At the entrance to the British Museum’s Persian exhibition, Forgotten Empire (on until 8 January), the King of Many Peoples looms high on a rectangular relief. He dwarfs the attendant who reaches up from behind to shade his big imperial head, ready with a towel to dab away the imperial sweat. His Highness (probably Xerxes) sits rod-spined on a high-backed throne, sceptre in one hand, lotus in the other, a footstool protecting his feet from the ignominy of contact with the ground. And the throne is itself enthroned, sitting on a greatly magnified image of itself, big enough to accommodate three tiers of subject peoples underneath: Armenians, Libyans, Greeks, Egyptians etc, arms upraised to bear his imperial weight – discretion not being one of the many qualities for which the ancient Persians are here being celebrated.

The relief is a cast made by the British on an expedition to Persia in 1892, a few years before the French connived with the Qajar Shahs to lock them out of Iranian archaeology for a generation. The Louvre has sent over some of the fruits of that arrangement, some interior decoration from the colourful palace at Susa, contours like piped icing filled in with pastel marzipan, while Tehran has loaned some of its most precious treasures, including the extraordinary silver foundation document in which Darius boasts of the size of his empire in three languages, together with its equally extraordinary plain stone box. Sponsorship is provided by BP, formerly the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, for the Franco-Persian agreement did not stop William Knox D’Arcy from undertaking a different kind of exploration. There is a lot of history and politics in this exhibition, and not all of it is ancient.

The original Xerxes remains where he has been for 2500 years, in Persepolis, a part of the great doorway into the lofty Hall of a Hundred Columns, through which Armenians, Libyans, Greeks and Egyptians walked once with gifts and expectations. And they will have noticed those subject peoples bearing the throne that bears the throne, and identified themselves.

The great audience-hall, or apadana, is characteristic of Persian imperial architecture, and characteristic of such halls are forests of sixty-foot columns sprouting out of bell-shaped bases petalled like inverted lotus blooms and topped by push-me-pull-you pairs of lions, griffins and human-headed beasts. The exhibition has several examples, flanked by more casts from the 1892 expedition, showing endless processions of subjects bearing jewellery, jugs, cups and, courtesy of the Bactrians, camels, across a parade ground punctuated by cypress trees, gifts for a king who, like the Wizard of Oz, is sometimes represented by a voice speaking in the first person – ‘Me Artaxerxes’ – or replaced with a completely empty space. The empty spaces once contained panels which showed Xerxes and the crown prince, say, receiving gifts. At some point the panels were removed to the treasury by one of his successors, either for safe-keeping or because it was too painful a reminder of a father or a brother dispensed with or usurped. Some of that tribute is on display around the corner, golden drinking horns and lotus bowls, some inscribed in cuneiform with Xerxes’ name (in three languages), bracelets, collars and other personal adornments, treasure which escaped the notice of Alexander and his men.

The exhibition has an unspoken focus on pure Persianness. There is no room here for the BM’s spectacular holdings from the western satrapies of Lycia and Caria, from the proverbial tomb of Mausolus, for example, or the Nereid Monument. Too Greek or, at least, not Persian enough. Apart from the oversized heads and push-me-pull-yous, Persian style seems to be found above all in the smoothness of the finished surfaces, a column-base in gun-metal grey, a big black guard dog polished like a precious stone, and bordering the smooth planes, the sharpest of edges, cut like a jewel. It is not exactly ‘truth to materials’ as Henry Moore would understand it, but perhaps as Eric Gill might understand it: there is truth, that is, to what stone is capable of in human hands, to its hardness, its cleanness, its neatness when worked by chisel, abrasive and buff, truth to sculpting, to the aesthetics of finish. There is not much sign, at any rate, of that Western tradition of making stone seem quite different from what it is, like cloth or pillows or flesh.

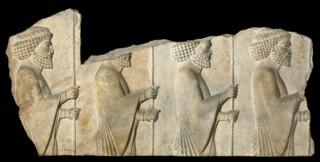

My favourite is a fragment of a frieze from the BM’s own holdings, plundered in a raid on Persepolis in 1811: four guardsmen with slicing pleats, as if machine-tooled, sporting beards and earrings, their tight little curls marshalled into a tight little grid. The alternation of smooth and sharp recalls Art Deco, though that of course is to get the influences the wrong way round, and the finishing gives the same sense of luxuriousness that Art Deco objects have. But this is more than a merely art-historical point. Sheen was political too, a quality, farnah, that the Kings of Kings were very proud of, as if they were themselves shiny objects illuminating the world with the reflected light of the great god Ahura-Mazda, probably to be identified in the little figure of a royal personage emerging from a winged disk who hovers like the Holy Ghost over kings and sacrifices, on doors and seals.

If Greeks are largely excluded, there is a quiet conversation going on with them nevertheless. A couple of vases show how Greeks saw the barbarians: they always made their trousers too tight, and got the uniforms mixed up. Part of a fine Greek statue of a woman was found in the treasury, probably booty, though the catalogue draws a veil over the possibility – the Persians here are good guys.* Not enough of the figure remains to identify it – though someone at some point decided it was Penelope waiting for her husband to come home – but the draperies, soft and bosomy, set up a nice contrast with the hard-edged guardsmen nearby. Greek sculpture suddenly seems a bit messy and chaotic, as if it is melting. An important part of this conversation is the dialogue between the Persians and the museum’s Parthenon frieze, a monument to the resurgence of Athens after the Persian sack. The Parthenon’s unique subject, a procession, probably owes something to the great processional friezes of the Persians, Athens’s imperial predecessors in the Aegean, for the Parthenon, like Persepolis, was paid for by tribute. And once the comparison is made, that much vaunted ‘freedom’ of Greek art, the freedom of composition, the relaxed poses of gods, the variety in similar figures, the freedom even of the stone to move and to be what it isn’t, no longer seems such an abstract idea.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.