I gave the little girl a name. Rita. I doubt it’s a common name in Iraq but it seemed to fit her round face, brown eyes and straggle of blood-soaked hair. The military medics staunched the bleeding from her bullet wounds and whisked her off to a field hospital by helicopter, leaving her mother’s corpse to be turned over to a local mosque for burial. I saw most of what happened to her family, her father, mother and baby sister, near the checkpoint on Highway 7, south of Kut, beside the deep irrigation ditches and fields of green wheat. But in the hectic aftermath of the clash between US forces and the Iraqi soldiers who had appeared to open fire on the family I understood less the more I was told. Why were they travelling down the road towards the barrels of US tanks, and why did Iraqi soldiers chase them in a truck, dismount and shoot them? Rita’s father was a civil servant called Haytham Rahi, the Kuwaiti translator, sweating in his US fatigues, discovered. But what combination of decisions, beliefs, mistakes and misfortune led him to catastrophe was a mystery. It took six weeks for other journalists to track down the family, unravel their tale of bad fortune and learn that Rita’s real name was Tghreed.

I don’t like leaving stories unfinished, but I got used to it. The day after Rita was shot, when any reporter with a car and a translator would have tracked her down, I had to get back into my US armoured vehicle and trundle onwards with the Marines to the next town to be subdued. The mind-numbing physical discomfort of military life resumed. Soon I was at the next stop on the map, trying to impose coherence on what had happened that day, surrounded by troops puzzled at their orders, acting on flimsy local intelligence and fearful of attacks from behind every palm tree. Rita was yesterday’s news.

Accompanying the US military on an invasion inevitably involved compromises. We had few translators, and little say in where we went; we could not branch off, nor could we linger when our hosts moved on. We moved so fast there was little time to write during the day: we had to phone snippets to editing desks back home, and they stitched the work of many into a story. We spent as much time protecting equipment from the elements and military clumsiness as we did gathering information. At night, when lights were forbidden, we sat in the dirt under blankets to write – until our computer batteries expired, sandstorms wore us out or the call to arms forced us to pack up and move on at some wretched hour. If you were a seasoned war reporter toting your battle-scarred laptop and were unlucky enough to be ‘embedded’ with a battalion in charge of water supplies, there was little you could do about your distance from the front line. If your unit commander took away your satellite phone because he was afraid you might inadvertently tip off the Iraqis about the war plan, you could do nothing but fume incommunicado. And, most important, being positioned inside the military cordon meant frustratingly brief contact with Iraqi civilians.

The Pentagon made little secret of its self-serving motives for inviting us to take part in the biggest deployment of journalists alongside soldiers since World War Two. There was no reason for the generals to expect journalists to glorify the war (although some officers did seem to envisage puff-pieces about the bravery of their infantrymen), but having hundreds of reporters with front-line troops allowed the military to say they were being as open as security allowed. At the same time, by depriving the embedded journalists of key tactical details, which were available only further up the command chain, and carpet-bombing correspondents at Central Command in Qatar with selective information, the US and British military held at bay the kind of intelligent questioning that might have provoked popular disquiet and political second-guessing. Round-the-clock television made possible by lightweight satellite phones and other technological advances allowed a version of the war to be instantly available at home, but the speed of transmission trimmed both accuracy and depth. A series of hasty impressions was often the most one could hope for in the pell-mell military advance: critics have implied that correspondents were compromised by being so close to the action.

But seeing the attack on Rita’s family allowed me to write about the civilian casualties of a conflict that was supposed to spare such people. Better that than sitting in a briefing room being lied to about the incident by one side or the other, or interviewing Mr Rahi in hospital and trying to piece together what happened without having been there. Travelling with the Marines meant I could not pursue Rita’s story, but the follow-up is what you write when armies bar you from the battlefield. I wrote my share of these stories in Bosnia and knew they gave a very approximate version of what had occurred. There were no reporters embedded with General Mladic’s troops when they captured Srebrenica and shot the town’s male inhabitants. Across central Bosnia in 1993 armies tried to leave no witnesses alive to talk to reporters, who could only stumble along in the wake of conflict. The risks of embedding pale in comparison to such deceit.

Before we set out I was surprised to hear the opinion expressed that an unwillingness to offend would prevent journalists reporting the shortcomings of the troops we accompanied. We were to be hostage to military kindness, stultified by Stockholm syndrome. And I shuddered when a Marine Corps general promised we would be adopted by his men and strike up lifelong friendships. Uniformed men and reporters were brought together by common danger: no special precautions were taken to ensure my safety, and the shared discomfort of living in foxholes meant we moaned about the same miseries. But corruption would take a bit more than the loan of a sleeping bag or the offer of a cup of coffee on a frigid desert morning. Difference of outlook and experience kept reporters and soldiers apart. At nearly forty I was more than twice the age of many of the Marine infantrymen in the battalion I accompanied. Few of the officers were older than me or had more combat experience. Our attitudes to hierarchy, authority and government were diametrically opposed. I was not there to argue the merits of the conflict, but it was easy to feel distanced from military companions who regarded the assault on Iraq as a straightforward war of liberation and saw themselves as descendants of the men who landed on the Normandy beaches.

Picking holes in press coverage seems to have stood in for opposition to the war once it was clear that conflict was unstoppable. Correspondents did, of course, get things wrong, particularly in their eagerness to report military progress, but we were both misinformed and disinformed. I was particularly chagrined to hear Qatar spinmeisters insisting there were no problems with supply lines when my unit’s rations had been cut to a third, barely enough to live on. After trucks fought their way through hostile towns to resupply us, I found myself hoarding rations like a shipwreck survivor. And US generals appeared to lie to their own men, knowing that what they said would get to journalists, be reported and heard in Baghdad. The quality of information varied day by day. Two usually reliable middle-ranking officers tried to persuade me that the killing of a large number of military-age but unarmed Iraqi men aboard buses that had been blasted off the road might well have been the work of Saddam’s fedayeen fighters. It was an explanation that would have required staggering naivety to accept and it was contradicted by other officers of both higher and lower standing, who suggested that trigger-happy US units had not given the Iraqis a chance to surrender.

The US military also got things wrong for more innocent reasons. It is notoriously difficult to communicate anything complex by radio, and information was often mangled in transmission. And the further down the ranks, the looser the attachment to reliable facts. Events were refracted through a prism of prejudice or wishful thinking as word passed from soldier to soldier. The average infantry grunt is prone to rumour-mongering, if only out of a desire to relieve the monotony of his duties with some colourful tales. He exists in an information vacuum, without a radio or other contact with the outside world, and in Iraq knew less than anyone else what was happening. I spent a lot of time refuting claims that Saddam’s body had already been found.

Many US field officers were candid to the point of indiscretion. They, too, were struggling to overcome ignorance, and appeared poorly briefed about Iraqi society and culture. I saw a US captain directing heavy fire onto a minaret in the centre of an Iraqi town in the belief that it was an observation tower. Many of the civilian deaths at US checkpoints were caused by poor training in handling civilians and by mundane mistakes, such as not having any signs in Arabic to warn vehicles to slow down. I saw a pair of old farmers blasted by US guns because they failed to spot a flimsy line of barbed wire on the road, drove through it and were assumed to be suicide bombers. The shortage of interpreters compounded the general notion that all Iraqis must be able to understand commands shouted in English.

No one reported the Iraqi soldiers’ perspective, of course: the Baath regime proscribed it and it would probably have been suicidal. So none of us recorded the terror of Iraqi tank commanders certain they would be cooked inside their crew compartments by American TOW missiles, or witnessed the apprehension of the Republican Guards as the condensation trails of B52 bombers appeared overhead. But journalists were in enough places to ensure that the coverage of this war was not sanitised, or reduced to a paean to military prowess, as was much of the reporting of the 1991 Gulf conflict. Like all wars, this one was unhygienic and deadly, and it showed. Pictures of corpses filled the newspapers, wounded civilians were shown on the evening news.

Already the grim images of the war have become jumbled in my mind. When I think of the dismembered dead strewn around a smouldering bus I also hear the angry thudding of the helicopter gunships which days earlier had fired rockets over my head with a sound like fabric ripping. When I think of Andy, the CIA operative, it is not his face that I remember but his sepia Stars and Stripes cap badge. Andy, who wore US college student casuals and an M4 carbine across his chest, was not pleased to be spotted. He offered to give me the inside track on the day’s mission in exchange for not mentioning he’d been there. I think of Iraqis, celebrating Saddam’s downfall, throwing flowers at American tank crews, while the soldiers, who had expected more of a fight, looked bewildered as they cleaned the petals from their armour. After three weeks of war they still had the bug-eyed look of fear beneath their bravado. All these images have become one memory, a tough one to shake.

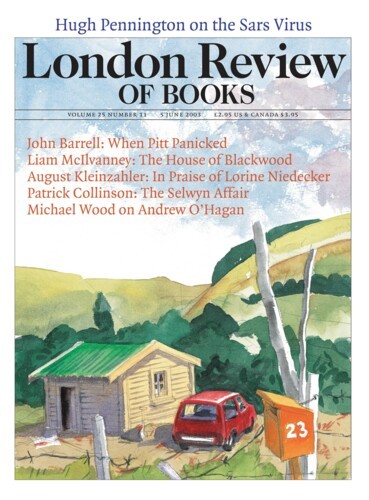

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.