. Whatever Pétain said in his public speeches to listening France had the tremolo of Bernhardt’s vocalisation, though of course he never said as she so often did in her most melodramatic scenes: ‘Je t’aime! Je t’aime!’

Bernhardt’s funeral procession through the streets of Paris in 1923, Flanner recalled, ‘was such a sight for flowers, followers and fanaticism as hadn’t been seen here since Victor Hugo’s obsequies, and wasn’t to be seen again till Anatole France was laid to rest with equally handsome blossoms but some less fragrant political pamphlets’.

There you have it, Herr Doktor: a Freudian cornucopia! Such An Overripe Banana-Fest one hardly knows where to start! Put Sarah on the couch at once! And Palin too while you’re at it!

Until, of course, one remembers: a banana – ceci n’est pas exactly une pipe. Or even un cigare. The Reality Principle reasserts itself; the imp-brain is forced to power down. For in spite of the engorged and engrossing Bernhardt legend – the vast piles of memorabilia, the gossip and grandiosity, the vapour trail a million miles long – the Lady in Question is nowhere to be found, let alone supine and confessional on one’s kilim-draped daybed. Analyse Sarah Bernhardt? One might as well try to analyse Phèdre or Andromaque. Devoid of inwardness, a self-invented creature of myth and feints and hard repelling surfaces, Bernhardt would have resisted one’s analytic wiles. Despite a life of astounding incident she was also a magnificent fortress raised against introspection.

Granted, a handful of witnesses in her own time – you’re tempted to call them conscientious objectors, so heroically resistant to her hokey spell do they now appear – recognised the problem from the start: the emotional void at the core, the monster-sized Bernhardt tease. The ‘childishly egotistical character of her acting’, George Bernard Shaw observed,

is not the art of making you think more highly or feel more deeply, but the art of making you admire her, pity her, champion her, weep with her, laugh at her jokes, follow her fortunes breathlessly, and applaud her wildly when the curtain falls … And it is always Sarah Bernhardt in her own capacity who does this to you. The dress, the title of the play, the order of the words may vary; but the woman is always the same. She does not enter into the leading character: she substitutes herself for it.

And yes: one does get a sense with Bernhardt of such aggressive, gold-bangle fakery: her greedy, unabating, if also weirdly refulgent, projection of sovereignty. She made everyone a citizen of her rackety old country – or tried to.

Which leaves a conscientious biographer in a bit of a pickle. What to do with a subject – especially a major historical subject – who seems to lack a grown-up interior life? Who offers little but stagey poses, a hand languidly flung to brow, or a lot of specious business with a handkerchief? A century on, it’s as if Bernhardt were still daring us to make sense of her. On one side: the plethora of exotic, still exfoliating detail, too much really to comprehend in a single narrative, a limitless archival excess. (Bernhardt, one is forced to admit, takes up more laminated pages – in one’s own modest little carte postale collection, that is – than Liane de Pougy, Pavlova, Duse, Lillie Langtry and Cléo de Mérode put together.) And on the other: the emotional impenetrability; the sense of chilly, inhuman, surface-of-the-moon-style emptiness. The Divine Sarah looms up, floods us with TMI (trop d’information, as the Académie française would have us say) and yet somehow in the doing makes herself utterly cold, posthumous and unknowable.

Gottlieb – a former editor of the New Yorker – does as well as anyone could in such tricky, sticky circumstances. His new biography is suave, intelligent, always slyly entertaining, though also at points a tiny bit underpowered, a little Johnny-come-lately in feeling. The quality of belatedness was perhaps unavoidable: a century’s worth of Bernhardt biographies precede this one, after all – in English as well as French – and some of them have been superb. The redoubtable Cornelia Otis Skinner – American stage actress and author of the sublime Our Hearts Were Young and Gay – wrote a boffo if now somewhat dated biography for English readers in 1967 entitled Madame Sarah. (In the requisite Mucha-decorated dustjacket, it became a supermarket bestseller in the US in that long-ago Summer of Love.) And the prolific biographer and novelist Ruth Brandon produced another excellent life in the 1990s.

My own favourite Bernhardt book is Robert Fizdale and Arthur Gold’s The Divine Sarah (1991): an epic yet intimate jaunt through Bernhardt’s career that catches both the camphor-soaked seduction and gloriously channelled neurosis. The fact that Fizdale and Gold were a celebrated (also gay) American piano duo of the 1950s and 1960s – virtuosic together in anything from Mozart to Poulenc and John Cage – seems oddly relevant here. Yes, it required the two of them to take Bernhardt on, rhetorically speaking; yet partnered thus, they also had between them enough nervy gay boy wit and fleet camp dexterity to keep the Divine One from blowing everybody’s circuits.

While always companionable, Gottlieb, by comparison, can appear somewhat depleted and risk-averse. Especially when it comes to capturing the legendary Bernhardt excess – professional, artistic, amatory, sartorial, self-promotional, financial – he is inclined to take short cuts and to refer us back to previous biographers. And at times he seems to sigh, almost audibly, over-certain of his subject’s less ladylike doings. He admires her in some wise, to be sure (and surely she must have possessed some unaccountable zest) but he also comes across at times as slightly bored, as a slack, possibly jaded boulevardier: Maurice Chevalier in dusty straw boater twinkling over Gigi one more time, except the Gigi here is a frizzy-coiffed ballbuster named Bernhardt.

Gottlieb can hardly be faulted for not solving the Sarah ‘problem’ when even the canniest of her contemporaries (Freud included) found themselves unmanned by her. Some of them, too, were unwomaned. In 1908, in one of the oddest, twistiest and most ambivalent word-portraits of the actress ever made (and one of the few major English commentaries unnoted by Gottlieb), a precocious and no doubt foolhardy Virginia Woolf came a cropper too. The occasion was the publication of the English translation of Bernhardt’s first – and only – volume of memoirs, Ma Double Vie from 1907. Woolf, intriguingly, chose to review the book in the ‘Book on the Table’ series in the Cornhill Magazine. A somewhat lopsided match: Bernhardt was 63 and world famous; Woolf, a late blooming 26-year-old, was just beginning her public literary career.

A generation, not to mention an enormous emotional and aesthetic gulf, separated the two women. But incongruous as it sounds – a bit like imagining Nadine Gordimer clubbing, say, with Lindsay Lohan – it’s a pretty good bet that Woolf would have seen Bernhardt on stage. Unless I’ve missed it, none of the Woolf biographers reports such an encounter, but Woolf would have had dozens, if not hundreds, of opportunities to see Sarah Bernhardt in the flesh before 1914. (Relishing the acclaim she extracted from British audiences, who seemed to go gaga over her even when they didn’t understand French, Bernhardt made annual artistic pilgrimages to London for several decades.) Adding to the likelihood that Woolf saw her: the fact that the budding novelist’s Bloomsbury milieu was so heavily populated with male homosexuals – Bernhardt’s natural fan base – and that Woolf’s great friend Lytton Strachey was one of the Frenchwoman’s most fervent English acolytes.

It’s a sublimely strange essay, as much for what it says about Woolf as for what it says (or doesn’t say) about Bernhardt. For, not to put too fine a point on it, the piece is quite spectacularly incoherent. Woolf begins it with what she hopes, rather too optimistically, will be taken as a truism by her reader: that the memoirs of a great actress must inevitably elicit ‘an unusual interest and excitement even’, precisely because of the putative distance between the roles the actress plays on stage – her generous enactment of ‘this passion and of that’ – and the independent life that she resumes, or so we like to imagine, as soon as the curtain falls and the greasepaint is removed. Thus even as the actress ‘lives before us in many shapes and in many circumstances’, Woolf writes, she also ‘sits in passive contemplation some little way withdrawn, in an attitude which we must believe to be one of final significance. It might be urged that it is the presence of this contrast that gives meaning to the most trivial of her actions, and some additional poignancy to the most majestic.’

Now this passage is peculiar enough: as if Woolf, in the act of watching a play, were seeing two manifestations – two avatars almost – of the actress simultaneously. There, at the front of the stage, immediately before us, is the flesh and blood woman performing her ‘role’. But somewhere upstage, off to one side, perhaps, is the actress’s ‘real’ self – conceived here as a detached spectral intelligence, calmly monitoring the action from an oblique vantage-point. Woolf displays a possessive, rapt, almost erotic interest in this secondary phantom observer. For though ‘some little way withdrawn’, the actress’s spectral double turns out to be a kind of presiding maternal spirit. Aloof, dispassionate, reticent, she nonetheless subtly shapes every detail of the performance.

She is, in fact, that quintessentially Woolfian figure: the pensive, lovely, quietly regal woman-in-charge. Mrs Ramsay in To the Lighthouse, placidly knitting a sock while she rules like a queen over her rambunctious family circle, will be a full instantiation of the type; similarly, Clarissa Dalloway, dreaming, judging, analysing, animating – managing, ever so delicately, the lives of everyone around her – even as she snips off the flower stems and mends a green silk dress for her party.

The problem is that Bernhardt – dreadful powdery old thing – is nothing like Mrs Ramsay or Clarissa Dalloway. (Or indeed Virginia Woolf.) ‘Perhaps no woman now alive could tell us more strange things, of herself and of life, than Sarah Bernhardt,’ Woolf writes hopefully. We – that is, the memoirist’s readers – long for her to ‘show us what cannot be shown upon the stage’. But since recounting ‘strange things’ is exactly what the actress omits to do in My Double Life (her title notwithstanding), Woolf’s intricate opening gambit – the idea of the two-part ‘self’ – has nowhere to go. No meditative ‘second self’ emerges; no secret inwardness is brought to light.

True, Woolf tries gamely to hide her irritation. She never says in so many words that she finds Bernhardt boastful, robotic and inhuman. But her ambivalence, verging at times on intellectual disgust, is palpable. So slick the Bernhardt power of mimicry, Woolf allows, that even when ‘the alien art of letters is used to express a highly developed dramatic genius, some of the effects that it produces are strange and brilliant’. But certain other effects – confusingly – ‘pass beyond this limit and become grotesque and even painful’. We confront, Woolf argues, a ‘hardness and limitation’ in the actress’s method, and her book finally ‘wearies’ us with its ‘multiplication of crude visible objects’. However scientifically exact, her stage impersonations are ‘the productions of a very literal mind’.

Woolf would later project some of the dislike she displays here onto those stick-figure puppet characters in her fiction who share Bernhardt’s mental and emotional void and refuse to present (or are incapable of presenting) any ‘inside’ to others, even when such intimacy is demanded. One wonders if the seductive and cartoonish Russian princess Bernhardt played in Fédora, for example, doesn’t have something to do with Sasha, the equally seductive and cartoonish Russian princess in Orlando: the sex-changing hero’s faithless inamorata and an empty shell of a character if ever there was one. Sasha cross-dresses with aplomb (as of course does Orlando): on first sighting Orlando believes her to be a boy. Hard not to wonder if Woolf might not have taken at least a few hints for both characters, as well as from Shakespeare, from Bernhardt en travesti.

Woolf’s essay ends with a Freudian nightmare (as will this one). Describing Bernhardt-the-memoirist’s relentless, exhausting assertion of ‘personality’, Woolf compares the reader, thus assailed, with a ‘creeping’ and ‘bewildered animal, whose head, struck by a flying stone, flashes with all manner of sharp lightnings’. Thus stunned, ‘it is possible, as you read the volume’ – and none of this sounds very pleasant –

to feel your chair sink beneath you into undulating crimson vapours … in which some vivid conflict goes forward between bright pigmies; the clouds ring with high French voices perfect of accent, though so strangely mannered and so monotonous of tone that you hardly recognise them for the voices of human beings. There is a constant reverberation of applause, chafing all the nerves to action. But where after all does dream end, and where does life begin? For when the buoyant armchair grounds itself … with a gentle shock that wakes you and the clouds spin round you and disappear, does not the solid room which is suddenly presented with all its furniture expectant appear too large and gaunt to be submerged again by the thin stream of interest which is all that is left you after your prodigal expense?

After the squeaky ‘mannered’ pigmies and ‘nerve-chafing’ clamour, the banality of everyday life reasserting itself disorientates us. Head-spinning, to be sure, that one must once more ‘dine and sleep and register one’s life by the dial of the clock, in a pale light, attended only by the irrelevant uproar of cart and carriage, and observed by the universal eye of sun and moon which looks upon us all, we are told, impartially’.

So we are told, but just here, in a few wonky and disastrous final sentences, Woolf suddenly goes – well, a bit mad. Having resisted the Bernhardt lamia-spell up to this point, the sceptic now abruptly concedes. Sun and moon are not so impartial, after all. For aren’t we all, she inquires, ‘in truth the centre of innumerable rays which so strike upon one figure only, and is it not our business to flash them straight and completely back again, and never suffer a single shaft to blunt itself on the far side of us?’ Bernhardt shoots it out, her giant phallic lighthouse beam; we are there to reflect it back.

Dr Schreber in the worst throes of paranoia, or indeed a homeless woman convinced that aliens are speaking to her through her dental fillings, could not have put it more frighteningly. ‘By reason of some such concentration’ – some warping of the light rays, one infers – Sarah Bernhardt ‘will sparkle for many generations a sinister and enigmatic message; but still she will sparkle, while the rest of us – is the prophecy too arrogant? – lie dissipated among the floods.’

Now it is never reassuring to see Woolf, later to arrange her own death by water, unconsciously rehearsing her demise and lying ‘dissipated among the floods’. But is her prophecy otherwise correct? It is now well over a hundred years since Sarah Bernhardt first trod the boards. By the time of her own death in 1923 she was already hopelessly out of date. Woolf the modernist and her colleagues by then held the stage; the 20th century was well on its way to unfolding (if not already pretty far gone). Bernhardt was by contrast one of the last living monsters of the 19th century. She sounds perfectly awful, but I am aware that thinking thus may be my post-post-post 21st-century bias showing.

The press recently marked the death of the last known British survivor of the First World War. And likewise at some point – a decade ago? less than that? – the Last Person Who Saw Sarah Bernhardt on Stage must have died. Woolf is wrong, one might venture with some relief: the ‘forgetting’ of Bernhardt must surely now go on apace – the forgetting, that is, of a lot of greed, bad faith and mummified human drama. The great thing about so-called Performance Art is that after a certain date no one is around to remember it – all those vanity-stagings of L’Aiglon. Already Bernhardt is getting tinier – tinier, even, than pigmy-sized. She’s now just a flickery, antiquated, one-inch-high YouTube shadow, there amid the screen clutter for a second or two, blinking and tottering and apparently squawking. Adieu, madame – and not a moment too soon.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.