In August 1914, France mobilised jubilantly. ‘La Patrie’ was in danger and men and women of all classes and stations rallied to its defence. Florid voices on the clerical, aristocratic, conservative right defined patriotism grandly, as a mystical religion rooted in the land. Others, more worldly but no less exalted, were clear that patriotism was a hard-won secular tradition under constant threat from socialism, collectivism, anarchism, internationalism, individualism and now, most urgently, from the latest migration of Teutonic barbarism. When war broke out, President Poincaré’s call for an end to internal division and ideological strife was universally accepted. Politicians, intellectuals, civil and religious leaders sank their differences and rose as one to declare that serving France was an obligation, a duty, a privilege.

Gung-ho chauvinism and righteous indignation proved difficult to sustain. As the number of front-line casualties rose, the initial heroic roar was cut short, like the cavalry on whose dashing image it had largely been based. Three million Frenchmen donned uniform in August. By the end of September, 300,000 of them were dead, more than a fifth of the 1.3 million French soldiers who would die during the years 1914-18. By late November, the number of dead, wounded and missing stood at nearly 600,000.

The story of what happened next has been told in different ways: in terms of aims, strategy, chronology, equipment, battles, causes and effects. When the German advance was halted, the Allies and the Central Powers settled into a war of attrition, with positions defended and taken, with minute territorial gains paid for by terrible loss of life. In 1917, after Verdun and the Somme, there were mutinies in the French trenches against incompetent military leadership, and strikes at home over spiralling prices. The news got worse – the rout of Italy and the need for a new Italian front, Russia’s withdrawal from the war after the October Revolution – before it got better, with the arrival of American troops in numbers in the summer of 1918.

For Martha Hanna, however, to look at those years only through the usual ‘wide-angled lens’ is to miss crucial dimensions of the human reality underlying the war effort. The French were sorely tried. The jingoism of 1914 was followed by quiet confidence in 1915; anxiety in 1916, when months kept being added to forecasts of the length of the conflict; despondency in 1917, when it seemed to have no foreseeable end; and severe loss of heart in the summer of 1918. Yet combatants and non-combatants alike remained steadfast in defiance of the facts. Even through the dark days of 1917, there was general agreement that France must be defended. Was the cement that held the French together the union sacrée or the intellectual, spiritual and political leadership they were given? Some historians take the view that the stoicism of soldiers who concealed the realities of modern warfare from their friends and family insulated the civilian population against the worst of the horror and thus made the situation bearable.

In Your Death Would Be Mine, Hanna tests this assumption. She shows that, in their letters and during their leaves, soldiers did indeed tell those back home about the hell of trench warfare. When the surprisingly efficient postal service hit its stride, four million letters to and from the front were sent each day, ten billion in all by the end of the war. Many collections of letters home from front-line soldiers have survived, but the answering letters, giving the view from the domestic front, are far rarer. Using ‘a microscopic lens’, Hanna exploits a unique cache of two thousand letters exchanged between a private soldier from South-West France and his wife, a correspondence that covers the war years and ends only with his demobilisation in July 1919. Rather than publishing a selection of the correspondence, she makes the letters the focus of her account of an intimate relationship, and contextualises it by reference to the current state of hostilities, the conduct of the war, the social and economic conditions on the home front, and the general minutiae of daily life. The result is a vivid picture of the Great War seen from below which illustrates the view, popular now for a generation or so, that it is not events but people who make history.

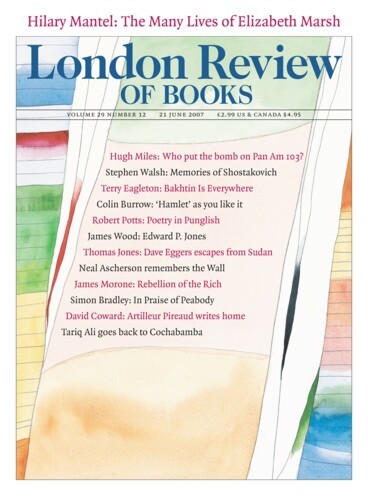

Paul Pireaud was born in 1890 and raised in the farming commune of Nanteuil-de-Bourzac (population 485) in the Dordogne. A child of the secular Third Republic, he was given a free elementary education and between 1911 and 1913 completed his military service, part of it in Morocco. In February 1914, he married Marie Andrieux, who was 21; he was mobilised on 2 August. The couple were accustomed to separation and resumed the correspondence they had begun in 1911.

At first Paul stayed clear of danger. Though he had cavalry experience, he was assigned to the Army Service Corps, where he made bread and looked after the horses. It wasn’t glamorous but it was safe, and he avoided the massacres of the first months of the new mechanised warfare. At the end of 1915, he was transferred to a newly created artillery regiment, with which he saw action at Verdun and the Somme; he later served with the Tenth Army at the Chemin des Dames in 1917 and then went with the French Expeditionary Force to Italy, where he was when the Armistice was signed. Again, he accounted himself fortunate. As a gunner, he stayed out of range of the enemy’s machine-guns and his chances of survival were accordingly higher than those of the troops in the trenches: 85 per cent of the French dead were infantry.

He did not hide from Marie the fact that modern warfare was unimaginably awful and described it in terms which she could not have found reassuring. His frankness was a measure of the brutalisation of front-line troops. Living at battle pitch for extended periods, he acquired front-line standards for judging the noise, the fear, the savagery. ‘Here,’ he wrote from Verdun in May 1916, ‘it is extermination on the ground.’ He told her about the never-ending artillery duel, the comrade who was cut in two by shrapnel, the gas attacks, the dismembered, stinking corpses of horses – everything that newsreels, photographs, newspapers and novels would make familiar to later generations. Occasionally there is a touch of gallows humour, as when we learn that shells were known as ‘prunes’ for the loosening effect they had on the bowels. But more often there was incomprehension at the scale of the killing, and anger towards journalists, visiting dignitaries with medals and uniformed non-combatants behind the lines who had it cushy. Mostly, Paul’s life consisted of feeding shells into the breech of 75mm French guns and dodging those fired back by the enemy, whose bigger cannon and howitzers had a longer range.

He took heart in April 1916, when Pétain famously said: ‘Courage! on les aura!’, words he repeated in his letters home, never seriously doubting the outcome. His reason for fighting was to defend Marie, his ‘Marquise’, and Serge, the ‘petit ange’ born in 1916, and his small piece of the Dordogne. He was not interested in international politics, though he hated the Germans, whose fault it all was, despised the Bolsheviks for pulling Russia out of the war, the Italian army for running away, and US doughboys for making free with French women. Eventually, he became battery messenger and a batman in the officers’ mess (waiting on them was safe but made him feel servile). He learned to drink, waited impatiently for leave, wrote a letter every day and expected one in return.

Letters, like the food parcels that supplemented the often dismal rations, were a reminder of his civilian identity. Marie sent kisses, encouragement, news of which of his village friends were missing, wounded or dead. She told him about a woman from a neighbouring village, Maria Fabas: when the mayor learned that her husband had been killed he didn’t have the heart to tell her, so poor Maria went on hoping while everyone else knew the truth. Marie passed on rumours that identified anyone with a car as a German spy and reported on the work of the farm, which fell increasingly on her shoulders.

This last was a major alteration in the fabric of rural life. Conscription and the requisitioning of animals and chemical fertilisers for military use made land-work more difficult for the women and the old men who were left to do it. Conversely, allowances were paid to servicemen’s families and the money economy at last reached the countryside. Material life thus changed both for the better and the worse. Marie, who had bought her blouses at local markets in 1915, was sending away to Paris for them long before 1918. But while prices for farm produce rose, these gains were offset by spiralling inflation after 1916. And as agricultural production fell, bread rationing was introduced, at a level suitable for city office clerks but not for those doing physically demanding farm-work. On the credit side, though Hanna does not mention it, game thrived in the absence of hunters and filled many domestic pots.

Hanna picks up strongly on the couple’s growing self-confidence, which was shown in the way they coped with the altered circumstances of their lives. Paul was obviously better placed to widen his horizons through his close contact with men from other backgrounds and other parts of France. He learned how to speak to the officer class, and picked up useful information, which he passed on to Marie in his letters, when he was home on leave and during her visits to him when he was stood down from front-line duty. These conjugal visits had been banned, but the ban was routinely ignored by men and officers. Marie braved expensive, uncomfortable and unreliable trains to snatch a few days, sometimes weeks, with her husband. It was on one such visit that she became pregnant. Paul solemnly warned her against local quackery and old wives’ superstitions and urged her to consult the doctors whom she could now afford. Whereas local wisdom recommended pregnant women to eat carrots for a boy and onions for a girl, Paul encouraged Marie to read books (she probably owned the child-rearing manual of Adolphe Pinard, the Dr Spock of his day) and place her trust in science. Married comrades from towns said their wives had been told to drink milk: Paul bullied his father into buying a cow. As names for the baby, born after a long and painful labour (‘Oh, how I suffered, my poor Paul’), Paul suggested either Verdun or Paulette, depending on its sex, thus rejecting the tradition of honouring its grandparents. Marie went further still and chose, even more boldly, Serge.

He proved to be a sickly child and fell seriously ill with the diarrhoea that killed a third of all newborn babies. He was saved by the local doctor. When Marie suggested that baptism would protect little Serge, Paul scoffed at the idea and told her to pay for proper treatment and medicine. Her reluctance to do so, which Paul construed as penny-pinching, was a cause of friction between them. Paul also knew that other men’s wives had deceived them and feared Marie would do likewise; she was afraid that Paul, who had more opportunities, would be unfaithful. Sexual frustration loomed large in their lives and they always hoped that Paul’s leaves would not coincide with the time of the month when ‘Aunt Rose’ came to visit.

Their correspondence is, as Hanna says, a love story. But she also sees them as a representative couple whose private lives yield public lessons. Marie felt cut off and Paul sympathised with the mutineers of 1917. But the inhabitants of Nanteuil-de-Bourzac were no more ignorant of the horrors of the war than the rest of the population, nor was Paul overcome by feelings of alienation. Both home and Western fronts kept going not because the French believed in the union sacrée or were perpetually pumped up by their leaders (such things go unmentioned in these letters) but because of improved material conditions and because the civil and military administration maintained morale and the momentum of the war effort. To be sure, there were antimilitarists, soldiers who kept their heads down, civilians who claimed allowances to which they weren’t entitled and much selfish behaviour. But overall the sense of nationhood was too strong to entertain the thought that France would be defeated and turned into a second-class power.

These letters also demonstrate that life in towns was not as easy as many country people believed, and country life tougher than city-dwellers were prepared to concede. But most of all, Hanna is struck by the way Marie and Paul reflect the modernising impact of the war on the rural psyche. As a couple, they remained conservative enough to fear the effects of the rise in the divorce rate and marital infidelity generally. But they grew markedly less religious, more politically aware, less suspicious of the urban point of view and more deeply French. Paul had met Bretons and Provençaux and learned that patriotism was the sum of many local patriotisms, all as strong as his own. His generation rejected local lore, local culture and the old superstitious ways, and embraced science and the modern world and information found in books. The practice of writing letters stimulated self-reflection and self-awareness and left both husband and wife better able to communicate with each other. The postwar transformation of rural France was made possible by this enforced wartime correspondence course in self-discovery.

Paul returned to Nanteuil in July 1919 and lived there until his death in 1970. He welcomed the arrival of electricity in the 1930s, helped to repair the church despite his anticlericalism, saved a priest from vigilante justice during the Second World War and was the commune’s mayor in the 1950s. Hanna doesn’t say whether he joined any of the postwar pilgrimages to Verdun, or visited the ossuaire inaugurated in 1932, or the memorial opened in 1967. Marie died in 1978, five years after their son, Serge.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.