The emperors in question in the exhibition China: The Three Emperors 1662-1795 (at the Royal Academy until next April) are Kangxi (ruled 1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-35) and Qianlong (1736-95). The hard-to-pronounce imperial names were avoided in the exhibition’s title, but the show has a Chinese title which is prominently displayed in the publicity material. Sheng shi hua zhang is a sonorous and vaguely archaic-sounding phrase which means something like ‘Splendours of an Age of Prosperity’, apt for the Qing era when the Chinese emperors ruled the largest and most populous empire on the globe. It is also a term with contemporary resonances, widely used to describe such phenomena as a new motorway bridge over the Yangtze River, or swanky golfing parties in Shanghai hotels. It was the title of a dance festival, compered by People’s Liberation Army choreographers, ‘offered’ to the Communist Party in celebration of its 80th anniversary in 2001.

It would be too easy to see this exhibition, which has obtained from the Palace Museum in Beijing an unprecedented group of works of art (paintings, textiles, porcelain, even a great rock from the imperial gardens), as the tribute of one age of prosperity to another. It would be easy, too, to see some contemporary parallels: the high Qing was an era of the firmest possible central control over the lands of Islamic Central Asia and Tibet; its emperors eagerly accepted advanced technology from European Jesuits at their court while affirming China’s enduring cultural values; they instituted rigorous ideological control while encouraging their subjects to prosper materially; new millenarian religious sects were vigorously suppressed. On the other hand, Qianlong would certainly have been baffled by the notion that art and politics don’t mix, so why should we affect to be surprised if the modern Chinese state deploys its curatorship of past cultural treasures to send subliminal messages?

It is inevitable that this contemporary relevance will be gestured at by anyone trying to make the exhibition ‘meaningful’. But this is the old Orientalist/Sinological trap, whereby anything Chinese stands for ‘China’ as a whole, and everything is connected to everything else. The objects and images on display at the Royal Academy were made to address their own audiences and needs, and it is patronising to make them serve ours too blatantly. Few of those who go down the road to see Rubens at the National Gallery will tease out the parallels between Rubens’s diplomatic career and the European Union. His work does not have to bear that load. As well as learning to pronounce their names properly, we have to let the Qing be the Qing.

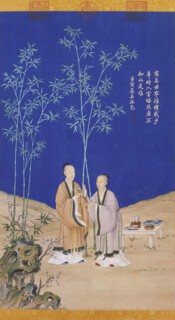

One way to do that is to see the objects and images here on their own terms. Many of them are very big, even colossal, confounding popular expectations of delicacy and miniaturism. Many of them are also ravishingly beautiful, from a simple green teapot, not previously exhibited, which had hardened curators sighing with delight at the press view, to a much reproduced if hardly ever seen set of paintings of 12 courtly beauties passing the time in various states of nervy languor. But even the huge equestrian portrait of Qianlong, done by the court Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione, partly on the model of Titian’s portrait of Charles V, invites a nose-to-the-glass viewing that rewards you with a sumptuous visual surface of horse and silk and armour.

Many of the scrolls produced in the milieu of court culture are like the miniatures which proved so beguiling in the recent Turks exhibition at the Royal Academy, but on a massive scale. They invite questions about how such pictures were used in their original context; we are not dealing here with Holbein’s great icons of Henry VIII, or the monumental portraits of rulers which were the stock-in-trade of court artists in Europe from Velásquez to David. As the near pristine condition of many of them implies, portraits of the Qing imperial court were not designed for permanent hanging (they are watercolours).

At what events were they originally viewed, and by whom? The imperial image was not disseminated to a wide audience in Qing China any more than in earlier periods; it did not appear on coins and was not reproduced in printed form, even though the technology existed. The picturing of imperial grandeur was intended for a very restricted gaze, perhaps only for the sitter himself. This is especially true of a set of miniature album leaves of Yongzheng, for example, which depicts him in 14 contexts of fantastic masquerade, rich in hermetic meanings for a man who was one of the most chronically suspicious and private of imperial personalities. As a Daoist monk, he conjures a dragon from roiling waves; as a moustachioed simulacrum of Louis XIV, in imported European finery, he spears a small tiger which appears baffled by this transcultural apparition.

Masquerade emerges from this show as one of the intriguing modes of Qing court culture, a ludic but not humorous probing of appearance and reality through dressing-up and posing, most clearly seen in a scroll in which Qianlong seems about to replicate himself pictorially to infinity, and where the emperor’s own inscription explicitly poses the question: ‘Is it/is he/am I one or two?’ There are objects as well as images here which seem to bring us close to the imperial individual: the wooden blocks, for example, that Kangxi used to affect an interest in the principles of Euclidean geometry – was this, too, a form of masquerade? One of the show’s great successes is that it manages to give a proper place to the Jesuit savants and artists at court, without becoming overexcited to the point at which they, and not their imperial employers, become the main story.

Possibly the most innovative section of the exhibition is the collection of mostly monochrome images produced away from court for the delectation of a cultured elite. The set of ten album leaves of Insects, Birds and Beasts painted in 1774 by Luo Ping takes to an extreme an aesthetic of less is more: on one leaf, two spiders huddle in the top-left corner of the otherwise blank sheet. The extent to which such work is a conscious refusal and critique of the aesthetic of the imperial court is only one issue raised by a careful reading of the pictures. And here ‘reading’ is not a fashionable linguistic metaphor. Educated Qing men and women would themselves have used the term du hua, ‘reading the painting’, for the close and prolonged scrutiny which can be hard to achieve when visiting an exhibition, but which here will be well worth the effort. They would have applied it to images they considered to be ‘paintings’, hua, but not to all the images displayed here, some of which might have been relegated to the broader and less discriminating category of ‘pictures’, tu, shading off into mere illustration. The distinction between tu and hua was important in Qing aesthetics, as was that between two other categories much on display here: gong, ‘craft’ or ‘intricacy’, and zhuo, literally ‘clumsiness’, but in aesthetic terms meaning something like ‘sincerity’. The achievements of gong were never higher in China than during the 17th and 18th centuries, and this exhibition puts on view a grouping of its masterpieces which is unlikely to be seen here again.

It is exactly 70 years since a major Chinese show at Burlington House last displayed such work: it failed to enchant Modernist sensibilities which, in the manner of Roger Fry, were excited by Chinese art of a much earlier period. Also, the Qing dynasty was then within living memory, and occupied an uncomfortable place in Chinese modernity, which was founded on its overthrow. Now perhaps both Chinese and Western audiences are ready to see both craft and sincerity. In London, we won’t get a better chance.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.