The term ‘graphic novel’ is dismissed by most of its practitioners as either an empty euphemism or a marketing ploy. As Marjane Satrapi puts it, graphic novels simply enable ‘the bourgeois to read comics without feeling bad’; according to Alan Moore, they allow publishers to ‘stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel’. Moore and Satrapi, in common with many others, want their work to be known as ‘comics’. But ‘graphic novel’ can usefully designate a certain type of comic: a single-author, book-length work, meant for a grown-up reader, with a memoiristic or novelistic narrative, usually devoid of superheroes. By contrast, the older and more capacious term ‘comic book’ recalls the thinner, serialised, multi-authored or ghost-written publications rife with Supermen and She-Hulks. Some comics, of course, straddle (or elude) both categories; but in broad terms ‘comic book’ and ‘graphic novel’ serve to distinguish two trends in the history and form of comics.

There is no better vantage-point from which to view these two trends than the new collection of Will Eisner’s autobiographical comics, entitled Life, in Pictures. Eisner’s career is a microcosm of the history of American comics, starting with the ‘golden age’ of the 1930s and 1940s. When he was 19, Eisner co-founded one of the first comics studios, Eisner & Iger, whose original titles included Sheena, Queen of the Jungle and Blackhawk, as well as the underappreciated Mr Mystic and Doll Man. Mr Mystic – his real name was Ken – crashed a plane in Tibet, where the ‘Seven Lamas’ tattooed an arcane symbol onto his forehead, endowing him with the ability to transform into animals. Then there is Darrell Dane, a research chemist with the ability to ‘compress his molecular structure’ until he has shrunk to a height of six inches; the Doll Man’s crime-fighting techniques involve hiding in handbags, bivouacking in pie dishes and riding a German shepherd dog. In 1940, Eisner created his most famous masked hero: The Spirit was a syndicated series featuring a former detective called Denny Colt who staged his own death and took up residence in a graveyard, whence he made periodic forays into the world of crime.

The virtuosity of The Spirit is such as to belie the idea of a comic ‘strip’. The panels, as if themselves infused by an exuberant ‘Spirit’, leap from their rectangular boxes, assuming the forms of diverse print media: file cards, gravestones, film strips, children’s books, television sets. Eisner’s panels often float against black Expressionist nights or lightly inked Center City skylines. Some scenes are framed by purely visual devices: the beam of a flashlight, the viewfinder of a telescope, the jagged outlines of a bombed wall, the round windows in the door of a restaurant kitchen. Speech bubbles are made to coincide with pillars of cigarette smoke.

By the 1950s, however, Eisner seemed to have exhausted his own inventiveness. Denny Colt actually spent eight weeks in 1952 voyaging on the moon, in the company of some convicts; a few months later, The Spirit was discontinued. For the next twenty years, Eisner primarily produced cartoon-formatted technical manuals for the US Army. His notable creation of this period – during which the army which sent him on several research expeditions to Japan, Korea and Vietnam – was a certain Private Joe Dope, who verses GIs in the arts of ‘preventative maintenance’.

Meanwhile, in the late 1960s, the comic-book landscape was being altered by the ‘underground comix’ movement, led by Robert Crumb. Among Crumb’s most popular creations are the suave adventurer Fritz the Cat (whose conquests include a female ostrich and his own sister) and Mr Natural, a fountainhead of exasperatingly vague advice, outfitted in a Tolstoyan beard and smock; another recurring character is the cartoonist ‘R. Crumb’, a gangly fellow in glasses, whom we find engaged now in sadomasochistic sex acts, now in mailing his comics to Bertrand Russell (‘oboy oboy, hope he likes um!’). Crumb made comics out of the most heterogeneous and unheard-of materials – Jesus, eyeballs, Amazonian muscle-women in hot pants, humanoid pigs – and they came out in an intoxicatingly uniform jumble, as if you were looking into the prop room of someone’s subconscious theatre. As the Cubists transformed all people and things into multifaceted geometrical solids, Crumb transformed all people and things into bulbous, anxious masses. Everything appears to have been electrocuted: the people, the telephones, the sun. Crumb, like many Cubists, does not make the world more beautiful; but he does impress you with a unified subjectivity.

And in a way, unified subjectivity was what Eisner’s omnivorous, collage-like productions were all about: the digesting and reproduction of the entire world through a single vision. It was under the influence of Crumb’s autobiographical stories that Eisner produced apparently the first work to be marketed as a ‘graphic novel’. A Contract with God (1978), set in a Jewish tenement in the Bronx in the 1930s, attracted notice for its literary-memoiristic material, for the characters’ extraordinary facial elasticity, and for the driving, drizzling rain, reminiscent of liquid mercury, known to this day as ‘Eisenshpritz’ or ‘Eisnershpritz’.

Life, in Pictures includes five of Eisner’s more explicitly autobiographical comics, notably The Dreamer, which describes how Eisner managed against all odds, in the middle of the Great Depression, to establish a fantastically successful comic-book studio. The Dreamer tells the story – and provides one of the first examples – of a narrative medium originally developed for one kind of story (superhero adventures) and now being re-adapted for another kind (the cartoonist’s autobiography). In the process, we see that these two types of material are not so different as they may at first seem.

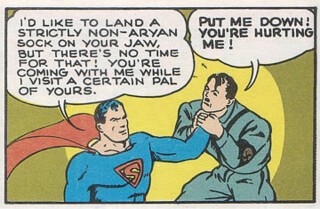

The most striking similarity between the superhero comic and the memoir-in-comics is the motif of ‘double identity’. This is perhaps the defining feature of the superhero. We recognise Superman not by his ability to freeze objects by blowing on them but by his second life as Clark Kent. In an essay on Superman, Umberto Eco characterised superhero comics generically as an amalgam of ‘mythopoeic’ and ‘novelistic’ narratives: Superman is simultaneously an epic-eternal hero who exists outside time (the Man of Steel), and a ‘consumable’ romantic-novelistic hero (Clark Kent) who gets older every week. These two types of hero also correspond to the double nature of the comics medium: a hybrid of words and pictures. Clark Kent, a print journalist, stands unmistakeably for the written word: beleaguered, bespectacled, clad in the newspaperman’s monochrome, he pales before the Technicolor splendour of Superman, who is the image made flesh, in all its immediacy and power.

What you realise, reading The Dreamer, is that the story of the superhero’s double identity is actually the story of American Jewish assimilation. In one spread, set in the Eisner & Iger studio, the cartoonists discover that they are nearly all Jewish. Eisner has changed their names, but a glossary at the back provides the key: ‘Jack King’ (né Klingensteiner) is based on Jack Kirby (né Jacob Kurtzberg), co-creator of Captain America and The Fly; ‘Ken Corn’ is based on Bob Kane (né Kahn), creator of Batman. The bespectacled Jews in their workshop, manufacturing superheroes under assumed names: it’s a room full of Clark Kents.

The Marvel powerhouse Stan Lee, who created or co-created such dynamos as Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk, The X-Men and Doctor Strange, was born Stanley Martin Lieber. And the first issue of Superman was published, in 1938, by two young American Jews, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. As Michael Chabon wrote in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000), whose protagonists are loosely based on Siegel and Shuster: ‘Superman, you don’t think he’s Jewish? … Clark Kent, only a Jew would pick a name like that for himself.’ Affinities have often been noted between Superman and mid-century American Jewry: there is the destruction of Superman’s family in a Holocaust-like disaster on Planet Krypton; the Kindertransport-like intergalactic journey to Earth; the deracinated childhood in Kansas. The fantasy of Superman was that, unlike much of American Jewry, he was not powerless and remote from the monstrous crimes being perpetrated in Europe: in 1942, a comic-book cover depicted the Man of Steel throttling Hitler.

Some American Jews, of course, lived a real-life version of this fantasy. Eisner’s next autobiographical comic, To the Heart of the Storm, set in 1942, opens with the newly drafted Eisner looking out the window of a train, recalling scenes from days gone by. He remembers his first experiences getting beaten up in the Bronx, his thwarted romance with a gentile girl and his friendship with Buck, the son of right-wing German immigrants, in whose basement the boys built a fully functional sailing boat. Years later, at the start of the war, Eisner runs into Buck in a New York cafeteria; the conversation gets off to an amiable start, until talk turns to the draft, and Buck assures Eisner that he has nothing to worry about: ‘Most Jews will avoid the draft! … Why do you think Hitler is trying to rid the world of Jews? … They don’t join up like we do!’ Crushed, the cartoonist leaves his friend in the cafeteria and strides out into the Eisenshpritz.

A few pages later, when a big publisher offers Eisner a chance to escape the draft, he turns it down: ‘I’ve spent the last five years drawing dreams … I’m my own prisoner … now is my chance to escape into the real world! I want to join the big parade … feel, taste and smell reality!’ The comic ends with the train pulling into an army training camp. In the last, full-page panel, the narrator marches off into a thunderstorm, in a line with the other army recruits; the illustration has no text and no border. The narrator is finally leaving the prison of his own finely inked lines. Leaving behind the bookish dreamer Clark Kent, he walks into the world of Superman.

If you look at the history of the comic-book superhero from the perspective of Jewish assimilation, one work that jumps out as a literary precursor is Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry story cycle, which appeared in Russia in 1926 (the first English translation was published in 1929). The cycle comprises 33 very short stories based on Babel’s experiences working for the Red Cavalryman, the newspaper of the Cossack army, during the Russo-Polish War of 1920. The Cossacks in the stories are superhuman figures, and not always well disposed towards the likes of Babel, a Jewish intellectual who goes through life with ‘autumn in his heart and spectacles on his nose’.

During the war, Babel, like his fictional protagonist, assumed a non-Jewish pseudonym: Lyutov, meaning ‘ferocious’. The fluctuation between Babel (the Jewish narrator) and Lyutov (his feral alter ego) is a theme in many of the Red Cavalry stories. ‘My First Goose’, the story of Babel’s first day on the job, opens with the journalist’s introduction to his new boss: ‘Savitsky, the commander of the Sixth Division, rose when he saw me, and I was taken aback by the beauty of his gigantic body. He rose – his breeches purple, his raspberry-coloured cap cocked to the side, various military orders pinned to his chest – splitting the hut in two, as a banner splits the sky.’ The gigantic human banner, the colossus in purple breeches, his chest thrust out beneath its spangled orders: Savitsky prefigures Superman, the image made flesh. Clicking his tongue at Babel’s spectacles – ‘here you get hacked to pieces just for wearing glasses!’ – Savitsky introduces the new recruit to his colleagues: illiterate Cossack toughs, who greet the intellectual by throwing his suitcase into the street.

At this point in the story the narrator transforms into the ferocious Lyutov. He stomps on the neck of a goose that has been waddling around the billet, impales it on a sabre, and demands that it be cooked for his dinner. Impressed, the Cossacks make room for him at the fireside and accept him as one of their own. But that night, after Lyutov retires to the hayloft with his five new comrades, he turns back into Babel: ‘I dreamed and saw women in my dreams, and only my heart, crimson with murder, screeched and bled.’

Babel made iconic the double identity of the assimilated Jew: a man of letters, striving to be a man of action; a man of words, striving to be a man of images. (In a story called ‘Line and Colour’, Babel contrasts the idealism of Alexander Kerensky, who refuses to wear glasses because he prefers colour to line, to the hardheadedness of Trotsky, who never takes his glasses off for a minute: colour is always an expensive commodity.) The Jewish American creators of the early superhero comics took up this dialectic of word and image, which was so well suited to both their artistic medium and their place in the world.

Red Cavalry was not, of course, the sole literary antecedent of the superhero narrative. One work frequently cited in this context is Emma Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1903): the story, set during the Terror, of a beautiful French actress married to a wealthy but vapid British baronet. The actress despises her husband and is greatly taken by stories of a nameless Englishman who has been rescuing aristocrats from the guillotine; every time he spirits another royalist to England, the public prosecutor receives a drawing of a scarlet pimpernel. The actress is naturally astounded to learn that the Scarlet Pimpernel is none other than her husband, who has assumed the persona of a gaping aristocrat in order to deceive the Jacobins. Many ingredients of the superhero comic are present here, notably the duality of the weak, drab man and the brilliantly coloured anonymous hero. What Babel adds is the suggestion that the superhero’s heroism has a diabolical element: to become a Red Cavalryman (if not a Scarlet Pimpernel) is to enter into a compact with the devil. Blood must be shed; geese must be sacrificed.

In Babel, the weak man is neither an idiot nor a play-actor; he is a bookish type who really is physically weak – and who has nonetheless created a kind of monster. As has been noted by both Eisner and Chabon, the conceit of the weak, bookish type who creates a valiant monster exists in Jewish folklore, in the legend of the golem. This was a creature formed in clay by a rabbi in 16th-century Prague to protect the ghetto from a pogrom. It grows to superhuman proportions and destroys the enemies of the Jews, although in most versions of the story the golem eventually turns on the Jews as well and has to be destroyed.

Babel’s other contribution to the comic-book tradition is a certain kind of narrative time: the time of the story cycle. There is a close affinity between the idea of the cyclical and the hero’s double identity. As both mythical hero and romantic-novelistic hero, Superman occupies two mutually exclusive kinds of time. As a mythical character, he is always engaged in conquering an endless series of obstacles; as a romantic-novelistic character, every time he surmounts an obstacle, he has, as Eco puts it, ‘made a gesture which is inscribed in his past and weighs on his future. He has taken a step towards death, he has got older, if only by an hour.’ The mythic hero neither ages nor accumulates experiences; his fate is immanent and always present. The romantic-serial hero, by contrast, may be taken up at any point by a staff of ghost-writers, any one of whom can see only a few episodes into the future.

How to reconcile these two kinds of time in the story of Superman? The least satisfactory option, Eco suggests, would have been to ignore the problem; to have Superman’s adventures begin each week where they left off the week before, ‘as happened in the case of Little Orphan Annie, who prolonged her disaster-ridden childhood for decades’. Instead, the authors of Superman ‘devised a solution which is much shrewder and undoubtedly more original’:

The stories develop in a kind of oneiric climate … where what has happened before and what has happened after appear extremely hazy. The narrator picks up the strand of the event again and again, as if he had forgotten to say something and wanted to add details to what had already been said.

It occurs, then, that along with Superman stories, Superboy stories are told, that is, stories of Superman when he was a boy, or a tiny child under the name of Superbaby.

This is a fairly accurate description of the working of time in Babel’s story cycles. The stories are not ordered chronologically: there are repetitions; some characters unexpectedly reappear in unlikely situations; others appear in one story and are never seen again. At the same time, each story is a self-sufficient unit: it really is a story, rather than a chapter in a Modernist novel. As the stories of Superboy and Superbaby are introduced only retrospectively, so Babel followed the Red Cavalry cycle with a Childhood cycle, set in Odessa in the early 1900s, about a bookish Jewish boy – implicitly, the future Lyutov. (Superman’s Hebraic-sounding birth name, Kal-El, resonates with the name Babel used to sign his first articles: ‘Bab-El’.)

Babel and Superman didn’t exactly invent the time of the story cycle; something very similar was already in use in the 1890s and 1900s. In narrating Sherlock Holmes’s adventures, Dr Watson typically purports to be extracting, from voluminous casebooks, various cases which can finally be brought to light. As Superman readers belatedly learn of the existence of Superman’s cousin and childhood companion, Supergirl, so Holmes fans learn only midway through the series that Sherlock has a brother, Mycroft. As in the case of Red Cavalry and Superman, the cycle technique serves to accommodate a generically hybrid hero, though one who is here divided between two characters: the mythic superhero Holmes, and the serial ‘journalist’ Dr Watson.

It was an important innovation on the part of Babel and the authors of Superman to collapse Holmes and Watson into one person – as if the pedantic doctor turned out also to be an amazing superdetective. (That Watson and Holmes were ‘secretly’ doubles all along is suggested by the fact that Conan Doyle, an ophthalmologist, based Holmes’s deductive abilities on those of a real doctor, the surgeon Joseph Bell.) Nonetheless, the hero-in-two-persons arrangement is vestigially present in many cyclically narrated comics. Probably the best-loved example is the duality of Snoopy and Charlie Brown. Snoopy, the romantic ‘hero’, is variously an attorney, a pulp novelist, an Olympic figure-skater, a Beagle Scout, Flashbeagle, the Lone Beagle, the Flying Ace, a World-Famous Golfer, a World-Famous Surgeon; while Charlie Brown is inescapably ‘the Charlie Browniest’ of all Charlie Browns. Charlie Brown is all talk and worry; Snoopy is all image and imagination. And an ‘oneiric climate’ just about describes the sense of time developed by Schulz. Seasons change, as do fashions: Snoopy is always on top of the latest fads, from contact lenses to grunge. But although new babies are occasionally born (Sally, Rerun), the existing children don’t get any older; and history always remains outside the frame.

Over the past twenty years, history has become one of the privileged subjects of the graphic novel. The image-text duality translates into a dual relationship to history: the hero is simultaneously a private cartoonist and a world-historical actor. This is the duality rendered somewhat simplistically in Satrapi’s Persepolis (2004); it is more subtly present in Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds (2007), a missing-person story set in present day Tel Aviv. The trend began with Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the first graphic novel to cross over into the literature market, in which the author memorably depicts himself at the cartoonist’s table, as a man in a mouse mask.

The suitability of the comics medium to historical narratives lies, again, in the text-image duality, which makes history a kind of imagistic backdrop to the characters’ actions. The superhero’s double identity corresponds, in this sense, to Lukács’s distinction between private citizens and ‘world-historical’ characters: Clark Kent (and Isaac Babel) represent text and private life, while Superman (and the Red Cavalryman Lyutov) represent the image and world-historical narrative. According to Lukács, the task of the historical novel is to use private destinies as a mirror of ‘social-human contents’, in order to ‘present history “from below”’. This is the aim so spectacularly achieved in Maus, whose first volume is subtitled My Father Bleeds History: this is history seen literally from below, from the perspective of the mouse.

In graphic novels today, Jewishness is often still the codeword, not only for double identity in general, but for a particularly historical double consciousness. This is the case even among non-Jewish cartoonists. A particularly striking case is that of David B. (né Pierre-François Beauchard), whose autobiographical L’Ascension du haut mal (1996-2003) is available in a single-volume English translation called Epileptic. The ‘epileptic’ is Pierre-François’s elder brother, Jean-Christophe, and the book tells the story of the Beauchard family’s quest for a cure for Jean-Christophe’s seizures. The children are dragged to hospitals, to Lourdes, to macrobiotic communes, to Swedenborgians and to witch doctors.

Pierre-François acts out his part in the family’s battle against epilepsy by obsessively drawing battle scenes, covering page after page with the minuscule dismembered corpses of samurai, Mongol horsemen and Aztec warriors. Meanwhile, Jean-Christophe develops increasingly autistic tendencies, and an embarrassing mania for Hitler: ‘Where I’m an anonymous crowd of Mongols,’ David B. writes, ‘he’s a supreme leader./His dream is that of an eternal parade by an army that worships him./He draws himself a Nazi flag and posts it on the wall of his room.’ In order to express his opposition to the sickness embodied by that swastika, Pierre-François assumes a Jewish identity. He is inspired by the discovery that his mother wanted to name him David but was dissuaded by her father-in-law, who found the name ‘too Jewish’. This same grandfather is the owner of a four-volume illustrated history of World War Two, much beloved by Pierre-François; until one day he flips to the end of Volume IV, and sees, for the first time, photographs of the victims of the concentration camps. One prisoner is depicted in the same tortuous posture adopted by Jean-Christophe during his epileptic seizures: the contorted body, the craning neck, the claw-like hands. The next time Jean-Christophe starts talking about Hitler’s genius, ‘David’ tackles him, declaring: ‘Me, I’m a Jew!’

Pierre-François’s mother does not object to his desire to change his name to David. ‘I would’ve liked to be Jewish,’ she explains: ‘All the best writers are Jewish … or homosexual./Or both! Marcel Proust is extraordinary.’ ‘David’ is puzzled by his mother’s confidences: ‘Is she trying to tell us that she’d have liked to be a great writer?’ David, of course, would like to be a great writer; and, having adopted a Jewish identity, he begins to undergo an artistic metamorphosis as well. He draws his first comic book – a dramatisation of Tamerlaine’s sallies in Central Asia, complete with elaborately lettered speech balloons – but discovers that battle scenes have lost their appeal for him; he realises that Genghis Khan had left mountains of corpses in Peking and Samarkand. Abandoning Tamerlaine after only twenty pages, he instead embarks on reading his ‘very first grown-up book’: Gustav Meyrink’s The Golem.

He becomes obsessed by the golem and by Jewish folklore; his first serious girlfriend is a Jewish singer (‘She performs the traditional Yiddish and Judeo-Hispanic repertory’) with whom he moves to the rue des Rosiers, in Paris’s old Jewish quarter. The couple spend years vainly trying to conceive a child, before drifting apart; the fertility doctors announce that David’s sperm are inexplicably bifurcated: ‘Each of them has either two heads or two tails … Am I a double myself?’

Pierre-François Beauchard’s double identity as David B. is a mirror image of Isaac Babel’s double identity as Konstantin Lyutov. Babel exchanges the pen for the sword; David B., coming to understand suffering and victimhood, gives up his battle scenes – and changes his name to hide the fact that he isn’t Jewish (that B. could stand for anything: Blumenkrantz, Bernstein, Berkovits). By assuming the name of a Jew, he attempts to join the privileged literature of otherness: ‘All the best writers are Jewish.’ David B. isn’t the only instance of a well-known cartoonist publishing under a false Jewish name. The Canadian cartoonist Seth was born Gregory Gallant – a name any superhero would have been proud of. Gallant changed his name to Seth – no surname – in his twenties. In his semi-autobiographical ‘picture novella’ It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken (2007), Seth portrays himself wearing glasses, a fedora and a trenchcoat. ‘Get a load o’ that guy,’ a teenager remarks at one point: ‘It’s Clark Kent.’

In recent years, the theme of Jewishness has been interestingly appropriated by a new group of graphic novelists: Asian Americans, most notably Gene Luen Yang and Adrian Tomine. For Yang and Tomine, the canonical writer of Jewish assimilation is Babel’s American heir, Philip Roth, who transplanted the sphere of action from war to dating. Yang’s American Born Chinese (2006) relates the adventures of a Chinese boy called Jin Wang who so longs to be attractive to white girls that he manages to sublimate himself into a blond all-American boy called Danny, who is, however, pursued by a monstrous double called ‘cousin Chin-Kee’, a bucktoothed, pigtailed personification of yellow peril stereotypes.

Tomine’s Shortcomings, which explores similar issues in a more realistic mode, opens with the protagonist, Ben Tanaka, watching a movie about a Chinese American girl’s evolving relationship with her grandfather: ‘As I stood beside him in his ageing fortune cookie factory … I realised that he was very much like the thing he’d spent his life making: a hard, protective shell containing haiku-like wisdom.’ Ben takes no pains to hide his low opinion of both the film and the festival presenting it, which was organised by his girlfriend, Miko, to showcase San Francisco Bay Area Asian American digital filmmakers (‘Didn’t they also have to be left-handed or something?’). Miko accuses Ben of being ‘ashamed to be Asian’; ‘after a movie like that,’ he retorts, ‘I’m ashamed to be human.’

These first pages display Tomine’s strengths: exquisite draftsmanship, witty repartee and a pitch-perfect ear for the well-intentioned nonsense produced by youthful idealism; it is hard not to admire that ‘ageing fortune cookie factory’. Also in evidence, however, is the profound unlikeability of all Tomine’s characters, who are distributed between two unappealing camps: sarcastic misanthropes (Ben) and humourless cliché-mongers (Miko). In the next pages, Miko, exasperated by Ben’s anti-Asianness (at one point she finds a DVD in his desk called Sapphic Sorority and is appalled that it features only white women), decides to spend the summer in New York. Alone in Berkeley, Ben embarks on the time-honoured Rothian quest of bedding the shiksa.

Step one: the oversexed intellectual must mock the shiksa for some manifestation of Wasp frivolity. It isn’t long before Ben finds himself in the apartment of a blonde ‘performance artist’, whose walls are covered by Polaroids of her urine-filled toilet bowl. ‘I wake up every morning, go pee, then take a picture … Patterns start to emerge … like when I’m dehydrated, or when I get my period … it’ll be a huge installation someday.’ ‘That’s pretty amazing,’ Ben says. The pee-installation is, presumably, evidence of Tomine’s deft comic touch. But the only humour Ben draws from the situation is the mordant recognition of his own shallowness: for a chance to score with a white girl, he really was willing to feign interest in this vulgar pseudo-art: ‘My superficiality could’ve overpowered my snobbery.’

Step two: self-congratulation. ‘The eagle has landed,’ Ben announces, with the deed accomplished. Like a Roth protagonist, Ben does not hesitate to communicate to the shiksa how pleased he is with himself, as one of his kind, to be dating one of her kind. When Ben and the white girlfriend pass some Asian teenagers in the street, Ben insists that one of the boys was staring at them in ‘white-girl envy’. ‘Now if he had been with a white girl too,’ Ben continues, ‘we would’ve given each other the sign … kind of like a covert “high five”.’ Tomine doesn’t leave out the penis envy, either. Where Portnoy’s ‘circumcised little dong … shrivels up in veneration’ when confronted with an actual shiksa, Ben suffers the even worse plight of being an Asian man and thus having an irremediably small penis. This is the subject of three pages of sporadically entertaining back talk between Ben and his best friend, Alice (‘How small are we talking here? Like, in inches? … Your refusal to answer only damns you further!’).

Meanwhile in New York, the hypocritical Miko turns out to have been having a fling with a white guy, whom she perversely defends against charges of whiteness: ‘He’s half Jewish, half Native American.’ Ben scoffs at this – ‘That’s hilarious! Is that what he put on his college application?’ – and indeed Shortcomings works in part by deflating American Jews’ continued status as cultural outsiders. From Ben’s perspective, Jews, half-Jews and half-Native Americans are all just white people.

Where David B. makes sense of his own feelings of alienation by ‘becoming Jewish’, Tomine’s characters set out to knock Jewishness off its pedestal. In the four decades since Portnoy’s Complaint, Tomine implies, the battleground of erotic assimilation has been relocated. Nowhere is this clearer than when Ben and Alice, having arrived in New York to spy on Miko, take the subway to Brooklyn. Alice points elatedly at the Brooklyn Bridge: ‘Doesn’t it make you feel like you’re in some nostalgic movie about being Jewish or something?’ Alice is happy to feel her life intersecting with the set of a ‘nostalgic’ Woody Allen movie, because the American Jewish narrative offers a chance to fit her own idiosyncratic and often uncomfortable personal experience into an already meaningful story – one which, moreover, has a built-in happy ending. From the perspective of Ben or Alice, the Jewish assimilation narrative is especially powerful because its practitioners have by now been so seamlessly integrated into mainstream American culture.

Unlikeability and self-hatred are by no means anomalous traits in the protagonists created by today’s younger male cartoonists, the ‘young fogeys’ whose relentless portrayal of unattractive qualities and male insecurities, often combined with extremely beautiful and technically accomplished artwork, does not always make for enjoyable reading. Some graphic novels give you the impression of being stuck in conversation with a self-hating man who constantly harps on about his most unappealing qualities, less in the hope that you will protest – if you do, he will start arguing with you – than to make you feel shallow for not liking him. Apparently, only superficial people choose their friends exclusively from the ranks of the pleasant or attractive, rather than from among introspective guys who tell it like it is. The most extreme example is Ivan Brunetti, who has taken male self-loathing to incredible extremes; he deserves recognition just for thinking of all the awful things he writes in his books.

Brunetti and his colleagues are often praised for their ‘unflinching’ or ‘uncompromising’ honesty, and this is, I suppose, a valid criterion; if guys are really experiencing all these painful emotions, then who am I to say that art shouldn’t be the mirror of reality? On the other hand, what one objects to in Brunetti is less the self-loathing than the attendant cocktail of self-congratulation and dime-store psychology. ‘Why would a girl like Kim even care that I didn’t call her back – me, a guy who is chronically constipated and probably has cancer? She could have any guy she wanted. I dunno … maybe it’s the mothering instinct … maybe all mothers wanna sleep with their sons or something.’

OK, I made that up; but this really is taken from a gorgeously illustrated page in Brunetti’s Misery Loves Comedy:

Back to this androgyny thing … maybe androgyny is like, I dunno, an idealised merging or a perfect synthesis of the duality of sexual nature … or maybe not … all I know is that I’m still infatuated with this one lesbianish girl I saw in an ‘Omni’ supermarket about six months ago. She caught me ogling her, and she sneered at me … Valerie noticed me staring at her, too … I think Val was peeved …

The most despised of all men, he is still coveted; his wandering eye still has the power to make a woman feel bad about herself. This is another recurring motif in the ‘self-hating male’ graphic novel: the depressive cartoonist manages to score with a woman out of his league, and then loses her thanks to his own boorish behaviour. The woman goes off somewhere with her deflated ego, leaving the cartoonist to his moody introspection, dot dot dot.

Misery Loves Comedy includes a page of letters signed by fellow cartoonists: ‘It was as if this had been written for ME’ (Jim Siergey); ‘I enjoyed watching you suffer – keep on whining!’ (Art Spiegelman); ‘After reading your comic book, I had the overall impression that maybe I wasn’t such a bad guy overall’ (Chris Ware). (Robert Crumb’s letter is welcome evidence that humour can still be found among the self-haters: ‘I suppose I have to take part of the blame for encouraging this sort of thing in the comics,’ Crumb writes. ‘Your comic was sharp and funny and well-drawn, but so fucking negative and self-absorbed, it’s hard to take.’ Addressing Brunetti as ‘Bubbela’, Crumb goes on to recommend a programme of Prozac and ‘Positive Autosuggestion’.)

But if you don’t already think you’re ‘such a bad guy overall’, other books that weren’t really designed with you in mind include Chris Ware’s exquisitely designed Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth (2000), a masterpiece of sadomasochism on every level: the lettering is so small that it is painful to read. The book opens with a retro-styled ‘Technical Explanation of the Language’, complete with a multiple choice self-test, printed in type smaller than the most compact OED. The first question is ‘You are: (a) male; (b) female’ – beneath which is printed, in still tinier letters: ‘If (b) you may stop. Put down your booklet. All others continue.’

The misanthropic graphic novel doesn’t have to be self-indulgent or misogynistic; the proof is Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World (2000), which has all the sarcasm and one-liners you could hope for, but put into the mouth of two teenage girls, Enid Coleslaw (an anagram of Daniel Clowes) and Rebecca Doppelmeyer (referred to as ‘that Rebecca Doppelgänger’). In the tradition of the comic-book double identity, Enid is Jewish and wears glasses, while Rebecca is a ‘skinny blonde Wasp’. Anyone who crosses Enid and Rebecca’s path is instantly and mercilessly labelled: a loser, a Satanist, a ‘total date-rapist’, ‘an annoying crack addict’, ‘a pseudo-Bohemian art-school loser’ etc. But the girls practise this rapid-fire naming with all the irrepressible joy – and none of the pedantic dourness – of collectors. Part of their camaraderie consists of constantly looking out for interesting specimens to show each other; with the most limited of suburban materials, they create a world of curiosities. ‘You have to see for yourself, it couldn’t be better,’ Enid tells Rebecca in the supermarket, dragging her over to see the shopping cart of the ‘Satanist’ they have been following, which is (gasp) completely full of Lunchable-brand packaged lunches. The contrast between Ghost World and Shortcomings is immediately visible: Enid and Rebecca would have appreciated the girl who photographed her own pee every morning.

Clowes has a rare talent for exposing the precariousness of these comic escalations, which can collapse in an instant, the hilarious transforming into the banal. ‘That wasn’t as much fun as last time,’ Rebecca says of the girls’ second foray to Hubba Hubba, the Original Fifties Diner, at the exact midpoint of the book, which marks the beginning of the decline of their friendship. Enid wants to go to college and ‘become a totally different person’, while Rebecca imagines the duo ‘always staying together’, ‘acting like this when we’re thirty’. The book loses steam at the end, fizzling out with an unconvincing love triangle; but the unsatisfying ending is, in a way, a function of form: Rebecca and Enid are ‘cyclical’ characters, transplanted into novelistic time. Nothing good lasts for ever.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.