Thanks to Michel Foucault and Discipline and Punish, history students now graduate knowing more about the history of the body than about the English Civil War or the Industrial Revolution. At the same time, everyone has their own idea about what body history should be about. It was Foucault’s view that power always expresses itself by way of the body: his history was (at least in its inception) a corporal politics, intended to reconfigure our understanding of power. At Berkeley he ran a seminar from which two other major books emerged: Peter Brown’s The Body and Society: Men, Women and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (1988), which explored the theme of carnality and spirituality, and Thomas Laqueur’s Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud (1990), which offered a radically new approach to the history of medicine. Now there are bodily histories of the emotions, of sexuality and gender, of political philosophy (‘the body politic’), of colonialism, of warfare: indeed, anything that has a history now has, or will surely shortly acquire, a bodily history.

The real excitement of body history occurs when (as on first reading Foucault) things that would appear to be too straightforward to have any history at all turn out to be historically peculiar and specific. The body, something all human beings of every age would appear to have in common, is, we now realise, ‘constructed’, ‘a product of culture’. Take nakedness. One may doubt whether early modern English men and women were ever naked. In the mid-17th century Quakers went ‘naked for a sign’, but they often turn out to have been wearing sackcloth coats – ‘naked’ here means without shoes, hats or outer garments. Men and women both wore smocks, and you could be ‘naked in your smock’. (There was no ‘underwear’, so everyone was naked under their smocks.) People did not take their clothes off to go to bed, but they did take off their hats (if they were men) and coifs (if they were women); thus a brother and sister were suspected of incest when they were discovered in bed together, ‘both bareheaded’. John Donne was exploring a metaphysical extreme of sensuality when he wrote a poem in praise of ‘full nakedness’: a poem which describes his lover’s clothes, but not her body, and in which his hands rove in unexplored places, like those not of a husband, but of a midwife. Whether Donne himself ever saw and touched a fully (or stark) naked body, the point of the poem is surely that his readers will scarcely be able to imagine anything so strange. Renaissance artists had rediscovered the classical nude two centuries before, but Donne was (I suspect) the first Englishman to propose going naked to bed.

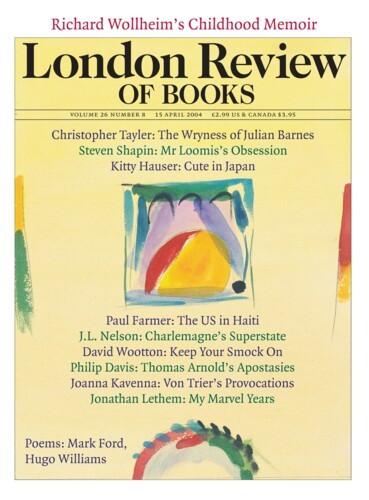

One reason people kept their clothes on is that they were almost never alone. In 1674 Elizabeth Myres, like many servants, slept in a truckle-bed at the foot of her mistress’s bed. When her mistress took a lover it was Elizabeth’s job to help him pull off his shoes, after which he would climb into her mistress’s bed and pull the curtains close; Elizabeth would lie a few feet away hearing ‘kind words and expressions of love pass between them’. Nobody expected her to leave the room. And because 17th-century people kept their clothes on, the boundary between flesh and cloth was indeterminate. According to the Book of Job, in the King James version, we are clothed in skin and flesh; but one might equally describe early modern men and women as fleshed in clothes. ‘To be laid out upon a petticoat’ meant to have sex. When Queen Elizabeth imagined the ultimate destitution she said she might be cast out of her kingdom in her smock – she could imagine being deprived of everything, but not of her smock. Maria, in John Fletcher’s The Woman’s Prize, goes further: she imagines being reduced to half a smock, but not to no smock at all. To be in the world, since the Fall, was to be clothed.

Since flesh and cloth were inseparable, narratives of sex were nearly always stories about clothes not bodies, and the distinction between voluntary and forced sex depended on how and by whom a woman’s smock was lifted. A woman who ‘took up her smock very willingly’ had obviously consented to sex. Margaret Browne testified to seeing her neighbours having sex: ‘He plucked up her clothes to her thighs, she plucked them up higher.’ This said everything – though, in order to prove that she was really there, Margaret added that her neighbour’s hose was of ‘a seawater green colour’. But a woman who said that a man ‘took up her clothes in a very uncivil way’ was describing forced sex. Another was tripped up by a young man who threw her on the ground, ‘taking up her clothes, leaving her naked, and attempting to have his pleasure with her’.

Such narratives were not then, as they would be now, stories of rape. The crime of rape was slowly undergoing a process of redefinition, from abduction (as in ‘the rape of the Sabine women’) to sexual intercourse without consent, but rape was hard to prove and juries were reluctant to convict. Pepys describes young women in London being abducted in broad daylight by gentlemen who had no reason to fear the authorities. Women told stories of forced sex not to bring prosecutions for rape, but in order to explain away illegitimate births (which were punished by a flogging). In the absence of a pregnancy there was little point in reporting a rape. One woman described being assaulted three times by Thomas Hellyer. On three successive Sundays he had forced her onto a bed, pulled up her clothes, and sought to have carnal knowledge of her for between half an hour and an hour. She denied that he had succeeded for all their prolonged and repeated wrestling: the purpose of her testimony was to corroborate the claims of another servant whom he had made pregnant. In this context, denying he had succeeded preserved her own honour, while insisting he had lifted her clothes proved him to be capable of fornication.

In her fine book, Laura Gowing emphasises the extent to which women were vulnerable to sexual assault by their employers. Servants lived in their master’s household, and most people passed through an extended period of service before marriage. Nevertheless, the vast majority of servants seem to have escaped impregnation – illegitimacy rates were low, between 2 and 5 per cent. Safety lay in numbers; even a woman alone with a man could normally expect to have her cries heard. Katherine Osborne, examined for illegitimate pregnancy in 1664, gave in to the demands of William Adams when he promised to look after her if she became pregnant:

Being demanded why she did not cry out whilst [he] did attempt that fact, his wife being at that time dressing of her child by the fireside in the kitchen and near unto the place, saith the reason was for that [he] said that if she did cry out he would stop her mouth, upon the saying of which words (which were whisperingly spoken) [she] was silent.

Was her silence a form of consent? Quite different was the situation of Elizabeth Thorne, who met a stranger in a field by chance. He drew his sword on her and threatened to kill her if she didn’t yield; she resisted, and was still traumatised by the experience years later. There had been no one nearby to hear her cries.

A single woman who became pregnant lost any right to what we call privacy (which implies having access to a private space) and they called modesty (which implies having no occasion to feel shame in the presence of others). If she was suspected of concealing her pregnancy, other women had the right to search her body to confirm it. She was required to give birth in the company of other women, for the law assumed that a woman who gave birth alone and then claimed her child was stillborn had done away with it. The midwife was required to withhold assistance at the birth until she had named the father of the child, for otherwise the cost of supporting mother and child was likely to fall on the parish; this gave rise to a strange form of the verb ‘to father’ where a woman fathered a child on a man by declaring him to be its father. At the Bridewell in London, single women suspected of being whores were inspected by other women to establish if they were virgins. These are examples of what Gowing calls ‘the politics of touch’. In all of this women were held responsible for what had been done to them by men – in Holland, Pierre Bayle attacked this hypocrisy, and followed his own logic through to the point of defending abortion and infanticide. No 17th-century English man or woman seems to have had a comparable grasp of gender politics, and at every point the enforcement of a double standard required female co-operation. The witnesses against women charged with fornication or infanticide are nearly always women.

Gowing’s aim is to provide a ‘social history’ of the female body, concentrating on intercourse, pregnancy, childbirth and breast-feeding. Where earlier historians have treated the lying-in period after childbirth as a happy time when women were, for a change, in charge, their every whim catered to during a month of licensed feasting and gossiping, Gowing takes a ‘less optimistic view’, finding angry wives turning up when their husbands’ mistresses are lying-in and threatening to kill them. The central difficulty with the book is that, like Gowing’s earlier Domestic Dangers (1996), it is based almost entirely on court records. Inevitably, few of her stories have a happy ending. But this is hardly surprising: imagine writing a history of Christmas on the basis of the records of a hospital accident and emergency department. Gowing has more to say about rape than about love-making, more about illegitimate births than legitimate ones, more about conflict than co-operation.

We learn from her that it was primarily by touch that women diagnosed pregnancy, both in themselves (the experience of ‘quickening’) and in others. But many types of touch escape her attention. A touch could signify love (‘the inly touch of love’ of Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona echoes the outward touch of the lover), or lust (there are paddling palms in both Hamlet and The Winter’s Tale), or parental affection (‘the nearly touching touch the father feels towards his son most dear’ in the Countess of Pembroke’s translation of the Psalms). It could signify a promise or a threat or a reproof. One could be touched with madness, or with remorse, or with disgrace. Before the word ‘sympathy’ meant fellow-feeling, before there was a word ‘fellow-feeling’, people were ‘touched’ by the sufferings of others. People ‘handled’ animals, ships, matters of business, themselves and other people. Children and servants were frequently beaten, and judicial punishments were for the most part corporal. Far more than ours, this was a tactile society, and self-consciously so in that it was increasingly suspicious of spiritual and immaterial entities. The words ‘embodied’ and ‘corporeal’ were newly invented to identify those qualities that can be experienced by touch – by the end of the century these were the ‘primary’ qualities with which science was properly concerned. The new science, placing itself in the tradition of doubting Thomas, was a hands-on affair. There was a sensuality, an epistemology, a morality, even an aesthetics of touch. And yet, of all the five senses, the history of touch is the hardest to write. The history of the deaf and the blind can tell us a great deal about the role of sound and sight in particular societies. (The classic text is Diderot’s Lettre sur les aveugles.) The history of touch has no comparable external reference point. Of the five senses, this is the only one that is indispensable and universal.

Gowing has successfully brought together two traditions, that of Laqueur, concerned with different ways of imagining the body, and that of Foucault, concerned with different ways of disciplining it, to give us a new history of women in 17th-century England. My objection to the book is that it implies that the Foucauldian dyad of knowledge/power covers the whole range of human experience; one day historians may find this notion of embodiment (which has so little to say about either sensuality or sinfulness) every bit as puzzling as we find the beliefs of 17th-century midwives. Other starting points would have given Gowing very different types of embodiment. Take Fletcher’s The Woman’s Prize. It was written as a reply to The Taming of the Shrew, and in it women – tomboys, we are told, who threaten to make themselves cocks and piss on walls – revolt against male dominance, arm themselves and set out to tame the men. It is inevitably a play about touch: about blows, ‘handfasts’ (or handshakes) and sexual fumbles. From the point of view of the female characters, it is the male touch which spoils everything: women are ‘too divine to handle’. And it is inevitably a play about sex, but since it is performed under the censor’s watchful eye, it becomes a play about kissing. There are bets on how many kisses will be exchanged, and the names for kisses multiply through the play: ‘busses’, ‘dry kisses’, ‘licks’. And with the kisses come tongues. Maria, the anti-Kate, has ‘many tongues’, ‘strange tongues’; in the space of a few lines her tongue is ‘lying’, ‘lisping’, ‘long’, ‘lawless’, ‘loud’, ‘lick’rish’ (or lecherous). Women make up for not being men with their tongues.

The world of The Woman’s Prize overlaps with the world described by Gowing: Maria assumes that if she refuses to have sex with her husband he may lay claim to the bodies of the dairymaids. But Fletcher ends the play with neither side able to declare victory. The epilogue announces that its purpose has been ‘To teach both sexes due equality/ And, as they stand bound, to love mutually’. Gowing would have produced a very different history of women’s bodies if she had turned from her court cases to poetry and plays; but anyone who wants to understand women as they are embodied in plays and poems will need to read her book, for in it we encounter what Stephen Greenblatt has called ‘the touch of the real’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.