After 23 hours in the air, I got off the plane at Christchurch, New Zealand to be informed by the walls in the airport that I was in Middle Earth. I was groggy enough not to care where I was, so long as I was somewhere (actually I still wasn’t; only in transit to Wellington on the other island). I was sick with lack of sleep, lagging a day ahead of myself, and Middle Earth seemed as likely a place to be as anywhere. Time travel had to be involved, though, because Middle Earth was, as I knew it for a few moments in 1969, somewhere in Notting Hill, I think, and was a place for the ingesting of quantities of hallucinogens, watching the recombinatory adventures of hot coloured oils projected onto screens all around and listening to the pixilated lutes and whines of the Incredible String Band. I’d have preferred to be on the moon, the Sea of Tranquillity, say, which seemed just as probable, but I have learned that passive acceptance of life or death is the only way to survive long-haul jet travel. It took a few moments for me to remember I was in New Zealand and that the dreary sourcebook of my drug-crazed hippie nights had been filmed there and won a regiment of Oscars. There being only about three and a half million people in the country, everyone had either been in it (there were calls for extras, apparently, that invited only those over 6'7"; or under four feet to apply) or been inconvenienced by it, so it was a cause of great national pride. It’s not for me to judge.

Hardly surprising that the people of New Zealand should have embraced their reassignment to Middle Earth: there can’t be a population in the world who feel themselves to be so peripheral. Everyone explains how far away they are. ‘We’re so far away,’ people keep telling you apologetically.

‘Far away from what?’ you ask, alarmed, because they and you are both here, so far as it is possible to tell.

‘Everything.’

In fact, of course, everything is far away from New Zealand if that is where you are. But that’s easy to say if you are merely in transit and you have a return ticket to the far away you came from. All New Zealanders tell you about their European trip, a year or five spent where far away isn’t. Or they say that they are planning such a trip – soon or one day. The feeling of separation grabs you, and you rapidly begin to think like a New Zealander. I’ve never felt the distance of distance so strongly. Not in the Antarctic, not at the tip of Tierra del Fuego, not even in the nowhere of Raton, New Mexico. Only in the grip of a depression have I felt the ‘world’, whatever I and my New Zealand hosts meant by that, to be so remote.

‘Have you noticed that everyone wants to be loved?’

I had noticed.

‘Well, there you are. You see?’

I didn’t, though I knew what was coming next. Silvie T. was driving me from her 500-acre deer farm on the Coromandel coast to catch my bus to Auckland. I had stayed three still, solitary days in one of the half-dozen wooden cabins they rent out to tourists. It was the fag end of the season and I’d been the only customer. I spent the time on a wooden jetty on a pond that took fifteen minutes to walk around and sitting on my porch watching the oyster-bed nets appear and disappear in the bay below as the tide came and went. A perfect antidote to spending eight days in a hotel with 15 internationally jet-lagged writers (at four in the morning there were queues to get to the email machine in the lobby, each of us probably convinced, as I was, that masterpieces were being sent by the others across the web to important editors, whereas I was just emailing over and over: ‘God, I’m so tired, I want to go to sleep’). This farm-stay wasn’t a hotel. Only accommodation with a kitchenette was provided. Silvie’s husband, a Swiss German who had followed her back from her European tour, had met me from the bus and showed me where to buy bread, cheese and tea. No one interrupted my silence. But now, Silvie had the twenty minutes it took to get to the Coromandel Township bus stop to prove the existence of God to me.

‘Everyone wants to be loved and that shows us God exists.’

‘How?’ This was a bit listless. Three days on my own made me reluctant to engage in theological debate.

‘Because that longing for love is every one of us wanting to let God into our lives. We want God to love us and to love God, but the evil in us stops us from opening ourselves to Him. Do you understand?’ She glanced at me to see if the penny had dropped.

I might have mentioned Freud or Melanie Klein. Or the terrible isolation of the self-aware individual and the horror of the certainty of absolute extinction. Or false consciousness. But I said: ‘Oh.’ I said it as weakly as I could, trying not to imply either that her reasoning had cleared the mists in my mind to revelation, or that I was the devil’s messenger and intent on souring innocent faith with ugly doubt. I just said ‘Oh’ in a mild, non-committal sort of way in the hope that it would do and we could get on to talk about deer farming.

‘Do you see what it means? It means we all know the truth of God. That He exists. It’s only being born evil that puts a barrier between us and Him.’

Silvie had four children. I was suddenly engaged.

‘When your kids were born, did you look at them and think they were evil?’

She was well up on this sort of undermining talk.

‘You have to teach children to be good. You never have to teach them to be bad. They already know how to do that,’ she said triumphantly.

I let nature and nurture pass, but could not quite let the natal moment go.

‘But the first time you saw them, the moment they were born, did they strike you as evil?’

Silvie did not exactly answer this question. She continued doggedly to insist that we were all born to sin. It is clear in the Bible if only I took the trouble to read it. We were, every one of us, wicked from birth and had to learn how to be good.

‘How to be social,’ I muttered, getting a little sullen now.

‘God gave the rules. He called them the Ten Commandments. We aren’t complete until we let Him into our life.’

Silvie had been sinful, she told me, as sinful as they come. But when she came back from Europe, God had come into her life, and she thanked Him every minute of every day for saving her. Her Swiss boyfriend had turned up in New Zealand, doubtless for more sinning, but seeing the remarkable change wrought in her by God had adopted the Lord himself. And life was good. They lived, I had to concede, in what seemed very like paradise: Silvie, her husband, their four children, their blind dog, on their beautiful deer farm, with intensely green rolling hills on which deer grazed next to a swathe of wild uncleared bush above the turquoise sea, and silence, apart from their parrot. On the other hand, there seems to be no part of rural New Zealand that isn’t breathtakingly beautiful, so perhaps what is necessary for a paradisal existence is not so much to let God into your life as to want it enough to stay in New Zealand and hang the distance to – or from – everywhere else.

On the way to Auckland, I had to change buses. The café at the bus station was anonymous and bleak, like every bus station in the world, but the far wall was a bit special. It was covered in a mural so naive in execution it made Grandma Moses look like Dürer. It depicted the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse galloping out of the wall (if only the painter had mastered perspective) towards the travel-weary customers sipping their English Breakfast tea and chewing on dismal blueberry muffins, waiting for their connections. The horsemen wore their credentials written on white headbands – conquest, war, famine and death – and they bared their uncannily white teeth to prove they were up to no good. A low shelf at the horses’ hooves was covered with home-printed handouts offering scripture and advice. My favourite had a drawing, done by the artist who had made the mural. A gigantic finger pointed with pencilled rays of power all round it at a tiny sinner, young by the look of it, in jeans and T-shirt, down on one knee, surrounded by pairs of inverted commas to indicate that he was shaking in fear. A speech bubble came from the distraught fellow, saying: ‘But god I thought you didn’t exist!’ Although people waiting for buses are likely to be spiritually very vulnerable, I was the only person who looked at the leaflets. Maybe, in the only urban desolation for miles around, travellers were content to soak up the uncommon plainness of their surroundings. It’s true that after all the hours I’d spent on buses observing the visual glory of New Zealand I found myself beginning to long for a little urban blight.

‘Feel free to take any of those you want,’ the young woman who was making my tea told me. She was young, blonde and tired looking, in a singlet and black see-through blouse. Assuming the place was run by true believers to catch travelling sinners, I asked if they belonged to any particular group.

‘It’s just the boss. He’s 85. He’s passing on what he’s learned about life.’ Her tone was neutral. She didn’t care one way or another. Maybe when I’m 85, I’ll buy a bus station and know by then what it is that I want to pass on.

I was heading for Auckland in order to fly to Queenstown on the South Island. My final destination was Te Anau, in Fiordland, because it was from there that you could take a boat trip around Doubtful Sound. Fiordland, because I like cliffs and water and being on boats; Doubtful Sound, because you would, wouldn’t you? It seemed just the place for me, even before my encounters with true believers. There’s a converse Doubtless Bay up in the north of the North Island. It was too definite for my taste, so I headed down south where things were apparently less certain. But I had a few hours to wait, again, this time for the bus to Te Anau. Not at a bus station, but in Queenstown, which is to those who like to play with gravity what Middle Earth is to lovers of hobbits. The desire to plummet is everywhere evident in New Zealand. People drop off any ledge, bridge, building or mountain they come across. Falling down is institutionalised in New Zealand. Sit at a table at the café here, 182 metres above Auckland, having coffee and gazing at the view below, and a body suddenly drops like a stone outside the window in front of you. There’s a private adrenaline rush to be had just seeing it. Staid and elderly tourists gasp and jump out of their seats, lost for a second in that panic of watching a catastrophe and not knowing what to do. A young woman harnessed to a wire was jumping off a platform two floors above, every fifteen minutes, to encourage the punters. When I went up to the platform to watch her jump, there were two young men with a high-tech winch reading the newspaper, and the girl herself, arriving back for the next jump with Mars bars for everyone, eating one herself, with a blank, bored look on her face. Then she stepped into thin air, helped by one of the men’s feet on her bum, and her face lit up so that the coffee drinkers at the windows below could see what a lot of fun she was having falling 630 feet for 16 seconds at about 46 kph. It was a slow day. No one else jumped, but she dropped off the building five times before I was suddenly overcome with a terrible realisation that I could give the people some money and do the jump myself. Worse, that I should. It was as if there was something in the air, an adrenaline residue perhaps, that edged me towards taking the plunge. Only enormous inner resources prevented me from acting on the impulse.

When I got off the bus from the airport at Queenstown I had looked up to see half a dozen human beings, attached to nothing very much, falling from the sky. In Queenstown you can fall to earth from planes, swing attached to a rope 130 feet high, tumble downhill inside a transparent ball, fly the thermals under a pair of nylon wings, crash over rapids on jet boats or rafts, or drop off anything attached to a rubber line before being bounced back inches off the ground. The first ever commercial bungee jump was set up in New Zealand in 1988 by A.J. Hackett, a visionary who saw that people would pay money to fall from great heights if they could be guaranteed (more or less) to survive. He mass-produced the rush previously sought out only by extreme adrenaline junkies prepared to die for their fix. For most of the history of the world, humankind has tried to get up in the air and stay there. Up was the desired direction. The Babel builders wanted the heavens, not the depths. The big idea of Daedalus was to fly, not to fall. We looked with envy at the birds, not at the nasty mess under the tree that was all that remained of an incautious monkey. Only the desperate jumped from great heights, and they expected to do it only once. Mountains were climbed, apparently, because they were there, not in order to jump off them once you got to the top.

‘Embrace the fear,’ challenges a pamphlet for Nzone, the ultimate jump in Queenstown, a skydive operation, leaving a plane at 15,000 ft. ‘Our goal. Terminal velocity: 200 kph. Achievement doesn’t come sweeter.’ The brochure goes on: ‘Deep in the human consciousness is a pervasive need for a logical universe that makes sense. But the real universe is always one step beyond logic. We do these things. It is something deep within us, the need to feed our voracious appetite for danger and glory. It is the spirit of man.’

You get a certificate after you land. Take the plunge. ‘Be brave,’ the pamphlet whispers to those of us to whom the call of glory is not quite enough, ‘even if you’re not, pretend to be. No one can tell the difference. But the choice is yours. To go through life able to say "yes, I did it,” or to go through life knowing that you had the opportunity, but you turned it down and walked away from becoming the complete person you could have been.’

And, for a nanosecond, there I was again, my heart thumping and wondering if I ought not to, just for the experience, just because I could, because other people had . . . But I decided against it. Once when I was about seven, I was staying in the country and the local boys had rigged a rope with a large knot on the end from the branch of a tree. The branch wasn’t 15,000 ft above the ground but there was a deadly fall. There was not the slightest doubt in my mind that I was obliged to climb up to the branch, sit on the knot and launch myself into the air, to fall and swing or fall off and die. It was necessary not just so that I could be accepted by the local boys, but so that I wouldn’t have to go through the rest of my life knowing I had walked away from becoming the complete person I could have been. I didn’t die. I swung about like a monkey on a liana. It was fun – or such a relief that it felt like fun. But decades on, I’ve discovered a greater thrill and more pervasive satisfaction than ever higher falls or even the certainty of God: I simply walk away from the complete person I could have been and live thrillingly with the vertiginous knowledge of all the opportunities I have turned down to make me the curtailed person I am today. So I climbed onto the bus for Te Anau and the prospect of a cruise through Doubtful Sound without so much as a final glance up at the sky full of falling bodies.

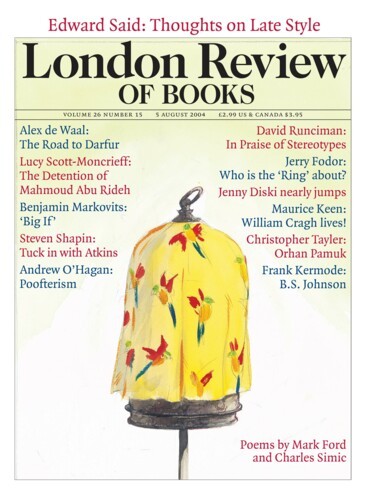

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.