The Edwardians turned out for some curious entertainments. In 1907 they flocked to hear Clara Butt, that towering contralto, sing the newly published Cautionary Tales of Hilaire Belloc, Liberal MP for South Salford and defender of the Catholic faith. All seats were sold countrywide. The Cautionary Tales – which tell of Henry King, ‘Who chewed bits of String and was early cut off in Dreadful Agonies’, and Rebecca, ‘Who slammed Doors for Fun and Perished Miserably’ – are in iambic octosyllabic couplets and can run to fifty lines or so. How did Clara Butt contrive to sing these metricated fables? What tune, or tunes, did she employ? Were children, at whom these tales were supposedly directed, admitted under parental guidance? And what did Belloc think of her efforts, which are said to have done nothing but good to his sales? (‘I’m tired of Love: I’m still more tired of Rhyme/But Money gives me pleasure all the time.’) As Joseph Pearce tells in Old Thunder, he was already fretting over his increasingly lightweight reputation for comic verse and was pursuing ‘meatier material’. He had under his belt The Modern Traveller, that splendid satire on African exploration (‘Whatever happens, we have got/The Maxim Gun, and they have not’), and The Path to Rome, an idiosyncratic bestselling account of his solo pilgrimage by foot across Europe in 1901, lodging at one franc a night and fording rivers as necessary.

In that year of the Butt performances he told a friend ‘I have written one good poem every day now for 4 months’ – not bad going for a busy MP. Usually he insisted that he wrote verse, not poetry. His output ranged from those cautionary echoes of Struwwelpeter to roistering drinking songs, from tender lyrics to excoriatory ballades, from moral alphabets to ‘imitations and grotesques’ (among which must be counted his ‘Newdigate Poem’ in praise of ‘The Benefits of the Electric Light’: ‘A smell of burning fills the startled air –/The Electrician is no longer there’). In later years he told Maurice Baring: ‘Verse is the only form of activity outside religion which I feel to be of real importance; certainly it is the only form of literary activity worth considering.’ That he should now be remembered and quoted for his frivolities is the penalty of his genius. Where would the leader-writers, financial pundits and even cartoonists be without his renowned two-liners like ‘And always keep a-hold of Nurse/For fear of finding something worse’? Belloc had the same gift that he attributed to another genius, limpidly defined as that of ‘the choosing of the right words and the putting of them in the right order, which Mr Wodehouse does better, in the English language, than anyone else alive’. Belloc added to exactitude and an airy fluency a brisk heartlessness:

We had intended you to be

The next Prime Minister but three:

The stocks were sold; the Press was squared;

The Middle Class was quite prepared.

But as it is . . . My language fails!

Go out and govern New South Wales!

He was the outstanding practitioner in a golden, occasionally leaden, age of light verse (Chesterton, Beerbohm, Wodehouse, Harry Graham, Baring, Squire, Seaman, ‘Evoe’ and, improbably, Housman, along with many others, not forgetting the prolific Anon). Even the newspapers published well-turned light verse daily and the postal schools of journalism began to teach the tricks of the trade (never leave a line unrhymed, or be rejected for slovenliness). Thanks to the rage for what the affected called vers de société, and the forced memorising by schools of the Lays of Macaulay and other rumbustious numbers, there were probably fewer people with tin ears and no sense of scansion than at any other time. It was even possible to make a living by cultivating the once despised Comic Muse (a short generation later I kept myself in cars and steamship tickets with copious biodegradable light verse).

For some reason, Belloc’s verse is meagrely quoted in this latest biography. Not all libraries have yet consigned to the skip two excellent earlier Lives, A.N. Wilson’s Hilaire Belloc (1984) and Robert Speaight’s The Life of Hilaire Belloc (1957). If a debunker were needed for this wittily bellicose (‘Bellocose’, Wilson suggests) Catholic author of more than 150 publications (which smacks of thraldom to the work ethic some call the Protestant vice), the calm and fair-minded Joseph Pearce is not the man. He is concerned to exculpate Belloc from the grosser charges of Jew-baiting and to argue that the books written by this hammer of the heresiarchs to undermine the Whig view of history are not as contemptible as spluttering academics have maintained. To summarise Old Thunder’s career: the son of a French father and an English mother, he was born in 1870 near Paris in a house which only weeks later was sacked by the Prussians. At 12 he was in love with Homer. Already he was disturbed by the Victorian drift to doubt. Aged 21, still a Frenchman, he served a year in the French artillery. At Oxford he became president of the Union and was hailed ‘the Balliol Demosthenes’. All Souls’ refusal to grant him a fellowship – did the examiners shy at that statuette of the Blessed Virgin on his desk? – left him with a grievance for life. In 1896 he married the American Elodie Hogan in California, after some earlier heavy foot-slogging on that continent.

The turn of the century saw the birth of his literary partnership with G.K. Chesterton, who was attracted by ‘the scent of danger’; in return Belloc championed him, in a famous poem, against abominable dons. Shaw teased the pair as ‘the ChesterBelloc’, two halves of a pantomime elephant. Stirred by political ambition, Belloc contested South Salford, where he was taunted as Papist and foreigner, and later as booze advocate. Waving a rosary on the hustings, and explaining what he did with it, he told his audience, ‘If you reject me on account of my religion, I shall thank God he has spared me the indignity of being your representative’ (silence, then thunderous applause). In his maiden speech he condemned the exploitation of Chinese labour in South Africa. His fellow Liberals were as unamused as the Edwardian plutocracy when he bore down on two scandals which have a present-day ring to them: the secrecy under which political funds were garnered and administered and the award of peerages to generous donors to party funds. Belloc’s own secular creed was distributism, sometimes called agrarianism, more of a philosophy than a practicality. Disgusted with Parliament, he decided he could do more good by his pen. In 1913 his wife died, leaving him with five children. World War One found the ex-poilu and author of five books on famous battles a well-paid and respected military commentator in Land and Water, until his excessive optimism earned derision (a spoof entitled What I Know about the War by Blare Hilloc consisted of blank pages). In the 1920s he fought a six-year feud, and expended 100,000 words, in an attempt to deflate H.G. Wells’s Outline of History, which brushed aside Christianity and held that scientific progress was all. Next came a vicious dispute over the falsification of history with Professor G.G. Coulton, of whom it was remarked that ‘the law of correspondence with Dr Coulton is the survival of the rudest.’ Belloc welcomed Mussolini, as he later welcomed Franco. In World War Two he was again a military commentator, although a short-lived one. He became one of a singularly stricken company who lost a son in uniform in both wars. In 1943 he declined Churchill’s offer to propose him for a Companionship of Honour, not caring for some of the names already on the roll. The postwar years saw a premature slide into dotage, unsparingly described by Malcolm Muggeridge and Evelyn Waugh (‘Smell like fox’). He died in his Sussex home in 1953.

Belloc was sometimes taxed with being the author of W.N. Ewer’s much anthologised squib: ‘How odd/Of God/To choose/The Jews.’ As a young man he had maintained Dreyfus guilty against all the evidence to the contrary. Was he an anti-semite? In his own definition, and in his own italics, an anti-semite was someone who wanted to get rid of the Jews, who hated Jews as Jews. ‘English fiction has made fools and scoundrels of the Jews,’ Pearce quotes Frederic Raphael as saying, ‘but it has rarely attributed the ills of the world to their very existence. It needed Hilaire Belloc and Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, none of them native Britons, to introduce to English literature the programmatic hatred that mere distaste was too lazy to confect.’ Pearce, who doesn’t agree with Raphael’s characterisation of Belloc, shows to what anxious lengths Belloc went to dissuade his friend (and occasional ghostwriter) Cecil Chesterton from Jew-baiting in the New Witness during the Marconi affair. By way of evoking the sentiment of the day he quotes some hair-raising rants published in the Times about the Jewish murderers, butchers and fiends who helped to organise the Russian Revolution. But then Pearce doesn’t mention Belloc’s poem mocking Jewish financiers in the Boer War, and celebrating ‘The little mound where Eckstein stood/And gallant Albu fell/And Oppenheim, half-blind with blood/Went fording through the raging flood’ and so on.

Belloc devoted furious energy to correcting the ‘warped’ version of English history taught in schools and universities, thanks to the likes of Gibbon, Macaulay and ‘the modern writer Trevelyan’. He groaned to think of ‘the weary work of fighting this enormous mountain of ignorant wickedness that constituted “tom-fool Protestant history”’. Macaulay was ‘a bold and resolute liar’ ever ready to suppress, distort and mis-state; inevitably a readiness to do just that was alleged against Belloc. Shaw’s view was more lenient: ‘Mr Belloc urges the view of history that the Vatican would urge if the Vatican were as enlightened and as free as Mr Belloc.’ At the very least, Pearce says, by the vigour of his Catholic brief Belloc has enabled conscientious students of history to see both sides. He is delighted to find Norman Stone, at the time a professor of modern history at Oxford, writing in the Sunday Times that he considers Belloc a more perceptive historian than G.M. Trevelyan: ‘I think that, in the end, I shall go to Trevelyan’s enemies, Hilaire Belloc or Lord Acton, both Catholics, for an understanding of modern England.’

Belloc wrote no autobiography: he felt it was not really a gentlemanly thing to do; autobiographers usually offered too little or far too much. His now hackneyed and rather inferior quip – ‘When I am dead, I hope it may be said:/”His sins were scarlet but his books were read”’ – prompts the thought that if he had committed any scarlet sins they would have been made public long ago. His elderly infatuation with Lady Juliet Duff, subject of many epigrams, was probably no more than that, and Pearce has nothing to say about it, unlike Wilson. The death of his wife, after which he wore black for life, was a dividing mark in his career. There were fewer of those half-legendary carousals where tireless practical jokers downed ‘the Blood of Kings at only half-a-crown a bottle’ and bellowed songs about Burgundy and Roncesvalles. Some of that gusto now animated the younger generation. At King’s Land in Sussex the widower’s children, we now learn, ran dangerously wild. There were ‘death-defying’ pranks which ranged from jumping onto moving trains (and not paying) to climbing the sails of the adjacent windmill or dashing between them when they were revolving. Master Hilary, who kept homemade gunpowder in his trouser pocket and strewed it round the dinner table in order to blow up the plates, would have been an ideal subject for a new cautionary tale.

The parental urge to write purely comic verse was now under firm control, however. Clara Butt, ‘damed’ for singing patriotic wartime songs, might have found more singable Belloc’s much fêted ‘Tarantella’ (‘Do you remember an inn, Miranda?’), a highlight of 1920. The pressures of bread-winning grew ever more onerous. Belloc always seemed to be writing several books at once, and chasing multiple deadlines. An ‘Epitaph upon Himself’ ran: ‘Lauda tu Ilarion audacem et splendidum,/Who was always beginning things and never ended ‘em.’ Many editors, however, were wary of commissioning articles. His own reputation as an editor was a poor one, even when he took over G.K.’s Weekly after Chesterton’s death. As a literary editor on the Morning Post he had been a wayward absentee. It was left to (Sir) Alan Herbert, with whom he went sailing, to show that a brilliant and prolific writer of light verse could also be an effective MP and get his own Act on the statute book. In the mid-1930s the roll-call of Belloc’s lecture stops reads like a muddled gazetteer: Nassau, Nazareth, Marseille, Philadelphia, Beirut, Vicenza, Lucerne, Vigo, Pau, Tripoli, Aleppo . . . How many English men of letters stopped off at Aleppo? Already he had suffered two minor strokes. It is painful to read of the decline in his ebullience and stamina. The man who had written the lives of Danton, Robespierre, Marie Antoinette, Napoleon, Joan of Arc, Richelieu, Wolsey, Cranmer, Cromwell, Charles I and James II was now to be found lamenting ‘this horrible book on Louis XIV’, which he had never wanted to write, and mislaying the uncompleted manuscript of his life of Elizabeth Tudor.

Throughout, his battle-cry was, as this book reminds us, that of Pius IX, Pro Ecclesia Contra Mundum. He had always liked to pop in on the Pope of the day; Beerbohm has a sketch of him giving the Pontiff the date of England’s forthcoming conversion. The ‘boozy halo’ (H.G. Wells) he cast over his Catholic faith, and the bombast and jocosity with which he defended it, did not always please Catholic intellectuals. The ‘Song of the Pelagian Heresy’ (1912) ends with praise of barley brew and a chorus of row-ti-tow, ti-oodly-ow. His ‘Heroic Poem in Praise of Wine’ (1931), which finishes on a high sacramental note with ‘Strong brother in God and last companion, Wine’, contains a passage of ferocious knockabout at the expense of water drinkers. In ‘The Microbe’ he mocks the omniscience of scientists with ‘Oh! Let us never, never doubt/What nobody is sure about!’, but scientists were surely entitled to toss this grenade back at him. Contentious and combustible, he had his dyspeptic moments, as when he tells how ‘Today’s diseased and faithless herd,/A moment loud, a moment strong;/But foul forever rolls along’, which was hardly reader-friendly. Yet for all his excesses he did his best to obey the laws of God and man and metre, most especially metre. On his death the Tablet devoted an entire issue to ‘the Catholic Dr Johnson’ (Father Martin d’Arcy). Pearce feels Belloc is entitled to the epitaph he proposed for himself fifty years earlier in ‘The Prophet Lost in the Hills at Evening’:

I challenged and I kept the Faith,

The bleeding path alone I trod;

It darkens. Stand about my wraith,

And harbour me, almighty God.

In a more playful poem Belloc had pictured Peter Wanderwide (his Balliol friends called him Peter) joshing and chaffing at the heavenly gates, being hailed by St Peter as ‘the best of men who ever walloped barley brew’, and finally being admitted to

. . . tread secure the heavenly floor,

And tell the Blessed doubtful things

Of Val d’Aran and Perigord.

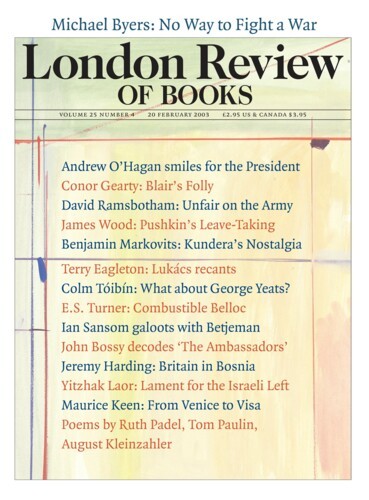

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.