I could have taken the train into Rome and gone to an English-language bookshop – there’s even one at the railway station – to buy a copy of Michael Crichton’s new novel, Next (HarperCollins, £17.99). But why go to the trouble of spending the whole of Wednesday morning buying a book, when I could just download it now, on Tuesday evening?

Diesel eBooks were offering Next in three formats: I plumped for the Adobe version, since I had Adobe Reader 7, which appeared to exceed the advertised minimum software requirements. So I tapped in my credit card details (only $16! So cheap!), waited for the confirmation email, and went to download the book – at which point a message popped up telling me that a critical component was missing from my Adobe Reader, and that I should ‘click here’ to download the necessary updates. So I clicked there. Another message popped up telling me that no updates were available. I supposed I’d just have to download Adobe Reader 8. The file is bigger than 20 megabytes; I don’t have broadband. It would be quicker to walk to Rome.

So on Wednesday morning I took my laptop down to an internet café, handed over my driving licence for photocopying, as required by a nonsensical piece of anti-terrorist legislation, paid for an hour’s surfing – and found that the wireless network wasn’t working. Fortunately, a shop along the street that sells long-distance phone calls, broadband internet access and carpets let me plug my machine into their network (once they’d photocopied my driving licence). Surely, now, the thrills that only a novel by Michael Crichton can provide were mere seconds away. Inexplicably, however, Adobe Reader 8 stubbornly refused to download. So I resigned myself to acquiring Microsoft Reader instead, and forking out for another copy of the novel in a different format.

Microsoft Reader is a mere 3.5 megabytes. It downloaded very quickly. But I had to ‘activate’ it before it would work. You can only ‘activate’ it using Microsoft’s Internet Explorer: other web browsers, such as Mozilla Firefox (which the new Internet Explorer 7 appears to have borrowed most of its good ideas from), won’t do. Worse, you can only activate Microsoft Reader if you have a Microsoft ‘passport’: basically, a Hotmail address which allows Microsoft to keep track of who’s using which of its products. So I signed up under the name Bill Gates. BillFuckingGates@hotmail.com wasn’t allowed, disappointingly, because it contained an inappropriate word. BillTosserGates got through, though: please feel free to send emails with large attachments to that address and clog up its inbox until it expires through disuse in a month’s time.

Once I’d activated my Microsoft Reader, I went back to Diesel eBooks and bought another copy of Next in Microsoft format. And then, just as my credit card payment went through, Adobe Reader 8 started spontaneously downloading. I was fully primed for a science fiction novel about the menace of evil corporations and their malicious technology.

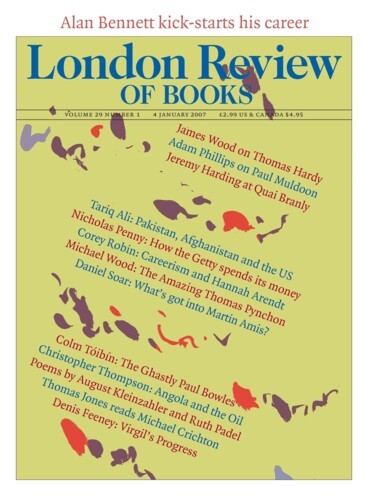

Twenty-four hours later – including a few breaks to indulge in such Luddite activities as eating, sleeping, going to the market and reading the last issue of the LRB – I’d burned through the 400-odd pages of Next, plus the exclusive eBook extras (a couple of interviews; an article Crichton wrote for the New York Times last March), and my eyes hurt. Strange shapes in many colours swirled across my vision when I looked away from the screen. I’ve only read one of the sodding things, but that’s more than enough to convince me that ebooks suck. Especially if they’re written by Michael Crichton.

Crichton’s previous effort, State of Fear, which is available in Italian and hardback at my local post office, turns on the premise that climate change is a load of hooey cooked up by ecoterrorists for their own nefarious purposes. It was very popular with, among others, the Bush administration. Crichton was summoned to the White House, and asked to testify at Senate committee hearings. As Michael Crowley pointed out in the New Republic, Crichton was in a paradoxical situation: he’s made a career out of telling stories about so-called scientific experts royally fucking things up for ordinary people, from The Andromeda Strain (1969), in which a US government satellite crashes to earth, bringing with it a deadly alien microscopic organism, to Jurassic Park (1990), in which dinosaurs are genetically engineered from a blood sample discovered in a prehistoric mosquito trapped in amber (no, it’s not possible); and now he found himself taking on the role of one of the experts he so despises, if in a strictly amateur capacity. Crichton can’t have been very happy with Crowley’s piece about him: there’s a character in Next called Mick Crowley – ‘a Washington-based political columnist’ – who’s being prosecuted for raping a two-year-old boy. Somewhat implausibly, public opinion, skilfully manipulated by Crowley’s legal team, is on the side of the plaintiff.

Crowley’s not the only paedophile in the story: Brad Gordon is a security guard at a Californian biotech firm, BioGen Research Inc. He’s terrible at his job, but gets to keep it because his uncle, Jack Watson, is the firm’s principal shareholder. Brad spends his free time watching 11-year-old girls play soccer.

BioGen, in league with the corrupt professors at UCLA, owns a cell line derived from tissues taken from an ex-marine called Frank Burnet. Burnet’s cells are potentially valuable because they’re abnormally good at producing cytokines, proteins with anti-carcinogenic properties. Burnet is trying to sue UCLA for removing his tissues under false pretences and exploiting them for commercial gain.

Rick Diehl, the CEO of BioGen, wants a divorce, and plans to get custody of his children by showing that his wife has a genetic predisposition to ‘bipolar illness’, Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s chorea which makes her unfit to be a mother. He’s prepared to fake the lab results to get his way.

Josh Winkler, a junior BioGen scientist, has to leave the lab in a hurry one day to collect his brother from jail. His brother, who’ll do anything to get high, inhales a dose of a retrovirus – the device that administers it falls out of the pocket of Josh’s labcoat in the car – that contains a gene that causes young rats to behave like old rats. It’s not long before Adam Winkler is off the drugs and going to work like a proper grown-up. But he also starts going grey and walking with a stoop.

Meanwhile, an orangutan in Sumatra is swearing at tourists in several European languages, an African Grey parrot is helping a small boy in Paris with his maths homework, and a chimpanzee at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland is asking people in English where and who his mother is. And that’s all just for starters.

Next is populated by a bewildering horde of dislikeable and indistinguishable characters. Everyone is selfish, greedy, treacherous, murderous and – least forgivable – humourless. When planning the book, Crichton has said, he ‘was unable to overlook the structure of the genome . . . and how individual genes interact with other genes, or may seem to be silent, or we don’t really know what they do, or sometimes there are repetitions that are not clear to us, and it struck me as an interesting idea to try to organise the novel in that way’. The result is a confused mess, which may be an accurate reflection of our current understanding of the way genes work, but isn’t a very good way to structure a novel.

Crichton has a definite polemical aim. He must have been worried it wasn’t made clear enough in the story – though there’s really no need for such concern – because his ‘author’s note’ is a list of instructions to the US government: ‘stop patenting genes’; ‘establish clear guidelines for the use of human tissues’; ‘pass laws to ensure that data about gene testing is made public’; ‘avoid bans on research’; and ‘rescind the Bayh-Dole Act’, which allows university researchers to profit commercially from their work. These are interventions in a fraught and complex debate which I don’t feel qualified, even after reading Crichton’s novel, to take a strong position on.

I do think, however, that using fiction as a blunt didactic tool does no favours either to the medium or to the message. On the one hand, a good novel about biotechnology would stage subtle dramatisations of the debate’s contradictions and ambiguities, encourage readers to sympathise simultaneously with characters who disagree with each other, and generally be more interested in complicating the questions than in pronouncing on the answers. Those are fiction’s strengths, though Crichton, who has described Henry James as ‘trivial’, would no doubt disagree.

On the other hand, an informed argument about the benefits and dangers of new kinds of scientific research and the ways they should be funded and controlled isn’t helped by an unintentionally hilarious emulsion of bombast and bathos in which cynical financiers explain how they run the world while transgenic hybrid children, half-chimp, half-human, climb chainlink fences and throw shit at mean older kids.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.