In the United States, there has been a lot of serious academic research – and some not so serious – into the curious phenomenon of the Hot Hand. In all sports, there are moments when an individual player or whole team suddenly gets hot, and starts performing way beyond expectations. When this happens, the player or team seems to acquire an aura of self-assurance that transmits itself to supporters, fuelling a strong conviction that things are going to turn out for the best. This sense of conviction then reinforces the confidence of the players in their own abilities, appearing to create for a while a virtuous circle of infallibility in which nothing can, and therefore nothing does, go wrong. The quintessential instance of the Hot Hand (which gives the phenomenon its name) occurs in basketball, where certain players suddenly and inexplicably acquire the ability to nail three-point baskets one after another (in basketball you get three points for any basket scored from a distance of over 23’9’’, a formidably difficult feat which means even the best players miss more often than they score). When a player gets the Hot Hand, his or her team-mates know to give them the ball and let fate take its course. Anyone who has watched a game in which a player acquires this gift will recognise the feeling of predestination that descends on all concerned: players, spectators, commentators (above all, commentators) just know what is going to happen each time the Hot One lines up a basket from some improbable position on the court. He shoots! He scores!

What the research shows is that all this – the sense of destiny, the effect it has on a player’s confidence, the virtuous circle – is an illusion. Exhaustive analysis of the data has revealed that making a sequence of three-point baskets has almost no bearing on the likelihood of making the next one, which remains determined by a player’s basic skill level (some players are more likely to make the shot than others, but that is just because they are consistently better at it, not because they are intermittently Hotter). What we experience as the Hot Hand is simply a result of the random distribution of chance, which determines that some players, inevitably, will string together a successful series of shots, just as if you get enough people tossing a coin, some of them will get heads 20 times in a row. We believe these sequences reflect a kind of destiny only because we are predisposed to remember the occasions when the sequence seemed to go on for ever, and forget all those other occasions when a promising little sequence went kaput. This is exactly the same as our propensity to recall and fixate on those very rare instances of dreams or horoscopes that appear to ‘come true’, as some must do under the law of averages, and to ignore the countless others which turn out to be groundless and are instantly forgotten. The Hot Hand, like astrology, is a fallacy, though there is some argument about whether or not it is an ‘adaptive’ fallacy, i.e. one we might have good reason to cling on to anyway, because it helps to remind predominantly self-interested, cocksure players that they are better off passing the ball to the best three-point shooters on the team. Whether adaptive or not, fallacies like this are evidence of a persistent human tendency to imbue randomly distributed events with magical properties, particularly when they conjure up an ability to peer into the future.

In sport, the magic that everyone is after is a sprinkling of the fairy dust of ‘self-belief’, that elusive quality that is so often said to separate out the winners from the losers. It turns out that really and truly believing the ball is destined to go through the hoop makes no difference. But this doesn’t mean that there is no magic out there. The clearest evidence that mysterious forces are at work on the sports field comes from the unarguable impact of home advantage in almost every kind of sporting contest (in professional basketball the home team wins about 66 per cent of the time, and in Premiership football the home team wins nearly 64 per cent of the available points). There has been a lot of academic work on this phenomenon, too, but there is nowhere near as much consensus about what is causing it. Some have argued that the advantage of playing at home derives from a series of ‘technical’ factors – away teams are tired by long journeys, have to sleep in uncomfortable hotel beds, may be unused to local playing conditions – which means that it is no different from the other technical advantages, such as fitness and skill levels, that players bring to a game. The problem with this view is that although the advantage of playing at home has declined somewhat over the century-plus history of professional sports, it hasn’t declined by much; meanwhile, the technical disadvantages of playing away have been greatly reduced by significant improvements in all aspects of travel: first-class flights, fancy hotels, on-site physiotherapists etc. These days, no big league team should ever arrive at an away game tired, tetchy, homesick (the top players lead such bicoastal, transcontinental, post-nuclear lives that it’s not clear what it would mean for them to be homesick anyway); yet winning away from home is still very hard.

Something else is clearly going on: something happens during a game that makes home teams raise their performance levels, and away teams drop theirs. In fact, it seems likely that two things happen, though no one is sure what their relation is to each other. First, even though football pitches and basketball courts are more or less the same, familiarity with one’s surroundings, however anonymous they might appear from the outside, seems to enhance confidence in the performance of repetitive physical tasks. Teams that move stadiums, even from one identikit arena to another, tend to sacrifice a big chunk of home advantage until they familiarise themselves with their new surroundings. The other thing that improves performance is an audience – any audience, so long as it is relatively benign (home advantage is more or less constant between the football leagues, regardless of the size of the crowds). Home fans like to think that what makes a difference is the noise they make, but in fact it seems that they make a difference simply by being there, and by wanting things to go well for their team. Away players, who can’t be nearly so confident of how the crowd will react when things go well for them, don’t have this advantage.

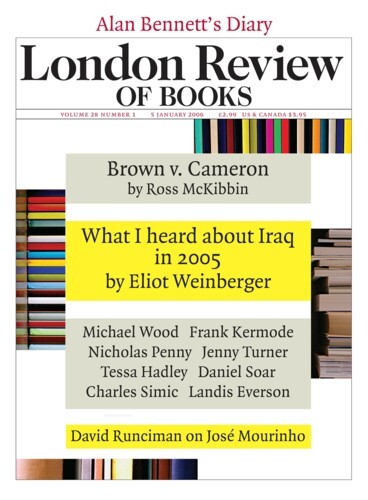

Where do modern football managers, those devotees of the gospel of self-belief, fit into this magical/mechanical universe? Can they, like the home crowd, really make a difference to their players’ innate abilities by instilling that ineffable something extra? Or are they, too, at the mercy of the Hot Hand, mere surfers on the inexorable waves of chance like everyone else? Patrick Barclay’s portrait of José Mourinho, with its subtitle ‘Anatomy of a Winner’, promises an answer to these questions. But in fact it simply confirms how little thought even the best football writers are willing to give to the workings of chance in the building and destroying of reputations. Barclay buys uncritically into Mourinho’s self-created myth which holds that he is ‘A Special One’, a manager who promises great things and then unfailingly delivers them. In the lazy phrase that Barclay uses as the title of his first chapter, Mourinho ‘does what it says on the tin’. The evidence for this is that Mourinho, fresh from delivering the Champions League title to his previous club, Porto, arrived in London in the summer of 2004 promising to make the difference for Chelsea, and within nine months had presented them with their first league title for 50 years. Barclay talks to a number of other coaches, including David Moyes of Everton, who originally believed that Mourinho had made himself a hostage to fortune by his blind faith in his ability to shape his own destiny: ‘The initial feeling was that you just couldn’t display that kind of arrogance in this country and get away with it.’ But when Chelsea swept all before them, Moyes also became one of the converted – here truly was a manager with something special to add.

Barclay values his opinion because Moyes too had acquired something of a reputation by the end of the 2004-5 season: the ‘Moyesiah’, as he was known on Merseyside, for having guided Everton into an improbable fourth place in the Premiership and a slot in the Champions League. Since the publication of the book some of the gloss has come off Moyes’s image as a miracle-worker, after his team were dumped out of Europe by Dinamo Bucharest, and have since found themselves scrabbling around near the relegation places at the bottom of the Premiership. Has Moyes lost it? Of course not – it’s just called reversion to the mean. Everton’s success last year was based on a fortunate sequence of wins (many of them achieved by a single goal) that happened to fit snugly into the confines of an English league season. Moyes’s overall record as manager of Everton (looking at more than 150 games) shows that his team wins about as many games as it loses, making him a pretty typical manager of a pretty typical mid-ranking Premiership club. But slice and dice this record into bite-sized sequences and you can get either the saviour of last season or the duffer of this. Moyes is simply suffering from a glorified version of what is known as the Curse of the Manager of the Month. The Manager of the Month award is itself an absurdity – doled out in each of the leagues to whoever has happened to preside over an improbable run of four or five wins. Surprise is then expressed when these teams, supposedly under the charge of some touchline guru, lose their next game, as they often do. It’s not inevitable that they should lose their next game, of course: the Manager of the Month wins some and loses some. It’s just that we remember the losses, and dress them up into a curse, because we can’t distinguish between statistically meaningless sequences and the march of destiny.

Mourinho has no intention of being a typical manager of a typical middle-ranking club. When he arrived at Chelsea, they were a team of underachieving superstars bankrolled by the world’s most affluent thirtysomething. Mourinho insisted they could do better and, after he had spent quite a lot more of Roman Abramovich’s money, do better they did. But Barclay has mistaken cause and effect. Chelsea didn’t do better because Mourinho said they would; rather, he said they would because he knew that as an underperforming team they were very likely to improve. Mourinho, who is an intelligent as well as a ruthless man, knows that the most important thing for a football manager’s reputation is being in the right place at the right time. It’s not that he does what it says on the tin so much as that he waits until he has a pretty shrewd idea of what is in the tin, then puts his own label on it. Take the business of managerial ‘mind games’, of which it has now become an article of faith among the British press that Mourinho is the new master, having inherited this crown from the previous champion, Alex Ferguson. Ferguson’s claim to a place in what Barclay calls ‘the mind games hall of fame’ is always traced back to the moment in 1996 when his goading of Newcastle’s manager Kevin Keegan produced a spectacular outburst from a wild-eyed Keegan live on Sky TV (‘I’d love it if we beat them, love it’ etc). This is generally recognised as the moment when Newcastle lost the title, after having led Manchester United for most of the season. But Newcastle didn’t lose the title because Keegan started foaming at the mouth on television; he was foaming at the mouth because he knew Newcastle were about to lose the title, out on the field, where they had been unable to sustain their (slightly freakish) early season form. There is no evidence that the provocations the top managers now routinely offer to each other through the press have the slightest bearing on the outcome of matches. Mourinho knows this, but he also knows that everyone concerned – the managers and the journalists – has an incentive to pretend otherwise, in order to build their own part up. So he is happy to oblige.

The reason Ferguson’s mind games no longer have the impact they once did is not because he has been out-psyched by Mourinho, but because Manchester United are not the force they were. Mourinho will have been aware when he arrived in England that there are only three teams that currently have the resources to challenge for the Premiership title, and that two of them are currently very much overstretched. Chelsea not only have Abramovich’s billions behind them; they also face two rivals who have got themselves massively, and somewhat precariously, in debt – Arsenal to fund their move to a new stadium, Manchester United to finance their takeover by the Glazer family. Both Ferguson and his Arsenal counterpart, Arsène Wenger, are finding that their managerial skills count for little in the face of brute economic reality. In Ferguson’s case this has produced a state of semi-permanent rage against the dying of the light, as he desperately tries to reassert control over his own destiny. Like a man to whom he is sometimes compared, Tony Blair, Ferguson could and should have quit a couple of years ago. But both men have come to believe in their own myth, which insists that it is they who made the decisive difference to the success of their own teams, and it is they alone who can keep them at the top.

What this myth ignores are the deep structural factors, and the luck, that permitted them both to remain unchallenged at the top for the best part of a decade; above all, it neglects the good fortune they had in the relative weakness of their opponents (Ferguson’s ascendancy had as much to do with the decline of Liverpool, from which he benefited but for which he has taken much of the credit, as Blair’s had to do with the demise of the Tory Party). Ferguson believes his current travails risk overshadowing his earlier achievements, which is why he is so desperate to cling on until things improve, in order to secure his legacy. He also believes that he has not had the credit he deserves for turning Manchester United around in the early 1990s, particularly financially. Like Blair, Ferguson has the misfortune to be surrounded by people who are a lot richer than him, many of whom made their money riding the gravy train that Ferguson believes he was responsible for setting in progress. It is his sense of grievance that he has not had his just rewards for presiding over the transformation of Manchester United from a £20 million to a near £1 billion business that fuels his inability to let go. The tragedy is that by hanging on into a period of decline he has revealed how incidental his own presence may have been to that initial success.

Ramsey, Busby, Shankly, Revie, Stein, Clough, Robson, Dalglish, Graham, now Ferguson, and possibly Wenger too: the careers of the great managers, like those of politicians, tend to end in tragedy, or at least in bitter disappointment, as they cling on for too long. Mourinho believes not only that he belongs in that list by dint of his achievements, but that somehow his fate can be different. Is he any different? He certainly has one claim that makes him stand out, even in a list of this kind: he has already achieved success at more than one club, which puts him in an elite within the elite, alongside Clough, Robson and Dalglish but very few others (though there are some more examples of multi-club success on the Continent, in the likes of Fabio Capello. The real measure of Mourinho’s stature lies with what he achieved in the two years before he came to Chelsea, as the manager of Porto, where he won the Portuguese championship two seasons in a row. The icing on the cake came in 2004, when Porto also became champions of Europe, but that, as in all knock-out competitions, owed a good deal to luck (in this case a very fortuitous victory over Manchester United in the last 16, courtesy of a last-minute goal after United had had a perfectly good goal ruled out for offside). His successes within Portugal were not just luck, however: he took a poor team and turned them within a matter of months into the dominant force in Portuguese football, bringing in new players, changing the side’s tactics and insisting on discipline. He revealed himself to be ruthless, shrewd and highly effective. Sometimes, it appears, a manager really can make the difference. So what is different about Mourinho?

As Barclay points out, the thing that most obviously sets him apart from many of his peers is that he is not himself a former professional player (he tried, but failed, not even managing to be picked for the Portuguese club side his father was managing). Rather than playing the game, Mourinho studied it, first at university, and then in various coaching and other capacities at a series of clubs in Portugal and Spain, including finally as Bobby Robson’s assistant at Barcelona. Barclay is keen to quote those, like the UEFA director of coaching and former Scottish national coach Andy Roxburgh, who believe that Mourinho is a shining example of what can be achieved by the right sort of education. The fifteen years he spent observing the methods of different coaches, from his father through to Robson and Louis van Gaal at Barcelona, constituted what Roxburgh calls ‘the finest example of work experience in the history of employment’. The implication here is that managerial greatness is something you can learn, if you are willing to spend enough time watching other coaches in action.

And yet all those who report on Mourinho’s own coaching methods testify that he is very much his own man, and that he tends to rely less on his own experiences than on a series of carefully compiled technical dossiers that break the game down into a series of controllable variables, which he then does his best to control. If so, it seems that the formative years were not the ones he spent at Barcelona, but at university in Lisbon, where he learned sports science. Barclay, like all managerial myth-makers, wants us to believe the opposite, that there is more to Mourinho than simply playing a percentage game – ‘painting by numbers’ as he dismissively calls it. He is keen to emphasise the pearls of wisdom that pass down among the elite managers, those arcane secrets of the coaching trade known only to insiders. Unfortunately, the examples he gives of these are so banal, and laughably imprecise, that they make astrology sound like a hard science. Here, for example, is Robson’s golden rule of crisis management, as revealed at a conference of international coaches organised by Roxburgh for UEFA: ‘Keep calm – and always give the other coach a problem. Don’t just send on a big striker for a big striker. Change it. Give your opponent things to think about.’ This is the sort of wisdom that Roxburgh thinks a novice like Mourinho could have gleaned about management only by working with Robson. The fact that Robson himself derived this lesson from a single, freakish match (when he replaced two defenders with two attackers in a game Barcelona were losing 3-0 but went on to win 5-4) and the fact that the one time Mourinho tried to follow his example it failed miserably (he substituted three players at half-time in a cup match at Newcastle that Chelsea went on to lose) are by the by. As with astrology, nothing is allowed to get in the way of a good story.

In truth, it seems likely that what Mourinho learned from his years of work experience was not what to do, but what not to do. The advantage the non-player has over the ex-player is that they can trust in the hard evidence of percentage football, without the memories and fantasies of their playing days getting in the way. There is little enough that it is possible to control on a football pitch anyway – it has been estimated that only 5 per cent of the action is exclusively subject to the differential skills of the players and the tactics of the team, the rest being shaped by such chance or inconsequential factors as the bounce of the ball – without sacrificing what advantages you have to romantic impulses. Everything suggests that as a manager, Mourinho, by way of contrast to Robson, is neither romantic nor impulsive. His teams are well-organised, highly disciplined and give nothing away. Five per cent might not be much, but if you squeeze every drop of advantage out of the things you can control over the course of a season you will grind your opponents down. The key is not to be distracted by all the nonsense that wafts around the other 95 per cent, much of which gets reported as fact, as it is reported by Barclay here. If you can get your opponents to believe that you believe in the nonsense, too, then so much the better.

Even Barclay notices that Mourinho’s special gift is the remorseless attention he pays to detail, though he treats this as though it were some kind of magic trick in itself. For example, when UEFA introduced the idiotic ‘silver goal’ rule into European club competitions – which meant that if a team was leading at the end of the first period of extra-time, the second period would be abandoned and the match end – Mourinho instructed his Porto players to adapt their tactics to this new 15-minute format. What Barclay, quoting Marcello Lippi, considers remarkable is that Mourinho didn’t express a view about whether the silver goal was a good or a bad rule, he just got on with the business of trying to extract some advantage out of it. What, you wonder, does it say about the other coaches that this value-neutral approach is taken as a sign of inspiration? Probably that most other coaches, corrupted by the highs and lows of their own playing days, have lost the plot: think of Glen Hoddle, who declared before the 1998 World Cup that England didn’t need to practise penalties, because penalty shoot-outs were all in the mind anyway. With enemies like these, who needs friends?

Mourinho has got one other thing going for him that no one who has watched him in action can fail to notice. He is astonishingly good-looking. Barclay is metrosexual enough to be able to discuss this without embarrassment, but he prefers to call it ‘presence’, comparing Mourinho to charismatic but hardly swoon-inducing men like Bill Shankly and Brian Clough. What he has in common with Clough and Shankly is that the players appear desperate to do whatever it takes to win his approval, like schoolgirls fighting for an approving glance from their favourite teacher. Barclay turns to Desmond Morris to explain what is going on here, citing the Chelsea players’ body language as evidence that some profound human forces are at work – not just ‘respect’, not just ‘camaraderie’, but something like ‘love’. This may be overstating it. Mourinho, as well as being very handsome, is always nicely turned out, something that almost all modern professionals take extremely seriously. Ryan Giggs, for example, put the extraordinary impact of Eric Cantona on Manchester United down to the fact that not only was he a gifted player who trained hard, but also that his idiosyncratic, classically French wardrobe put the rest of the team to shame. In Giggs’s words, as a dresser Cantona was simply in a ‘different class’.

This is one of the things that make it hard to be sure who was really responsible for the transformation of United’s fortunes during the mid-1990s: were the players galvanised by the presence of the manically chewing, red-faced Scotsman on the touchline in a puffa jacket for whom they had been underperforming for years, or was it the search for a nod of approval from Cantona, with his appraising peacock stare, that drove them on? (Admittedly, it was Ferguson’s decision to sign Cantona, as it was his decision to sign Roy Keane, whose terrifying, cold-eyed glare would make anyone want to stay in his good books.) At Chelsea, Mourinho smoulders at his players from the sidelines in a fetching array of suits and coats, top button of his shirt undone and tie slightly askew. Compare this to Liverpool’s equally methodical Rafael Benitez, whose team’s league performances have sometimes seemed strangely lethargic, and who paces the technical area in his ill-fitting suit and anorak like a slightly down-at-heel Spanish civil servant. Benitez, it must be said, appears to be a thoroughly civilised man and an excellent coach. But Mourinho recognises that it is part of a manager’s job to give his team the audience they need to perform.

The manager Mourinho sometimes seems to resemble best is, as Barclay points out, the one bona fide genius of the English game, Brian Clough, who also had his peacock side. In some respects, the two men look like polar opposites: Mourinho the obsessive technocrat, endlessly scribbling notes to himself, goading his players on, happy to push referees to the limits of their tolerance in the hope of gaining an advantage (and occasionally beyond their limits, as in the case of Anders Frisk, whom Mourinho helped to drive into early retirement with his absurd antics following Chelsea’s defeat in Barcelona during last season’s Champions League); Clough cavalier, impudent, genuinely funny (Barclay would have us believe that Mourinho is funny, too, but most of the time he is simply unpleasant, in a vaguely humorous sort of way), liable to haul his players off the team bus for a couple of beers in a lay-by en route to a match, insistent that his sides should never give referees a hard time, which they never did. In fact, the two men are different sides of the same coin. Both Clough and Mourinho saw that the secret to managerial success lay in avoiding all the bullshit that surrounds the game, and preventing their players from being distracted by it. Both have tried to keep the game simple, and to leave the wishful thinking to the other team. Some of Clough’s protégés were a bit fat, like John Robertson, or a bit clumsy, like Larry Lloyd; Mourinho’s are all lean and mean. But fat or thin, neither manager would ever let any of his players start to believe their own publicity. Both have consistently wanted their teams to believe in the manager, and to play for him, and that’s what their players, for the most part, have done.

Clough thought that his tragedy was being denied the opportunity to manage England, though in the end the real tragedy was obvious, as he succumbed to alcoholism. Mourinho, too, has declared that he will consider his career incomplete unless he gets a chance to display his talents at the helm of the Portuguese national side. This only goes to show that even the shrewdest managers have a tenuous grip on reality. The qualities that made Clough, and threaten to make Mourinho, pre-eminent among club managers don’t translate onto the international stage. No doubt various managerial reputations will be made or broken at the World Cup in Germany next summer. Already controversy is raging in Germany about the wisdom of entrusting the management of the national team to Jürgen Klinsmann, who has practically no coaching experience and continues to base himself in California. The German administrators have clearly decided what they need is a charismatic leader who has the respect of the players (the Dutch have gone down the same route by appointing the equally untried but even more glamorous Marco van Basten). Others, noting the success of the highly disciplined Greek team in the 2004 European Championship under their unfashionable manager, Otto Rehhagel, believe that what cuts it now is technocratic coaching expertise.

It is true that Mourinho is more or less unique in being able to offer both the glamour and the number-crunching. But neither is enough. Because national team managers are ultimately judged on their performance in knock-out tournaments that only come round every couple of years, they need three things above all: some decent players, a lot of luck and, if possible, home advantage. There simply isn’t enough scope to work the percentages as an international manager, and no amount of glamour on the touchline will save you if you get a bad break on your way to the final. If Germany win the next World Cup it will not be because of how they are managed, but because they are playing at home: of the last five teams who have had a realistic chance of winning the tournament on home soil – England in ’66, West Germany in ’74, Argentina in ’78, Italy in ’90, France in ’98 – only Italy failed to do so. Italy missed out in ’90 because they lost a penalty shoot-out, and whoever does win in 2006 will probably have to survive at least one shoot-out along the way. Glen Hoddle was wrong to think practising penalties doesn’t make a difference, but even Mourinho would have to accept that the advantages you gain by practising only really tell in the long run (say, if all drawn matches were settled by penalties over the course of a domestic league season, in which case the best penalty-takers would probably win the league). In the one-off scenario of the World Cup finals, the fate of any manager remains in the lap of the gods.

If Mourinho wants to lead Portugal to glory in an international tournament, he has already missed his moment. Portugal will never get a better opportunity than they had in 2004, when they hosted the European Championship and reached the final, only to succumb to the Greeks by a single goal in an ugly, random-seeming game. Without home advantage Portugal would have to be very lucky indeed to get another chance to win a tournament at the highest level, and home advantage won’t come round again in Mourinho’s professional lifetime. Perhaps deep down he accepts this, which is why he is already looking beyond the national team, and beyond football, to wider horizons. Last summer he visited Israel, and gave an address to a joint conference of Israeli and Palestinian coaches in Tel Aviv. He told his audience: ‘When I have retired, when, in 13 more years I have finished with football, I can see myself 100 per cent involved in human actions. I have always thought about problems in the Middle East and Africa, not just about football.’ Barclay suggests a role perhaps at the United Nations, since Mourinho ‘has, after all, proved he can unite dressing-rooms’.

It is all so horribly familiar. I recently heard one of Tony Blair’s closest confidants tell an audience of students about the prime minister’s plans following his retirement: he wants to make a real contribution on the international stage, to bring his talents to bear on the big humanitarian issues, ‘like Bill Clinton, only more so’. Oh the fantasies these people have about the difference they can make.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.