Poor Europa! The competition to give her an ancestry has been raging for generations. Now the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford – the new, gorgeously refashioned Ashmolean, which reopened last November with 39 new galleries – has joined in.*The Lost World of Old Europe reveals a brilliant, imaginative, precocious culture that arose in south-eastern Europe in the late Neolithic period, the Copper Age, but after flourishing for several thousand years, failed and was forgotten.

This show, which comes from New York and will eventually move on to Athens, is the first big exhibition to use the museum’s new spaces. I never really knew the unreformed Ashmolean, and I retain only the impression of an overcrowded, loveable depository of jumbled treasures: Grand Tour marble torsos nudging cases of Chinese porcelain, vases from Knossos, Italian violins, paintings from Uccello to Gainsborough, intricate dead clocks. Like Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, the Ashmolean was its own exhibit: a museum to display an essentially 18th-century collectors’ museum.

That’s all gone. Behind the mighty old façade, the new design is more like MoMA in Manhattan. Piranesi with the lights on. Glass corridor-bridges spanning the abyss of a vast atrium, crow’s-nest windows that allow you to look from one gallery into another on a different floor. It’s exciting. The idea is that visitors can make unexpected visual connections, and the slogan of the redesign is ‘CCCT – Crossing Cultures Crossing Time’. But there is a problem here, a time-bomb for architects and curators. If you fashion a museum building to fit a display strategy, what happens when the display strategy changes? Let’s say that a cunning window in the Chinese gallery on the fourth floor allows people to see into the Hellenistic gallery on the third floor and grasp the cultural (CCCT) connections between them. What happens in 20 years’ time (about the life of any display strategy) when ideas about the past change and curators decide that China and Greece have nothing to do with each other, and that the true connection is, say, between China and the Persian empire? Do you then have to knock the whole building apart and reorient its architecture? The new Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh will face the same problem. Sometimes I think that the best museum design is just an enormous shed, with movable partitions.

The postwar search to give amnesiac Europa a pedigree shows how fickle ideas about past connections can be. There was the Celtic Europe craze, once much favoured in Brussels. This imagined an Iron Age continent which was already a union of related languages and cultural styles. This notion culminated in the grand I Celti exhibition in Venice in 1991, but soon withered under academic criticism. Then came the passion for the Bronze Age. If Europe didn’t start as a political union, then maybe it was founded as a trading bloc. Couldn’t we imagine a vast Free Trade Area, in which amber, gold, copper and tin circulated in a customs union reaching from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, from the Dnieper to the Atlantic? More recently, the dwarfish hominid skeletons from Dmanisi in Georgia – thought to be early Homo erectus, some 1.8 million years old – have been promoted as ‘the First Europeans’. Their loudest promoter was President Chirac, determined to keep France in the van of intellectual Euromania. But even the French have failed to prove that, when the Dmanisi folk emerged from Africa, they turned left for Paris. They may just as well have hung a right for Tehran or Kabul.

Now comes ‘Old Europe’. The Oxford exhibition is small, but utterly spectacular. Its objects – the figurines, the painted ceramics – are irresistible. Its message adds a new page to the conventional history of ‘civilisation’. Some 7000 years ago, in south-eastern Europe around the lower Danube, groups of farmers with loosely similar ways of life settled in an area reaching from modern Bulgaria and Romania across into Ukraine. In the transitional period between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, they flourished and multiplied. They evolved an elaborately beautiful material culture of painted pottery, goldwork and beads. They modelled and treasured clay figurines of women – and a few men. They mined copper and gold, and imported fashionable seashells from the distant Aegean. They seem to have lived in peace and equality. Before the first big cities arose in Mesopotamia, the peoples settled between the Carpathians and the Dnieper (heftily named the ‘Cucuteni-Tripolye culture’) lived in enormous ‘villages’ with up to 8000 inhabitants. These were the largest communities anywhere in the world. But such ‘megatowns’ show no trace of palaces or temples or other structures of central authority. If this ‘Old Europe’ had survived and spread westwards and northwards, the human story of the whole continent might have developed along a different track – perhaps a happier one.

But it did not survive. ‘Old Europe’ became a ‘Lost World’. Between 4000 and 3000 BC, invaders rode in from the eastern steppes, mobile warriors who used horses and who were pastoral herders rather than farmers. The mounds (‘tells’) inhabited for thousands of years were deserted and the ‘megatowns’ burned down. The copper mines were abandoned and the wonderful pottery and figurines forgotten. So much for theories of inevitable, linear progress. In Europa’s family tree, there is a sawn-off branch.

Archaeologists have known about ‘Old Europe’ for a long time. At first, they studied the pottery and the statuettes, and classified them into ‘cultures’. But it took them longer to move on from the objects and to grasp the extraordinary nature of the society that produced them, to understand this immensely remote ‘false dawn’ of authentic European civilisation. The Cold War isolation of the countries where it all happened – Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Ukraine – has meant that until now the general public has never seen this material.

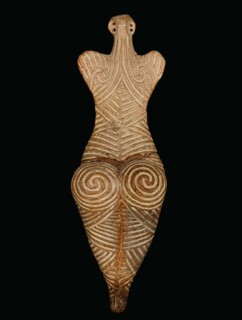

The figurines are the stars of the show. Almost all of them are the stylised bodies of women, their legs squeezed tightly together, their heads often represented by a blank knob, their thighs and sometimes torsos incised with swirly patterns which seem to represent clothing. In some of the sets of Cucuteni figurines, the women are sitting in a circle on tiny chairs. At another site, they were found arranged inside a curious bowl which may represent a building. They seem to be holding a meeting.

What are they up to, and what is going on? The late Marija Gimbutas, who introduced the ‘Old Europe’ term, was sure she knew. They were mother goddesses, worshipped in a peace-loving society run by women. Reaching into her own background in Lithuania, the last pagan country in Europe, she identified a White Goddess of Death and all the deities of a maternal fertility cult. According to Gimbutas, this ancient matriarchy was finally overthrown by an invasion of primitives from the Black Sea steppes, horse-riding tribes dominated by male warriors. Agriculture, the earth-loving mode of life practised by women who controlled fertility in a society without hierarchy, was replaced by the male activities of stock-breeding, raiding and battle under dominant warlords.

Gimbutas, a professor of archaeology at UCLA, became wildly popular with the American womens’ movement in the 1970s and 1980s. Her books (starting with The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe in 1974) inspired feminists and neo-pagans throughout the world. But other archaeologists backed away. They found her conclusions arbitrary, her associations with other cults far-fetched, her selection of evidence wilful. Where was the proof that these societies were controlled by women? Why should the figurines be goddesses worshipped in some Greek-style pantheon, rather than something humbler? Peter Ucko, the late director of the Institute of Archaeology at UCL, thought that the statuettes were probably just toys or dolls. The American scholar Douglass Bailey, writing in the exhibition catalogue, finds them intensely moving, but guesses that making them mattered more than using them. Experiments have shown that fashioning or handling tiny representations of reality slows up the sense of time passing and sharpens perception. So the women (and men?) who modelled these figurines were finding a way to stand outside themselves, to study their own membership of their community.

Wandering from one showcase to another, I noticed that a fair minority of the figurines are in fact male. Unlike the women, they are naked except for a girdle and sometimes a shoulder holster, perhaps for a dagger. They sprawl on their chairs with their legs apart, showing what they’ve got. And yet the fact that the men are a minority among regal women – this is far more suggestive than if they were not there at all. Tolerated, but not in charge? Maybe Gimbutas had something after all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.