Earlier this year, I visited the Birmingham suburb of Bournville for the first time. Planned and developed by the Cadburys in the 1890s, the estate is explicitly modelled on an ideal of the English village, with the mostly semi-detached houses playing a set of variations on the theme of the cottage. Consulting Pevsner as I walked around, I was surprised to find that, normally rather sniffy about the various forms of imitation and revival that make up most modern English domestic architecture, he was almost enthusiastic about the style of these placid, unambitious dwellings. ‘Gradually,’ he noted of the growth of the Bournville development, ‘a few satisfactory basic types of house were evolved to suit the way people want to live.’

Driving out of Birmingham later that day on the peculiarly modern nightmare that is its inner ring road, I found myself returning to that last, uncharacteristic phrase: ‘to suit the way people want to live’. How could one know that this was the way people wanted to live; rather than, say, the life they’d more or less unwillingly adapted to? Looking out of the car window, I would have had to conclude that a great number of people want to spend much of their time driving in and out of Birmingham on a badly designed racetrack bordered by establishments that will fit a new exhaust on your car while-U-wait, sell you a leather three-piece suite for nothing (at least, nothing today), or stuff your family with a day’s worth of unnutritious calories for less than a tenner – all of them housed in structures whose pedigree is, at best, out of warehouses by sheds. My Ruskinian moment passed, but it was a reminder that cultural critique always relies on some idea of the way people ought to want to live, something that can’t simply be inferred from looking out of the car window.

Bournville, J.B. Priestley declared after his visit there in 1933, ‘is one of the small outposts of civilisation, still ringed round with barbarism’. Taken in isolation, the remark is superior and windily apocalyptic. But isn’t that true of much ‘Condition of England’ writing, always finding portents of aesthetic vulgarity and moral squalor in a handful of carefully selected examples? Traditionally, the genre hasn’t allowed much standing to ‘the way people want to live’, and if that remark was representative of Priestley’s contribution, then English Journey seemed likely to confirm my impression of him as a predictable and not very interesting writer. But the truth about both this book and its author, and perhaps about the genre as a whole, turns out to be more complicated.

Born in Bradford in 1894, Priestley, after extensive service in the First World War and three years at Cambridge, had embarked in the early 1920s on the precarious career of a man of letters, turning his hand to criticism, essays and novels, all written in haste, none enjoying much success. The income from a collaborative work with the much better known Hugh Walpole enabled him to embark on a more ambitious third novel, The Good Companions, published in 1929. Its huge sales, together with those of Angel Pavement the following year, transformed his life. He became wealthy, sought after by publishers, loved by a wide readership and reviled by Bloomsbury. When he succeeded to Arnold Bennett’s reviewing pulpit in the Evening Standard in 1932, it confirmed his place as the spokesman for what was sometimes denigrated as a plain-mannish or middlebrow taste for social realism. As the literary hot property of the moment, a writer firmly identified with both ‘the North’ and ‘the people’ (the two were hard to distinguish when seen from literary London), he seemed to his publishers to be the ideal figure to take the national temperature at the depth of the Slump. English Journey, published the following year, was the result. It, too, was an immediate success – displacing Thank You, Jeeves at the top of the bestseller list – and was reissued several times during Priestley’s life (he died in 1986). Here was a version of Cobbett’s Rural Rides for the age of the motorcoach.

The travel narrative as cultural criticism has a distinguished history, stretching from Defoe and Cobbett up to Iain Sinclair and Bill Bryson. In the 19th century, such writing was overlain by a style of critique that was less topographical and more frankly ethical or existential: extended essays on what a few carefully chosen examples of contemporary crassness and complacency revealed about the moral quality of the culture as a whole. The great names here, whom Priestley admired, included Carlyle (who coined the term ‘Condition of England’), Ruskin, Arnold and Morris. In the closing decades of the 19th and the early years of the 20th century there were several related attempts, by writers such as Richard Jefferies and Edward Thomas, to identify ‘England’ with ‘the countryside’ (largely for an urban readership), while the interwar decades tended to throw up more quizzical searches for ‘the real England’, assumed to have been submerged by the shoddy detritus of ‘progress’ and requiring the skills of the then fashionable figure, the anthropologist, for its proper identification and recovery. H.V. Morton’s bestselling In Search of England (1927) was English Journey’s immediate predecessor, a whimsical attempt to locate the ghosts of nobler ages in surviving relics and ruins. Its best-known successor was, of course, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), an account of the degrading squalor in such ‘depressed areas’ as Wigan and Barnsley, and an indictment of the callousness and self-deception that enabled the comfortable classes to ignore such appalling conditions.

Out of fashion today, Priestley may not seem to belong in this company, and I have to admit that I came to English Journey expecting sentimental uplift mixed with anecdotal illustration of the claim that there’s nowt so queer as folk. There is a certain amount of that, but it’s far from being the whole story. The rumination on Bournville encapsulates the book’s strengths and weaknesses, not least because of what it says about the tension for cultural criticism between the claims of how ‘people want to live’ and how people ought to want to live.

For the most part, Priestley was impressed by what he saw in Bournville. The Cadburys’ plan, he acknowledged, had ‘proved very successful’. The dwellings and public spaces were ‘infinitely superior to and more sensible than most of the huge new workmen’s and artisans’ quarters that had recently been built on the edge of many large towns in the Midlands’. He regretted that they were all detached and semi-detached: it would have been less ‘monotonous’ had there been more terraces, quadrangles and so on, ‘but I was assured by those who know that their tenants greatly prefer to be semi-detached.’ That, it seems, was the way people wanted to live. Those of them who were employees at the chocolate works also seemed to want to live in the Cadburys’ pockets:

Their workpeople are provided with magnificent recreation grounds and sports pavilions, with a large concert hall in the factory itself, where midday concerts are given, with dining-rooms, recreation rooms, and facilities for singing, acting, and I know not what, with continuation schools, with medical attention, with works councils, with pensions … Once you have joined the staff of this firm, you need never wander out of its shadow.

So here were ‘nearly all the facilities for leading a full and happy life’. What’s more, the firm insisted that no compulsion was involved, and it ‘never moves to provide anything until it knows that a real demand exists’. The workers were getting what they wanted, and it was a lot better than most workers got elsewhere.

Nonetheless, Priestley couldn’t help feeling a bit uneasy about the workers’ sunny compliance with this generous paternalism. He noted that when the Cadburys tried to offer the same benefits to employees at a new factory in Australia, they ‘met with a decided rebuff.’ The Australian workers wanted to get away from the shadow of the works and provide their own amusements, and though they may as a result have been worse off materially, ‘it is clear,’ Priestley concluded, ‘that the Australian employee as a political being is occupying the sounder position.’ Here the question of ‘the way people want to live’ becomes more complex: the English employees, it seems, wanted one way, the Australians another. Priestley’s view of ‘the sounder position’ provoked him to a little riff on the ‘spirit of independence’ that can make him sound like the sternest Victorian moralist, even a latter-day civic humanist. All this paternalist provision, he wrote, created ‘an atmosphere that is injurious to the growth of men as intellectual and spiritual beings’. Almost before you know it, a visit to a chocolate factory has turned into the occasion for a sermon on ‘character’ and on the moral dignity of the ‘free citizen’. ‘I for one would infinitely prefer to see workers combining to provide these benefits, or a reasonable proportion of them, for themselves, to see them forming associations far removed from the factory, to see them using their leisure, and demanding its increase, not as favoured employees but as citizens, free men and women.’

But, this being so, the sense in which he regards Bournville as ‘one of the small outposts of civilisation’ can’t be altogether straightforward. What he admires about it is not just that the architecture and layout of the estate are superior to the jerry-built barracks of other suburbs, but also that it is ‘neither a great firm’s private dormitory nor a rich man’s toy, but a public enterprise that pays its way’. In effect, the ethical quality he admires in Bournville the estate is the opposite of the ethical quality he deplores in Bournville the works: the former embodies a healthy relation between independence and co-operation, the latter an unhealthy one between paternalism and contentment. But what if, more generally, provision of ‘the facilities for leading a full and happy life’ is inimical to fostering the ‘spirit of independence’ rather than favourable to it? Would England be better or worse if it were one big Bournville?

As one reads on in English Journey, these tensions come to seem structural rather than confined to this case. At the conclusion of his tour, Priestley reflected that he had discerned three Englands: ‘Old England’, the ‘England of the Industrial Revolution’ and ‘Postwar England’. Definition by enumeration, a familiar trope of this genre, has issued in some memorable, and rhetorically effective, lists: think of Orwell’s in The Lion and the Unicorn, which runs from ‘the clatter of clogs in the Lancashire mill towns’ to ‘the old maids biking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn morning’, or Eliot’s in Notes towards the Definition of Culture, which moves from ‘Derby Day, Henley Regatta, Cowes’ through ‘Wensleydale cheese, boiled cabbage cut into sections’, and on to ‘19th-century Gothic churches and the music of Elgar’. Priestley, looking to differentiate his ‘three Englands’, mostly focuses on what can be seen through the window of the motorcoach.

The first England is gestured at in perfunctory terms: ‘the country of the cathedrals and minsters and manor-houses and inns, of Parson and Squire; guidebook and quaint highways and byways England … We all know this England, which at its best cannot be improved upon in this world.’ While he makes clear that he is all for ‘scrupulously preserving the most enchanting bits of it, such as the cathedrals and the colleges and the Cotswolds’, he also recognises that there can be no ‘going back’ to the way of life represented by these enchanting monuments.

Then there is 19th-century England:

the industrial England of coal, iron, steel, cotton, wool, railways; of thousands of rows of little houses all alike, sham Gothic churches, square-faced chapels, Town Halls, Mechanics’ Institutes, mills, foundries, warehouses, refined watering-places, Pier Pavilions, Family and Commercial Hotels, Literary and Philosophical Societies, back-to-back houses, detached villas with monkey-trees. Grill Rooms, railway stations, slag heaps and ‘tips’, dock roads, Refreshment Rooms, doss-houses. Unionist or Liberal Clubs, cindery waste ground, mill chimneys, slums, fried-fish shops, public houses with red blinds, bethels in corrugated iron, good-class drapers’ and confectioners’ shops, a cynically devastated countryside, sooty dismal little towns, and still sootier grim fortress-like cities.

Although ethical appraisal starts to intrude before the end (‘cynically devastated’, ‘dismal’), this is by and large a list of material, mainly architectural objects – the Lit and Phil Societies, like the Liberal Clubs, get in for their buildings. The period is characterised by what is most visible to the modern traveller, not by its ideas and social practices except as implicitly embodied in these artefacts. But the very exuberance and excess of the list indicates something like affection: although these sights may not all be objectively beautiful, they start to sound not merely familiar but treasured. This is the England in which Priestley grew up, and it clearly still tugs at his emotions.

The list he chooses to represent the third England, the England of the post-1918 years, aspires to offer something similar, but social criticism short-circuits the description at an earlier stage:

This is the England of arterial and bypass roads, of filling stations and factories that look like exhibition buildings, of giant cinemas and dance halls and cafés, bungalows with tiny garages, cocktail bars, Woolworths, motorcoaches, wireless, hiking, factory girls looking like actresses, greyhound racing and dirt tracks, swimming pools, and everything given away for cigarette coupons.

This is not only a shorter and notably cooler list, but it also includes a higher proportion of activities to buildings, bespeaking a sharper edge of social criticism. This was the Americanised England Priestley, in his early middle age, saw taking over, and the curl of the lip is palpable.

He is adamant that it makes no sense to think of ‘going back’ to the first England, and, for all his admiration for aspects of industrial England, he regards it as on the whole a ‘wrong turning’, a condition where ‘money and machines are of more importance than men and women.’ Yet the England that has succeeded it he clearly considers ersatz and shallow, as cultural critics nearly always judge contemporary life to be. Some of the dividedness that characterised his reaction to Bournville is detectable on a larger scale here: he acknowledges that the third England is ‘a cleaner, tidier, healthier, saner world than that of 19th-century industrialism’ and that these are important improvements. But maybe it’s a bit too clean, too tidy: the improved sewerage that now carries away the more plentifully available bathwater risks carrying off some irreplaceable babies. ‘I cannot help feeling that this new England is lacking in character, in zest, gusto, flavour, bite, drive, originality, and that this is a serious weakness.’ So where is his ideal ‘England’? If it is projected into the future, as the radical strain in Priestley suggests it should be, then it looks as though it would have to combine the beauty and tranquillity of the first, the vigour and independence of the second, and at least the positive aspects of the democracy and widespread prosperity of the third.

This is a familiar mix, characteristic of that strain in English sensibility from the late 19th to the late 20th century which combined (among other things) social progressivism and a love of old churches. Priestley is not a medievalising romantic, certainly not any kind of agrarian fundamentalist, and he disclaims Golden Ageism in robust terms. But, as with so many writers in this tradition, these disclaimers do not mean that certain kinds of nostalgia aren’t at work in his responses. In so far as he has a consistent target it is, in true Carlylean or Ruskinian vein, industrialism rather than capitalism. And, as with Ruskin, the politics of the eye predominate. He is revolted by squalor and ugliness, but less acute about those forms of injustice that are structural and whose effects are not readily visible. In the same way, his method relies on portrait and anecdote rather than on economic history and sociological analysis. The focus of his critique of contemporary society appears to be ‘standardisation’ not exploitation. In his anxiety that the people are losing their ‘natural vigour’, he can sound like an antique moralist.

At the same time, part of the appeal of the book comes from the way the writing exhibits a knowing sense of its own charms. On the first page, taking the motorcoach to Southampton, Priestley rhapsodises on the luxurious comfort of this relatively new means of transport and concludes: ‘They are voluptuous, sybaritic, of doubtful morality.’ The author of English Journey is the winking raconteur who allows his audience to see him enjoying his own rhetorical ornaments, like a rug merchant theatrically unrolling an old Baluch. From time to time he even stages a moment of inner conflict to show us what a human fellow he is. More generally, there is nothing pinched or chilly about Priestley’s prose, nothing guarded or finicky. There was good reason for him to be compared to Dickens, or at least to one strain in early Dickens, though these affinities also suggest the qualities that have attracted charges of cosiness and sentimentalism.

One of the staples of this style of social criticism involves citing a complacent and celebratory announcement of the country’s prosperity and good fortune by some official or public person, and juxtaposing to it a pointed instance of actual squalor and misery. Matthew Arnold had milked this device in ‘The Function of Criticism’, exhibiting the fatuity of politicians’ eulogies on national greatness when placed alongside a news report of a young workhouse mother in the Mapperley hills driven to murder her illegitimate child (‘Wragg is in custody’). English Journey contains several such set-pieces, the best-known being his visit to the street he calls ‘Rusty Lane’ in West Bromwich at the end of his tour of Birmingham and the Black Country. Part of Priestley’s popularity lay in his readiness to pull out the emotional stops. He was not frightened of the hackneyed or obvious. Thus, his visit to Rusty Lane has to take place in ‘foul weather’: ‘the raw fog dripped … it was thick and wet and chilled.’ The street is no ordinary hell: ‘I have never seen such a picture of grimy desolation as that street offered me.’ Local urchins throw stones onto the warehouse roof while he is visiting: he understands why they do it. ‘Nobody can blame them if they grow up to smash everything that can be smashed.’ Then he cranks the handle on his portable moraliser:

There ought to be no more of those lunches and dinners, at which political and financial and industrial gentlemen congratulate one another, until something is done about Rusty Lane and West Bromwich … And if there is another economic conference, let it meet there, in one of the warehouses, and be fed with bread and margarine and slabs of brawn. The delegates have seen one England, Mayfair in the season. Let them see another England next time, West Bromwich out of the season. Out of all seasons, except the winter of our discontent.

He isn’t proposing a policy: he has no idea what kind of ‘something’ needs to be ‘done’. The intention is, instead, to puncture the thick skin of unawareness that allows the comfortable classes to maintain their habitual moral indifference when surrounded by suffering and injustice. Yet it is the depressingness of the scene as much as the underlying injustice that has provoked this little cadenza; we’re left feeling that ‘something’ needs to be ‘done’ about that dripping ‘raw fog’ while they’re at it. If only those eminent gentlemen could be brought here to see this, the rest would follow. And the closing trope could hardly be more hackneyed.

English Journey avoids the structural cliché of terminating at Jarrow (we ease down the east of England and on to the continuing civic vigour of Norwich), but it is certainly the case that its account of the North-East contains some of his most memorable writing, weeping for a people ‘without work or wages or hope’ – ‘I had seen nothing like it since the war.’ Today it may seem that it took no great powers of observation or sympathy to feel outraged by the condition in which a wealthy country allowed people to live in Jarrow in 1933, though it would appear that the greater part of the population at the time managed to remain either unaware of the reality of that condition or insufficiently moved by it, just as we mostly avert our gaze, deliberately or by self-protective habits of inattention, from the systematic waste of life that goes on around us in the present. Condition of England writing constantly reminds us that the nurturing soil of social injustice is inattention, ignorance and unconcern. The moralist calls on the reader to look and to focus. Ruskin had reminded the wealthy that they could enjoy their feasts only by averting their eyes from the starvation all around them, just as Orwell had drawn up a memorable list of comfortable pontificators whose peace of mind depended on refusing even to imagine the wretches who crawled underground to fetch coal for their fires. Priestley took his place in this tradition, and if his writing seems blowsy at times, that was perhaps a small price to pay for having a book containing such scorching pages at the top of the bestseller list. He may allow himself to do some stretches of the journey in his chauffeur-driven Daimler, but he writes as ‘the people’s’ champion when angrily repudiating the claims of well-off moralists that the fecklessness of the poor is the cause of their shoddy surroundings, and he is fiercely indignant at Tory claptrap about the unemployed living in luxury on the dole.

The England I looked at through the car window on the Birmingham ring road is vastly more prosperous, visibly more diverse, and at least somewhat more egalitarian in attitude than the England Priestley observed from the top of a tram in the same city. Yet reading English Journey, especially in the depths of another slump, it is easy to feel that less has changed than meets the travelling eye. Priestley can sound uncannily contemporary when expressing his bewilderment at the way whole communities have become the plaything of the global economy, or, for that matter, when he complains that money is ruining football. And he, too, has been told for years that various socially destructive things had to be done because ‘the City’ required them. ‘The City then, I thought, must accept the responsibility. Either it is bossing us about or it isn’t. If it is, then it must take the blame if there is any blame to be taken. And there seemed to me a great deal of blame to be taken.’

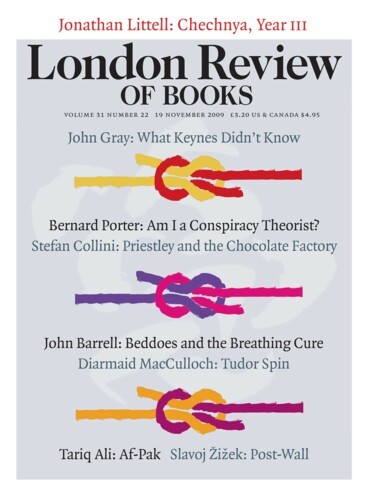

This new edition seems bizarrely misconceived. English Journey was not only a bestseller in the 1930s, but has been reissued several times in the past 75 years. The 1984 version was abbreviated (Swindon must have been thought too exciting for modern tastes), so this edition proudly claims to provide ‘the fully restored original 1934 text’, as though tireless scholars had unearthed some bibliographical jewel. Apart from a number of prefatory pages by current admirers of Priestley such as Beryl Bainbridge and Margaret Drabble, the chief novelty of this edition is that it has been printed in large coffee-table format to accommodate the numerous photographs that have been interspersed through the text. The addition of these photos, a curious mixture of unidentified ‘period’ images and recent shots, threatens to turn the book into something quite different, a patchy guidebook to the beauties of England. Thus, alongside the account of visiting Boston in Lincolnshire, we now have a photograph which is clearly not of Boston but which, to judge from details of dress and transport, comes from the interwar period. The caption, in its entirety, reads: ‘A typical English market scene. Rural and urban markets are still popular today. Most county towns still have a weekly market where farmers and traders sell their products.’ (There are several captions in this style, apparently written by a graduate of the Borat School of Tourism Studies.) In many cases, the connection to Priestley is negligible. Under a modern photograph of a thatcher on a cottage roof in Wiltshire we are told that ‘Priestley would perhaps have seen this man’s grandfather at work.’ A picture of the Selfridges building in Birmingham, completed in 2003, is described, inanely, as ‘far removed from anything Priestley would have come across in 1933’.

One begins to wonder whether the publishers are hoping the British Council might adopt English Journey as a handy introduction to the UK for the inquiring foreigner. For example, although the book mentions Sheffield only in passing, we are given a modern picture of a Sheffield mosque and told: ‘Most major towns and cities in England now feature Muslim places of worship’ (most of them feature lap-dancing clubs as well, but presumably these would be ‘off-message’). Most asinine of all is the placing in the last chapter of a fetching photo of the village of Finchingfield in Essex, ‘one of England’s prettiest and most photographed villages’. ‘Alas,’ the caption burbles, ‘Priestley travelled home in thick fog so would have missed this lovely spot.’ Have the editors and publishers actually read the book? Priestley makes quite clear that on leaving Norfolk he decides to curtail his travels and head straight back to London as fast as his chauffeur-driven Daimler will carry him. It was when coming down the A1 from Baldock into London that he encountered fog, which no more accounted for his having ‘missed’ Finchingfield (not mentioned in the text) than it did for his having missed, say, the Empire State Building, similarly hard to spot, even on the clearest day, from just north of Potters Bar.

This edition is part of a larger programme for the republication of Priestley’s major works. It is, of course, easy to be lofty about him, to see him as, at best, the poor man’s Arnold Bennett or, even less charitably, as Wilfred Pickles between hard covers. (In attempting to correct this, it is not necessary to go as far as one later admirer who wrote a book about him as the ‘last of the sages’.) One deterrent to taking too patronising a view is provided by his own sense of his public image, as expressed, for example, in a letter to his American publisher about the misleading way he is represented in American reviews of English Journey: ‘Here is Priestley, who became popular (undeservedly) by writing a lot of sentimental novels, watery imitations of Dickens; he’s a bovine hearty sort of ass; but about a third of the way through this book he suddenly discovers (and about time too) that all is not well with everything in this world.’ On this occasion, he was hoping that the publisher might be able to do something to make clear that his writings were ‘serious pieces of work and not sentimental catch-penny tushery’.

Perhaps the case needs to be made again. In his preface to this new edition, Roy Hattersley, a predictable admirer, calls the book ‘a masterpiece’, which it isn’t: when he describes it as ‘a social commentary, a polemic and a love story’, he is nearer the mark, and the way in which those aspects of the book are interwoven is part of what makes it more than journalistic opportunism. There is a good deal of sentimentality in English Journey, and a certain amount of cheap writing. But it is, in its fashion, a serious and even moving book about the tensions between ‘the way people want to live’ and the way they ought to want to live, and 75 years later we can’t complacently conclude that we have made much progress in resolving these tensions.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.