The problem presented by Troy: Myth and Reality at the British Museum is not so much the myth as the reality (until 8 March). Troy was a tiny city in what is now the northwestern corner of Turkey. In the course of the first millennium bc, its sparse population fell under the successive control of Lesbos, Athens, Persia, Alexander, Alexander’s successors and then Rome. Straddling these shifting geopolitical plates was not good for its economy. In the late fifth century bc the city was supposed to pay just two talents a year to Athens in imperial contributions; archaeologists doubt it would have been able to manage even half that. Around 278 bc Asia Minor was invaded by the Gauls, who thought Troy’s ‘holy battlements’ would make a fine capital for their new kingdom. On seeing the site, however, they quickly moved on. A hundred years later a young man visited from neighbouring Scepsis and observed that this ‘village-city’ was in such a wretched condition that the houses didn’t even have roofs. Demetrius of Scepsis would eventually cause a large number of 19th-century Europeans to waste a great deal of time and money.

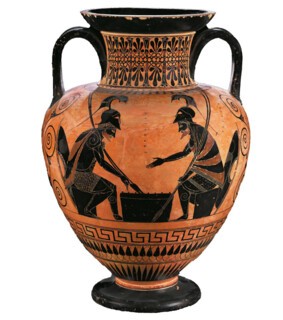

Of course the actual Troy has always existed alongside another Troy, the Troy of Helen, of the horse, of the war, of the imaginaire. Thankfully it’s mostly the imaginary Troy that is the subject of the BM’s exhibition. It begins with two top-quality artworks: a smooth salmon-buff amphora from around 530 bc, painted by the black-figure master Exekias, which shows a fat-thighed and metal-headed Achilles, his spear in the neck of Penthesilea; and next to it The Vengeance of Achilles (1962) by Cy Twombly, a massive scribbled ‘A’ with a bloodied point.

There is no such steel at the other end of the exhibition, where pieces include a wonderfully inert Dead Hector (1892) by Briton Rivière, a neoclassical Achilles from Chatsworth, with an arrow sticking out of his ankle, and a cartoonish Wrath of Achilles (1630) by Rubens. I had hoped, given that the Glyptothek is currently closed for refurbishment, that they might have been persuaded to lend one or two of their superb sculptures depicting the first and second Trojan Wars, originally from the temple of Aphaia (Homer refers more than once to Heracles’ earlier sacking of Troy). But Naples has been generous with its frescoes. One shows Helen being helped onto Paris’s boat and another Thetis collecting her son’s armour from Hephaestus, her appraising gaze reflected in miniature on the surface of the shield.

The sections between the Exekias and the Rubens mostly display ancient imaginings of the story of Troy, which decorated Athenian crockery, Roman sarcophagi and the domestic interiors of Pompeii. It’s all beautifully done: there is a ‘whirlpool’ wine bowl of c.575 bc showing the gods queuing to pay their respects at the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, and one from a century later showing Achilles fighting a duel with Memnon, king of the ‘Ethiopians’; as well as an amphora depicting Ajax, in full armour, passing one of the long days of the siege by playing a board game; another shows him falling on his sword. If you don’t remember many of these scenes from Homer, that’s because the number of myths about Troy (‘Ilion’ in Greek) has always greatly exceeded the contents of the Iliad.

There are few masterpieces but plenty of gruesome melodrama: Achilles dragging Hector’s corpse behind his chariot; Hector’s sister Polyxena trussed up like a parcel, her throat spattering Apollo’s altar with blood; Troilus, her younger brother, trying to escape swift-footed Achilles on horseback; and, a little later, Achilles brandishing Troilus’ severed head. Bits and pieces of recognisably human anatomy, caught up in Scylla’s monstrous coils, feature on a Roman table stand. A vase shows Achilles’ son Neoptolemus battering Priam to death with the body of Astyanax, his own grandson.

As early as 700 bc the imaginary Troy and the real Troy were believed to share not only the same name but the same geographical co-ordinates. Xerxes stopped at the city en route from Persia to Athens to sacrifice a thousand oxen to Trojan Athena, while his magi offered libations to the powerful ghosts of the heroes whose tombs had been identified across the region, overwriting the landscape with Homer’s cast of characters. At some point the inhabitants of Locris began to send two virgins each year to Troy, to atone for the rape of Cassandra by their ancestral king. The Trojans would lie in wait to capture the women, but if they escaped detection they found sanctuary and a lifetime of servitude in the temple of Athena, the very place where the sacrilege had occurred. Their duties included dusting the weapons supposedly left behind by Agamemnon’s army.

In May 334 bc Trojan tourism got a boost from Xerxes’ ultimate successor. Alexander the Great and his best friend, Hephaestion, anointed the tombs of Achilles and Patroclus respectively and raced around the burial mound in imitation of the funeral rites described by Homer. At Troy itself Alexander made sacrifices to Athena and the heroes, and expiation to Priam for the sacrilege of Neoptolemus. He looted armour from the temple and replaced it with more splendid pieces of his own. In all of this, the inhabitants of Troy took on the role of the heirs of Hector and Priam, even though the city was resettled after a hiatus of several centuries by people whose most obvious linguistic and cultural affiliation was with Greeks from Lesbos.

Demetrius of Scepsis, however, had concluded that the Troy of his time was an impostor and that the real Troy lay some stadia distant. In reaching this opinion he was supported by the researches of a woman called Hestiaea of Alexandria, who had studied the soil around ‘New Troy’ and judged that it had once been a marsh or lagoon and therefore would have been far too soggy for anyone to wage war on. Neither of these treatises survived antiquity but they were picked up by Strabo, whose many books of geographika did survive. As a result, when Europeans came looking for ancient Troy in the 19th century they had good reasons for doubting that the place now known as Hisarlik, although identified as Troy on coins and inscriptions, was the same city Homer described.

Not everyone was put off by Strabo’s arguments. In 1822 Charles Maclaren published A Dissertation on the Topography of the Plain of Troy, in which he derided ‘those refined ages when men began to question every thing from pure wantonness of speculation, and love of paradox’. ‘Surrounded as Alexander was with men of learning,’ Maclaren wrote, ‘it is not likely that he would have stopped in his career of war to bestow his money and his cares upon New Ilium, had any good reasons been then known for believing that it occupied a different site from the ancient city, for which alone his favours were designed.’

Maclaren was mostly ignored, but in 1847 he travelled to the region and met up with Frank Calvert, an amateur archaeologist whose family owned more than two thousand acres of farmland on the edge of the city, including part of Mount Hisarlik. Scepticism and the outbreak of the Crimean War inhibited excavation, however, and it was not until 1863 that Calvert started digging at New Troy, requesting the sum of £100 from the British Museum to help fund the project. The money was not forthcoming, and it was probably with some relief that he found a collaborator-cum-rival in the German businessman Heinrich Schliemann, who had made a fortune in gold dust and indigo. Schliemann began digging in 1870 and immediately stumbled across the remains of a substantial building he believed to be Priam’s palace. Three years later he struck gold, or what he called ‘Priam’s Treasure’: 137 metal objects, including two gold cups, five necklaces, earrings and a headpiece, excavated personally by Schliemann and his wife, or so he claimed, while the Turkish workers were sent on a hasty lunch break.

The pieces were smuggled out of Turkey and put on display in Berlin in 1881; in 1945 they were removed to Moscow, where they remain. Their absence from the section of the exhibition devoted to the real Troy leaves it lacking in lustre, but enough of his other finds have been lent to enable the curators to lay out every stratum of Schliemann’s Troy (some of the artefacts from Berlin were permanently blackened by the Allied bombardment). We now understand that Schliemann dug right through the Troy of the Greek imagination, the late Bronze Age city today called Troy VII, which would have dated from around 1500-1300 bc (the period described by Homer). His treasure derives from a Troy well beyond imagining, Troy II, now dated to the third quarter of the third millennium bc, more than a thousand years earlier.

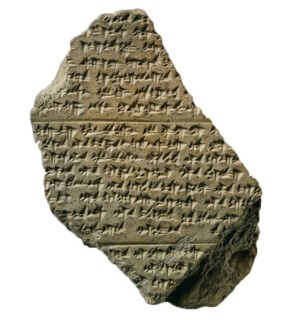

Schliemann himself was disappointed by the apparent size of the city he found. The citadel of Troy II was around one hundred metres in diameter. The catalogue, as beautifully put together as the exhibition, devotes ten pages to the question ‘Did the Trojan War happen?’ It’s hard to know what a positive answer might look like. On the level of nomenclature, most people are convinced that a reference in Hittite documents to ‘Wilusa’ is a reference to the place known to Alexander as Ilion. The name ‘Alexander’ is itself Trojan – it was an alternative name for Paris – and ‘Alaksandu of Wilusa’ is also mentioned in a Hittite document. The city was contemporaneous with Greek Mycenae and relations may not always have been friendly.

But if Homer was dealing with memories of real historical facts how could he have missed so many much bigger facts about the world of Troy VII, not least the existence of the mighty Hittites themselves? Perhaps all we can say is that in the time of Homer there were some huge ancient walls still visible on Mount Hisarlik and no other candidates in the area on which to hang an epic.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.