The pleasures of piety are infinite and exquisite and probably nowhere more easily had these days than in the rock ’n’ roll business, or in Hollywood. On record, and on stage, and up there on the big screen, people are not only encouraged but also handsomely rewarded for being morbidly fascinated with themselves, with their every movement, their every utterance, with the tiniest flicker of an eyelid or the slightest suggestion of a thought – a self-regard and obsession with the self usually only available to religious novitiates, madmen or very young children. Fame, with all of its fleshly temptations and attendant despairs, is an obvious incitement to grace; thus, George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, and Rock Against Racism, and Live Aid, and Farm Aid, and Red Wedge, and Rock the Vote, and Live 8, Coldplay, U2, the late and the later John Lennon, and perhaps almost as many good causes as there are actors. It can only be a matter of time, surely, before Eminem turns, however briefly, to Christ and begins to walk in the way of righteousness, as Alice Cooper, Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins, Kris Kristofferson, and Natasha and Daniel Bedingfield have variously done before him. The father, of course, the Abraham, or at least the son of the father, the Avraham ben Avraham Avinu, the Charlton Heston of redemption rock, is Johnny Cash, a man of intense spiritual certitude, and enormous wealth and fame, who, in death as in life, remains an example of what it might mean to live as a Christian in an age of celebrity and superabundance: his aims were high and lofty; his life was an absolute mess.

In his thorough and entertaining authorised biography of Cash, Steve Turner establishes a suitably saintly tone on the first page. ‘It was doubtful,’ he writes of his subject, ‘whether he had a bodily organ that hadn’t been operated on, an area of skin that hadn’t been gashed, or a significant bone that hadn’t been cracked.’ This sounds like an entry from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, and Turner – the author also of Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song and a biography of Cliff Richard – can’t be unaware of the implied contrast with the Paschal lamb of Exodus 12.46 and the fulfilment of the Scripture in the Gospel of John, chapter 19 (‘Then came the soldiers, and brake the legs of the first, and of the other which was crucified with him. But when they came to Jesus, and saw that he was dead already, they brake not his legs … For these things were done, that the scripture should be fulfilled, A bone of him shall not be broken’). As with the saints of old, Cash’s afflictions and repulses – his brokenness of body and of spirit – are seen as spiritual tests and trials, and he is venerated for his sufferings. ‘As Cash’s eyes and legs grew weaker, his faith appeared to grow stronger,’ Turner writes of Cash’s last illness. ‘In his final years, as Cash was gradually stripped of everything – his sight, his mobility, his strength, his looks and, at the end, his wife – he became more confident than ever in the object of his faith.’ Tried and tested, Cash comes forth as gold.

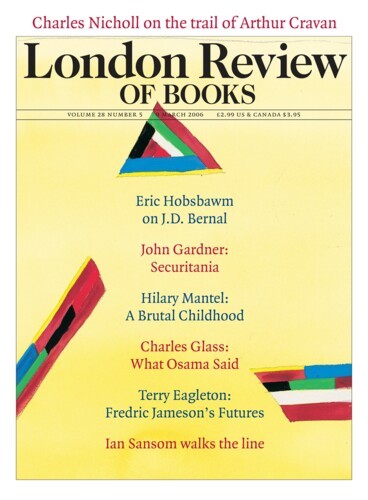

In James Mangold’s much-hailed biopic, Walk the Line, the mythic retelling of Cash’s story is, naturally, Greek rather than Christian, Hollywood’s standard method being to take the legacy and the legends of the Greeks and to give them a little Christian twist or kink, much as, say, Aquinas did with Aristotle, or as T.S. Eliot does in his plays. In Walk the Line, Joaquin Phoenix, playing Cash, is clearly on a mythic journey: there is first the early trauma, the violent death of Cash’s older brother; then there’s Cash out on the open road, the young virile male full of ambition and confusion and aggression; then comes the encounter with the goddess-figure embodying both purity and danger (June Carter, played with great enthusiasm and almost entirely with her teeth by Reese Witherspoon); and in the end, of course, rescue. Mangold’s Cash is no saint; he’s Odysseus.

We shouldn’t take any of these stories, Christian or Greek, at face value. In Killing Yourself to Live – well worth reading if only for its hilarious sociobiological explanation for Led Zeppelin (to be found on pages 198 to 200 if you happen to be in a bookshop) – Chuck Klosterman rightly points out that ‘rock ’n’ roll is only superficially about guitar chords, it’s really about myth,’ a truth which would doubtless be universally acknowledged by all teenage boys if they could just cease strumming for a moment and stop fiddling with their hair.* Ruth Padel is not a teenage boy and in her brilliant, frantic, wide-ranging I’m A Man (2000) she makes the connections between rock and myth absolutely plain (partly by using capital letters):

JIM MORRISON FOUND DEAD IN BATH IN PARIS? Wife Clytemnestra and lover murder Troy veteran husband in bath. MARVIN GAYE SHOT BY DAD IN BEDROOM? Oedipus kills father at crossroads. HENDRIX CHOKES TO DEATH IN HOTEL? Ajax stabs himself on beach. MANAGER ROMANCES BABY SPICE IN HOLIDAY HIDEAWAY? Zeus rapes Europa in Crete.

In an entirely other kind of brilliant, frantic, wide-ranging book, the theologian and ex-nun Karen Armstrong’s spiritual autobiography The Spiral Staircase (2004), we are reminded that ‘the myths of the hero … are not meant to give us historical information about Prometheus or Achilles, or for that matter about Jesus or the Buddha’ – or, we would wish to add, Johnny Cash. ‘Their purpose,’ Armstrong concludes, ‘is to compel us to act in such a way that we reveal our own heroic potential.’ In books, and on film, Johnny Cash is an inspiration. In real life, like the rest of us, he was corny and absurd.

Cash was not a great musician: his voice, a bass baritone, twangs and wobbles and is extremely restricted in range. His band, The Tennessee Two (Luther Perkins on guitar and Marshall Grant on bass, later augmented by W.S. ‘Fluke’ Holland on drums) were mechanics, and they sounded like it. In his eponymous autobiography Cash claims that ‘Marshall and Luther limited me, it’s true, especially in later years.’ (Perkins died in a house fire in 1968; and Grant was eventually and famously fired by Cash, by letter. Interviewed by Turner in The Man Called Cash, the clean-living Grant is clearly still bitter, and extremely scornful of Cash’s self-exempting holiness: ‘If you want to make something of yourself and come back to your family then that’s what you’ve got to do. It’s a matter of self-control. That’s all it is. That applies to everybody.’) Perkins on guitar was almost comically inept, and indeed renowned as being so; the band’s early song ‘Luther Played the Boogie’ seems an acknowledgment of the fact: ‘Now didn’t Luther play the boogie strange?’ sings Cash, as Perkins fumbles behind for notes.

But then Cash could hardly boast about his own skills. Although he was what would now be called a singer-songwriter, very few of his best songs are his own: Turner notes that the words and melody of ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ were lifted from a song by Gordon Jenkins, who reached an out-of-court settlement with Cash in the late 1960s. ‘Ring of Fire’, ‘Boy Named Sue’ and ‘The Ballad of Ira Hayes’ were all written by others; likewise, cover versions of Cash’s songs are often an improvement on the originals; see, for example, Waylon Jennings’s unsurpassable up-tempo ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ (from Heartaches by the Numbers), or Nick Cave’s appropriately dirge-like ‘The Singer’ (from Kicking against the Pricks). Shelby Lynne’s execrable ‘I Walk the Line’ is, admittedly, an exception to this rule.

Despite his obvious limitations, Cash churned out records, dozens and dozens of the damned things, including concept albums such as Blood, Sweat and Tears (1963) and Bitter Tears (1964) – which celebrate the lives of the American working man and Native Americans – and in 1966 the novelty album Everybody Loves a Nut, which includes ‘The Bug that Tried to Crawl around the World’, ‘The One on the Right Is on the Left’ and ‘Dirty Old Egg Sucking Dog’ (‘Egg-suckin’ dog I’m gonna stamp your head in the ground/If you don’t stay out of my hen house/You dirty old egg-suckin’ hound’). Like a lot of country singers, Cash clearly had some quality-control issues, but he also had a sense of humour; the one may indeed be the result of the other. The legendary album At Folsom Prison, for example, features him singing not only ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ and ‘Cocaine Blues’, but also the Jack Clement number ‘Flushed from the Bathroom of Your Heart’, which has the chorus, ‘I’ve been washed down the sink of your conscience/In the theatre of your love I lost my part/And now you say you’ve got me out of your conscience/I’ve been flushed from the bathroom of your heart.’ Even Cash’s best-known song, ‘A Boy Named Sue’ (which reached number two in the Billboard chart in 1969), lyrics by Shel Silverstein, is more joke than song, about a man who gives his son a girl’s name, because he thinks it’ll toughen him up. When Cash sings it live, on At San Quentin, you can hear the prison inmates go wild; goodness only knows what they’d have done had he decided to perform his version of the excruciatingly sentimental barbershop favourite, ‘Daddy Sang Bass’.

Despite his carefully cultivated outlaw image – he liked dressing up as a cowboy, presumably in imitation of Gene Autry – Cash was never actually sent to prison, although he did spend a few nights in police cells for drug-related offences: he was, after all, for almost his entire adult life a drug addict, addicted to amphetamines, to barbiturates, and, later, to sleeping pills. When not out of his mind on Dexedrine or Benzedrine or painkillers he spent his time appearing on The Muppet Show, and in Columbo, and in Little House on the Prairie (and of course The Simpsons) and doing numerous voice-overs and adverts for car manufacturers. He was also the author of a novel, Man in White (1986), about the life of St Paul, with whom he liked to compare himself: ‘Also interesting, for me at least,’ he writes in Cash (1997), ‘were the parallels between Paul and myself. He went out to conquer the world in the name of Jesus Christ; we in the music business, or at least those of us with my kind of drive, want our music heard all over the world.’

Cash was best friends with Billy Graham and in 1977 was ordained as a minister by the Christian International School of Theology and started holding services at his House of Cash, his operational HQ and recording studio in Hendersonville, Tennessee, which also featured a museum displaying a part of his vast collection of mementoes, curios and tat – including a desk set that once belonged to Chiang Kai-shek and a chair which had apparently once entertained the ample behind of Al Capone – and where his mother worked in the gift shop. As befits his name, Cash was a man with a profound interest in the ringing sound of tills: in Cash he claims that ‘the 1970s for me were a time of abundance and growth, not just in terms of finances and property, but personally, spiritually, and in my work.’ Note the order of priorities. The 1980s, however, were neither so rich nor abundant: Cash and his family suffered a brutal robbery at their mansion house, Cinnamon Hill, in Jamaica; he was savaged by his pet ostrich, Waldo; his father, Ray, died; he had heart bypass surgery and was in and out of the Betty Ford Clinic; and by 1986 he was without a recording contract for the first time in his long career. It wasn’t until the 1990s that things picked up again, when Rick Rubin, the founder of Def Jam records, and the man responsible for the Beastie Boys and LL Cool J, persuaded Cash into the studio to sing weird cover versions of other people’s songs. Even these popular late albums – American Recordings (1994), Unchained (1996), American III: Solitary Man (2000) and American IV: The Man Comes Around (2002) – on Rubin’s American Recording Company label are distinctly mixed blessings. Cash’s covers of Trent Reznor’s ‘Hurt’ and Depeche Mode’s ‘Personal Jesus’ may be rightly celebrated, but his dire, chug-a-lugging ‘Bridge over Troubled Water’, ‘Desperado’ and ‘Danny Boy’ would make even a retired Irish show-band performing one last time late at night in the back room of a pub in Kilburn want to hang their heads in shame and go back home to the wife and children and stick out their final years working for Balfour Beatty in order to pay off the mortgage.

So how did Cash become a saint and a hero? How on earth did it happen? It helps that he’s dead, of course, death being pretty much guaranteed to increase anybody’s chances of immortality: when he’s dead and gone, there’ll doubtless be glossy magazine features on the enduring legacy of James Blunt. You can’t rely on death, though, to do all the work for you. During his lifetime it certainly seems to have helped Cash that he was ruthlessly determined in pursuit of his goals. In the kind of sentence that might be found in any book about any so-called artist, Turner writes: ‘Cash clearly felt that he was a misunderstood man – that Vivian not only didn’t understand the demands of his work but couldn’t accept his mercurial artistic temperament. June, on the other hand, he felt loved him for who he was.’ We’ve heard that one before. After years of anguish, Cash eventually left his first wife, Vivian, with whom he had four daughters, and married June Carter in 1968. In his autobiography he recalls an incident backstage when June offered to iron his shirt: ‘I jerked off the shirt and threw it to her. She ironed it, and I went on stage in a nicely pressed shirt. Thus began her lifelong dedication to cleaning me up, and my lifelong acceptance of that mission.’ Never mind Lives of the Saints; the esteem and assurance of heaven should surely go to the wives of the saints: the list of angelic long-suffering wives, if not endless, is certainly extensive, and June Carter had a headstart on most of them as she’d already been married twice, and she played autoharp.

But no wife can make a man’s career. You also need a good manager, an agent, a producer, a band, a crew, guitar techs: in an extraordinary chapter in his autobiography Cash acknowledges the many people who helped him and June over the years, including ‘our staff in Jamaica’, security chief Armando Bisceglia, Peggy Knight, ‘the best Southern cook in the world’, and also Bob Wootton, the replacement guitarist for Luther Perkins and the driver of Cash’s big black tour bus, in which he criss-crossed America, playing stadiums and theatres and festivals and just about anywhere that would have him, week in, week out, year in, year out. Cash laboured hard for his help; he’d come a long way for a share-cropper’s son from Arkansas, listening to Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Jimmie Rodgers on the family’s big old Sears Roebuck radio. During the late 1950s, according to Turner, Cash was already travelling ‘300,000 miles a year’ on tour and when you hear him sing ‘I’ve Been Everywhere’ on Unchained, his voice a shadow of what it was even a few years previously on American Recordings, it really does sound like he means it: ‘He asked me if I’d seen a road with so much dust and sand,/And I said: “Listen, I’ve travelled every road in this here land/… I’ve been to Reno, Chicago, Fargo, Minnesota,/Buffalo, Toronto, Winslow, Sarasota,/Wichita, Tulsa, Ottawa, Oklahoma,/Tampa, Panama, Mattawa, La Paloma,/Bangor”,’ etc, ad nauseam. Along the way Cash worked with some very talented musicians, and quite a lot of them happened to marry his daughters: Rodney Crowell, Nick Lowe, Howie Epstein. If he couldn’t actually bring them into the family fold, then Cash at least did his best to get them on his cosy prime-time ABC TV vehicle, The Johnny Cash Show, which ran from 1969 to 1971. Recorded at the old Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, the home of the Grand Ole Opry, the opening programme featured Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell; other guests included Merle Haggard, Mama Cass, Odetta, Linda Ronstadt, Ray Charles, Judy Collins, Burl Ives and Kris Kristofferson. The show first aired in September 1969; in February of that year Cash was busy recording with Dylan (they duet, kind of, on ‘Girl from the North Country’, the first track on Dylan’s underrated, shambling Nashville Skyline, for which Cash wrote the liner notes); the month before that, Cash was playing for the troops in Vietnam; the month after, he was recording the San Quentin album. No wonder that by the end of the year his records were outselling The Beatles.

His ceaseless toil doubtless helped to secure Cash his wide and loyal fan base: it wasn’t just the inmates of high security prisons who loved him; American presidents loved him also (he played for Nixon at the White House). Quentin Tarantino loves him; Dylan loves him; and Snoop Dogg; and Pharrell Williams; and Ozzy and very probably Sharon Osbourne feel the same; old women love Johnny Cash; and young men love him too. Even Nick Tosches – the Donald Davie of rock criticism – likes him, at least a little bit. Walk the Line is probably the only film that both I and my wife, my mother-in-law, my sister, my son, and the entire population of Camden Town and Middle America have all been united in wanting to go and see, excepting perhaps Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit (which was a disappointment). Cash’s reputation may be as a singer who sings about troubles and vexations, and tortured and twisted souls, but like a little plasticine mongrel he is in fact top-quality, all-round family entertainment; man’s best friend.

Quentin Tarantino is quite correct – in his liner notes to Murder (2000), a compilation of Cash’s murder ballads – to state that ‘Cash sings of men trying to escape. Escape the law, escape the poverty they were born into, escape prison, escape madness, escape the people who torture them.’ But Cash also sings about men working the land, and driving trucks, and eating dinner with their families, and fishing, and falling down on their knees and accepting Christ into their hearts. You can tell that an artist has achieved true cross-over appeal when it’s possible to pick and choose tracks by them for your iPod by album title alone: you may not wish to download anything from Hymns by Johnny Cash (1960), The Christmas Spirit (1963), From Sea to Shining Sea (1967), America: A 200-Year Salute in Story and Song (1972), Rockabilly Blues (1980) or Country Christmas (1991), but you can be sure that somebody out there does.

Cash wasn’t really country, he wasn’t gospel, he wasn’t folk, he wasn’t rock, he wasn’t rockabilly, but he was enough of a little bit of all of them to satisfy the fans of each. Nothing he did was ever as pure as anything by Jimmie Rodgers, or Hank Williams, or Ernest Tubb, or the Louvin Brothers, but then teenage boys and even old ladies really don’t want pure; critics and specialists want pure, which is why they’re always so bitter and disappointed; the rest of us are happy to take what solace and comfort we can from wherever we can. What Cash’s style resembles most closely in fact is the ‘psycho-billy Cadillac’ in his 1976 song ‘One Piece at a Time’, about a car put together with odd bits and pieces stolen from the General Motors factory in Detroit and smuggled out in a lunchbox (with the memorable pay-off line, ‘Well, it’s a ’49, ’50, ’51, ’52, ’53, ’54, ’55, ’56, ’57, ’58, ’59 automobile’). Like the car, Cash was a hybrid, made up of many parts: he appeared in films (A Gunfight, 1970, with Kirk Douglas); he played in prisons (first performing inside in 1957); he campaigned on behalf of Native Americans, and against the Ku Klux Klan; he opposed the Vietnam War; and in 1973 he released an album, Gospel Road, the soundtrack to a self-financed film based on the life of Jesus. His audience was thus the dream demographic – black and white, old and young, secular and religious, right and left. He was all things to all men, and remains so: my son’s best friend, aged eight, knows all the early Sun recordings inside out and has the Solitary Man poster on his bedroom wall. Visiting my wife’s cousin in Donegal last summer – a Presbyterian minister, a man of genuine and deep seriousness who refuses to call Israel ‘Israel’ and who campaigns tirelessly for social justice – I asked him what sermons he was working on: he was working on a series of sermons about Johnny Cash.

Cash’s was a big life with broad appeal, which he successfully made seem even broader. ‘Many times in his writing,’ Turner notes, ‘Cash appears to embellish basic facts to make his story more compelling,’ which is a polite way of saying that he made things up. There’s the famous Nickajack Cave incident, for example: Cash claimed he was so strung out on drugs in October 1967 that he crawled into a cave near Chattanooga to die. The means of his deliverance from this certain death changes from telling to telling, and Turner points out that Cash doesn’t in fact refer to it at all in his first autobiography, Man in Black (1975), though later he claims to have crawled out and to have been met by June Carter and his mother, and in yet another account it’s June who goes into the cave to rescue him. It’s possible Cash may simply have been confusing himself with Orpheus, mistaking his mythic persona for his actual personality; he was, after all, into branding when branding was still something you did to a cow.

His self-identification as the Man in Black – he even wrote a (terrible) song about it – has been variously explained (when starting out, the only smart clothes that he and the Tennessee Two had to wear were black), but whatever the original reasons, it worked as the ultimate trademark and signifier. As a look, it works on stage and in photographs; written down and in print, the words clearly indicate the kind of material you might expect such a man to sing: something dark, and rebellious, with a serious and permanent meaning. John Harvey notes in his book Men in Black (1995) that what he calls ‘emphatic’ black ‘tends to play a double game with time … Black fashions … have tended to endure: to be anti-fashion fashions with a power to persist.’ Even now, looking at photos of Cash, you can’t deny his courtly magnificence, which comes partly from his natural physical shape and size, but largely from his symbolic use of what Harvey calls a ‘paradox-colour’. These days, if you look at photographs of Elvis in his prime he looks like a twerp, while Cash, part-priest and part-cowboy, could still cut it as a hipster. In the later album covers for the American recordings Cash’s body, despite his age, becomes a mountain of fortitude: big heavy coats, hooded eyes, white hair, a suggestion both of deep earnest thought and the lifelong indulgence of fleshly appetites.

Joaquin Phoenix is undoubtedly better looking than Cash – Phoenix looks like a movie star, while Cash was more rudely stamped – but in Walk the Line he does his best to re-create Cash’s slightly bloated, lop-sided look, the main difference being that while Cash looked pained, Phoenix throughout the film looks as if he’s actually in pain; you keep thinking any minute he’s going to throw up: someone needs to tell him that intensity is not the same thing as nausea. But Phoenix does seem to get the movements right, the way Cash would swing the guitar round to his back while singing, and the way he leans menacingly in and out of the microphone. There’s a point at which a movement becomes a signature and that guitar on the back, face up close to the mike, is definitely Cash’s own, though Joe Strummer used to try and imitate it, and now so does that man out of Green Day, though frankly they look like they’re wearing daddy’s clothes.

All of this obviously goes to make Cash the man and the myth – the clothes, the toil, Sam Phillips at Sun Records the great blessing at the start of his career, and Rubin the blessing at the end, and June Carter helping to keep him on the rails along the way – but what actually made him great was the simple quality of his voice, without which none of the rest of it would have mattered, but which is of course the most difficult thing to write about and to try and describe.

By a complete fluke I can remember exactly where and when I first heard Johnny Cash’s voice. I know that it was the summer of 1981, because my friends were leaving school, and I was a year younger than them, and we were in a band together. I know also that it was in my friend Paul’s house, his front room, because that’s where we used to practise: Paul’s dad worked on a Saturday, and we were allowed to practise in the front room because we didn’t have a drummer – we never could find a drummer, Ongar in that regard no different from Tennessee. I know that Paul had the bass guitar from the school music cupboard – because he was the bass player – and my other friend Mark and I had old nylon-string classical guitars from jumble sales or somewhere, and we must have known at least three chords between us, and we were assuming that pretty soon we’d be on the Peel Show and then before we knew it there’d be a call and we’d be touring with The Fall, or The Pyschedelic Furs, injecting heroin and hanging out with Lou Reed whenever he was coming over to visit our part of Essex. I know that we would have been desperately trying to reproduce the music we liked to listen to: Echo and the Bunnymen, but they were way beyond us (Will Sargent was actually a pretty good guitarist); and The Teardrop Explodes, but they had too much brass; and The Jam, which was surprisingly difficult, because of Bruce Foxton’s fiddly bass. It’s not until you’re about fifteen years old and you’re trying to play along with your favourite band that you realise exactly how difficult it is to shift smoothly even from a G chord to an A to an E; The Clash we could just about manage, but without a Topper Headon of our own, ‘Guns of Brixton’ and ‘London Calling’ did sound a little hollow. I know for sure that Paul had an older brother, Malcolm, who had loads of records and we were working our way through them, to see what suited us – Leonard Cohen, The Velvet Underground, Television – and I know that by chance one of Malcolm’s albums happened to be Johnny Cash at San Quentin, and we must have put that on, and it turned out that ‘I Walk The Line’ is not that difficult (I’m trying to pick it out now, trying to remember; I think it’s A, E, D, with maybe a B7 in there somewhere). We could do the boom-chicka-boom sound almost instantly and we all liked the voice: ominous and barely singing, close to talking, in fact, which was good because none of us could really sing either, and which is what makes Cash sound authentic and intimate.

You can hear that same quality in Cash’s voice – a determined and yet tentative quality, as though he were almost apologising for singing – if you go right back and listen to his first single, ‘Hey! Porter’ (released in 1955, with ‘Cry, Cry, Cry’), or to the second single, ‘Folsom Prison Blues’/‘So Doggone Lonesome’ (which reached number four on the Billboard country chart in 1956), or indeed if you listen to his very last album, American IV, when his voice is almost completely gone, and yet there it is – he still has it – on ‘The Man Comes Around’. Like reading Hardy, or Blake, or Larkin or other brilliantly skilled technicians, you listen to it and you think: ‘I could do that.’ But you can’t. It’s an illusion. In the notes to his 1977 album The Rambler, Cash writes: ‘Loneliness is real, the pain of loss is real, the fulfilment of love is real, the thrill of adventure is real, and to put it in the song lyrics and sing about it – after all, isn’t that what a country singer-writer is supposed to do, write and sing of reality?’ It is, and he did, and it’s not as easy as it looks. Even more difficult to live it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.