Richard Hamilton’s ‘Protest Pictures’ have turned the galleries of Inverleith House in Edinburgh into a time-machine.* News events from the last fifty years flash up in every room, from a drug bust and a student murder in the 1960s, through the Troubles in the 1970s and 1980s, to the Gulf debacles of the last two decades. In each instance Hamilton is concerned to capture the mediation of the event in order both to deconstruct its effects and to turn them to his own ends.

The first stop is a scandal in Swinging London. In February 1967 police arrested Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser (a prominent art dealer) for drug possession. Based on a press photograph of Jagger and Fraser in a police van, Swingeing London 67 (1968-69) is blurred, its colours lurid. The two celebrities, who otherwise thrive on our gaze, here attempt to deflect it, lifting their hands, which are manacled together, to hide their faces; at the same time the handcuffs double as bracelets displayed for the public. The painting is about swingeing justice as well as swinging stars, but it also anticipates a media regime in which transgression promotes adoration, manacles are forged into bling, and sheer visibility trumps all.

The next image is from 1970. Hamilton set up a camera in front of his television for a week in May. The events at Kent State University – the shooting of student protesters by Ohio National Guardsmen – were in the news that week, and he made several exposures, choosing one showing a blurry shape. Cued by the title, Kent State, we soon identify the figure as a fallen student; he lies inert on the ground, legs truncated, tended by two figures that are even more partial and obscure. The televisual frame of the image is registered in its scan lines and its curved border surrounded by black; the printing process, involving 13 layers of transparent colours, further distances the picture. At the same time this layering lends a haunting spectrality to the familiar blur of the televisual image, and it allows red splotches suggestive of blood to cut the anaesthetic blues of the image. As remediated here, the picture is both hot and cool, piercing and deadening.

At this point Hamilton was already feeling his Pop enthusiasms fade; by the time Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979 they seemed frivolous. Treatment Room (1983-84) is an installation that evokes a bare clinic: a partition with a window, a white trolley partially covered by a standard blanket, and an intrusive monitor showing a looped video of Thatcher delivering her final speech before the 1983 general election. In effect, the notional patient undergoes two kinds of treatment at once, institutional control and political propaganda. In the Thatcherism X-rayed in Treatment Room, there might be ‘no such thing as society’, but there is certainly a state, and here its apparatuses have become a subject of history in their own right.

During the making of Treatment Room, Hamilton was already at work on a painting focused on another disciplinary institution, prison. The citizen (1982-83) became the first of three major canvases concerning the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Each work is a grand diptych whose format and scale summon the traditions of the altarpiece and history painting respectively. In The citizen a young man, shaggy and bearded, stands on a bare mattress; only a blanket cloaks his body; a sheet is wrapped around his waist. His space is very confined, there is rumpled bedding and scattered debris at his feet, and the walls are covered with brown swirls. The citizen, we soon perceive, is an IRA prisoner, and the space is his messy cell; the source is again a television image, from a BBC documentary about the Maze. The citizen appears here in the midst of a ‘dirty protest’, his excrement smeared on the walls. On the one hand, he is without a state to call his own, and this condition makes him a rebuke to the authorities. On the other hand, the scene of subjection is also a theatre of promotion, a powerful public-relations image. Like many of the ‘Protest Pictures’, The citizen embodies contradictory values and elicits ambivalent responses.

The protagonist of The citizen refuses the status of subject to the crown; the protagonist of The subject, the second painting in the Troubles trilogy, embraces it. He is an elderly member of the Orange Order on a Loyalist march in Belfast, and Hamilton presents him in full regalia: black suit, bowler hat, orange sash and insignia, huge white cuffs and kid gloves, erect sword. Beside him is a murky night-time scene of armoured vehicles on patrol in a Belfast street littered with bomb debris. As pictured by Hamilton, the citizen and the subject are opposites, to be sure, but also doubles, and this complicates everything: both attest to a desperate, rancorous pride, and both claim a territory that they mess up – a cell painted with shit, a street sculpted with rubble.

Sympathies are more mixed in the final work in the Troubles cycle, The state (1993). Here again the figure – a young British Army paratrooper on patrol in Belfast, with camouflage fatigues, visored helmet, and rifle at the ready – is composed of several pictures, mostly news images. Like the subject, he has a weapon and a uniform – and his are not merely ceremonial. But at the same time, like the citizen, the young man seems caught in a space that he is ordered to control.

At Inverleith House the three paintings form a triptych, with The citizen in the centre (he alone gazes at us) flanked by The state to the left and The subject to the right. The citizen is hemmed in by his doubles, but somehow served by them as well. The three are antagonists, rivals and relatives all at once, and the trilogy triangulates them in such a way that their visual relay conveys their historical entanglement.

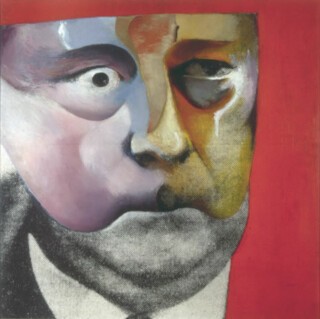

‘Protest Pictures’ concludes with two portraits of flawed Labour leaders, Hugh Gaitksell and Tony Blair, separated by four decades. When Gaitskell led Labour in the early 1960s, he defied its rank and file with a Cold War policy of nuclear deterrence. Hamilton, who was committed to the anti-nuclear movement, made his Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland in 1964. Once a progressive figure, Gaitskell appears here misshapen by his own misdeeds, part Phantom of the Opera, part cadaver, a monstrous omen of nuclear horrors to come. Blair, in Shock and Awe (2008), appears in a Roy Rogers shirt, jeans and cowboy boots, with six-shooters and straps that are too big for his short legs. The dioramic space behind him, a fiery purgatory, evokes Baghdad on the first night of ‘Shock and Awe’, but the shock and awe is Blair’s too: they are registered in his eyes and in the lines of his face. Once again the artist’s pictorial pastiche rehearses and exposes the political pastiche performed by his subject.

‘Pop history painting’ seems almost an oxymoron. There are a few exceptions: Warhol’s ‘Race Riot’ silkscreens, for example, or Gerhard Richter’s Baader-Meinhof canvases. The powerful iconicity of Hamilton’s ‘Protest Pictures’ places them in that company. An old Pop associate, Eduardo Paolozzi, labelled his early collages ‘bunk’. If history is bunk, as Henry Ford declared, then a critical form of Pop remains an excellent way to debunk it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.