4 January, Yorkshire. A heron fishes by the bridge as I walk down to get the papers this morning, but when I draw nearer it takes off and flaps up the beck. Not a rare bird, the heron’s size is never less than spectacular, and grey and white though they are they still seem exotic.

Bitterly cold with snow forecast later so we get off early up the M6 to Penrith and Brampton, hoping to have a look at the Written Rock, a quarry by the river at Brampton with an inscription carved by the legion that cut the stone here for nearby Hadrian’s Wall. But it’s too cold to go looking for it and it’s said to be overgrown and eroded now, but somehow to see the place that supplied the stone and the mark the men made who quarried it seems much more evocative than the actual wall itself. Instead we buy a couple of George III country chairs very reasonably in an antique shop before going round the much larger antique centre in Philip Webb’s parish hall.

6 January. Papers full of Charles Kennedy being, or having been, an alcoholic. I’d have thought Churchill came close and Asquith, too, and when it comes to politics it’s hardly a disabling disease. Except to the press. But less perilous, I would have thought, to have a leader intoxicated with whisky than one like Blair, intoxicated with himself.

17 January. At the Annual General Meeting of the Friends of the British Library I read (rather haltingly) a piece I’ve written about the libraries I’ve worked in, including the Round Reading Room at the old Public Record Office in Chancery Lane. The memoranda rolls on which I spent most of my time were long, thin swatches of parchment about five foot in length and written on both sides. To turn the page required the co-operation and forbearance of most of the other readers at the table, so it would sometimes look like the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party struggling to put up wallpaper when all I was doing was trying to turn over.

A side effect of reading these unwieldy documents was that one was straightaway propelled into quite an intimate relationship with the readers alongside, and one of those I got to know in this way was the historian Cecil Woodham-Smith. The author of The Great Hunger, an account of the Irish famine, and The Reason Why, about the events leading up to the Charge of the Light Brigade, Cecil was a frail woman with a tiny birdlike skull, looking more like Elizabeth I (in later life) than Edith Sitwell ever did (and minus her sheet metal earrings). Irish, she had a Firbankian wit and a lovely turn of phrase, ‘Do you know the Atlantic at all?’ she once asked me, and I put the line into Habeas Corpus and got a big laugh on it. From a grand Irish family she was quite snobbish and talking of someone she said: ‘Then he married a Mitford … but that’s a stage everybody goes through.’ Even the most ordinary remark would be given her own particular twist, and she could be quite camp. Conversation had once turned, as conversation will, to forklift trucks. Feeling that industrial machinery might be remote from Cecil’s sphere of interest I said: ‘Do you know what a forklift truck is?’ She looked at me. ‘I do. To my cost.’

20 February. One of the pleasures of painting, even if it’s only the wall which I’m currently engaged on, is to be able to visit Cornelissen’s shop in Great Russell Street, which sells all manner of paints and colours and where I go this morning in order to find some varnish to seal the surface of the plaster.

After I’d finished putting on all the greenish-yellow colour yesterday I did some trial patches of varnish on it. I knew, though it’s twenty years since I last stained a wall, how this transforms and enlivens the colour but I am astonished all over again at the depth and interest it gives to even the most ordinary surface. There’s no literary equivalent that I can think of to this vernissage, no final gloss to be put on a novel, say, or a play which will bring them suddenly to life. Today when I go down to Cornelissen the assistant suggests that as an alternative to the gloss I try shellac, which has even more of a surface. It’s one of the pleasures of the shop that you’re served by people who know what they’re talking about and who, one gets the feeling, go home from work, don a smock and beret and go to the easel themselves. Which reminds me how when I first stained some walls, back in 1968, I had no need to come all the way down to Cornelissen. Then I just went round the corner in Camden Town where Roberson’s had a (long gone) shop in Parkway. They were old established colourists and had in the window a palette board used by Joshua Reynolds. Whatever happened to that?

Further to the painting, though, for which I scorn to don the Marigolds, I am buying bread in Villandry when I see the assistant gazing in horror at my hands, the fingers stained the virulent yellowish green I’ve been sponging on during this last week. As a young man my father smoked quite heavily and his fingers were stained like this by cigarettes – and a nice brown it was, and one which I wouldn’t mind seeing on the wall; if he were alive still and the man he was when I was ten I could take him along to Cornelissen where I’m sure they could match his fingers in water, oil or acrylic.

And it stirs another memory from the 1970s, or whenever it was that the IRA conducted their ‘dirty protests’ at the Maze prison, smearing the walls of their cells with excrement. Occasionally one would see edited shots of these cells on television when I was invariably struck by what a nice warm and varied shade the protester had achieved. ‘Maze brown’ I suppose Farrow and Ball would tastefully have called it.

4 March. We stay the night at Lacock, as R. is doing a shoot at nearby Corsham Court. In the morning we walk round this picture-book village wholly owned by the National Trust since 1944. It’s not yet ten o’clock but there are already cars in the car park and visitors strolling about; the bells are ringing for matins and, mingling with the visitors, a family, prayer books in hand, makes its way to church. Except is it a family, or is it like everything else in the village a dependency of the National Trust? It’s not that the place is manicured particularly, though there is no stone out of place, just that its beauty and its settled tranquillity are in themselves slightly sinister.

15 March. After the murder of Mr de Menezes Tony Blair claimed that he ‘entirely understood’ the feelings of the young man’s parents. Today it is the 80,000 people who, following the government’s urgings, subscribed to their employers’ private pension schemes. When the firms went bust or were unable to pay, their workers unsurprisingly turned to the government to make good their lost annuities, except that now the government claims it’s not its responsibility. However in the Commons today Mr Blair reassures the aggrieved 80,000, telling them that he entirely understands their indignation. Is there any limit, one wonders, to the entire understanding of Mr Blair? Heaped naked in a pile on the floor of an Iraqi prison it must be comforting to know that you have the entire understanding of Mr Blair. Hooded, shackled and flown 14 hours at a time across continents do you reside in the entirety of Mr Blair’s understanding? No, presumably, because of course this does not happen.

18 April. To New York for the opening of The History Boys. The plane is not full and unexpectedly comfortable but I miss the now archaic ritual of transatlantic flights in the days before videos and iPods: the coffee and pastries when you got on, the drinks and the lunch before the blinds went down and they showed a film. Once that was over you were already above New England and there was tea and an hour later New York. Now there’s no structure to it at all, just choice – choice of programme, choice of video and no tea either, just today, a choice of pizza or a hot turkey sandwich. I browse through Duff Cooper’s diaries dosed up on valium.

An odd incident at Heathrow. There is a long queue to go through security and a boy of eighteen or so comes down the line asking if he can go to the front as his plane takes off in twenty minutes. This he’s allowed to do, my own flight not due to go for well over an hour. I am among the first off at JFK when I see this youth again, now hurrying to be ahead in the immigration queue also, so his claim to be on an imminent flight must have been a lie, and had anyone else spotted him who had previously let him through there might have been words spoken. Just in T-shirt and jeans he doesn’t look as if he’s been in First or Business so he must have parlayed his way off the plane ahead of everyone else just as he did earlier. But he has luggage and there is no avoiding that, and as I spot my name on a card and see a driver waiting he is still hanging about restlessly at the carousel. Disturbing, though, and it leaves me wanting an explanation and a notion of his life.

21 April. Persisting with the Duff Cooper diaries, which, though they’re more than frank about his innumerable liaisons, are utterly silent on more interesting topics, the cruise of the Nahlin, for instance, in 1936 when Duff Cooper and his wife accompanied the King and Mrs Simpson around the Mediterranean. Years ago Russell Harty had supper with Diana Cooper and she told him that she and her husband had had the adjoining cabin to the royal couple (or rather one royal, the other not) and that she had had her ear pressed to the wall half the night to see if there was any action, but heard not a thing. The other guest at supper was Martha Gellhorn, both of them getting on and quite pissed, so that Russell spent the meal rushing from one end of the table to the other as each in turn slowly toppled off her chair.

Duff Cooper’s philanderings are often quite funny. Having rekindled an old flame, Lady Warrender, he adjourns with her to his Gower Street house, now emptied of furniture and up for sale. Suddenly, while they’re at it, there’s a loud banging on the door downstairs which Duff Cooper eventually has to answer and it’s the estate agent with some prospective buyers wanting to see the house. It’s made funnier (and rather Buñuelesque) by Duff C. and Lady W. being so middle-aged and ultra respectable. John Julius Norwich puts his father’s sexual success down to his ability to write bad sonnets to his lady-friends but one wonders if it was a more basic attraction. The moustache is hardly a plus, the photograph on the book jacket making him look like a 1940s cinema manager.

22 April. I do the rounds of the TV and radio arts programmes prior to the opening of the play on Sunday, accompanied by Jim Bik, our young low-key PR man. At one venue we are met in the lobby of some huge new communications emporium by the TV call boy who takes us through various gleaming and coded doors until we get to one where the code he punches in doesn’t work. Not, I think, making a joke he says apologetically, ‘Guess this is kind of lo-tech,’ and knocks on the door.

23 April. The theatre where The History Boys is playing, the Broadhurst, is as dull as New York theatres mostly are, painted battleship grey and on this opening night packed with a slow-moving crowd of playgoers reluctant to take their seats. Beforehand, we go round and see the boys, who are a bit excited, though it’s not a first night on which much depends as most of the critics have already been during the previews. The play itself seems to me to go too quickly and is a bit slurred, the result not so much of it being a first night as that the cast have been doing it on and off now for two years. When James C. drops his head on his desk it’s with an almighty crash and he gets up looking a bit pale, but there are no other slip-ups. The response at the end is tumultuous, the audience (though I think this is nowadays obligatory) rising to their feet en masse. We go round backstage to find them all getting ready for the party; some of them have allowed themselves to be styled for the occasion in suits and big plain-coloured Windsor knotted ties so that they look more like footballers than actors.

Then to the Tavern on the Green, a stupendously vulgar venue where we have to proceed past a gallery of photographers and TV cameras. Whether this is what always happens to a greater or lesser degree I’m not sure but there’s not much doubt it’s been a success, proved apparently by the readiness of the guests to remain at the party. I scarcely eat simply because I have to keep getting up to greet the boys’ parents and, in Sacha Dhawan’s case, his sisters and his cousins and his aunts, who have followed the production across the world through Hong Kong, New Zealand and Australia to this first night on Broadway. Back at 16th Street by 11.30 happy that it’s all done with.

25 April. En route for Boston by train Lynn W. has booked us onto the quiet coach, which is where we often sit when going up to Leeds. It isn’t always quiet, though, and in my experience is probably the most contentious coach on the train. This is because, in England at any rate, the prohibition against the use of mobile phones is often ignored or not even acknowledged so that the occasional bold spirit will then protest and a row breaks out, and even when it doesn’t there’s often some unspoken resentment against offenders, who are often unaware.

This morning our coach is quite subdued, no one uses a mobile, though the three of us talk quietly and occasionally Lynn laughs. I notice one or two stern heads bobbing above the seats without realising why until one pale, wild-eyed Madame Defarge-like figure advances down the carriage and gestures mutely at the Quiet Coach notice. We stop talking (though find it hard not to giggle). However another couple, possibly German, not realising they are committing an offence continue to chat whereupon Madame Defarge confronts them, too, and then goes in search of the conductor. As she passes me I say, mildly: ‘It’s only a quiet coach. It isn’t a Trappist one.’

‘Yes, it is,’ she snaps and returns a few minutes later with the conductor who gives the new offenders a mild lecture. I pass Madame Defarge again as I tiptoe down to the loo and see she’s working on some sort of thesis, her ideal mode of transport I suppose a cork-lined carriage. The ‘Marcel Proust’ might be a good name for a train.

16 May. Philip Roth’s face in a photograph by Nancy Crampton on the jacket of his new novel, Everyman, is as stern and ungiving as a self-portrait by Rembrandt.

30 May, Yorkshire. Not one in fifty people knows how to restore or convert a house. A familiar fault round here is to strip off the stucco to reveal the supposed beauty of the stonework, which is often not beautiful at all and which, badly pointed as it then invariably is, becomes a garish patchwork besides letting in more damp than it did before. We pass such a house in Lawkland today, a tall dignified place it’s always been, plain and rather Scottish-looking. Now, stripped of its weathered stucco it sports a suburban front door from a cheap builders’ merchants, and coming round the corner and seeing it transformed I involuntarily cry out. But it’s just one of hundreds in the neighbourhood to be similarly vandalised, the suburbanisation of Craven much worse than anything that has yet happened in Swaledale or Wensleydale. There’s scarcely a barn within reach of the road that hasn’t been kitted out with brown-framed windows and a little bit of Leeds or Bradford installed on its greenfield site.

1 June. Gilly P. who comes on a Wednesday evening to do our reflexology also looks after various disabled people, including Jim, who was blind and has just died. She went to his funeral at Kensal Green on Saturday where the chapel was full of guide dogs, crouched in the pews or lying in the aisle, Jim’s dog one of the congregation, too, though as ever not paying much attention, always looking round and never concentrating. It was quite absent-minded with Jim, so that he often got black eyes through bumping into things, this negligence Gilly thinks to be put down to the fact that these days there are fewer training centres for blind dogs and they’re not schooled as well as they once were.

After the service there is a wake in a local pub where many of the blind get quite drunk, blind drunk in this case not just a phrase. Several of them try tipsily to touch G. up and when she tells one of them off for groping her he says plaintively: ‘But I can’t see what I’m doing, can I?’ According to G. this is a regular get-out.

11 June, New York. Back for the second time in six weeks to Lynn W.’s 16th Street apartment, which is the penthouse of a small 1930s skyscraper with a balcony all the way round and views uptown to the Chrysler Building and Central Park and to the west the Hudson and the Jersey shore. It’s warm and windy and sitting in the bedroom with the door open I can see the Empire State Building reflected in the mirror opposite. Planes cross the blue sky unheeded as once before they did and to someone here as seldom as I am never without fell implications. We have a long brunch at the Odeon then walk back to 16th Street to prepare for the Tonys this evening.

The cast have all been styled for the occasion but nobody has taken on the challenge of styling me, my major contribution to fashion an Armani suit and a red spotted bow tie which, though it’s tied and retied several times in the course of the evening, never manages to achieve the horizontal. It’s also a magnet for well-wishers, beginning with the doorman at Radio City Music Hall who opens the limo door and then adjusts my tie and it’s still happening five weary hours later when we come away.

In the event of our winning the best play award we had agreed beforehand that the boys should all come up to receive it, which indeed they do. But so also do a collection of people whom I’ve never seen before, and in such numbers that David Hyde Pierce, who is presenting it, is practically elbowed out of the way. These turn out to be the backers who, of course, have every reason to be pleased and indeed one of them duly adjusts my tie.

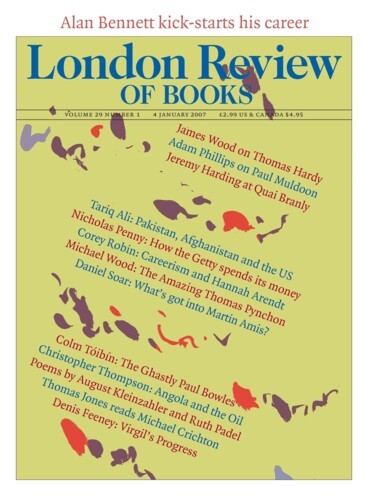

I am then bundled out through a back door and across the street to Rockefeller Plaza where a whole floor has been given over to the press. I’m thrust blinking onto a stage facing a battery of lights while questions come out of the darkness, the best of which is: ‘Do you think this award will kick-start your career?’ News of my lacklustre performance on this podium must have got round quickly because I’m then taken down a long corridor off which various TV and radio shows have mikes and cameras and there is more humiliation. ‘Do you want him?’ asks the PA at each doorway, the answer more often than not being ‘Nah,’ so I only score about four brief interviews before I’m pushed through another door and find I’m suddenly back in the street in the rain and it’s all more or less over.

16 June. Having seen the TV programme on which it was based I’ve been reading Britten’s Children by John Bridcut. Glamorous though he must have been and a superb teacher, I find Britten a difficult man to like. He had his favourites, children and adults, but both Britten and Pears were notorious for cutting people out of their lives (Eric Crozier is mentioned here, and Charles Mackerras), friends and acquaintances suddenly turned into living corpses if they overstepped the mark. A joke would do it and though Britten seems to have had plenty of childish jokes with his boy singers, his sense of humour isn’t much in evidence elsewhere. And it was not merely adults that were cut off. A boy whose voice suddenly broke could find himself no longer invited to the Red House or part of the group – a fate which the boys Bridcut quotes here seem to have taken philosophically but which would seem potentially far more damaging to a child’s psychology than too much attention. One thinks, too, of the boys who were not part of the charmed circle. There were presumably fat boys and ugly boys or just plain dull boys who could, nevertheless, sing like angels. What of them?

I never met or saw Britten, though he and Peter Pears came disastrously to Beyond the Fringe sometime in 1961. Included in the programme was a parody of Britten written by Dudley Moore, in which he sang and accompanied himself in ‘Little Miss Muffet’ done in a Pears and Britten-like way. I’m not sure that this in itself would have caused offence: it shouldn’t have as, like all successful parodies, there was a good deal of affection in it and it was funny in its own right. But Dudley (who may have known them slightly and certainly had met them) unthinkingly entitled the piece ‘Little Miss Britten’. Now Dudley was not malicious nor had he any reason to mock their homosexuality, of which indeed he may have been unaware (I don’t think I knew of it at the time). But with the offending title printed in the programme, they were reported to be deeply upset and Dudley went into outer darkness as probably did the rest of us.

24 June. Today is the last day of the British Museum Michelangelo exhibition, which, because of demand, is open until midnight. For all we go quite late, it’s still crowded out, paintings hard enough to look at under such circumstances and drawings well-nigh impossible. One straightaway abandons any attempt to look at them in sequence (not that the sequence helps) and makes for any drawing that is not being looked at, the people with earphones the real menace as they all move at the same speed and cause the jams.

More mystified than I usually am at exhibitions I can never take in the finer points of drawing and the bulging thighs and backs pebbled with muscle soon pall. R. notes, though, that women (who far outnumber men) seem to find them both moving and satisfying whereas I find them neither. Of course, Michelangelo is a star and so whatever he does is acclaimed, from the anatomical exactitude of the preliminary drawings for the Sistine ceiling through to the blurred and almost impressionistic figures of the three late Crucifixions with which the exhibition ends. It’s hard not to think that there is an element of the sacred in everything to which he put his hand: it must be reverenced because this is by the hand of Michelangelo.

A propos the hand, the most famous image is, I suppose, that of God giving life to Adam but the only (easily overlooked) drawing for this is low down on a sheet of other drawings. There is a line drawn round the fragment, as at one stage it was cut out of the sheet before being later reinstated, but it’s so formal that there is little remarkable about it and it’s not unlike the stylised 18th-century hand on the signpost on Elslack Moor.

I wonder, looking at all these thighs and torsos, the dicks never closely anatomised, whether Michelangelo ever did any pornographic drawings, as all artists must at some time be tempted to do, and if so what happened to them. I wonder, too, if they had survived and were exhibited here, a couple unabashedly making love, for instance, a boy getting it on, whether these would attract this same Saturday night crowd who would subject the sacred porn to their wholesome, safe, art-loving scrutiny, making them just as hygienic as the rest.

1 July. Watch the commentary and round-ups (they could hardly be called highlights) after the England-Portugal match. One Shakespearean moment at the start when Cristiano Ronaldo comes up behind his Manchester team-mate Rooney and nuzzles him, saying something that seems to be kind but almost certainly isn’t as Rooney then swings round to watch him go. It’s like an impossibly beautiful Iago goading a simple lumbering Othello, an impression confirmed when, after Othello gets the red card, Ronaldo comes away with a tranquil smile.

2 July, Yorkshire. Two rather dull fawny-coloured birds are nesting in the creeper just outside the kitchen door. Watching them (and looking them up in the bird book) I find they are fly catchers, one keeping station on the garden wall then looping round over the lawn until it collects a packet of insects in its beak which it takes back to the nest thereby releasing its mate to do the same. They winter in Africa and summer here in Craven, a circumstance I find – what? – both pleasing and, in some undefinable way, encouraging.

Working in the garden we are watched in the heat by the toad, which is just a slight bump in the water in the corner of the trough, its eyes on a level with the surface taking in the proceedings, then when the garden gets too mouvementé he/she turns its back and stares instead at the less taxing wall.

5 July. Last week I met David Walliams in Melrose and Morgan, our new posh local delicatessen. Big, handsome in a slightly Tartar way, he and Matt Lucas must currently be the most famous people in the country. Today he swims the Channel, seemingly without much effort and with very little ballyhoo. When I was a boy a young swimmer from Leeds, Philip Mickman, swam the Channel and the preparations and the weather and the pictures of him plastered in grease were front-page news in the Yorkshire Evening Post for weeks beforehand. Now, like Everest, people do it all the time, no problem.

8 July, Yorkshire. As I’m getting some money out of the cashpoint on Duke Street in Settle I feel a tug at my jacket. I look down and it’s little white-haired 85-year-old Onyx Ralph, who just about comes up to my waist. ‘Hello, Mr Bennett. Did you think I was a mugger?’

11 July. Baroness Scotland is put up to defend the government’s shameful capitulation to the United States in the extradition treaty. She makes much of the rule of law in America and the independence of the Supreme Court, citing its stand (after four glorious years) on Guantanamo but says nothing of the next person likely to be extradited, the hacker who got into the Pentagon computer. Whereas the three NatWest bankers can at least afford some defence, what will the next victim be able to afford? Nor does Baroness Scotland say anything of the plea bargaining that goes on in the US’s nobly independent courts where the US accused cut their own sentences by putting the blame on their foreign associates who are then shipped across the Atlantic in shackles. The World at One gives the baroness an easy time as does Joshua Rozenberg, both blandly dismissive of this diminution of the subject’s rights. The plain fact is that to be extradited on a charge the evidence for which has not been heard before an English court, is unjust.

16 July. Palmers, the old-fashioned pet shop in Parkway, which has been there as long as I can remember and from the look of the place much longer than that, has now closed down. The signs on the shopfront (which I hope Camden Council has had the sense to list) read: ‘Monkeys. Talking Parrots. Regent Pet Stores. Naturalists.’

In 1966 Patrick Garland and I filmed some poems to include in a comedy series we were doing, On the Margin. The standard form of comedy sketch shows then demanded a musical interlude between items, Kathy Kirby, say, or Millicent Martin. Boldly (as we thought) we opted for poems instead and were considered very eccentric, but Frank Muir, then head of comedy, and David Attenborough, the controller of BBC2, said it was all right and so we filmed Palmers to illustrate Larkin’s poem, ‘Take One Home for the Kiddies’. Another of his poems we used was ‘At Grass’. Whether Larkin cared for either I don’t think we ever heard.

I walk by today and in the window of this empty pet shop is a sad bedraggled pigeon, not, one imagines, a remnant of the stock but which must have got in through the already decaying roof and which sits there now, forlornly on offer. It’s another poem.

17 July. The Met is to be prosecuted for ‘failing to provide for the health, safety and welfare’ of Mr de Menezes. Naive, I suppose, to have thought that the police would be brought to book for the shooting. They never have been in the past so why now? The longer and more protracted the investigation the plainer this has become, the boredom of the public now presumably part of the strategy. The truth is that on the relatively few occasions that the police kill they do so with impunity. The only reason this is not enshrined in law is that if it was they would do it more often. Still, if the police were authorised to shoot to kill it would at least make the law ‘fit for purpose’, in the home secretary’s noxious phrase, and so gladden his heart. Meanwhile,one wonders what has happened to the policeman who did the actual shooting. It’s to be hoped he’s not still out there defending our liberties.

(1 November. It turns out that he is and in exactly the same way, though cutting down at least on the number of shots, seven in the case of de Menezes, one in yesterday’s shooting. Presumably his strike rate has improved as a result of the ‘retraining’ he has received and, of course, the counselling.)

One criterion for judging this (or any other) government is how often it makes one feel ashamed to be English. Today ratchets up the score. I don’t think it’s quite up to Thatcher’s level but it’s getting there.

22 July, Yorkshire. The village street market is all set up by nine thirty, the cake stalls, the jam, the tombola, the duck race and (R.’s target) the junk stall, on which he has spotted a very run-down Ernest Race Festival of Britain chair which, as soon as the market is declared open (by the ringing of the church bell), he buys for £1. Pretty battered and minus its ball feet it’s still got the original wooden seat, and is one of many thousands of such chairs that were scattered throughout the Festival of Britain on the South Bank that summer of 1951.

We also buy an almond madeira cake and some delicious raspberry jam, the cake and the jam stall always the first to sell out. When events like this are depicted on television (e.g. in Midsomer Murders or Rosemary and Thyme) it’s always as occasions for vicious backbiting and murderous (literally) rivalries. There’s none of that here, I’m happy to say. Everybody speaks and the topography of the village, a long straight street backing onto the beck, is ideally suited to the row of stalls. The chair is taken through into the garden where R. spends the rest of the day restoring it.

24 July. A card from a friend in New York prompted by the invasion of Lebanon.

‘Please go to the US Embassy and throw stones. S.

(Say I sent you.)’

30 July. Tony Blair addresses Rupert Murdoch’s conference of newspaper editors and tells them that there is now no more left and right. In view of his audience he would have done better to tell them there is no more good and evil.

5 August, L’Espiessac. Installed contentedly in the Pigeonnier Est, utterly silent, the tall windows filled with the bluest of skies and with a soft breeze that stirs the sheet as I write. On the mantelpiece Lynn has put a large schoolroom-size bottle of Waterman’s Ink in its original, unopened box, the lettering and the design of the box putting it in the early 1950s, just after the Festival of Britain. The logo is in the shape of a television screen, which was the coming thing in 1952, the box, I suppose, meriting a place in the Design Museum.

I am reading The Man who Went into the West: The Life of R.S. Thomas by Byron Rogers, whose book on J.L. Carr I read here on holiday last year. R.S. Thomas, the poetry of whom I scarcely know, sounds as bleak as Larkin pretended to be.

A huge hawk hovers high above the house. It doesn’t fly off but just drifts upwards, and is gone. A hawk can hide in an unclouded sky.

10 August, Toulouse. An unexpected queue for the 10.30 BA flight, the only clue a leaflet being handed out, saying that no hand baggage is allowed and all belongings must go in the hold. Everyone begins to repack their bags, which we would be happy to do, except that our hand baggage includes the aforesaid bottle of Waterman’s Ink. This can hardly be put in the hold lest it break, inundating not only our luggage but everybody else’s. When we reach the check-in we explain this to the harassed woman, who eventually caves in, partly helped by consulting our details on the computer. More impressed by my status than anyone else, my travel agent always gets VIP put on my ticket. ‘Pourquoi,’ they say at the check-in, ‘vous êtes VIP?’

‘Je suis un écrivain.’ It’s a statement I’m readier to make in French than in English, but it causes hysteria among the check-in girls.

‘Ah, oui. L’encre!’ and then everyone goes into peals of laughter.

‘Non, non,’ I say lamely. ‘C’est un cadeau excentrique.’ More hysteria and on the strength of it we are waved through. It’s only when we get to Gatwick (which is about to be closed) that we find that the ‘plot’, such as it is, centres on suspect liquids. Presumably nobody at Toulouse yet knew this and the sniffer dogs at Gatwick don’t seem to know it either, as not being ink-sensitive they twice turn their noses up at our bags.

14 August. A year or two ago the National Parks were complaining that their visitors were predominantly white and that the Asian population of Leeds and Bradford, for instance, left them largely unvisited. In this morning’s Guardian it’s claimed that would-be terrorists learned some of their skills in camps in national parks in the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales. So some improvement there.

24 August. I am reading The Secret Life of Cows by Rosamund Young, a delightful book though insofar as it reveals that cows (and sheep and even hens) have far more awareness and know-how than they are given credit for it could also be thought deeply depressing. Though not if you’re a cow on Young’s farm, Kites’ Nest in Worcestershire, which has been organic since before organics started and where the farm hands can tell from the taste alone which cow the milk comes from. Young makes the case against factory farming more simply and compellingly than anyone I’ve read and simply on grounds of common sense.

One curiosity about the book, though, is that while the author goes into much detail about the behaviour of cows and their differences of temperament and outlook she never mentions any idiosyncrasies when the cows go with the bull and whether their individuality, which she has made much of elsewhere, is still in evidence. Are some shyer than others? More flirty? It may be of course that this reticence is a measure of her respect for her charges, feeling that cows are entitled to their privacy as much as their keepers. But it’s a book that alters the way one looks at the world and one which all farmers would do well to read.

2 September. Making the supper and idly listening to Radio 4’s Saturday Review the only speaker I recognise is P.D. James and none of it anything to do with me until some Scottish woman in the course of telling off the novelist Mark Haddon accuses him of ‘Alan Bennettish tweeness’. It’s not a serious injury to my self-esteem but rather as if someone passing me in the street has just turned back to give me a flying kick up the bum and then gone on their way. I hope for some mild objection from one of the other participants but none is forthcoming so perhaps I’m now tweeness’s accepted measure.

28 September. At the outset of the Iraq war Tony Blair was determined not to be another Chamberlain. Now as he slowly prepares to leave office one can see that Chamberlain is exactly who he has come to resemble. In the 1930s Chamberlain put through some enlightened social legislation, but all anyone nowadays remembers is Munich and Appeasement. Tony Blair, too, has achievements in the social field but no one will remember those, only Iraq. I suppose this says something about history.

29 September. I call in at the Farmers’ Market which now takes place every Saturday in the playground of Princess Road school. It’s a friendly occasion, but whereas in Union Square in New York, the only other farmers’ market I’ve been to, I take it as simply a nice (and useful) collection of stalls – meat, veg, bread, cheese – and am unself-conscious about it, here, on my own patch as it were, I’m aware of the middle class (and it is predominantly middle class) hugging themselves in self-congratulation at the perfection of their lives. I know this is unfair and grumbling and I wish I were more open-minded and didn’t care. But as it is I queue to buy two slices of delicious looking pork pie but am put off by the vendor’s over-cheerful butcherly demeanour (and his brown bowler) and come away empty-handed.

30 September. When, passing the house, someone lights up a joint they straightaway look at the lit end, something they never do with a straight cigarette.

1 October. Watch Bremner, Bird and Fortune which nowadays we generally miss since it’s been shifted forwards to 8 o’clock. It contains a pun so terrible it ranks with those John Bird, John Fortune and I used painstakingly to construct for the (live) performances of Not So Much a Programme and the Late Show back in the 1960s.

In tonight’s programme they are talking of someone who is ‘not fit for purpose’ and JF says that this leaves out of account the hapless employee of the Brighton Dolphinarium who was recently sacked on similar grounds.

JB. I didn’t hear about that.

JF. Oh yes. Not fit for porpoise.

Back in the 1960s Bird and Fortune were playing detectives, one of whom was called Farley.

JB. It’s a risk, Farley.

JF. No. It’s a rusk, Farley.

The puns were deliberately introduced, sometimes without prior warning in order to break each other up, which in Fortune’s case was always signalled (as it still is) by his opening his eyes very wide and shaking his head, a process known as ‘boggling’. It doesn’t happen this evening but it brings back the exquisite agony of trying not to laugh in full view of two million people.

8 November. To Oxford with Bodley’s librarian emeritus, David Vaisey, to look at the muniment room in New College. It’s in the tower above the hall and chapel, with access by a spiral staircase so narrow that the two huge ten foot chests which used to house the deeds and documents must have been built in situ in the 15th century. There are also two complete medieval tiled floors. Down the road we toil up another spiral staircase to the muniment room in the Bodleian, where there is no medieval floor but a delicate early 18th-century ceiling that might have come out of Claydon House, part of the fall-out after Gibbs built the Radcliffe Camera, a building which still astonishes me now as much as it did when I was a young man.

That young man turns out to have records here, too, as Simon Bailey the archivist shows me my original October 1954 application for a reader’s ticket, my best 21-year-old handwriting making me wince even fifty years later. I have other records, too, which ought to make me wince but don’t, as here is a character assessment of me written by G.D.G. Hall, the law tutor and sub-rector of Exeter who was later president of Corpus, a document originated when I went, as everyone did at the beginning of their third year, for an interview at the University Appointments Board in order to be placed for a job. Derek Hall’s remarks on my character seem wholly fair and very perceptive: ‘amiable, funny but not a first-class mind’. He ends up, ambiguously, ‘not yet ready to play about with people’, meaning, I think, that I wasn’t fit for an appointment that carried any sort of authority. Though if there’d been more ‘playing about with people’, not just falling hopelessly in love with them, I might have been more fitted for Life back then in 1957. It’s a source for Jake Balokowsky, and, under the Freedom of Information Act, an available one, apparently.

11 November. Catch part of the Festival of Remembrance from the Albert Hall but find myself switching over less from inattention than because it’s more vulgar, sentimental and, inevitably, hypocritical than I can ever remember. The problem facing the producer is to find a way of commemorating the most recently dead without getting into the rights and wrongs of the circumstances in which the deaths occurred. If in doubt, though, he cuts to World War One and Two where we’re on safe ground. After the messy roadside bombs of Iraq it’s almost a comfort to be back among the tombstones and immaculate graves of Flanders.

Unsurprisingly there is not much room for jokes, but these days audiences need to be diverted, the Palladium and the Royal Albert Hall not all that far apart. So some elaborately dishevelled youth sings his heart out, along with another dewy-eyed group, and Chris de Burgh leads the nation in ‘Abide with Me’. It’s the Royal Sobriety Show.

As the various contingents march in and fill the arena, one longs for some representatives from Families Against the War, which would at least bring a breath of honesty to the proceedings. As always at such ceremonies, the dead don’t get a proper look-in and having made their sacrifice are now taken to be somehow on the reserve, endorsing the continuing wars of the living. Overseeing it all is the bishop of Manchester, who has the face of a rugger forward and presumably the skin to match, because the ironies of the ceremony are inescapable. No wonder the queen looks grim throughout, though as the royal party rises the one whose thoughts one would like to share is Princess Anne.

24 November, Rome. Sitting on a bench in the Pantheon while R. and Lynn fight their way round through hordes of schoolchildren (and it isn’t even half-term) I get talking to a young man who turns out to be a stonemason at Ely, working on the restoration of the cathedral. He has been redoing some of the medieval carvings and says that the higher up the carving the more lewd the carvers’ imagination. One capital he has had to restore had a devil biting off someone’s balls, and he needed the chapter’s permission before he could reproduce it. He thinks the medieval carvers enjoyed such licence because the scaffolding on which they worked was so rickety the architect or the master mason was reluctant to risk much hands-on supervision and just let them get on with it.

25 November, Rome. The last day of a Caravaggio exhibition in Santa Maria del Popolo and the queue goes right round the church. We don’t wait, but notice that the people queuing pay as much attention to the preparatory display of screens and moving images leading up to the actual paintings which, when they eventually reach them, they’re rapidly hustled past. Come away depressed but are then cheered when, turning down a side street, we pass what looks like the back of a shabby garage. Except that the walls of these seemingly industrial premises are studded with architectural fragments – bits of moulding, tracery, the broken sculpture of a head or a hand and of all periods. The supposed ‘garage’ turns out to be the onetime studio of Canova.

27 November. For the poisoning of Mr Litvinenko there is this to be said: unlike all the other plots which repeatedly hit the headlines, from this one at least Downing Street and the Home Office have nothing to gain and so one can believe it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.