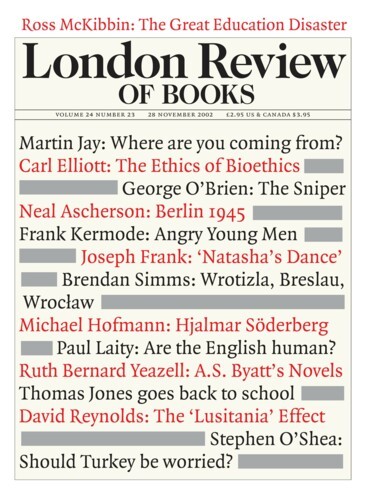

Humphrey Carpenter is a practised biographer; he can do groups as well as single persons, but he admits that this group set him a new problem, which was that he remained throughout unsure whether it really existed. The Movement (a rather localised, mostly Oxford affair) and the Angry Young Men (more London, more of the theatre) were certainly the inventions of journalists, but they took on a kind of reality when the public was induced to view the young men in terms of those inventions, and also when the writers concerned noticed that the mirror of gossip did, however distortedly, reflect them. And whatever they thought they were doing, they could hardly not know that it would give rise to large, vague speculations about the cultural condition of England.

Something similar happened to the 1930s poets, who had much to say about the condition of England, though it is said, with what accuracy I don’t know, that the four elements of the MacSpaunday group – MacNeice, Spender, Auden and Day-Lewis – were only once in the same room together; and there can have been but few occasions when the whole company of Angry Young Men was assembled. Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin and John Wain knew one another at Oxford, but had little to do with autodidacts like Colin Wilson, John Osborne and Alan Sillitoe – this last name less often mentioned in this context than might have been expected, doubtless because Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958) was published a little too late to be fitted into the fashionable grouping.

Since the constituents of his mass biography led such disparate lives and had such varied interests, Carpenter has had to be especially deft in linking one chapter to another. It happens conveniently that Wilson’s The Outsider came out just when Look Back in Anger opened at the Royal Court; and Room at the Top appeared just before The Entertainer arrived at the same theatre. To a biographer dealing with quite a large cast of characters these coincidences serve as useful junctions, giving the narrative a coherence greater than any offered by life itself.

A lot of his material is already available in single biographies, autobiographies and collections of letters, but he has done some solid supplementary work and read lots of books that have lain undisturbed on the shelf, their authors more or less forgotten. For example, the Oxford of the time boasted of characters who seemed for a while more important than the figures Carpenter principally celebrates. Bruce Montgomery, a friend of Amis and Larkin, was one such. He was a musician who called himself Edmund Crispin when writing detective stories. The upper-class detective, necessary to the genre in those days, was Gervase Fen, a professor of English at Oxford. The novels were popular; I suppose I enjoyed them too, but I’ve just tried rereading one and wonder how this could have been. It is irredeemably tedious, written with a sort of posh whimsy and containing lots of knowing quotations from the English poets. The plots are uninterestingly complicated but must nevertheless have seemed worth following. All that can be said for the books now is that they have acquired a certain archival value, suggesting more reasons why there was reason to be angry. Class distinctions are routinely enforced, the dialogue keeps everybody in his or her place, the amorous episodes are simply ludicrous. I suppose it was a sort of donnish smartness, now out of fashion, that made these books seem worth reading. What is strange is that both Larkin and Amis, who professed to admire almost nobody except jazz musicians, did admire Montgomery, though not entirely without reservations. They envied his success as a published writer. Of course there were many other writers who were targets of their tireless sledging, but they need not be envied. Montgomery was as young as Amis and Larkin, but unlike them was publishing a book a year.

Other Oxford notables who crossed the path of these aspirants included Iris Murdoch and Wallace Robson, a young don with a fearsome reputation for learning and judgment, a man whose attacks on the entire literary canon he was employed to teach were of a ferocity even Amis, by his own admission, could not aspire to. Most of the other dons were mere material for mockery. Amis quotes in his autobiography a truly hilarious parody of Lord David Cecil’s lecturing manner, admitting that he borrowed it from John Wain. I remember Wain ‘doing’ J.B. Leishman and F.W. Bateson, both of whom he respected, in a similar way. Such were the amusements of the Movement before its members became famous.

Amis, Larkin and Wain were all at St John’s but not in the same year; they shared a satirical or anyway somewhat embittered temperament, a learned love of jazz and, though only Wain would ever openly admit to it, a love of poetry. Larkin was the first to break into significant print with his two novels, and their publication partly accounted for the unflagging admiration and respect in which he was held by Amis and Wain. But these two were the funny ones: Amis was famous like Lucky Jim for his faces and the great variety of noises he could produce in illustration of his remarks, and Wain was his close rival in these arts.

I knew Wain fairly well, not only at that time but off and on for the rest of his life; my acquaintance with the other two was much slighter. He had great talents and for a while must have seemed the leader of the pack. He more or less invented what came to be called the Movement, and suddenly became quite celebrated with his audacious Third Programme anthologies, First Reading, and his novel Hurry on Down (1953). Then he began a slow and rather mysterious decline into relative obscurity. He was madly funny (sometimes it was like a madness) and had far more personality, and much more willingness to share his opinions, than the others. Quite extraordinarily well read, he could easily have chosen the life of a literary scholar. C.S. Lewis, who had been his tutor, recommended that he be asked to write the volume on Romantic literature in the big Oxford History. They turned him down, perhaps judging him to be too young or too wild, but he was in fact neither. He certainly knew enough, and his reverence for poetry would have reined him in, though he would not have smothered the subject in academic prose. If he had got that job he might have landed a university post of a more permanent kind than the junior fellowship St John’s gave him at the age of 21.

Oxford being unco-operative, he went to Reading University, and taught there boldly and conscientiously; but he tired of the routine and decided instead to conquer London. Still in touch with the other two, he chose as the first item in his first BBC programme a particularly good extract from the still unpublished Lucky Jim, which helped both the programme and the book on their way. But he and Amis fell out, and Lucky Jim (1954) rather eclipsed Hurry on Down. Moreover Wain now developed quite serious ill-health and marital problems.

Even in his sixties he could be a wildly attractive and amusing man, but in those early days he was astonishing. Not everybody approved. His professor at Reading, a man who craved admiration and influence, would have preferred not to have such a dazzler in his department. Wain made friends elsewhere in the university, among them the celebrated typographer William McCance. It was McCance who hand-printed those pretty little volumes of verse, including Wain’s own first collection, Mixed Feelings, and Amis’s second, A Frame of Mind, now, I gather, much sought after. Wain was a friend, a sincere admirer and hysterical imitator of William Empson, and his article on that poet, the last essay in the last issue of John Lehmann’s Penguin New Writing, did much to revive Empson’s reputation after his long absence in China.

Given his talent and energy, it isn’t hard to understand why he thought almost anything was possible. I remember him, in the flush of celebrity brought on by Hurry on Down, asking me why I didn’t write a novel – it was so easy, and he had not understood this until he tried. Yet his career as a novelist was nearly all downhill. Carpenter finds Hurry on Down loosely composed compared with Lucky Jim. Wain didn’t take the job seriously enough. What can’t be denied is that he wrote a lot of undistinguished fiction. My own opinion is that his finest book is the biography of Dr Johnson (1974), a labour of love greatly admired by some professional students of the subject.

A major difference between Wain and those erstwhile friends who so often put him down in their letters was that he did not share their need to pretend to hate poetry, art and music. Carpenter says that Amis took that line – for example, concealing his real love of Mozart – for fear of being accused of resembling the cultured phoneys on whom he lets Jim loose in his first novel. Even when writing to Larkin he has to apologise for mentioning the names of Schubert and Wolf. Wain would never have apologised for liking a work, and if he disliked it he would try to say why, not just sneer or pull a face.

If we are to understand the myth of the Angries we have to admit that Wain added less to it than Amis, partly because he was, as time revealed, a lesser novelist than Amis and a lesser poet than Larkin; but also because he took less pleasure in snarling. He always struck me as being as close to a completely honest man as you could meet, a man who cared about the views of other people and about the people themselves. Snarling was a much more useful contribution to a cult of Anger.

Although literary journalists might still have continued to develop their Movement theme – mostly a matter of post-Empsonian verse forms and anti-Modernism – they must have been pleased when the other, less Parnassian writers came into view. There would have been no revolutionary rage or aspiration for the Oxfordians to join in had not Wilson, Osborne and his associates, and later John Braine stormed onto the scene. These men had little in common with the Oxford group, except that, as Carpenter is quick to point out, everybody concerned cared a lot more about getting on than about changing the culture. Much as he admires Lucky Jim, he condemns the hero’s selfishness and allows the imputation that it reflects the author’s. And Braine’s Room at the Top, a huge success that he was never able to repeat, makes a virtue of pure selfishness. Later Braine became a member, along with Amis, of the Bertorelli lunching club, the Fascist Beasts, whose members were famous for professing fairly extreme right-wing politics. Both, of course, had only lately moved over from the extreme Left. (Here again Wain was different: he was voting Tory in the early 1950s, when Amis was still a member of the Party.)

It was Osborne, doubtless no less selfish than the others, who supplied most of the anger and was most audible, because he was so good at invective and found a theatre to demonstrate his power. His chapter in Tom Maschler’s Declaration (1957) was thought bold to the point of outrageousness: he even attacked the Royal Family. Angus Wilson, reviewing Declaration without much enthusiasm, acknowledged the reality of Anger, remarking that ‘nobody under fifty . . . can sincerely feel content with the present state of the arts. We are all waiting for something great to turn up. And . . . we are often led to speculate whether England’s artistic death does not reflect a wider sterility in the social and political structure of the country.’ Wilson doesn’t seem to think the cure would come from the contributors to Declaration, for he treats them as symptoms, not healers.

No doubt there did exist what Osborne called a ‘climate of fatigue’, not yet dispelled even when the war was long over and rationing had at last ended. Gloom about the Bomb, Suez and Hungary displaced memories of the war. Some of the angry young men were old enough to have seen some military service and experienced the hierarchical snobberies and enforced deference which were a painful extension of rigours still normal in civilian life at the time. They could now see these conditions for what they were and, having imagined that they had left them behind in the Army, did not like finding that they remained in force, if slightly weakened. Their resentment was expressed in various ways, and so were their hopes of improvement. Wilson was hailed as the restorer of our lost intellectual pre-eminence, and Osborne, once Look Back in Anger had settled in, as the man who worked the miracle and revived a moribund theatre. The Entertainer does manage to be a transparent allegory of both social and theatrical decay. Some of the recent obituaries of Joan Littlewood have suggested that she should have had the credit for that renaissance. These matters may be, indeed usually are, overdetermined, but simpler explanations are handier, and in recent years Littlewood seems to have got left out of the story for ease of telling.

In the end the value of these writers has to be considered apart from their effect on the ‘social and political structure of the country’, just as the value of Wordsworth cannot always be dependent on his enthusiasm for the French Revolution. Amis survived because he was a good and idiosyncratic stylist, Larkin because he made himself the finest poet of his time, though at the moment an irrelevant dislike of his personality, as it was presented in Andrew Motion’s biography of him and in his correspondence with Amis, seems to have dulled understanding of this point. There are other names, loosely associated with Anger – Sillitoe, whose Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is surely as remarkable an achievement as any I’ve mentioned; and Keith Waterhouse, whose Billy Liar (1959) fitted the pattern of youthful male revolt so well that his quite different but still excellent earlier novel, There Is a Happy Land (1957), which didn’t fit, was soon forgotten.

Waterhouse went on to be a satirist. Carpenter, who has written a book about the satirists of Beyond the Fringe, That Was the Week That Was and the Establishment Club, believes that they ‘managed effortlessly to effect a change in British society that the Angries had failed to bring about’. It was to TW3 that Edward Heath ascribed ‘the death of deference’. An alarmist response, surely; anybody can think of ways in which deference is still with us. Many even continue to think it has its point. In any case Carpenter’s endorsement of satire as its enemy is probably too enthusiastic. Perhaps we still need a revolution. If it happens it may well be a slow and bloodless affair, brought on by writers anglophone but not native British, working within those political and social structures and slowly changing the ways we think and feel about them.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.