In the early 1950s I was awakened by the photographs of Walker Evans and the movies of John Ford, especially Grapes of Wrath where the poor ‘Okies’ go to California with mattresses on their cars rather than stay in Oklahoma and starve. I faced a sort of black-and-white cinematic identity crisis myself in this respect … a little like trading dust for oranges. On the way to California I discovered the importance of gas stations. They are like trees because they are there.

In telling this story, ex-Okie Ed Ruscha offers several clues to his enigmatic art: a style that partakes of both documentary photographs and Hollywood yarns; an identity stamped by such images, too; a sensibility that, equal parts Midwest straight and California slick (dust and oranges), regards the weird vernacular of postwar America as totally natural (gas stations as trees); and an inaugural move to LA, not New York, let alone Europe. (Ruscha did travel to Europe in 1961, at the age of 23, only to return with photos which suggest that Paris really is in Texas.) He is a singular artist, at once folk, Conceptual and Pop, an unlikely son of Edward Hopper, Marcel Duchamp and James Dean. Two retrospectives – a small show of photographs, a large one of drawings – are at the Whitney Museum until 26 September (the drawings will travel to Washington and LA over the next year); a collection of notes and interviews, Leave Any Information at the Signal, was recently published, too.*

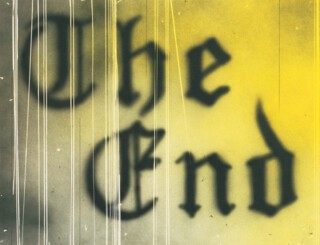

Trained like some Pop artists in commercial design, Ruscha worked early in LA on ads, book covers and magazine layouts (including Artforum from 1965 to 1967). While other Pops used only fragments of print sources, Ruscha brought an entire graphic look to his early paintings, which juxtapose abstract fields of colour with appropriated fonts from consumer products and comic books. Bringing together alien visual cultures was a characteristic Pop move, and Ruscha made it look easy. As the curator Margit Rowell argues in the catalogue,† he also reworked drawing, usually a personal form, through the impersonal medium of photography: his marks, often applied in gunpowder with Q-tips, are super-precise, and his words, at once odd and everyday, unfold in the deep spaces of his misty colours like so many liquid ribbons or elliptical credits at the end of a movie. In his procedure, however, there is no such immediacy: ‘Abstract Expressionism collapsed the whole art process into one act,’ Ruscha has remarked (he is one of the last generation of art students who had to confront this beast). ‘I wanted to break it into stages, which is what I do now.’

All of his work is premeditated, especially the cult photo-books, which, in good Warholian fashion, are as advertised: Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1967), Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass (1968), Real Estate Opportunities (1970) and so on. ‘I don’t even look at it as photography,’ Ruscha has said, ‘they’re just images to fill a book,’ the parameters of which are set beforehand. Several books survey typical spaces of LA, and the presentation is as ‘neuter gender’ as possible: ‘They’re a collection of "facts” . . . a collection of "readymades".’ Like many Duchampian artists from Jasper Johns (an early influence) to Gerhard Richter, Ruscha has dampened his art in a way that nonetheless allows it to be distinctive: a deadpan-ness – funny, desolate, sometimes both – is conveyed in his homely shots of solitary gas stations or aerial images of empty parking lots; and the apparently arbitrary numbers (why nine pools?) only add to the blank absurdity.

Despite the studied moves, a vague ambiguity emerges from many works, a flat enigma that Ruscha calls ‘a kind of "huh?”’ (here again one feels the connection to Johns). Often it stems from his words, which, as in a misspelled grocery sign or an onomatopoeic utterance (‘Oof’, ‘Ding’), appear both everyday and incorrect. Yet, like Magritte (he was once called ‘the Magritte of the American Highway’), Ruscha can also produce this noise through his images alone. And, when juxtaposed, his words and images do not often support one another, but stand apart or are even antagonistic, in crossings that cross up the viewer as well. Frequently the words are suspended in sense as they are in space (one reason Ruscha likes to depict them is that they ‘exist in a world of no size’). More than once he has borrowed Claudius’s ‘words without thoughts never to heaven go.’ It could be his motto. (There might be an allegory of American political speech here, too – faux-sincere and false-populist – as practised, for example, by our gifted president.)

This interest in odd words began as an appreciation of common things: the early Ruscha focused on products such as Spam and Sun-Maid Raisins. Warhol once suggested ‘Commonist’ as a substitute for ‘Pop’, as if a collective might still be wrested from consumerism, and the common in Ruscha hesitates between the folk and the Pop – certainly he came to it at a time when it was getting ever more commodified. Like other Pop artists, he also plays with reified language, with slogans and jingles: drawn to terms on the threshold of cliché, he sometimes pulls them back via ambiguity, and sometimes pushes them over, once and for all, into the status of brand or logo (early on he depicted such trademarks as ‘Standard’ and ‘20th Century Fox’). Occasionally, too, he underscores the paradoxical animation that such fetish-terms can possess, presenting them keyed up like special effects, as if they were the only public figures left to portray, the truly dominant features of the landscape (the Hollywood sign that presides over the city is another element in his work). Finally, in some photo-books Ruscha renders landscape as so much real estate, gridded and numbered as such: Some Los Angeles Apartments, Every Building on the Sunset Strip.

For Ruscha, ‘Los Angeles is like a series of storefront planes that are all vertical from the street,’ and this flat frontality is reflected everywhere in his art. His city is one of billboards, too, and his paintings in particular evoke these giant screens suspended in the landscape. This dual focus on storefronts and billboards implies an automotive point of view, and the windscreen is indeed the unseen frame of many of his pictures, especially those of signs captured at different scales amid broad horizons and vast skies. Just as important is the design culture of LA: more than one of his images announces that ‘Hollywood is a Verb.’ ‘They do it with automobiles,’ Ruscha adds, ‘they do it with everything that we manufacture.’ Of course, ‘they do it’ with movies above all, and he also evokes the ‘celluloid gloss’ and panoramic expanse of cinema. At once deep and flat, space in movies is all surface, and vice versa, and words (again as in credits) appear in the same register as images. Ruscha often intimates the filmic screen of projected light, which he calls a ‘deeply Californian version of infinity’.

‘Close your eyes and what does it mean, visually?’ Ruscha asks about this Hollywood Sublime. ‘It means a way of light.’ As he processes it in his pictures, this light is true and illusory at once, the hallucinated (or medicated) stuff of Hollywood dreams that offers a ‘feeling of concrete immortality’. At the same time, Ruscha presents this dream-space as thin and fragile (one of his keyed-up sunsets contains the words ‘eternal amnesia’ in small print at the bottom), and sometimes there is a hint of catastrophe, a sick glow beyond the usual smog, a touch of Nathanael West or Joan Didion. Though he is a believer to the end, Ruscha suggests that Los Angeles might be a mirage and California a myth – a façade about to crumble into the desert, a set about to liquefy into the sea.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.