In the summer of 1927, 23-year-old Willy Brandt underwent psychoanalysis in Vienna in an attempt to cure his tuberculosis. He had spent the previous two and a half years in Switzerland, at the Schweizerhof sanatorium in Davos, where, along with the prescribed exposure to sunshine, good food and fresh air, he had undergone surgery to artificially collapse one of his diseased lungs, in the belief that this would give it a better chance to heal. Before that he had spent 22 months at another sanatorium in Ticino, where many of the patients, like Brandt, were German. The spread of TB was one of the legacies of the First World War. As Paul Delany tells us, in Germany TB sufferers doubled in number in the last two years of the war, when ‘soap disappeared completely, and the streetcars were foul with the distinctive stench of famine.’ Rolf Brandt, Willy’s younger brother,

would later talk of having to rummage in dustbins for food and living for a week on one loaf of bread, baked with each day’s portion marked out. All his life he would gobble his meals and leave no scrap on his plate, a typical habit of people who have experienced starvation. Willy did not behave in this way; it seems by the time of the famine his mother was so fearful for his health that she kept up his strength by giving him an extra share from her own rations.

Despite all the evidence, it was still a widely held belief that sufferers brought TB on themselves. Wilhelm Stekel, who treated Brandt in Vienna, maintained that ‘the psychic component plays a formidable part in tuberculosis. Many people become ill because they are tired of life and have a wish to die.’ Whether or not this was true of Brandt, his life since adolescence had not been happy. His father, L.W. Brandt, came from a family of wealthy merchant bankers based in Hamburg; he had been born in London, where his own father had been running the English branch of the company, and was registered as a British subject. This brought complications when war broke out. At first the Brandts supported Germany: Delany’s book includes a photograph taken in September 1914 of the four Brandt boys dressed in miniature German army uniforms; Willy looks slightly rueful. But in November, L.W. Brandt was arrested as an enemy alien and sent to an internment camp. When he was released six months later, he found that his business had suffered and his children had been stigmatised. Willy went to school in Hamburg throughout the war, but in 1919 was sent away to a strict Prussian boarding-school where, his nationality being taken from his father’s, he was registered as a British subject. Over the next few years his academic performance and his health grew steadily worse. He developed asthma. Eventually he fell behind so badly that he was sent to his first sanatorium in 1923. Four years later, the offer of psychoanalysis as a possible cure must have been welcome. When he left the sanatorium in Davos his doctors told him he would be dead within months. He took the risk and arrived at Wilhelm Stekel’s clinic in Vienna in May 1927. Stekel practised what he called the ‘active-analytic’ method, and made much shorter work of psychoanalysis than the Freudians did. As Delany explains, he didn’t ‘sit around while his patients slowly uncovered their subconscious fantasy life. Instead, he . . . plunged straight into the deepest recesses of their psyche.’ Brandt stopped seeing Stekel after three months and never went back. Whether the treatment worked, or whether Brandt simply discovered life for the first time in Vienna, we can’t know, but on his next medical consultation he was found to be free of TB.

Delany has a contradictory attitude towards Stekel. On the one hand, he calls him ‘something of a charlatan’; on the other, he credits him with providing clues to, or even laying the foundations of, Brandt’s particular photographic language, because it was Stekel who introduced Brandt to the symbolism of dreams, and this provided him with a means of expression for his own psychic traumas. In this reading Delany is following Brandt’s earlier critics, David Mellor and Ian Jeffrey, who identified in Brandt’s photographs coded expressions of his disturbed psyche. They contain what Delany identifies as ‘symbols and obsessions peculiar to himself’.

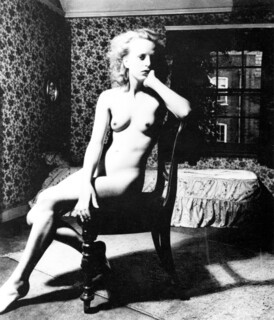

Ever since Brandt became the focus of academic study in the mid-1970s, his photographs have been subjected to readings that claim to identify his neuroses and his sexual obsessions, and find them played out in his subject-matter: his iconic, often melodramatic compositions, his love of high contrast, his predilection for shadows and night-time scenarios, the claustrophobic rooms in which his early nudes were cloistered, even the tunnels and chambers of the London Underground, which, from this critical perspective, represent the underworld of Brandt’s troubled personality. His early life is treated as a source book, consulted for corroborative proof after the ‘secret texts’ of the photographs have been decoded. Faced with a significant lack of hard facts, circumstantial evidence has to bear the critical weight. Delany, following Mellor and Jeffrey, identifies some of these symbols and obsessions. Like them, he traces Brandt’s fascination with English ‘types’ to a favourite book from Brandt’s childhood, Cherry Stones. This was an English picture book which illustrated the figures from English life as they were listed in the popular counting chant: ‘tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, rich man, poor man, plough-boy, thief’ (the beggarman didn’t feature in this version). He finds the frequent appearance in Brandt’s pictures of figures in uniform – servants, policemen, nurses, waitresses – deeply significant. ‘The policeman,’ he writes, ‘was the Freudian superego who kept the dream-world of the city under control.’ The woman in uniform is an expression of his sexual fetishism: ‘Brandt’s passivity towards women could include a positive need for submission, and even to be punished by them.’ Once Brandt begins to photograph nudes, the sexual symbolism is even more overt: his women are acting out private dramas, and the props, which reappeared, not least because Brandt frequently used the same locations, are loaded with significant meanings. A Victorian chair, a lamp, a framed picture of a sailing ship, the bed, all become ‘stock items from Brandt’s erotic inventory’.

To those who think of Brandt primarily as a documentary photographer whose chiaroscuro photographs of the industrial North in the 1930s, or of London during the blackout, established popular images of Britain for the postwar generation, this psychologically charged reading of his pictures will come as something of a surprise. His dramatic (and usefully satanic) pictures of Halifax or Newcastle, of mining families and East End kids, of parlour maids and nippies, have been used so often in subsequent decades to illustrate the social conditions of their time that it has become the predominant idea of Brandt that he was the photographic equivalent of Orwell or J.B. Priestley. Delany successfully shows this reading to be inaccurate, and one of the virtues of his account is the way it traces the evolution of Brandt’s photography as it passes through the various genres, seeing them as experimental stages in the development of a single artistic vision. Even so, the habit of finding hidden meanings in the photographs, then searching the life for evidence to support them, can be a trap for him too. The theories and connections identified by Brandt’s earlier critics presented a challenge to Delany, and sometimes, by his own admission, he isn’t equal to the task. He explains in his introduction that he has had to ‘build a house of straw rather than bricks’, because, for many areas of Brandt’s life, the ‘biographical evidence remains tantalisingly incomplete’. This is particularly evident in the early chapters of his book, when he relies on Buddenbrooks for life among the haute bourgeoisie in prewar Germany and Swiss sanatoria, and Robert Musil’s Young Törless for possible events during Brandt’s schooldays. Where there is no proof, there is supposition. For example: ‘There is ample evidence that Brandt suffered a psychic wound in his school days, something so hurtful that it affected every area of his life afterwards. But just because the hurt was so deep, he utterly refused to explain what it was, even to those closest to him.’ We never learn what the ‘ample evidence’ is (unless it comes from the photographs), and are left, like Delany, ‘guessing at the nature of the trauma’.

Delany, again without much hard evidence, identifies a ‘two mothers’ syndrome in Brandt’s childhood, his love split between his mother and his nanny, which resulted in his ‘obsession with possessing two women at once’. This showed itself in the close relationship between Brandt’s first girlfriend, Lyena Barjansky, and his first wife, Eva Boros; and between Eva and his second wife, Marjorie Beckett (Brandt shared a flat with both Eva and Marjorie from 1938 to 1948). Delany finds more evidence of this fantasy in the photograph Brandt took in 1941 of Robert Graves, Beryl Pritchard (whom Graves would marry in 1950), and another female figure, whom Delany misidentifies as ‘the actress Judy Campbell’, sitting in Graves’s house in Devon. ‘It seems more than likely,’ Delany writes, ‘that Brandt was using this scene to express feelings about his own domestic triangle, in which he adored Marjorie while Eva adored him.’ (The third figure was, in fact, a young German émigrée, Marion Gutmann, who shared friends with Graves, and happened to be visiting him that day.)

Without much in the way of support from private letters or diaries, Delany is left with the photographs: with his uncommunicative subject on one side and the theories of earlier critics on the other. The tension can be felt, for example, when it comes to deciphering one of Brandt’s early nudes. The picture shows a woman naked to the waist sitting at a table, with her arm outstretched and the palm of her hand upturned. The wide-angle lens of the camera has elongated the forearm and enlarged the hand. For Delany, the symbolism of the picture remains ‘enigmatic’, but he suggests that the distortion serves Brandt’s ‘long-standing sexual obsessions’. Mellor goes further, drawing on Lacan for his interpretation. In the outstretched arm he sees, ‘traced out like the enigmatic skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors . . . or Dalí’s soft objects . . . "the phallic ghost . . . the imaged embodiment of . . . castration"’. Brandt himself, talking about the same picture in a film made by the BBC in 1983, said only that ‘it was the camera that produced this effect. The lens distorted everything. I never knew it would happen.’ In the context of the elaborate analysis by his critics, this answer sounds like a rebuke.

The BBC film is shown on a loop as part of the current show at the Victoria & Albert Museum. The exhibition is relatively small but elegant, with works from every period, from the documentary pictures of the 1930s and early 1940s, to the landscapes, portraits and nudes. Brandt thought the nudes were his only artistic works – the rest, he said, were ‘commercial’ – and the show puts the impression that he was a documentarist in its correct perspective: the documentary pictures took up only a decade or so in a career of more than fifty years. The setting at the V&A – tenebrous prints on a dark background in a low-lit gallery – brings out the best in Brandt’s landscapes, particularly the more mystical ones, such as the earthworks at Barbary Castle or Stonehenge in the snow. These are pictures from the landscape of the Romantic imagination, far from the reality of motorways, out-of-town superstores and ‘Logistics’ warehouses.

The film gives a fascinating glimpse of Brandt in the year he died: a slender, elegant man with birdlike features, giving a whispery commentary on his photographs in a voice which Tom Hopkinson, Brandt’s editor at Picture Post, described as ‘as loud as a moth’, and which even in 1983 retained more than a shadow of a German accent. Shuffling through his pictures, Brandt is gentle, polite, obliging, but unforthcoming. The interviewer picks out the well-known photograph of Halifax, taken in 1937, dominated by the silhouette of a tall factory chimney, with, in the foreground, a group of young boys running across cobbles, and says, pointedly: ‘Mr Brandt, this is an enormously composed photograph, isn’t it?’ Brandt delicately sidesteps the insinuation that he had somehow set it up: ‘Yes, I was lucky to have such a good composition. But I didn’t change anything. The boys, when they saw me coming, they came running towards me.’ He talks about Halifax with wonder in his voice. ‘A fantastic town. Absolutely extraordinary. A real dream town. I’d never seen anything like it before.’ Between Vienna and Halifax there was less than a decade. But in that time Brandt changed from being an isolated young man, unsure whether he would live or die, let alone find a profession, into a committed photographer living in London, with a wife and a published book to his name.

In Davos there had been darkrooms and Brandt had owned a camera. But the idea of taking up photography as a profession came from the Viennese society hostess and philanthropist Eugenie Schwarzwald, who was, as Delany describes her, ‘Lady Ottoline Morrell, Beatrice Webb, A.S. Neill and Margot Asquith, all rolled into one’. Schwarzwald surrounded herself with a hand-picked group of youngsters who were invited to spend their holidays in her country house, which she ran like a summer camp. It was at her suggestion that Brandt became apprenticed to a studio photographer, who taught him the basic skills of lighting, composition and retouching. He took photographs in the streets of Vienna and Hamburg, as well as his first formal portraits, again thanks to Schwarzwald, who introduced him to Ezra Pound and Arnold Schoenberg. The Pound picture is usually given a prominent place in Brandt’s work today, but he kept it from being reproduced or exhibited until the end of his life. It is a competent portrait in which the sharp angles of Pound’s features (familiar from Wyndham Lewis’s sketch) are emphasised by the wedge of his moustache, the pointy beard, the cocked hat, the wings of his shirt collar, the V-shaped brows.

In 1930 Brandt moved to Paris, where he was apprenticed to Man Ray. It was a short-lived arrangement. When Ray discovered Brandt had been going through his drawers, examining his prints, he threw him out. Still, three months in Man Ray’s studio was probably enough time to absorb the rudiments of Surrealism. For the next three years, living on an allowance from his father, Brandt travelled, often with Eva, to Spain, Hungary, England, Paris, and briefly back to Vienna, before deciding, in 1934, to move to London for good. He and Eva took a flat in Belsize Park and Brandt, now calling himself Bill, began to establish himself as a British photographer. He didn’t mention his German origins, and, if pushed, denied them.

Despite his eagerness to assimilate, Brandt was culturally a European. In Paris and Vienna he had been exposed to, and had a small part in, the Surrealist and Modernist movements. He was familiar with the photographs of Brassaï and Kertész, both expatriate Hungarians living in Paris, whom he knew slightly (Eva had worked for Kertész in Budapest). He admired Atget’s photographs, which had been appropriated by the Surrealists, who believed them to have the qualities of dreamscapes. He was familiar with Surrealist magazines, such as Minotaure, which had published one of his very early photographs, of a pair of half-clothed dressmaker’s dummies left out on a Paris pavement. A group of his photographs had been included in the 1929 exhibition Film und Foto. He had seen Buñuel’s films and, probably, Pabst’s silent films starring Louise Brooks, Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl. Pabst’s combination of realism and shadowy melodrama, with young women falling from grace into the clutches of sinister and predatory men, are reminiscent of Brandt’s more theatrical photographs.

It was not widely known until studies of Brandt began to be written that many of his photographs were staged. They may have looked like snapshots, but they were carefully conceived mises-en-scène, directed and lit by Brandt, acted out by his family and friends. In his first few years in Britain he set out to photograph a spectrum of national life, mixing set pieces with documentary pictures to produce his first book, The English at Home, published in 1936. It concentrated, not surprisingly, on the country’s most distinctive social feature, class.

Brandt’s uncles, who ran the London branch of the family bank, had town houses and country houses, with butlers and parlourmaids. Most of his famous photographs of the British servant classes were taken in one of his uncle’s houses, and their star, the tall, forbidding servant in her black uniform, starched apron and mob cap, who is seen pulling a bath for her master, or waiting rigidly at table, was his uncle’s housekeeper. Brandt presented them as generic images and turned their subjects into English types (thereby disguising his close relationship to some of them).

Brandt took pictures of social rituals – a day out at Ascot, a garden party at Harrow – and to these he added typical English scenes. His image of a bank holiday on the beach at Brighton has an athletic female figure in the foreground, sporting a sailor hat which reads ‘I’m No Angel’ – this is his sister-in-law, Ester. He photographed poor families in East London, and in the Welsh valleys, which he first visited in 1935. ‘I was probably inspired to take these pictures because the social contrast of the 1930s was visually very exciting for me,’ he wrote in 1959, adding that he ‘never intended them, as has sometimes been suggested, for political propaganda’.

Brandt had read An English Journey, and, after the Jarrow March in November 1936, followed J.B. Priestley to the mining villages of Northumberland and County Durham. On the BBC film he looks fondly at the pictures of the miners and their families. ‘They were so nice,’ he whispers. ‘I had no introductions. I just knocked at the door and asked if I could take photographs. They were very friendly and said: "Yes, do what you like.”’ It is a strange image: the shy, slender figure with the camera and the upper-class, foreign-inflected accent, sliding into the corner of a small cluttered room as the miner, still unwashed from the pit, eats his tea, while his wife looks on (the pose suggests some art-direction on Brandt’s part), or bends over a tin bath in front of the fire while she scrubs him clean. Brandt still sounds amazed as he looks at the picture: ‘They came out of the mines absolutely black.’

When The Road to Wigan Pier was published in 1937, it included a section of photographs whose subject-matter was very close to Brandt’s, but here there was no doubt about their political mission. One showed a family of seven crammed into a small room. Brandt had taken a similar photograph, of a miner’s wife surrounded by her three children, but his picture has a resonance beyond illustration. As Delany points out, the figures of the mother and children ‘have been placed like the composition of a Renaissance devotional painting’. It was their iconic composition (also evident in the social documentary photographs of Sebastião Salgado) that would make Brandt’s pictures last.

His second book, A Night in London, published in 1938, was more personal and more cinematic. It used a series of photographs, almost like a storyboard, to document a ‘typical’ night in London, from dusk to dawn. He mixed documentary pictures with staged nocturnal ‘fictions’, often using Rolf and Ester as models. In ‘Street Scene’, Ester plays a rather primly dressed victim, while Rolf, in a raincoat and trilby, whispers in her ear. ‘Top Floor’, in which a man is seen from the back being embraced by a woman whose hands are entwined elegantly round his neck, is a straight copy of a photograph reproduced in Minotaure, ‘Le Baiser mystérieux’. Brassaï’s Paris after Dark, published in England in 1933, was quickly identified as an influence.

Brandt’s instinct was never that of a reporter. (He used a Rolleiflex, even for his documentary pictures, which requires looking down into the camera to compose the shot, and makes taking pictures a slow, non-confrontational process.) Trained as a studio photographer, he knew how to light a scene or a subject, and how to retouch a picture heavily in the darkroom. Rolf was a theatre director and an actor, able to play the roles Brandt wanted for his pictures and no doubt able to help with a few lighting and staging tips as well. Brandt noticed potential pictures, but he preferred to conduct a controlled re-enactment rather than attempt to capture the event in real time. In this he links two discrete photographic movements more than a hundred years apart. His staging of scenes, coupled with his heavy reworking of prints in the darkroom, allies him to Pictorialism – a Victorian style of making photographs that resembled paintings, which was much derided by Brandt’s time – but it also looks forward to contemporary art photographers, who engage models to re-enact the most ordinary moments of life for the camera, so that they become emotionally charged.

After the war began Brandt received two public commissions that would result in some of his most memorable studies. His pictures of the Underground, taken in 1940, were the result of a commission from the Ministry of Information. The following year, he was asked by the National Buildings Record to photograph historic buildings and monuments threatened by bombing. With his fondness for nocturnes, he remembered the blackout as ‘absolutely fantastically beautiful. No electric light. No cars. Just moonlight. It was so soft, it was like a stage. Stage lighting, very long exposures, sometimes twenty minutes. But there was no traffic . . . no one took any notice.’ In 1943 he went back to Northumberland to photograph Hadrian’s Wall, which was under threat from quarrying. The wall translated easily into a symbol of national defiance and in this commission, as in the other two, he found a visual language which expressed the emotional state of the nation. The pictures of Hadrian’s Wall also marked a shift in his work away from social documentary towards pure landscape photography.

In his preface to Camera in London (1948), Brandt wrote that a photographer must search for the thing that ‘quickens his interest and emotional response’.

I found atmosphere to be the spell that charged the commonplace with beauty. And still I am not sure what atmosphere is . . . Everyone has at some time or other felt the atmosphere of a room. If one comes with a heightened awareness, prepared to lay oneself open to their influence, other places too can exert the same power of association. It may be of association with a person, with simple human emotions, with the past or some building looked at long ago, or even with a scene only imagined and dreamed of. This sense of association can be so sharp that it arouses an emotion almost like nostalgia. And it is this that gives drama or atmosphere to a picture.

In the same essay, he talks about the ways in which printing can enhance a picture’s effect:

The atmosphere of a scene does not need to be attractive or pleasant. On a path over a bare bit of moorland near a mining village I came across a miner leaning over his bicycle; the man’s clothes were black and the grass by the side of the path was black, as it is near pit heads. The scene was dreary in the extreme, yet moving by its very atmosphere of drabness. A dark print of the photograph added to the effect of darkness associated with the miner’s life.

In the 1950s he began to reprint his photographs with a much stronger contrast, building up the blacks until all the mid-tone detail was expunged and they became almost abstract shapes. For Brandt the blacks could never be strong enough (‘Surely London was never that dark,’ a friend said when I was writing this) and also, as he once said, very strong black and white contrast distinguished his pictures more decisively from colour. His compositions, in their most basic elements, could always be reduced to a mass of blacks against a lighter background, and his later style of printing made this even more pronounced. When he made a series of landscapes for the magazine Lilliput in the late 1940s, which formed the basis for his next book, Literary Britain, some of them were reduced, as his later nudes would be, to near-abstract compositions of form and shadow.

Literary Britain was published in 1951 to coincide with the Festival of Britain. Brandt travelled from Hardy’s Wessex to Dr Johnson’s Skye; from Coleridge’s Keswick to George Crabbe’s Aldeburgh; from Blake’s cottage at Felpham to Emily Brontë’s Haworth (David Hockney raised objections when he discovered that for this picture Brandt had spliced together two different negatives to get a convincingly lowering sky). Literary Britain established Brandt as a great British photographer. Just as important, it established him as an artist. In 1984, when the V&A put on a memorial exhibition of Literary Britain to mark Brandt’s death the previous year, Mark Haworth-Booth wrote that ‘Brandt’s landscape photographs are as indelibly part of their period as the operas of Britten and the . . . works of Piper. They are part of the dream of the decade.’

Brandt had been photographing nudes intermittently since the early 1940s, and of all his pictures, these are the ones that have been the occasion for the most anxious examination of his psyche. Yet for all their surrealistic, dreamlike, Alice in Wonderland qualities, they are very solidly photographs of naked women sitting in rooms. If anything, it’s the rooms that convey the mystery and the hint of sexual menace. Brandt called them ‘experimental interiors’, and admitted that one of his early experiments, usually called the ‘Hampstead nude’, was ‘a bit inspired by Balthus, whom I then very much admired’. There is certainly a similarity: a pale-skinned, naked young girl sitting on a wooden chair in a slightly shabby floral Victorian bedroom, watchfully doing the photographer’s bidding. The room seems too small for her, as if the walls are closing in.

Brandt had a clear idea of how he wanted his nude photographs to look. Instead of studio nudes, he wanted to photograph naked women ‘in real rooms’, which removed them from the protection of the fine art tradition and brought them closer to genteel pornography. He was also influenced by Gregg Toland’s cinematography for Citizen Kane, which came out in 1941 and which, according to Delany, Brandt watched many times. Toland used a wide-angle lens and unnaturally deep focus. Brandt wanted a camera that could give him the same effect, so that when he photographed rooms, he could, as he said, ‘get the ceilings in’. He found one in Covent Garden for five pounds. It was an old wooden Kodak of the kind the police used for scene-of-the-crime photographs and it had a very wide-angle lens. This camera, Brandt said, could see ‘like a mouse, or a fish, or a fly’. Subjects in the foreground and in the distance were sharp, but anything close to the lens became severely distorted.

Rather than try to compensate for the distortion, Brandt worked with it. He moved the camera in closer so that the body burst out of the frame. Instead of masses of black form, he had masses of white; the flesh and the limbs became almost abstract. From the 1950s to the 1970s Brandt used the human body like a sculptural material, moulding it, bending it, cropping and foreshortening it, so that his pictures were an exercise in form: knees, a belly button, a torso from the back balanced like a huge pebble on the beach. These nudes, taken on the beach in East Sussex and in the South of France, are reminiscent of Henry Moore’s sculptures, or Edward Weston’s New Mexico nudes.

At roughly the same time that he began the nudes, Brandt also began to take formal portraits, which he would continue to do until the end of his life. They were usually commissions for magazines, and he restricted the subjects to artists or writers. Unlike Cecil Beaton’s portraits, in which Beaton focused his decorative powers on the sitter to make a flattering and glamorous image, Brandt made little accommodation for the shift in genre. ‘I always take portraits in my sitters’ own surroundings,’ he explained. ‘I concentrate very much on the picture as a whole and leave the sitter rather to himself. I hardly talk and barely look at him.’ The portraits share many of the characteristics of his nudes and landscapes. A series from the early 1960s uses the same wide-angle distortion, with the subject looming large in the foreground. Brandt wasn’t hoping to catch his subject unawares, as Cartier-Bresson might have done. Rather the opposite: he thought of a picture, with the subject usually in their own room, or in a landscape associated with them, and went to great lengths to get it. (It took him ten visits before he could persuade Picasso not to smile.) But what most of his portraits have in common is the impetus to ‘make the familiar strange’.

Brandt’s final pictures were a series of questionable nudes, in which Delany finds proof of repressed sado-masochistic urges. He admits that many of Brandt’s friends would have preferred them never to have been published, ‘yet to a biographer,’ he claims, ‘they open a window into Brandt’s lifelong obsessions with suffering and constraint.’ ‘Motorcycle Girl’ shows a female figure (apparently she was a courier who regularly modelled for Brandt’s £10 fee), sitting at a table naked but for a pair of rubber gloves. ‘Bound Nude’ is a figure whose arms are loosely bound to her naked torso with dark string; the face has been blacked out with ink. There seems something weary and half-hearted about these photographs, but to Delany they signify ‘hostility towards women . . . combined with using women to convey Brandt’s own feelings of victimisation’. Having found a Surrealist pedigree for them, his verdict is still inconclusive: ‘As with all the Surrealists, it is impossible to say whether Brandt was deliberately exploiting images from the subconscious, or just releasing them.’

Delany’s persistent attempts to find the ‘deeper layers of private significance’ in Brandt’s pictures often lead him down a cul-de-sac. But one of his more curious hypotheses comes from his discovery of a subtext to the Hampstead nude, which Brandt called, privately, ‘The Policeman’s Daughter’. The title had already been co-opted as evidence of Brandt’s fascination with the figure of the policeman, or, more simply, it was said to be a reference to the police camera. Delany suggests that the title refers to an unpublished novel by Swinburne, ‘La Fille du Policeman’, which is ‘set in London’ and is

a feeble burlesque of Sade and other French Revolutionary writers . . . not a work to be taken seriously in any way, except as evidence for Swinburne’s well-known interest in sado-masochism. That could have been the interest for Brandt, too. He had long been fascinated by the authority figure of the policeman; in the Swinburne novel it is a policeman who is unable to protect his daughter, or revenge her death.

Delany draws the conclusion that ‘somewhere in this hall of mirrors was a sexual fantasy that Brandt was satisfying by calling his nude "The Policeman’s Daughter".’ Bert Hardy, a Picture Post photographer,

told David Mellor that Brandt hired prostitutes to pose for some of the nudes of this period, and that they also ‘took care of him’. If so, Brandt was probably still trying to cope with some scene of shame or humiliation from his childhood, or from the torments inflicted on him at school. Being mistreated by a woman in adult life can be a compensation for childhood pain.

Poor Brandt. Everything in this book suggests he would have hated the idea of a biography that not only interrogated his past but also extrapolated theories from his photographs. He would probably have said merely that he was a photographer, primarily interested in shadow and form and light and what the camera could do; he liked manipulating prints in the darkroom; he took pleasure in prints that sold well; he had an instinctive vision of photography that allowed him to move naturally through the genres; the nudes were his favourite pictures. This story would not substantially undermine the pleasure of looking at his pictures, and it would enable the viewer to do so with a clearer head. His famous reticence might have protected him in life, but did not serve him so well after his death.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.