This exhibition is an attempt to represent the work of one of the most long lived of British artists, whose career began in the aftermath of Culloden in 1746, and ended only six years before the Battle of Waterloo. As a teenager, through the influence of his elder brother, Thomas, himself a gifted artist and architect, Paul Sandby was taken on as a military draftsman for the Board of Ordnance, producing reliable maps for use in the subjugation of the Highlands. By the time of his death, his astonishing industry had earned him many years of genteel prosperity, selling his original drawings and paintings, publishing collections of his prints, taking on private pupils, and teaching at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. But in the last years of his life he suffered from continual anxieties about money. His style had become unfashionable, and his efforts to change it – to become more picturesque, more European in manner, somehow more obviously a heavyweight – seem to have led nowhere. The last picture in this show, a woodland scene with a rainbow, part Hobbema, part Rubens, is certainly heavy, but it is a sad coda to a career that had been based on deftness, on lightness of touch.

Living so long, and exerting the influence he did over the development of watercolour, Sandby was described, when he died, as the ‘father of modern landscape painting in watercolours’. At a time when landscapes in watercolour, together with landscape gardening and mezzotint engraving, were probably the only areas of visual art in which Britons were generally persuaded that they could beat the competition from abroad, to be the father of landscape painting in watercolour was a kind of patriotic identity, even though it would come to be denied that painting in watercolour was what he did. And as the title of the exhibition suggests, Sandby’s art was thoroughly patriotic, in an understated way. ‘He has formed a style peculiarly his own, and peculiarly English,’ one contemporary wrote. His landscapes, superbly drawn, brightly but beautifully coloured, celebrated both Britain’s past and its present, the evocative ruins of abbeys and castles, the thriving towns and bustling turnpikes, trees so ancient that the Normans might have planted them, a race meeting at Ascot, landscape gardens in the latest style and still under construction. They are, as the exhibition repeatedly demonstrates, very much more than attractive images of Happy Britannia, but they are gorgeously, seductively attractive.

Sandby was extraordinarily prolific: nobody could begin to say how many thousands of his pictures have survived, and how John Bonehill, the curator of this exhibition, decided on his final selection I can’t imagine. Sandby was also enormously versatile: he worked in watercolour, bodycolour (gouache) and oil, he etched, he was the first professional artist in Britain to work in aquatint, in which he became as near perfect as can be imagined. As well as an artist of landscapes and townscapes, he was a caricaturist and the maker of many informal portraits, he issued a series of ‘Cries of London’ and he did much more.

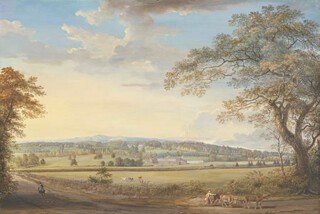

Landscape, however, was his central preoccupation, and it is the landscapes that make the most exciting showing at the Academy. Though he worked in Scotland as a boy and a young man, and later pioneered the tours of Wales that became such a standby for artists in search of the picturesque and sublime, his real heartland was – at least on the showing of this exhibition – the Home Counties: Windsor, Virginia Water, Luton Hoo, the country round Basingstoke and round Maidstone, where he produced extensive, undulating panoramas and occluded views of ancient woodland. At Luton, he became fascinated by the beech trees, some of them with vast contorted trunks and giant limbs, one coppiced and then neglected, to grow up like an inverted banyan. At Windsor, he produced a series of beautiful images of the different tasks involved in woodland management that could be illustrations for an 18th-century georgic poem on the subject. At Englefield Green near Egham, where his son had a villa, he made landscapes of the family amusing themselves in their garden and entertaining their guests, in idealised images of Georgian middle-class domesticity and sociability. Many of these images are much more complex than at first they seem, but the first sight of Sandby’s England, where the sun always shone and winter never came, is simply and honestly delightful.

But the sunny brilliance of Sandby’s art was clouded well before his death by an account of his work which, while not necessarily denying his abilities, even his genius, consigned him to a lower rank among artists because the subjects he chose to represent were claimed to be unworthy. When, in the 1760s, the Earl of Hardwicke attempted to commission Gainsborough to paint a view for him, the artist replied:

Mr Gainsborough presents his Humble respects to Lord Hardwicke; and shall always think it an honor to be employ’d in any thing for his Lordship; but with regard to real Views from Nature in this Country, he has never seen any Place that affords a Subject equal to the poorest imitations of Gaspar or Claude. Paul Sanby is the only Man of Genius, he believes, who has employ’d his Pencil that Way – Mr G hopes Lord Hardwicke will not mistake his meaning, but if his Lordship wishes to have any thing tolerable of the name of G. the Subject altogether as well as the figures &c must be of his own Brain.

In this intriguing response, Gainsborough, who was still far from establishing himself among the elite painters of late 18th-century Britain, nevertheless makes it clear to Lord Hardwicke that he wishes to be regarded as a candidate for promotion to the premier league. He is not a servant painter; he has no eagerness to cater to the mistaken taste of a patron whatever the title he bears or the price he offers. He demands respect for the quality of his imagination, of his invention, and wishes to be compared with the great names of Italian landscape art, an ambition that would be compromised if he were to agree to paint views of real places in a country where the landscape is so obviously second-rate. Gainsborough of course loved the English countryside, as a place to walk in, to sketch in, perhaps to retire to – but not as a subject for painting. Individually, the hills, the trees, the roads, the ponds of England might be perfectly paintable, but only when reorganised into structures imagined by the artist’s ‘own Brain’. The name for an artist who would agree to paint the real places, however tame or scruffy, that Hardwicke’s ignorance might lead him to admire, was ‘Mr Sanby’. Sandby, Gainsborough concedes, is nevertheless a man of genius, but he seems to be pretending to believe that only in order to claim the same status for himself: among us men of genius, he implies, only Sandby is sufficiently obedient or mercenary to do what no man of genius should ever do.

By the end of the century, the cultural cringe towards France and Italy that led Gainsborough to claim that the landscape of Britain, or at least of England, was unworthy of representation, was a thing of the past. Before his death, Sandby’s success would be claimed to be based on the ‘frequent contemplation of this variety of scenery, a variety with which Great Britain abounds’. But that did not stop theorists of high art disparaging artists who painted ‘real Views from Nature’ in this or any other country. The (to me unknown) author of a long article on painting published in the Encyclopaedia Britannica in the 1790s wrote of the 17th-century Dutch landscape painters – he is thinking apparently of artists such as Hobbema, or Jacob van Ruisdael – that they have

no rivals in landscape painting, considered as the faithful representation of a particular scene; but they are far from equalling Titian, Poussin, Claude Lorrain, &c. who have carried to the greatest perfection the ideal landscape, and whose pictures, instead of being the topographical representation of certain places, are the combined result of every thing beautiful in imagination or in nature.

And a few years later, Henry Fuseli, speaking in his capacity as professor of painting at the Royal Academy, told the students in the Academy schools that, among the ‘uninteresting subjects’ of art which they should take care to avoid, was

that kind of landscape which is entirely occupied with the tame delineation of a given spot; an enumeration of hill and dale, clumps of trees, shrubs, water, meadows, cottages, and houses; what is commonly called Views. These … may delight the owner of the acres they enclose, the inhabitants of the spot, perhaps the antiquary or the traveller, but to every other eye they are little more than topography. The landscape of Titian, of Mola, of Salvator, of the Poussins, Claude, Rubens, Elzheimer, Rembrandt, and Wilson, spurns all relation with this kind of map-work.

Fuseli did introduce a small saving clause in defence of painters of ‘Views’: their ‘enumerations’ of the objects in a scene become ‘little more than topography’ only if they are not ‘assisted by nature, dictated by taste, or chosen for character’. But this does little to protect Sandby and others like him from the charge of being more cartographers than artists, for every ‘view’, in the opinion of whoever is making a picture of it, is chosen with taste and chosen for character. Obviously, the only proper option for a landscape painter of ambition is to make it up.

From one point of view, opinions like these look like the last gasp of a notion that art must represent an idealised nature if it is to take us above and beyond the quotidian, the commonplace, the merely ‘real’. Was there ever an artist more devoted to English views than Constable? Had there ever been an artist more intent on painting them with all the minute fidelity that would appeal, according to Fuseli, only to the landowners and inhabitants of those places? By the mid-19th century, the notion that landscape artists should invent the scenes they painted looked like a recipe not for ‘high art’ but for idleness or cheating. Landscapes were to be painted as nature (supposedly) had designed them, with a better taste and more invention than any artist could pretend to; the artist’s imagination was to be looked for in the ability to make views atmospheric, poetic, by capturing the ‘effects’ on places of light, weather and season. Fuseli’s pejorative description of ‘views’, and those who made images of views, as merely ‘topographical’, had attracted few adherents earlier in the century, but now, just when the ‘faithful representation’ of particular scenes became a categorical imperative of landscape painting, it caught on, and ‘topographers’ were zealously distinguished from true artists concerned with ‘effects’. In part perhaps this was a response to the invention of photography, and offered a means of distinguishing the most effect-ful paintings of landscape from the soulless images photography could be accused of providing.

The time bomb under Sandby’s reputation now at last went off. In a fascinating essay in the exhibition catalogue, Felicity Myrone, curator of topography at the British Library, and thereby hangs a tale, shows how the label attached to the images she is charged with curating was fastened to Sandby even by his admirers, a term that managed to appear at once innocently descriptive and a mark of inferiority. Samuel Redgrave, in his biographical dictionary of artists first published in 1874, remarked that Sandby ‘did not get beyond topography and the mere tinted imitation of nature’; of Francis Jukes, on the other hand, Sandby’s friend and the engraver of some of his works, Redgrave wrote that he ‘began art as a topographical landscape painter, but by great perseverance raised himself to much distinction as an aquatint engraver’. Better to be an engraver than a mere topographer; better to copy (with distinction) the works of other artists than to copy, supposedly no doubt without ‘effects’, those ‘real Views from Nature’. Myrone quotes a review of a book on Sandby by his great-great-nephew William, which describes the artist as ‘struggling to free himself from tradition, which was topographical’, whereas an artist like Tom Girtin or Turner had ‘got free, and was turning his wings in the open, which was landscape’. For all this, the reviewer continued, Sandby ‘contributed much to the reputation of English landscape, and paved the way for more illustrious successors’. For Martin Hardie, writing in the 1940s, Sandby was ‘the last, as he is the greatest, of the topographers’: ‘He was not an original artist like Turner or Cozens; he was of his age and gave it what it liked and could understand … The rapid development of watercolour … left no longer any room for such an art as Sandby’s. The antiquarian and the connoisseur, topography and landscape art, were cast as opposed and incompatible.’

These accounts of the place of topography in the history of watercolour all derive from, and all misread, an immensely influential series of essays on ‘The Rise and Progress of Watercolour Painting in England’ by the artist and writer William Pyne, published in his short-lived periodical, The Somerset House Gazette, in 1823 and 1824. At its simplest, the story Pyne told was of a major shift in the use of the medium at the end of the 18th century. Earlier makers of landscape in watercolour made ‘tinted drawings’, first drawing their outlines, shading them through in black or grey, and finally ‘staining’ or ‘tinting’ them. The most distinguished practitioner of this method, for Pyne, was Sandby, ‘whose memory is regarded with veneration by the present school’. His importance now, however, was that he had laid a foundation for a practice of watercolour painting that had made his method obsolete. The modern school, Turner, Girtin and their followers, had worked like painters in oils, ‘laying in the object … with the local colour, and shadowing the same with the individual tint of its own shadow’. ‘It was this new practice … that acquired for designs in watercolours upon paper, the title of paintings.’

In the same series of essays, Pyne distinguished between the ‘topographical’ and ‘landscape’, whether in tinted drawings or in true watercolour paintings. For him, whether the views represented by artists were ‘real’ views of particular places was of no particular importance, and though he presumed that ‘topographical’ images were of real places, it did not follow that ‘landscapes’ were expected not to be. Topographical images were pictures of ‘abbeys, castles, ancient towns, and noblemen’s seats’ and suchlike, that when represented in ‘tinted drawings’ appealed especially to those with antiquarian tastes. Landscapes were images where the main interest was in rural scenes in which buildings were incidental or at least not the primary object of attention.

For Pyne, landscape and antiquarian topography were equally worthy subjects, and he took to task those who mistakenly believed that topographical subjects ‘did not afford sufficient scope for the display of much talent’. Girtin and Turner had shown that they could be treated with the same degree of ‘original feeling … beauty of detail, variety of tones, elegant touch, breadth of effect and general harmony’ as landscape subjects. Whether by inattention, however, or deliberately and with their own agendas, those writers like Redgrave, William Sandby, Hardie and numerous others who took over Pyne’s distinction between ‘tinted drawings’ and ‘watercolour painting’, conflated it with a division between topography and landscape which they presumed to be his but was in fact their own. This enabled them to associate topography – by which they meant landscape short on ‘effects’ – with tinted drawings and the followers of Sandby, and to represent them as all obsolete, second-rate and now fortunately superseded by landscape, watercolour painting and the followers of Turner. As Myrone points out, it was when supposedly topographical art came to be thought of as ‘mere’ topography that the vast collection of views and landscapes in the British Museum was split: what the 19th-century keepers decided was ‘art’ went into the Department of Prints and Drawings at the museum; what they branded as ‘topography’ was relegated to a kind of ‘salon des refusés’ in the library, where, exactly as Fuseli would have wanted, it is now kept with the maps in what has become, in spite of all, a thoroughly fascinating and enriching collection of images.

And still today historians of art by and large use the words ‘topography’ and ‘topographical’ to refer to views of named places in graphic media – prints, drawings, watercolours – which apparently can’t be claimed to be somehow more than topographical. It seems that in using these terms they believe they are following 18th-century practice; that in the heyday of Sandby and what is called the ‘topographical tradition’, views of real places were distinguished from ideal landscapes by being described as ‘topographical’. I believed this myself until a few weeks ago, when it occurred to me to start researching the word on various online databases which contain a huge selection of 18th-century books, pamphlets and newspapers. I also searched the Gentleman’s Magazine online, as the general interest periodical most hospitable to readers with an interest in ‘topography’. These online searches, especially of the invaluable ECCO – Eighteenth-Century Collections Online – can be irritating because from one day to another the results they throw up can be oddly different. I’m not a very sophisticated user of such databases, and maybe there’s a way of regulating them so that they don’t duplicate results or omit results one day that they had included the day before. One way or another, however, searching ECCO from 1751 to 1800, when it stops, and the newspapers and the Gentleman’s Magazine till 1810, the year after Sandby’s death, I have had, in three separate searches over a fortnight, a total of between 2000 and 3000 hits for ‘topographical’. Sad I know, but that’s what life is like for the semi-retired.

Altogether, and after stripping out the repetitions (repeated advertisements in newspapers, reprintings of books), I had only 33 results, barely one every two years, in which the adjective ‘topographical’ qualified a noun that had anything to do with picture-making. A few of these referred to the kind of military drawings, of fortifications or profiles of contours, that Sandby taught his pupils to make at the Royal Military Academy. Most of the time the adjective was used more or less as Pyne used it, in connection with images of old buildings of antiquarian interest. In a very few cases it is possible, though on the whole unlikely, that the word refers to views of ‘real’ landscapes which are not, primarily, the setting for some kind of ancient monument. Only in the encyclopedia entry I quoted earlier did it clearly do so. Advertisements for books of engraved views, of the kind Fuseli would have disparaged, frequently promised ‘topographical descriptions’ of places to accompany the prints, but I have yet to find such an advertisement that described the views themselves as topographical.

When we describe Sandby’s art as topographical, we probably think we are meeting it on its own terms, or in the terms of his own time; but in fact we are using the word in a sense in which it was barely used in his lifetime, and which, when it came to be applied to his work in the later 19th century was intended not simply to identify its genre but to indicate its supposed limitations. If we still choose to refer to his landscape images as ‘topographical’, and to see him as belonging to a ‘topographical tradition’, we need to be careful of importing into the discussion of his pictures assumptions about the nature of landscape art which, if they were made more explicit, we would probably choose to disown. Myrone, who probably has slightly more faith than I do in the existence of that tradition, suggests that if we continue to use the term we should do so with a more ‘expansive sense’ of what topography meant in the 18th century, and we could see that as exactly the aim of this exhibition.

‘Topography’ was a genre of literature, at least of writing, not of visual art, and opinions on what it was and should be about differed sharply. Some writers championed a more ‘expansive’ sense by which it comes close to many of the modern meanings of the ‘geography’ of a place, including its natural features, its settlements, its agriculture, mineral resources, communications, industry and commerce, its institutions, its history as expressed in the relics of its past, old buildings in particular but also surviving legends and customs, and so on. In practice, however, many of those who claimed to be ‘topographers’ worked with a much narrower agenda, concentrating very largely on archaeological and architectural remains, the genealogies of noble and gentry families, and their mansions. The liberal Dissenter John Aikin and the radical poet John Thelwall protested about this: we turn to topographers to learn ‘the real condition of the people’ and what we find instead is a kind of antiquarianism designed to flatter ‘the great men who have proud mansions in those neighbourhoods they describe’, concentrating on the history of posh houses and posh families to the exclusion of ‘circumstances more universally interesting’. The notion of ‘topographical’ art that we find in Pyne comes closer to this second, antiquarian notion. If Sandby’s art can be described as ‘topographical’, however, in an 18th-century sense, it seems to be so especially when it moves beyond the walls of the landscape park and looks at what was happening in the towns and the countryside of late 18th-century Britain, as it grew more prosperous, more commercial, more ‘modern’.

That we can see it in this way is very much due to the work of Stephen Daniels, the original proponent of this amazing exhibition, and one of its co-curators. Daniels is a cultural geographer, who in a series of essays on individual works by de Loutherbourg, Turner, Constable and others, including Sandby, has introduced a way of understanding the landscape art of late 18th and early 19th-century Britain in which the places depicted are shown as contested sites, places over which different interests assert incompatible claims, where the past and present compete for attention, where the local is at odds with the national, where values are affirmed because somewhere else they are being called into question, where different versions of what Britain should be grind against each other. In this way of reading them, images of landscape don’t have anything so reassuring as a ‘meaning’; their disparate elements are just about – or not quite – held together by a visual rhetoric that invites us to believe that these antagonisms might somehow be balanced or blended by composition, by the harmonious arrangement of colours, or by that relation of near and far that artists called ‘keeping’.

One of the highlights of the current exhibition is Sandby’s panoramic view, shown here, done in bodycolour and watercolour on Whatman paper, of the house and factory of the manufacturer of that paper near Maidstone in Kent. An evening in late autumn; a country house and park set in obviously productive farmland; a neat model factory tucked into a river valley; in the foreground, under a spreading ash tree, a milkmaid drives a few cows along a country road, to or from milking; a farmer trots away from us; and in the near distance a stagecoach is passing a dozen or so stacks of hop-poles. The first time I saw this picture it seemed to me a perfect evocation of the peace and plenty of georgic Kent, and a perfect example of what made Sandby such an attractive artist. Then, in the first sentence of an essay on the picture, published in 2006, Daniels announced that it displayed ‘the scope and intensity of 18th-century topographical art’. ‘Scope’? ‘Intensity’? I was soon persuaded, however, as Daniels demonstrated how much more there was in this delightful image of cherry orchards and hop-gardens; what the elms stripped of their lower branches, what the exposed chalk on a far distant hill, what a dozen other features of the landscape were contributing to the range of issues to which the image was responding; how they helped specify its relation to highly politicised arguments about the nature of the picturesque, about the value of panoramic views, about the place of commerce in the present and future prospects of Britain, and to the endangered position of the Garden of England as the front line in the event of an invasion by the armies of the French republic, already so menacingly successful in north-eastern France. It is helpful and precise to describe this kind of image, read this way, as ‘topographical’: at once comprehensive and acutely specific about the nature of a particular place, understood in its relation to the wider cultural, economic, political geography of the nation.

In the exhibition catalogue, Daniels, the exhibition curator, John Bonehill, and Nicholas Alfrey develop this way of understanding Sandby’s landscapes in a panoptic summary of his career spent ‘Picturing Britain’, and it is extended in some of Bonehill’s immensely observant catalogue entries on individual works.* If the exhibition takes off from Daniels’s understanding of Sandby, the bulk of the writing in a strikingly informative as well as gorgeously illustrated catalogue, is Bonehill’s. As well as Felicity Myrone’s very thoughtful piece on Sandby and topography, there are fine essays too by Martin Postle on the Sandby brothers and the Royal Academy, and by Geoff Quilley on Sandby’s satires against Hogarth, etched with a bitterness and grotesquerie that seem to go beyond Hogarth’s own. Bonehill and Sarah Skinner provide a helpful short essay on the inexhaustible issue of Sandby’s techniques and the materials he used.

Perhaps the most intriguing essay in an exceptional catalogue, however, is by Matthew Craske, on Sandby’s many images of Windsor. Many of these are perfectly finished architectural drawings of the castle and its terrace of a kind to delight the 18th-century amateurs of antiquarian topography. There is one image in particular, of the Lower Ward of the castle looking from the base of the round tower, which seems magical in its ability to find an apparently unstressed order in the higgledy-piggledy clutter of architecture within the castle precinct. But what particularly fascinates Craske is how Sandby took the opportunity in his images of Windsor to represent the inhabitants of the place in a series of small satirical portraits and encounters. Often dwarfed by the grandeur of the castle, they are on too small a scale to call attention to themselves, but, once noticed, they turn out to depict repeated collisions between ‘supposedly refined townsfolk and a dirty transient population attracted by their prosperity’. A drunken vagrant, a wounded soldier reduced to begging, a night-man collecting door-to-door the faeces of polite families, all situate the place and its pretensions within a reality so mundane that Royal Windsor will never seem quite the same.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.