Sports administration is one of those jobs which have built into them the fact that they attract attention only when things go wrong. A school sports day takes quite a bit of organising; anything bigger, and the complications grow exponentially. Events such as Wimbledon or the World Cup are mechanisms of extraordinary complexity, in which most of the moving parts are human, and these events are, in their way, heroic feats of administration and bureaucracy and man-management – and all that effort just goes to set the stage for the real action. The whole point of all this work is to go unnoticed. Being a sports administrator is a bit like being a spy, in that attracting attention is by definition a sign that something has gone amiss.

The case of Caster Semenya has seen the administration of athletics go about as badly wrong as it possibly can. Semenya is the 18-year-old South African woman who won the 800 metres World Championships in Berlin this August, having improved her personal best by startling margins: in the final of the 800 metres African Junior Championship a few weeks previously, she did so by four seconds. The body which administers athletics, the International Association of Athletics Federations or IAAF, responded by making Semenya take a gender test, a fact which was immediately and unforgivably leaked to the world’s press, causing planet-wide interest, speculation and scandal. Another wave of scandal hit when the specific test results were leaked: they allegedly showed that Semenya had both male and female sexual characteristics, and an unusually high level of testosterone. The news caused justified outrage in South Africa, where the sports minister, Makhenkesi Stofile, said that if the IAAF were to ban Semenya, ‘it would be the third world war’. It then emerged that Athletics South Africa had performed gender tests on Semenya before she competed in Berlin.

Hard cases make bad law. Gender tests were briefly a routine feature of international athletics, but now they are only ordered in specific instances, because they are both complicated to do – involving endocrinology, gynaecology and internal medicine – and complicated in their philosophical consequences. There was a happily naive period in the late 1960s and 1970s when it seemed as if gender testing was a straightforward issue involving Soviet bloc athletes who were either men pretending to be women, or women whose coaches had made them take so many illegal hormones that they were turning into men. Example: a pair of Soviet sisters, Irina and Tamara Press, set 26 world records in the early 1960s, but didn’t show up for sex testing when it was first introduced in 1966, and were never seen again. Photos of large, impossibly muscular and hairy Soviet bloc athletes were a routine feature of the sports pages. The high spot/low spot of this historical moment came at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, when every single female athlete except Princess Anne was subjected to a sex test which involved nothing more complicated than a grope. If the test was too demeaning for Princess Anne, it should have been too demeaning, full stop – though in the face of the great Soviet hairy women offensive, that’s not how the International Olympic Committee chose to see it.

Subsequent years saw the process of gender testing become more sophisticated. This was the point at which things became truly complicated, because the tests showed an unexpectedly large number of female athletes had naturally high levels of male hormones and quite a few had the male Y chromosome. The athletes in question had no idea, and the effect of ‘failing’ a sex test in this way was often highly traumatic. Furthermore, it was always and only female athletes who went through this experience; there hasn’t been a single instance of a male athlete turning out to be partly female. (As many men have inter-gender characteristics as do women; but it’s the male hormones, especially testosterone, which are useful in sport.) As a result, the IAAF stopped performing compulsory sex tests in 1992, and the IOC, the body that runs the Olympics, followed their example in 1999. The fact that the question of blurred gender distinctions is, in the athletics world, so well known, makes the IAAF’s failure in the instance of Caster Semenya all the more culpable.

In the ordinary run of things, women’s sex chromosomes are XX and men’s are XY. (When Ted Heath rang up the editor of the Dictionary of National Biography to complain about the way something he’d written had been copy-edited, he was put through to the editor, Dr C.S. Nicholls. When she answered, Heath found himself for a moment speechless with surprise. He finally managed to blurt: ‘Why are you a woman?’ Her reply: ‘Because I have two X chromosomes.’) It is not, however, the chromosomes which directly control gender; the determining factor is the hormones which the chromosomes, taken together, instruct the body to make. In some cases, there is a discrepancy between the chromosomes and the body’s hormone kit; in particular, some women are chromosomally XY, but also produce a hormone which blocks the operation of the male hormones. They are women, but with a Y chromosome. Women affected with this condition are tall and lean and often very striking looking. They have a vagina but no uterus, and often have testicles which don’t descend and which are, in the developed world, removed to reduce the risk of cancer. Many of these women become actresses and models.

I must admit, I’d always thought that tales of celebrity hermaphroditism were wishful thinking, a bit like stories about famous actors with mice stuck up their backsides owing to S&M experiments gone wrong – but once you hear the science, you do start to wonder. Two historical figures I’ve heard mentioned in this context are Wallis Simpson and Marlene Dietrich. The condition (the XY one, not the dead mouse one) is rare, but not that rare: one case in 15,000. That means that there are four thousand of these women in the UK alone. Globally there are 400,000. Since encountering this fact, I find I look at fashion photography in which the women don’t look like anyone you’ve ever seen in real life in a new light. A speaker at the Lib Dem conference raised the issue of making magazines carry a sticker admitting when photographs have been digitally manipulated, to prevent young women being oppressed by an unachievable idea of physical perfection. But what about the idea that the physical ideal they are sometimes being invited to admire is chromosomally XY? And that’s just the specific case of this particular condition, which is Swywer syndrome, or XY gonadal dysgenesis. More general conditions involving gender abnormality affect one in three thousand people – which, globally, is two million people. There are more human beings who are in some degree intersex than there are Botswanans. I’m not sure what conclusion one should reach, other than that the lives of people with intersex conditions might be easier if this fact were more widely known, and that Ms Semenya has been very harshly handled.

Send Letters To:

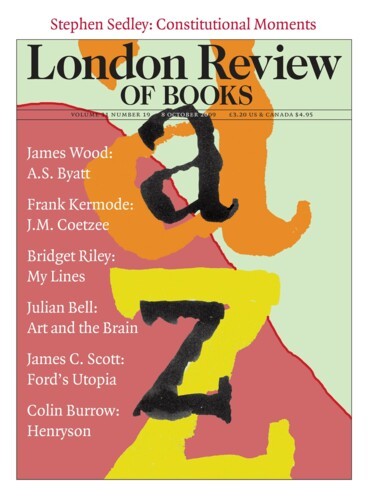

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.