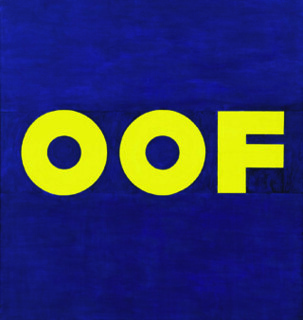

‘Whatever my work was made up of in the beginning,’ Ed Ruscha said in 1989, ‘is exactly what it is like today.’* Well, not ‘exactly’, but his art is consistent, and this is still true 20 years later, as is made clear by the excellent survey of his paintings of the last 50 years curated by Ralph Rugoff, now at the Hayward until 10 January. Ruscha is ever intrigued by ‘paradox and absurdity’, and for all the immediacy of his images, which combine the emphatic qualities of both abstract art and commercial design, they also emit a low or high buzz of ‘visual noise’, a little or large glitch in communication that provokes ‘a kind of a “Huh?”’ in the viewer. Most often Ruscha produces this ‘Huh?’ effect through mischief with the relationship between words and pictures. On the one hand, he treats words as images in their own right; on the other, reading is never quite congruent with seeing in his work. ‘A flip-flop between those two things’ is how Ruscha describes the relationship, though a weird elasticity is even closer to the case: ‘I like the idea of a word becoming a picture, almost leaving its body, then coming back and becoming a word again.’ The upshot of these visual-verbal miscues is a sequence of puzzles that look obvious but are impossible to solve.

His great interest in the ‘Huh?’ effect, Ruscha tells us, stems from his ‘deep respect for things that are odd, for things which cannot be explained’. This admiration for the odd thing, moreover, is bound up with an appreciation for the common thing – for vernacular words, images and objects that, however familiar, are made strange when held up for examination. Early on, for instance, Ruscha painted some motifs actual size, which is how they are often painted in folk art: that is, in a manner that appears at once common and odd. In Actual Size (1962), a can of Spam, depicted at scale, seems to fly, replete with fiery after-burner, through the space below, while the word ‘Spam’ appears in yellow capitals on dark blue in the space above. A common joke of the time – early astronauts were called ‘spam in a can’ – thus issues in an odd painting, in large part because, as Ruscha remarks, words ‘exist in a world of no-size,’ and so his juxtaposition of the ‘actual size’ of the can and the ‘no-size’ of the word renders the pictorial space of Actual Size very uncertain.

Ruscha draws out the common from folk and Pop elements alike. Biographically he is well positioned to do so: born and raised in the Midwest, often seen as the folk heart of the US, Ruscha migrated to Los Angeles, often taken to be its Pop capital, and he is fully aware of the ‘Okie’ tradition in this passage. ‘In the early 1950s,’ he once remarked, ‘I was awakened by the photographs of Walker Evans and the movies of John Ford, especially Grapes of Wrath, where the poor “Okies” (mostly farmers whose land dried up) go to California with mattresses on their cars rather than stay in Oklahoma and starve.’ Even as Ruscha presents this folk experience as already mediated, he is not willing to let go of the folk per se: for example, some of his early paintings allude to naive signage, another attribute of folk art, and his bird and fish paintings of the mid-1960s also play on folk painting, in this case of amateur naturalists and outdoorsmen. There is a common element in kitsch, too, which Ruscha also prizes.

This concern with the common first led Ruscha to Marcel Duchamp and Jasper Johns. Duchamp ‘discovered common objects’ as artistic material, Ruscha once claimed, and, like Johns, Ruscha has made them ‘the foreground central subject’ of his work. He first did so at a time when increased commodification altered the look not only of common objects but also of common words, images, colours, spaces – in short, the nature of appearance. In effect, he updated the Duchampian readymade in a way that addresses this condition, and again his aim was not only to trouble our automatic perception of these things but to wrest a common element from them. For every impulse in his work to mock, even to destroy, ‘standards’ and ‘norms’ (his famous representations of the Standard gas station, Norm’s diner in LA and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, all in flames, appear in this exhibition), there is a counter-impulse to reclaim the degraded commonplace as a shared vernacular. Centrally, too, the found language of his jokes, sayings and clichés (one early painting here reads simply ‘Boss’, another ‘War Surplus’) is shared: as no one possesses this kind of speech, everyone can partake of it.

Ruscha might be consistent, but the weather of his work changes in the mid-1980s. Where once his words were liquid-hot and his skies toxically brilliant, both take on a foggy chill, and almost everything becomes nocturnal. With new motifs, like old clock faces and black and white film frames, the sense of time shifts, too, as if his subjects had receded not only into the dark but into the past. In large part this effect is due to his dominant technique of the last two decades, the silhouette, which he associates with ‘things that are immediately recognisable’, like icons and logos. Yet even as his silhouettes suggest a powerful collective symbol, a shared memory image, they also intimate the fading-away of these trusted things. The darkening in this period seems cultural, too, as though, not long after Ronald Reagan declared it ‘morning again in America’, Ruscha had countered with an evening world: in the paintings of this period we sense not ‘a shining city on a hill’ but the twilight of American gods.

The exceptionalism of the United States – its democratic dream, its eternal future – was long staked on its Western frontier, but in a cycle of paintings from the mid-1990s Ruscha displays such things as silhouetted teepees, buffalos and wagon trains headed for the dark, with the implication, already at work in some Westerns, that the West is largely a myth and that it is bound to end soon anyway. And this fading-to-black is not limited to Western subjects: such American symbols as a smalltown church and a row of suburban houses are also presented in this ghostly way. Meanwhile the evocation of the common shades into an intimation of the solitary. In one especially powerful painting at the Hayward, a lone coyote howls in the night, its figure as shadowy as any moon. In Native American lore the coyote is a ‘trickster’: an in-between creature, at home everywhere and nowhere. This is the mood of many of the recent paintings. Another image shows a ghost ship under full sail in a way that calls up the great Kafka story of the Hunter Gracchus, who, neither dead nor alive, is doomed to wander from port to port: ‘Nobody knows of me, and if anyone knew he would not know where I could be found, and if he knew where I could be found he would not know how to deal with me, he would not know how to help me.’ The spiritual America that Ruscha has limned over the last 50 years stretches from that hopeful Okie headed west on Route 66 to a contemporary version of the lost Gracchus.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.