There are few enough points of continuity between the official state ideology of Maoist China and the ideology espoused by the country’s leaders today. But the significance of Qin Shi Huangdi, First August and Divine Emperor and subject of the outstandingly popular BM exhibition, The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army, might be one of them.* In the mid-1970s he had a starring role in one of the more bizarre movements of the Great Helmsman’s fading years. This was the so-called Struggle between Confucianism and Legalism, an attempt to recast the whole of Chinese history into a Manichaean conflict between two ‘lines’. You had the Confucian bad guys (humanist, conservative, capitalist) and the Legalist good guys (harsh authoritarian proto-socialists, with History on their side). ‘Burying the Confucians and burning the books’ – for which the First Emperor had been excoriated by centuries of historians – was now reconfigured as the forward-thinking decisiveness necessary to crush backsliding and ensure the victory of the correct line. The modern, slightly (but not much) subtler version of this appears in Zhang Yimou’s 2002 film portrayal, Hero. There, the emperor voices in impeccable classical Chinese the sentiment that you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, or, to put it differently: the deaths of many are a necessary part of China’s rise to Unity and Greatness. The ‘resistance is futile’ film clips of the all-conquering armies of Qin, projected onto the walls of the Reading Room, look as if they use some of the costumes from the movie. Underneath the visitor’s feet are the old library desks, one of which was arbitrarily decided by curators to be ‘Marx’s seat’, in order to satisfy the curiosity of pious delegations from the East; not so very long ago, either.

So it’s hardly surprising if commentators pick over the import of this exhibition and make analogies, for better or for worse, with modern China, in a way that simply does not happen with other shows of such ancient archaeological material. The critical reception of the exhibition is quite different from that accorded to the contemporaneous Tutankhamun show at another, now much altered Dome. Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs (O2, until 30 August) is not scrutinised for what it might say about Egypt now, or for portents of Middle Eastern outcomes. There is a curious effect here, with China being given only two moments in history – ancient ‘then’ and modern ‘now’ – thereby rubbing out the need to get to grips with all the bits in between, the parade of similar-sounding dynastic names that fill up the centuries: Han, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing. The collapse or elision of the two millennia separating the First Emperor’s ‘then’ from Hu Jintao’s ‘now’ is figured in the exhibition by a case in which the head of one of the clay figures is juxtaposed with a life-size portrait photograph of Ma Yang, the man who sank the well that led to their discovery. This was back in 1974, when the Party line would have been deluging him and his fellow villagers with stuff about the Confucian/Legalist struggle, through an official sequence of dynastic history and philosophers’ names that may have been only fitfully meaningful to them. In 1974, Ma Yang was a ‘peasant’, in the vanguard of the Maoist version of class struggle; now the label describes him as a ‘farmer’, the translation of the same Chinese word favoured by present-day official discourse. Their new-found contemporaneity is what makes the Terracotta Army available to such events as the lone protest over China’s CO2 emissions: early in the exhibition’s run, a man climbed over the security barriers and draped the figures in the paper dust masks necessary to survive the atrocious air which is a result of China’s exploding economy.

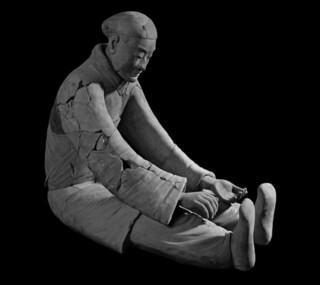

I saw the exhibition first at a session for schools. For these children the Terracotta Army was just something that had always been there, the period of its excavation as remote as the Qin dynasty itself. Two boys sat in solemn silence on one of the curiously ‘designed’ benches, transfixed by the film playing over their heads. A bit of light flirtation went on in the gloom. Many sketched diligently on their worksheets, a few sitting off to one side where they could get to grips with the intricacies of the hairstyles, but the great majority preferring to cluster in front of the long rectangular formation in which the 17 figures are displayed, so that the army seemed to be marching towards them. Sharing this perspective created a frisson of threat – ‘The Chinese are coming!’ – but one made manageable by the figures’ rigidity. They are not coming at you, but standing. Maybe that seems a greater threat still. At the end of their hour the schoolchildren were ushered out and the paying audience came in, largely middle-aged and middle-class and culturally much more homogeneous; the sound level dropped to the standard respectful museum-goer mutter as they made their way systematically from case to case.

The life-size human figure is a relatively rare presence in modern accounts of Chinese art. The figures therefore fill a gap that Chinese culture never knew it had, but one which has bedevilled the construction of ‘Chinese art’ as a category – by Chinese as much as by Western art historians – since early in the last century. If the Western tradition is taken as the norm, and if the foundational moment of that tradition is in classical Greece and Rome, then the ‘lack’ of the human body as a central subject of ‘Chinese art’ requires explanation. The photos you see as you go into the exhibition, which inscribe it into a unified ‘world archaeology’, are of the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, Hadrian’s Wall and the Mayan pyramids. All of these sites, and the cultures that produced them, are encompassed within the British Museum, some more comfortably and less contentiously than others. Most contested of all of course is the Parthenon, whose marbles are only a small part of the museum’s holdings of Greek and Roman sculpture of the human figure, part of its charter of existence. Their presence contains multiple ironies, one of them being that this foundational category of ‘art’ is situated in an institution that doesn’t present itself as an ‘art museum’.

The First Emperor was certainly widely reviewed by art critics. Treating the figures as art allowed Laura Cumming in the Observer to find it impossible to believe that their faces are not portraits, quite possibly self-portraits. This may be a more comforting tale to tell than the one to which scholars of this material generally subscribe: that the use of a system of ‘module and mass production’ accounts for the diversity. The phrase was coined by the German art historian Lothar Ledderose in 2000, when he used it as the subtitle of his book, which had an image of the Terracotta Army on its cover and contained a compelling thesis about the distinctive nature of creativity in China. Most commentators have picked up on the mass-produced nature of the figures; a display case in the exhibition shows a modern reconstruction in little clay figures of the production line. It is modelled in the style of the Socialist Realist sculpture that was used in Mao’s day to generate such vast agitprop dioramas of life-size figures as Rent Collection Courtyard (portraying the ways of pre-1949 ‘evil landlords’) or Wrath of the Serfs (portraying the ‘evil ways’ of the pre-1949 Tibetan monastic establishment). The point is not just mass production but the mass production of modular forms – three types of plinth, two types of leg set, eight types of torso and so on – which can be combined and recombined and combined again into a simulacrum of diversity. This is not so much mass production in the sense of the Industrial Revolution as in the sense in which it is deployed by Starbucks, where everyone can think they are getting just what they want.

Ledderose’s analysis of module and mass production in Chinese culture extends across a range of phenomena, one of them being the Chinese script, where again a relatively small number of modules can be combined to generate forms running into tens of thousands. The contemporary artist Xu Bing used the same principles to generate thousands of unreadable characters in A Book from the Sky of 1987-91. And it is the Chinese script that dominates the first half of the BM exhibition, in the form both of actual objects and of projections and photographs of larger inscriptions dating to the First Emperor’s time, such as those carved in huge characters on the face of sacred mountains. For an East Asian audience, these ancient but still readable inscriptions are much more compelling than they are in London; when a broadly similar exhibition was shown in Tokyo, much more space and attention were given to this aspect of Qin Shi Huangdi’s policies of linguistic standardisation. The codifications of the Chinese script that took place under his brief reign are so significant that their principal architect, the minister Li Si, remains an honoured figure in histories of calligraphy, despite being a Bad Man in terms of dominant later ideologies.

But the division of The First Emperor into two distinct halves, the first dominated visually by script and the second by the human body, should not obscure the homologies between them that run through Chinese culture. This relates not just to their shared modularity, but to the ways in which the human body provided the metaphors through which the script, and hence culture itself, could be valued and validated. Good calligraphy has ‘bones’, its ‘sinews’ are taut; weak calligraphy is ‘flabby’, ‘fleshy’. The separation of Flesh and the Word might be a central image of those cultures clustered round the Mediterranean, or at least a key belief of Christianity, but it is their oneness that came to the fore in China over the millennia since the tomb of the First Emperor was sealed. Both need consideration if the past and present import of that tomb and its contents are to be grasped today.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.