The prodigiously gifted artist and writer Joe Brainard died of Aids in a hospital in New York in May 1994, at the age of 52. He had long been revered in certain parts of the New York art and poetry worlds, though he never achieved, or, by all accounts, desired, the celebrity and status of Andy Warhol or Claes Oldenburg or Jim Dine, alongside whose work his elegant collages were first presented to British gallery-goers at the Hayward’s Pop Art show of 1969. But Brainard wasn’t really a Pop artist, and though a big Warhol fan, instinctively resisted the brutal equation between art and commodification that Pop Art propounded. In an interview of 1977, around the time he more or less gave up his artistic career to devote himself to his two favourite recreations, smoking and reading novels, Brainard suggested it was probably the eclectic nature of his output that had saved him from developing into a brand name:

I don’t have a definite commodity … I’ve had oil-painting shows that were very realistic, then I’ve done jack-off collages, cut-outs one year and drawings … it’s all been different … People want to buy a Warhol or a person instead of a work. My work’s never become ‘a Brainard’.

Or even a Jainard or a Bernard or a Joe. Here are the last six ‘I remember’s from his sparklingly original and ‘totally great’ (to use one of his own favourite locutions) memoir, I Remember, issued in four instalments between 1970 and 1973, and then collected in a single edition in 1975:

I remember one day in psychology class the teacher asked everyone who had regular bowel movements to raise their hand. I don’t remember if I had regular bowel movements or not but I do remember that I raised my hand.

I remember changing my name to Bo Jainard for about one week.

I remember not being able to pronounce ‘mirror’.

I remember wanting to change my name to Jacques Bernard.

I remember when I used to sign my paintings ‘By Joe’.

I remember a dream of meeting a man made out of a very soft yellow cheese and when I went to shake his hand I just pulled his whole arm off.

Brainard was born in 1942 and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he won almost every art prize going. A precocious draftsman, he initially intended to become a fashion designer, and was hailed at 14 by a Tulsa newspaper as a ‘budding Dior’. I Remember suggests he was interested not only in designing women’s clothes, but in wearing them too:

I remember when I went to a ‘come as your favourite person’ party as Marilyn Monroe …

I remember that for my fifth birthday all I wanted was an off-one-shoulder black satin evening gown. I got it. And I wore it to my birthday party.

In 1959 he was approached by a couple of fellow students at Tulsa Central High to be the art director of a magazine they were starting; though it ran for only five issues, White Dove Review succeeded in attracting contributions from a number of the leaders of the country’s emerging counter-culture, including Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, LeRoi Jones and Robert Creeley. It also ran a selection of the early work of a maverick graduate student in English at the University of Tulsa, Ted Berrigan. Berrigan was soon accompanying Brainard and his fellow editors, the poets Ron Padgett and Dick Gallup, on their forays into Tulsan bohemia, and together they began experimenting with the artistic possibilities unleashed by speed pills such as Benzedrine. Almost overnight, as Padgett records in his illuminating biography, Joe (2004), Brainard’s ambitions shifted from fashion design to avant-garde art. Over the next few years each of the Tulsa Four migrated to New York, where for a while Berrigan and Brainard shared a store-front room on East Sixth Street, one sleeping on the single bed by day, the other by night. They survived by shoplifting and selling their blood for $5 a pint. Things weren’t always easy between them: ‘I remember painting “I HATE TED BERRIGAN” in big black letters all over my white wall.’

The downtown New York art and poetry worlds enjoyed an almost symbiotic relationship in the early 1960s, and their appeal to Brainard and the other Dust Bowl refugees (as Padgett once called them) is often vividly captured in I Remember:

I remember the first time I met Frank O’Hara. He was walking down Second Avenue. It was a cool early spring evening but he was wearing only a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up to his elbows. And blue jeans. And moccasins. I remember that he seemed very sissy to me. Very theatrical. Decadent. I remember that I liked him instantly.

He even went to the trouble, he tells us, of learning to play bridge in order to get invited to O’Hara’s bridge evenings, which proved to be ‘mostly talk’; it fell not to O’Hara but to his roommate Joe LeSueur (who records the evening in some detail in Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara) to initiate the gawky, shy, stuttering new arrival into the city’s gay scene. ‘I had the feeling,’ LeSueur rejoiced, ‘he had waited all of his 21 years for what we conspired together.’

The New York School poets’ conflation of high and popular culture served as a catalyst for Brainard’s art; his early collage pieces combine all kinds of artefacts, but he was particularly drawn to the devotional objects he found in local Puerto Rican bodegas and Ukrainian religious shops. His first one-man show in 1965 was a tour de force of street and junk-store scavenging, a series of assemblages that made loving use of cigarette butts, lobster claws, a rubber fried egg, Madonnas, an American Indian’s head, 7-Up bottle caps, ostrich feathers, a moose statuette, pink rubber snakes, crucifixes, purple plastic grapes. Almost a year spent in such poverty that he took up panhandling seems to have enabled Brainard to see that anything could find its place in his rigorously constructed but ecumenical bric-à-brac shrines. One from 1965 named Prell after its central component, a very green shampoo, was well described by James Schuyler:

A dozen bottles of Prell – that insidious green – terrible green roses and grapes, glass dangles like emeralds, long strings of green glass beads, a couple of strands looped up. Under glass, in the centre, a blue-green pietà, sweating an acid yellow. The whole thing cascades from an upraised hand at the top: drops and stops like an express elevator. It is a cultivated essence of shop-window shrines and Pentecostal chapels (John Wesley with tambourines, lugubrious and off-pitch). Its own particular harsh pure green is raised and reinforced until it becomes an architecture. It is to green what a snowball is to white, an impactment.

Although Brainard was raised a Methodist, these eccentric and uncanny altarpieces are neither in favour of nor against religion. In a letter to Schuyler in 1963 he allowed that one of his intentions was to ‘purify objects’, but that purification was to be achieved by wholly aesthetic means. There is no irony in Brainard’s juxtapositions, but a fascination with form and texture and colour, with things as they are, and with the patterns they can be made to form when judiciously placed in relation to each other.

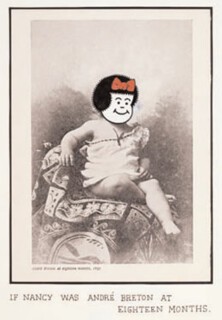

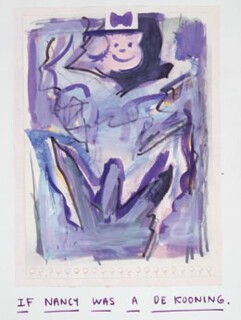

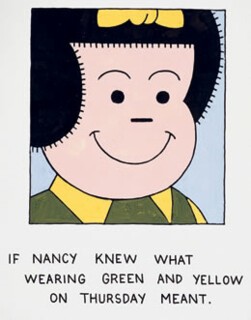

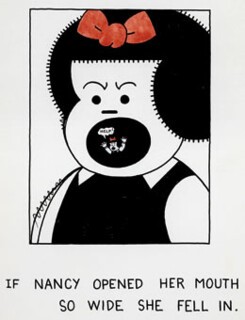

The collaborative work of poets such as O’Hara and Schuyler and Ashbery and Kenneth Koch also had an inspirational effect on Brainard. He adored working with others, particularly on spoof comic strips featuring characters like the tough cowboy Red Ryder (the source of a hilarious mini-narrative with words by O’Hara) or Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, who, with her frizzy halo of hair, adorned just above the forehead with a bright red bow, her rounded body, stocky legs, and her sidekick called Sluggo, had developed since her first appearance in 1933 into what Edmund White has called ‘an unchanging icon of the American norm’. Nancy first figured in Brainard’s work in 1963, in collaborations with Padgett and Berrigan, and thereafter found herself making more than a hundred surprise guest appearances, often in the most unlikely of circumstances: ‘If Nancy Was a Building in New York City’ (that famous skyline with her spiky corona of hair replacing a block in midtown); ‘If Nancy Was a Sailor’s Basket’ (a diminutive Nancy waving from the front pouch of one of the US Navy’s finest); ‘If Nancy Was President Roosevelt’ (a grinning Nancy replacing Teddy Roosevelt between Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln on Mount Rushmore); ‘If Nancy Was a Drawing by Leonardo da Vinci’ (her stolid features and purposeful stomp sketched on a sheet of Old Master drawings between noble profiles, sorrowing Madonnas, plaintive putti and snarling lions); ‘If Nancy Was the Bright’s Disease’ (an alarmed Nancy grimacing inside a diseased kidney taken from a medical journal); ‘If Nancy Was André Breton at 18 Months’ (her head imposed on a photograph of the future Pope of Surrealism in his divine infancy). As intrepid as Bushmiller’s original, there is no aesthetic terrain Brainard’s all-conquering heroine hesitates to invade. For the cover of the Art News Annual for 1968 Brainard Nancified 16 classic paintings that range from the Mona Lisa to Warhol’s soup cans, from Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson to a Jasper Johns target (an ebullient Nancy waving at its centre, and fragments of her features appearing in the grille above), from Goya’s La Maja Desnuda to a Nancy drowning in Pollock drips and yelling out: ‘The Avant-Garde’.

Ron Padgett, in his foreword to this delightful collection of Brainard’s Nancy oeuvre, says it’s unlikely that Brainard had heard ‘Nancy’ or ‘Nancy-boy’ used as terms of homophobic abuse during his adolescence in Tulsa. Nancy is, however, featured in one picture sporting bright green and yellow instead of her standard outfit of black and red (with the caption: ‘If Nancy Knew What Wearing Green and Yellow on Thursday Meant’). This connects it with an entry from I Remember: ‘I remember when, in high school, if you wore green and yellow on Thursday it meant that you were queer.’ We also get Nancy as a sexy blonde in furs, as the star of a blue movie responding delightedly to the attentions of two hunks, and in an X-rated strip made with Bill Berkson in 1971 enjoying congress with another comic character called Henry (created by Carl Anderson in 1932) in a pretty comprehensive range of sexual positions.

As in his pseudo-Christian assemblages, his many collages which make liberal use of male pornography and the more explicit bits of I Remember, Brainard manages to fuse the innocent and the transgressive so thoroughly it’s impossible to disentangle them. In her introduction to The Nancy Book the poet Ann Lauterbach notes that the birth of Brainard’s Nancy was more or less contemporary with Susan Sontag’s ‘Notes on “Camp”’ (1964), which set out to define the different kinds of humour that get lumped under this term. Sontag’s major distinction was between naive and deliberate camp, but it seems to me that Brainard’s art and writings manage somehow to straddle this fault line: they refuse to be knowing or conspiratorial, yet one is repeatedly dazzled by their aesthetic surefootedness and precision. Many of Sontag’s observations, however, do seem to reflect the freedom and joie de vivre of Brainard’s work: ‘Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralises moral indignation, sponsors playfulness … Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of “character” … Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying … Camp is a tender feeling’ – and one not to be confused with the ‘ultimately nihilistic’ attitude she sees embodied in Pop Art. Sontag also notes that camp taste depends – or at least it did back then, when the notion of a Graham Norton fronting prime-time television shows was unimaginable – on being shared, and constantly refined and embellished, by a coterie of the like-minded. Brainard’s art was insistently social; it served partly as a means of responding to and pleasing his literary friends (to whom he frequently gave it), but often also as a way of promoting their work. Brainard ended up designing book covers and poetry flyers for a fair percentage of first and second generation New York poets, who also feature on a regular basis in the journal extracts reprinted in books such as Selected Writings (1971), New Work (1973) and the enchanting Bolinas Journal (1971), which includes line drawings of Berkson, Berrigan and Creeley.

Nancy, Lauterbach plausibly suggests, served as an alter ego or transitional object for Brainard: ‘Through her, what is exceptional about him, specifically but not only his gayness, is rendered common, ordinary.’ While on one level she is a talisman of his Tulsan childhood, Nancy’s dramatic reconfiguration as, say, a painting by de Kooning or a drawing by Larry Rivers, charted Brainard’s own quest to become a part of the avant-garde scene in a city that had fairly recently developed into the international capital of the arts. Nancy, as Lauterbach puts it,

could travel with Joe from his humble roots in Tulsa to the bright complexity of New York City; she could be his virtual companion and sidekick as he negotiated the sophisticated, charged world of such figures as Warhol and O’Hara. Nancy could be inserted into this world, instantly stripping it of its formidable aura, transforming it into an accessible, intimate realm.

Her pluckiness and determination shine through her beady eyes (except when they turn into psychedelic circles in ‘If Nancy Was an Acid Freak’) and stiffen her implacably fixed grin. But Brainard also sometimes used her as a comic means of expressing states of anguish and uncertainty: in ‘If Nancy Opened Her Mouth So Wide She Fell In’ a tiny Nancy shouts for help from inside the yelling maw of a big one, while in ‘Some Studies for Fear’ several roughly sketched Nancys flee and scream and panic, the black Os of their mouths looking like bottomless voids of anxiety and distress. Great droplets of sweat arc from the helmets of their hair. In ‘Fear’ itself a single leaping Nancy confronts some nameless terror from which there seems no escape, not even through art, which may even be part of the problem, for Brainard has painted a frame around the image, and its title, his name and its date of composition (1972) are inscribed on a placard beneath. One of the fears it dramatises is that of being trapped in art itself.

Between his arrival in New York in 1961 and his last one-man show there in 1975, Brainard produced thousands of works. The last show alone contained 1500 pieces (whittled down from 3000), for Brainard had decided to ‘Think Tiny’, as the headline of People magazine’s review of the exhibition put it. The show consisted of rows and rows of miniatures, a kind of vast cabinet of small everyday curiosities and wacky mini-assemblages fashioned out of stamps and logos and bits of string and luggage labels and books of matches and playing cards and whatever else happened to catch Brainard’s magpie attention. The effect must have been something of a visual analogue to the thousand-plus discrete, seemingly random entries that make up the complete I Remember, also published that year:

I remember ‘Korea’.

I remember giant blackheads on little faces in tiny ads in the back of magazines.

I remember fancy yo-yos studded with rhinestones.

I remember once when it was raining on one side of our fence but not on the other.

I remember rainbows that didn’t live up to my expectations.

I remember big puzzles on card tables that never got finished.

I remember Oreo chocolate cookies and a big glass of milk.

For all the specificity of the details, such a list is as available and generic as a comic character like Nancy. Once popularised by Koch in his primers for teaching poetry to children, the ‘I remember’ format quickly became a staple of school – and adult – creative writing classes. What could be simpler?

I remember my first sexual experience in a subway. Some guy (I was afraid to look at him) got a hard-on and was rubbing it back and forth against my arm. I got very excited and when my stop came I hurried out and home where I tried to do an oil painting using my dick as a brush.

Obviously the textbooks omit that one. Harry Mathews, a friend of Brainard’s, explained the concept to his fellow Oulipian Georges Perec, who composed his own Je me souviens (dedicated to Brainard), which was published in 1978, and the genre took off in France too. When Perec died five years later Mathews commemorated him with a text entitled ‘The Orchard’ made up of 123 ‘I remember’s. What other format could have preserved for posterity details such as the following? ‘I remember Georges Perec expressing his appreciation of the towelling called Essuitout: “Ça essuie vraiment tout!”’

When asked about his prolificness in interviews Brainard freely acknowledged that it was partly the result of the large quantities of speed he took. During the early 1970s he’d work for days without stopping, sifting through the thematically coded piles of bric-à-brac in his loft on Greene Street, or snipping paper with X-acto blades to fill plexiglass boxes with imitation foliage. His great goal, though, was to master oil painting, and it was partly his failure, in his own eyes, to do so, that led to his ‘easing off’, in Padgett’s phrase, to his willingness to spend his days immersed in the fiction of Barbara Pym rather than taking the Manhattan art world by storm. He experienced a ‘speed-crisis’ around 1976, one he’d anticipated some years earlier: ‘A mad fiend, yes,’ he wrote of the pills that kept him humming, ‘but I’m willing to pay. The time will come.’ In Joe, Padgett graphically describes the manic Brainard of the early and mid-1970s, and the lassitude that seized him once he finally kicked his amphetamine habit, and began catching up on lost sleep. ‘People who don’t work,’ he mused in his 1977 interview, ‘I don’t know how they fill up the day. You can read, I guess … ’ An extract from a letter written to Padgett in the summer of 1984 captures the flavour of his aimless but not unhappy late years of unproductivity: ‘Rereading some old reliables, like Madame Bovary and Great Expectations and several Barbara Pyms. Play at work from time to time, but …’

Brainard’s favourite flower was the pansy – another double entendre – and pansies feature prominently in his many gorgeous ‘all-over’ flower pictures, which he created by painting individual blossoms, cutting them out, and then gluing them to the canvas. Again, these dazzling fields of evenly spread blooms are neatly poised between artistic polarities, evoking both the macho action painting of the abstract expressionists and the less exalted, more domestic traditions of wallpaper, appliqué and quilting. A further riff on the ‘all-over’ canvas comes in his pictures of male torsos covered in tattoos of hearts and butterflies and birds and snakes and the names of his friends. Like most New York-based artists of his generation, Brainard lived in the long shadows cast by the heroic, mythical breakthroughs of Pollock and de Kooning. (Even Warhol felt obliged to pay a very characteristic homage to Jack the Dripper, by peeing, and getting his friends to pee, on large specially prepared canvases, thus creating a series of Pop Art versions of the drip painting.)

Brainard’s love affair with oils was partly inspired by a desire to emulate de Kooning, but his work in the medium was insistently realist: a beautifully observed rack of toothbrushes, a white dog asleep on a green sofa, or, in one called Whippoorwill’s World, the same dog reclining on the front lawn of a house (that of Brainard’s partner Kenward Elmslie in Calais, Vermont) in a mock allusion to Andrew Wyeth’s poster-friendly Christina’s World. Brilliant as these are, the process of oil painting appears to have made Brainard aware that he lacked a certain self-belief, or egotism, a quality which painters determined at all costs to be great seemed to him to share. He feared he hadn’t sufficient ‘patience’, as he put it in a letter to Fairfield Porter of 1972, to do justice to the ‘authority oils carry for me’.

It is, though, precisely the absence of ‘authority’ that makes Brainard’s work so charming and available, so true a response to the variegations of the everyday; it never badgers us to admire it, or promises some life-changing revelation. It asks to be appreciated not as a concept, as a ‘Brainard’, but as a compilation of a myriad small perceptions and memories. It is hard to think of an artist both so original and so unconceited. ‘Sometimes/everything/seems/so/ oh, I don’t know’ he observes in one of his witty little poems. If his work repeatedly throws us off balance, it is with delight, as when one notices in a picture of a wholesome, blue-eyed baby a minute and grinning Nancy in the left eye.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.