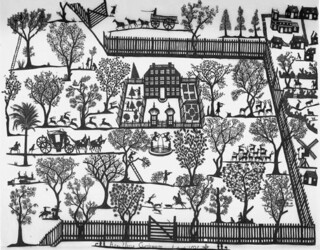

In contrast to the still contentment of a Zoffany conversation piece or the energetic racket conjured up by Fielding’s novels, life indoors in Georgian England was frequently a dull, hard and miserable business. For those who did not fit the norms, social or material, the outcome was often exceedingly uncomfortable. As Amanda Vickery writes in Behind Closed Doors, her sparkling, richly detailed investigation of what she calls the ‘hazy background’ to the Georgian household, ‘cruelty begins at home.’ She looks at many types and conditions of person throughout the long 18th century, but the picture is never sharper than when she focuses on those men and women who by accident, of fate or of birth, did not have homes of their own.

In her reading of documents ‘against the grain’, Vickery finds a great deal of information about everyday life, much of it previously hidden. ‘Access to privacy,’ she notes, ‘was an index of power.’ Her examining of records from the Old Bailey brings to light the formerly blanked-out domestic detail of rough lodging houses and servants’ quarters. The testimonies offered in cases of breaking and entering tell of scant furnishings and pathetic possessions. The paltry interiors of cheap lodging houses are described in detail for the benefit of the court; a rented room in a house off a Hampstead yard contains three beds, in continual use by a parade of lodgers. The last one to leave ‘takes a bit of padlock, and locks the door, and takes the key down, and hands it in the kitchen’. One landlord, suspicious of a locked door, bores straight through the wainscot. When he has secured himself a clear view into the room, he sees that his suspicions were justified: the quilt has gone. In such a house, keys had an emblematic as well as a practical function, closing off or providing access to a plethora of cupboards, caddies, drawers, secret compartments and imaginatively hidden closets. Servants, confined to attic or cellar, would be fortunate to have enough possessions to fill a locked box.

Higher up the social scale, in less straitened material circumstances, it wasn’t only women whose prospects could be uncertain. The domestic sphere of the bachelor of the ‘middling sort’ was an uneasy place, a kind of limbo in which he lingered in the anteroom to matrimony. If he stayed there too long, he might find nobody in the room beyond, and many a bookish tutor or shy curate never even reached the threshold. The countryside was full of fusty scholars waiting for clerical preferment, incubus-like figures who remained in the orbit of a family for life. The creepy Ralph Bohun hung around the Evelyns for 40 years until finally achieving his prize, the living at Wotton, by which time his tactless interference in their personal lives had forfeited him the affection of the family.

Once the typical bachelor or, sometimes, widower had successfully identified a suitable mate, the later stages of courtship decreed that he must energetically gear himself up to the marital state. His bride would expect him to present a more sociable face to a wider world, to act at ease in mixed company, and to improve everything from his manners to his taste to fit her aspirations. In all likelihood, this would involve a new house, the marital home, or at least a decorative clean sweep, forcing him to consider such previously irrelevant matters as the choice of furnishings in a fashionable style. One cleric saw some ‘pretty papers’ at his neighbour’s house and ordered the same pattern himself, writing to Joseph Trollope & Sons, wallpaper suppliers: ‘I care nothing about fashion if they are neat & clean.’ If a man was facing marriage he was likely to find his purse under pressure; the strings could be tightened later on but at this stage it was politic to err on the side of generosity. At least he knew, as the Lancashire curate Thomas Brockbank did, he would soon be relieved of that ‘many footed Monster house-keeping’.

Men who lived alone tended to be more articulate and revealing about their domestic needs and routines than their married counterparts, a fact Vickery uses to considerable advantage. Dudley Ryder, the son of a City of London linen-draper, ‘flew free on a guy rope of family money’, as Vickery puts it, and pursued a fast and easy life as a law student (eventually rising to the heights of his profession). He lived in the Temple but returned home to Hackney for a decent meal and introductions to girls judged more suitable than those he was suspected of meeting in town. Time at home unfailingly brought him face to face with his parents’ many shortcomings, so back he would head to his serviced chambers and the joys of independence.

Nearby, a worthy Anglican cleric-to-be, John Egerton, was lodging in Lincoln’s Inn. He furnished his rooms with a rug, bureau, clock and piano, only to find that he had seemingly mislaid his fine and valuable linen sheets. After months of wrangling he became convinced that his housekeeper had stolen them. Since Mrs Pitt was living under the same roof, and thus could not be prosecuted for house-breaking, he decided to dismiss her. At this point he surprised himself, finding how well he could manage, buying in cold cuts of meat and eating out at one of the many institutions (medical, legal or collegiate) that supplied the needs of men like him, independent and far from home. But the episode demonstrated to Egerton the urgency of his hunt for a wife, his need for a person who could be depended on to organise his domestic life and, above all, his sheets: one area of home life to which, oddly, men seemed completely unequal, frequently writing home to their mothers for advice about the purchase, laundering and care of the contents of the linen cupboard.

Bachelor quarters tended to be, in Vickery’s words, ‘more lair than headquarters’ and few can have hunted longer or more fruitlessly to find a congenial aide-de-camp than John Courtney, a Yorkshire gentleman who had already inherited his late father’s estate. Despite his wealth, he unsuccessfully proposed no less than eight times. Once he finally reached the altar, in his mid-thirties, a wedding tea was held. Courtney proudly put out his best agate knives for the occasion; they had been carefully stored away for many years. He was finally home.

‘To keep house with ye Man we love must be preferable to any other state, if that love be mutual,’ a Suffolk spinster mused, realising that it was a state she herself would never attain. For the maiden lady, her claim to a home was ‘no less significant an idea for being a memory’ or simply an unrealistic but invaluable illusion which she kept well hidden, except in the intimacy of her journal. Such a woman was wise to have relatively few possessions, a trunk or two and a few items of portable furniture, since on the death of a parent she was liable to be shunted out of the family home, often to the back regions of the house of a reluctant sibling. Perhaps inevitably these women, less accepted in society and by their families than widows, wrote prolifically about their unhappiness. Gertrude Savile’s subjection to her brother’s will was ‘henbane’ to her and she dealt with her inferiorities (being plain, motherless, unmarried and poorly educated were just a few of them) by noisy retreat into the pages of her diary. The furious spinster took refuge: ‘Entirely confine myself to my room … work’s chair very hard. That, and my Cat all my pleasure.’ Any woman who stood at the head of a busy household, following a steady daily routine, carrying a heavy bunch of keys and, ideally, enjoying the ‘silent satisfactions of conjugality’, found no call, and had absolutely no time, for such outpourings.

Marriage is a ‘union of difference’, Vickery writes, and even in courtship the divisions of responsibility between the sexes were already being decided on. Though one relaxed bride-to-be reported that her fiancé was quite prepared to take a house ‘in any part of the Town that I like’, another threw herself into the role of clerk of works at the future marital home: ‘I sent for Mr Pickering who promis’d to send his Men in very early o’ Monday morning but we have again differ’d in opinion a little.’ A third recent bride steadfastly refused to move from Essex to Coventry. Undaunted, her ambitious older husband carried on fitting up their future home, rather to further his career ambitions than to suit the needs of a family. Choosing the wallpaper for the staircase – ‘a Stucoe pattern’ – he kept a beady eye on the expense, ensuring that it was not hung any further up the stairs than could be seen from the first-floor landing, the limit to any visitor’s tour. But he hadn’t reckoned with his physically frail yet utterly resolute wife. Mrs Hewitt dug her heels in and refused to ‘live eight months in a year without you … in a place where I have not one single friend of my own to speak to’. It was years later when she and her children finally moved to join their father, entirely on her terms.

Undeniably, the best protection for the spinster, the widow or the spurned or misunderstood wife was wealth – along with a measure of determination. A woman such as Anne, Duchess of Grafton, at least initially more sinned against than sinning, used these to her advantage. Faced with her husband’s multiple infidelities, she took a strong moral line and carried on a full social life at her own handsome town house – even continuing to use the ducal livery. It was only when she herself fell in love that her privileges were withdrawn; fortunately for her she had, once again, landed in a comfortable place.

There was a more surprising happy landing for Gertrude Savile, who had sat for so long alone in other people’s houses, her needle flying furiously on yet another beautiful piece of needlework, ‘my most elligant Divertion, and all I shall ever be fitt for’. She gained financial independence overnight from an entirely unexpected bequest and became a wealthy woman, living in her own London town house in Great Russell Street. She had little time or motive to keep a journal any longer.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.