My parents were militantly radical Dubliners working in Belfast when their first-born – me – came along. My mother, Celia, was vivacious, highly strung, something of an actress, both metaphorically and literally: she had had a brief career with the Unity Theatre in Euston and played the part of Ethel Rosenberg in a play whose title and author I can’t remember. She also – or so she told us – was once invited by Charlie Chaplin to audition for a small part in City Lights, and thereafter was often to be heard humming the ‘Limelight’ theme tune in memory of the chance she declined or was unable to take (the invitation came when her marriage was falling apart). My father, Jim, was a hard-drinking raconteur, the best I have ever known, who could reduce an audience to tears (from laughter) and drive them crazy with an art of detour and digression that would have them on tenterhooks for the climax of his narrative. Never happier than when down the pub, he was completely unsuited to domestic life.

After his separation from my mother, Jim spent many years in a semi-vagabond wilderness, ‘home’ a cupboard of a room in pre-gentrified Tufnell Park. He remarried in 1958 and I went to live with him and my stepmother, Mollie, during my holidays from boarding school. A year later, after a series of infractions, I was expelled from school, and moved in permanently until I left for university. On marrying him, Mollie had some idea of what she was taking on, but while she remained loyal and supportive to the end, his drinking habits drove her to despair. When I joined them, one of my jobs was to fetch him from the pub. This was a task that demanded not taking no for an answer, with the result that as a teenager I acquired an absurdly fearsome reputation among some of the toughest drinking men of working-class London, though of course I, as messenger, was only the medium through which deference was shown to Mollie, whose hospitality towards assorted wandering Irish, British and Polish souls was legendary. The parties would often go on until the small hours, usually ending with a round of Irish rebel songs, lead by the melodious tenor of Sean Malarkey, a shy man who had to be prevailed on to sing. One night he regaled us with an anti-colonial number that included the line ‘Out, out, ye Saxon dogs’. An Englishman called Don Griffin, who, like my father at the time, worked as a guard for British Rail, took offence. Out the Saxon dog went and off down the high street, with my father in hot pursuit, and me in hot pursuit of my father. At the end of the street there was a cemetery. Don leapt over the wall, my father followed, with me bringing up the rear, all chasing one another like ghosts among the gravestones.

His luck finally ran out, however. Coming home one evening seriously the worse for wear, he slipped on the front steps, fell backwards and cracked his skull on the paving. He went immediately into a coma and, after two weeks on the life-support machine, the doctors gently told me that the case was almost certainly hopeless and asked if we would agree to the machine being switched off. Mollie, distraught beyond description, left the decision to me. I hope never to be confronted with another like it. There was a degree of mystery as to the cause of his accident. The most likely explanation was loss of control while tanked. But there had also been a recent history of occasional blackouts, for which the only explanation the doctors could come up was that they were a delayed consequence of being shot in the side as a young man in the Spanish Civil War. I was always called ‘Kit’, after Kit Conway who died fighting alongside my father in the Battle of Jarama.

My father’s death secured him not one but two funerals. The first took place in London, starting with a procession of friends, colleagues and banners before we made our way to Golders Green crematorium, the keynote speech given by Mick O’Riordan, then general secretary of the Irish Communist Party. The second took place some months later in Dublin, where I took his ashes to be buried in a plot of unconsecrated ground in Mount Pleasant cemetery belonging to the Gannon family. Bill Gannon, many years my father’s senior, had been weaned by my father from his allegiances as an IRA gunman to the cause of revolutionary Marxism. When Bill died, the Gannon sons invited Jim to be the impresario of the funeral. This he did with great panache, and presided with even greater abandon over a protracted wake. The local boys thought it was getting out of hand, and so frog-marched him to the port to catch the night-boat to Holyhead. Jim cunningly gave them the slip, their relief at imagining him safely far from Irish shores shattered by consternation at later finding him ensconced in a Dublin pub, grinning over his pint of Guinness. He returned to London wrecked, but with an idea lodged in his head that never left him, though it was to be expressed only intermittently, and more than a little sentimentally, when he was in his cups: ‘When I go I want to be buried alongside Bill.’ He’d put this request to Bill’s sons at the wake and they had offered him the resting place he apparently desired.

When he died it seemed best, or right, to take his wish at face value. And so, after myriad preparations, off I went to Dublin. I was ill at the time and have only hazy memories of the funeral. But there were hundreds of mourners. I recall a gun salute (probably by Officials, though my father was never a member of the IRA and heartily loathed the Provisionals). There were speeches (I don’t remember by whom). And then I placed Jim’s ashes in the grave of Bill Gannon. But something else I don’t remember – a detail that was to have some material relevance – is whether I put the urn into the grave or emptied the ashes from the urn into it.

The funeral was succeeded by a two-day wake. I had a fever, but somehow managed to keep a grip on one of the more important topics of conversation: what to inscribe on the headstone? Bill Gannon and his dates were already there, so there wasn’t a great deal of space. There would be Jim’s name and dates of course, but there had also to be something else to signify and summarise a life. The conversations yielded seven candidates: Patriot, Trade Unionist, International Brigader, Anti-Fascist, Marxist, Socialist, Communist. There was room for two, at most three. We spent what seemed like an eternity chewing this particular cud, naturally without even a shadow of consensus. I thus returned to London with an issue to put before Mollie. She sensibly argued that the rational solution would be to plump for just one. But which? ‘It has to be “Communist”,’ Mollie said. ‘It’s what makes sense of all the others.’ Some months later I returned to Mount Pleasant with instructions for the stonemason. Doubtless a good Catholic, he didn’t so much as blink when I asked him to chisel: ‘Jim Prendergast, Communist. 1914-1974.’ I went back the next day and the job was done. I paid the mason his 70 quid, then set off back to London.

Years later, on a trip to Ireland with Wynne Godley, I asked him to accompany me to the cemetery to pay my respects. Mount Pleasant is a maze and, while I thought I could remember where the grave was, I couldn’t. Wynne – an exemplary companion – and I spent hours roaming the labyrinth, wandering in and out of overgrown plots, stumbling over headstones. In the end I found the grave, but was stunned also to find that my father’s inscription had been erased, in its place the name and dates of Bill Gannon’s sister, who had died in Dublin not long before.

I couldn’t believe that this had been allowed to happen without our knowledge or consent. I high-tailed it to the mason’s office. He remembered me instantly and, red-faced, explained that the immediate family of Bill Gannon’s sister had ordered it, and that, since the plot belonged to the Gannons, there was nothing he could do but obey. There was nothing much I could do either: the branch of the Gannon family that Jim knew were radicals who lived in England, the Dublin branch was devoutly Catholic (the former knew nothing of what the latter had done). One of my Dublin cousins came up with a generous suggestion. His father, Tom O’Brien, an erstwhile comrade-in-arms, was also buried in Mount Pleasant. Tom’s wife, Ann, my mother’s sister, still very much alive, was Jewish and had declared her intention of being buried in the Jewish cemetery. There would therefore be no impediment to my father’s remains joining Tom’s. The problem, however, concerned the condition of the remains. For it was not just a question of the bureaucratic hassle of applying to open up two graves, but also the impossibility of my remembering whether what I had deposited was the urn or the ashes poured from the urn. Could I reasonably apply for the opening of a grave inside which the earth might have absorbed all trace of my father’s mortal frame? I still have not been able to deal with this issue. What is left of Jim Prendergast, Communist now lies in an unmarked grave.

Jim left school at 13. His first political act was to join a Blue Shirts march which he mistook for a workers’ demonstration. It was not a mistake he made again, becoming one of the founder members of the Irish Communist Party. He would tell the tale of the day they moved into party headquarters: a mob of Catholics, incensed by stories of the Communists hanging pictures of the Virgin Mary upside down and using images of Jesus Christ as doormats, gathered outside and started to smash the place up. The comrades escaped across the rooftops, Jim falling through a glass roof, his left leg scarred for life as ‘proof’ of this adventure. Perhaps it was a tall tale, not untouched by blarney. In the 1960s the BBC series One Pair of Eyes devoted a programme to Claud Cockburn. There is a sequence in which Claud and Jim stroll down the street, and Claud remarks: ‘Jim, do you remember that time we were having a drink with Hemingway in a bar in Madrid and a Fascist bomb came through the ceiling?’ Quick on the uptake, my father elaborated (never having met Hemingway in Madrid or anywhere else).

Being a founder member of the Irish Communist Party was not likely to commend itself to most of Jim’s family, although some of them were drawn to, and even active in, the nationalist cause. The Prendergasts came from Cork, at some point migrating to Dublin slumland. Patrick, my grandfather, married Mary Leonard. Her mother, Granny Leonard, I saw once, at a very great age, wizened and swaddled in a large armchair, surrounded by clan members. She was very small and a republican firebrand. During the uprising, she would apparently don her toque, wander down to a British-manned police station and lob in a bomb. She would return half an hour later, a small, respectably dressed woman, to survey with grim satisfaction the carnage she had inflicted on the colonials. Granny Prendergast (my paternal great-grandmother) endured horrors of poverty. She would put aside pennies from the house-keeping and when she had sufficient funds stashed away would take herself off to get comprehensively plastered. She had to be brought home in a cart. As for my grandfather, he had been a champion swimmer. One fine summer’s day, a gust of wind blew his new trilby into the Liffey while he was crossing O’Connell Bridge. He went down to the quayside, stripped to the waist and plunged in never to reappear; it seems that he dived too deep, an ice-cold current stopping his heart. His wife, Mary, I knew much better, a gentle, unassuming person, resigned, in that passively uncomplaining way so common among Irish women of that time, to hopeless poverty. Like the rest of the family, or at least the women, she was also piously if non-dogmatically Catholic.

My father broke away from that Catholic legacy, and his marriage to Celia Sevitt was part of this. The Sevitts (originally Zhevitovsky) came out of the Ukrainian shtetl. My maternal grandfather, Abram, who spoke several languages (Yiddish, Russian, German, English, French, with smatterings of Turkish and Arabic), left Ukraine to escape conscription into the tsar’s army and made his way hair-raisingly across Europe to end up in Liverpool. His wife, Elizabeth, no less enterprising, left Ukraine in search of work, also ending up in Liverpool, which is where they met and married. The plan was to emigrate to New York, going by way of Dublin, but when they got to Dublin they decided to settle there. I never knew Abram, who died before I was born, but after we had moved to England, I spent many summers at Elizabeth’s house on the South Circular. On Saturdays I accompanied her to synagogue; Sundays I went with my paternal grandmother to Catholic mass, bewildering experiences for a child from a committedly atheist family.

Abram and Elizabeth had seven children: Julie, Millie, Jay, Celia, Ann, Simon and Benny. Julie and Millie married ‘in’, their respective husbands, Harry and Sid, being successful businessmen in the clothing trade. Harry was a bit of a wide-boy, with a billiard table in the front room. He got mixed up in some shady business during the war, smuggling contraband silk stockings from Ireland to England. It was rumoured that he had been caught and served time. Sid was dapper, always in an expensive suit. He opened two factories in Leeds, where we emigrated in 1947 (Sid gave my father a job). But he got into financial trouble and burned the factories down on an insurance scam. It seems he was rumbled and had to get out fast, leaving with Millie for Australia, never to be heard from again. Some years later, Harry and Julie followed them to Australia, and so did Jay. Simon became a distinguished scientist. Benny, the youngest, was a good-natured wastrel, who never married (there were dark hints that he was gay) nor held a proper job. He lived for the most part on the fringes of the theatrical world, dreaming of becoming the next Sean O’Casey or Samuel Beckett.

Ann Sevitt’s engagement to Tom O’Brien produced strains within the family, but were as nothing compared to the firestorm generated by Celia’s engagement to Jim Prendergast. Celia persuaded Elizabeth to throw an engagement party at the house. Jim showed up late, with a pal and a crate of beer. They installed themselves in the kitchen and spent the whole evening polishing off the contents of the crate, while the rest of the party sat in the ‘drawing-room’. Jim maintained that he was protesting against the aspirations of Celia’s family to petty-bourgeois gentility. Elizabeth never forgave him, and it marked Celia’s defection as not just an error but a disaster. But defect Celia was determined to do, not only because she was in love with Jim, but also because she was in love with radical politics, part of the meaning of which was to break with religion.

My birth truly put the cat among the pigeons. ‘Jim, I think we have to have Kit circumcised.’ ‘What? Why?’ ‘Mother will hit the roof if he isn’t.’ Celia could have finessed the issue by means of the eminently secular hygiene argument, but that road was not taken. For Jim, placating Elizabeth and thus propitiating the false gods of religion was out of the question. He was adamant, Celia was adamant, like two tankers about to collide. Jim then did what he so often did when at the sharp end of an intractable marital dispute: steer the tanker to wet dock. He absconded on a three-day bender. On the third day he ends up sitting at a bar, staring morosely into his glass. In walks a friend, Billy McCullough. ‘Christ, Jim, you look dreadful.’ Jim narrates his woes. Billy’s face lights up: ‘No problem, no problem at all.’ Jim perks up, all ears. ‘I know a Communist rabbi.’ Smiles all round, the interests of every party catered for, time for celebration. ‘What’ll you be having, Billy?’

Unlike some of his middle-class comrades my father never played the part of proselytiser to me. He left me to find my own way. While I sympathised (and still sympathise) with many of his political beliefs, I never shared his formal political affiliations. One thing I am sure of, however, is that any fully constituted Communist regime (‘actually existing socialism’) would have given him a very hard time and that, in his own small way, he would have given it a hard time. I am not sure what his reaction to Philip Roth’s I Married a Communist would have been. He would doubtless have admired the dedication of Roth’s ‘pure’ Communist, O’Day, but it is to Ira Ringold that my father would have instinctively warmed – to what Roth describes as ‘the sanity of an expansive, disorderly existence’. Jim seems to have been wired for just such an existence. The stories are legion. Most are connected to drink, and many to brushes with the law. There was the visit to Barcelona during the dying days of the dictatorship, when he was hauled off for interrogation by the Guardia Civil having staggered along the Ramblas shouting ‘down with Franco!’ And then in Moscow, as part of a delegation from the National Union of Railwaymen, he managed to slip away on the last evening, ending up in a bar where he met a bunch of high-spiritedly dissident students, in whose company he set off on a vodka razzle. He was arrested, jailed for the night, his passport taken, returnable only on payment of a fine. He refused to pay. When argument either from status (the delegate) or from fraternity (the Communist) cut no ice, he tried the even stranger tack of a lecture on the ‘bourgeois’ theme of human rights, especially the right to drink as much vodka as he pleased. The stony-faced police officers remained impervious to these brazenly opportunistic representations: pay the fine and you’re out, don’t pay it and you stay here. Only with the arrival of Mollie, who settled the fine forthwith – to my father’s fury, he having decided to ‘take a stand’ despite the fact that the plane for London left that afternoon – was the dilemma resolved. I often wonder if there is a mouldering file somewhere in the Moscow archives marking my father down as ‘unreliable’.

Among the few memorabilia still in my possession is a framed document from the Inner London Quarter Sessions: ‘take notice that upon your conviction for “Threatening to murder”, this court has this 20th day of March 1969 made an order discharging you, subject to the condition that you commit no offence during the period of 12 months now next ensuing.’ The man my father threatened to murder was Georges Bidault. Jim always claimed it was Benny’s fault. Benny, Celia’s brother, had turned up in London while Mollie was away, and rang to ask if he could stay a couple of nights. Although a kindly soul, Benny managed to combine virtual pennilessness with the manner of a sensitively languid would-be playwright, dwelling incessantly on the finer points of the latest Abbey Theatre productions. Coming home from work started to become a dread-laden ordeal. There was only one solution: not to come home until well-cushioned with a pre-prandial intake. Thus it was that around ten days into Benny’s visit, Jim rolls home in the early evening, beer-buttressed but fuming. On his way he’s picked up a copy of the Evening Standard; the front-page headline is ‘De Gaulle pardons Bidault’ (Bidault having been imprisoned for his part in the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète at the time of the Algerian War). Outraged, Jim nods cursorily to Benny, sits down at his desk and writes the following letter (on union notepaper): ‘Dear Mr Bidault, If we were in Dublin, three of us would drive up into the Wicklow mountains, and only two of us would come back down. Yours, James Prendergast.’ He puts this into an envelope addressed ‘Mr Georges Bidault, Paris, France’, and pops it in the post.

A few days later (Benny now departed), there is a knock at the door. My father, alone in the flat, opens the door. A Special Branch officer asks him if he is James Prendergast and if he wrote the letter the officer shows him. ‘Yes, I am and I did,’ Jim replies. ‘In which case, Mr Prendergast, I’m afraid you’re under arrest for threatening to assassinate a figure in French public life.’ Jim is taken to the police station, charged and remanded on bail. The trial had its priceless moments. While we waited at the Old Bailey before being ushered into the courtroom, Jim announced he needed to go to the gents. When, a quarter of an hour or so later, he hadn’t returned, we went looking for him. He wasn’t in the gents, wasn’t in fact anywhere on the premises. The penny drops and out we rush to the nearest pub, where we find him seated at the bar downing a pint. ‘Nerves,’ he explains sheepishly, ‘nerves.’ We drag him back just in time. Perhaps anticipating a defence argument that the contents of the letter did not constitute an execution threat, the prosecution tried the line that, as a pig-ignorant Irishman, my father might be unaware of the full meaning of the words he wrote. At which point, Jim turned to the bench and declared: ‘Your Honour, like Oliver Goldsmith, Dean Swift, Edmund Burke, Oscar Wilde, William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, John Millington Synge, Sean O’Casey, James Joyce, Brendan Behan and Samuel Beckett, I occasionally have difficulties with the English language.’ Peals of laughter around the courtroom, even the judge working overtime to suppress a smile. Perhaps, in the circumstances, not the best line of defence, but a memorable short course in the history of modern ‘English’ literature. My father got a conditional discharge.

There was also his one foray into English electoral politics (outside the union) in the late 1950s. For the London local elections he was persuaded to stand as a Communist candidate in the borough of Westminster. Although this was rich man’s territory, there were still pockets of militant working-class life on the council estates. For those disinclined to vote for any of the other non-Tory candidates, here was a chance to register a symbolic protest. On the night his election address went to the printers, we got a call. Jim had forgotten to include a photo. Mild panic but in theory no big deal: just a matter of catching the Tube to the nearest known photo booth, at Marylebone Station, and then taking the photo round to the printer’s shop. But, as so often with Jim, what was true in theory translated into practice only with superhuman difficulty. He was so roaring drunk he could scarcely stand. I and a schoolfriend who happened to be staying with us propped him up and wheeled him off. There were many mishaps. The most dramatic occurred as we stood on the escalator at Tufnell Park, my friend positioned in front of my father, I behind grasping him by the collar of his coat. To no avail. Jim lurched forwards, I lost my grip and all in front of him tumbled down the escalator concertina-style. Happily, no one was hurt. From there, by the expedient of treating him as the amiable corpse he in effect was, we made it to Marylebone. The photo redeemed the whole misadventure. To anyone in the know, the smile was the bleery one induced by an alcoholic stupor and the drooping eyelids the reflex of falling asleep. To the uninitiated, however, the smile was seductively benign and the hooded eyes the sign of a deep political wisdom, the mugshot of the warmer sort of Communist. He got a few hundred votes, some perhaps because of the photo.

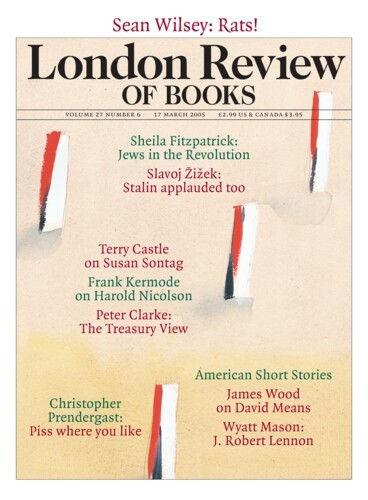

But there was worse – surely I mean better? – to come. On the eve of election day, Jim had the perfect excuse: he had to have a drink (or ten) with his mates to calm his agitated nerves (those nerves again). This time the ever-merciful Mollie decided to let the rope out and so I was relieved of my rescue duties. On his way home after closing time he needed to relieve himself. Normally this was a routine matter, dealt with in appropriately discreet ways. But tonight was not routine; tonight was the antechamber of an assault on the System. Buoyed by exhilaration and defiance, he wandered out into the middle of the road, cars whizzing past in both directions, and proceeded to spray the symbols of capitalism with the people’s urine. Unfortunately a bobby on the beat came along as his contempt poured forth, arrested him for being drunk and disorderly, and carted him off to the local nick, where he was incarcerated for the night to sleep it off. Much to his surprise – the police not being known for their Communist sympathies – when he explained that he was a candidate in the next day’s election, they let him go. At breakfast he filled us in on the events of the previous night, Mollie clucking, I moralistically admonishing, he chuckling through his hangover. On my way to school down Lisson Grove I passed a large stretch of normally vacant wall. It was not vacant that morning. Some joker had come out in the middle of the night and armed with a brush and a can of whitewash had painted in capitals on the wall: ‘vote for prendergast and piss where you like.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.