Winter comes but nearly all the year to the city of Tromsø, a wind-lashed port standing precariously on the western coast of Norway, 69.7 degrees North – beyond the Arctic Circle. The inhabitants are proud of their small city, inaccurately called the ‘Paris of the North’ or, more realistically, ‘the Gateway to the Arctic’. It’s a quiet place, bleached by the cold, where everything flaunts its latitude, from the Arctic Hotel to the Arctic Cathedral. The landscape is beautiful and severe: vast grey slabs of rock slamming into the ocean, decorated with swirls of thick mist and dustings of snow. It’s dark most of the time, and when the sun does appear, it’s an anaemic blur, too sickly to drag itself above the horizon for long.

I arrive on a plane from Oslo, swooping low over the mountains. The road from the airport winds up and down a hill, past sparse clusters of trees and houses coloured with a variety of wood stains – yellow, green and red. The fjord is overcast, and the mountains rise bleakly above. I pass a series of dirty houses, their windows blank. Tromsø’s centre consists of a main street – dotted with wooden houses and dull concrete high-rise hotels – some arterial roads running down to the harbour and a large wooden church. Parts of the harbour struggle to appear quaint, but most of it is stoically functional, serving lumbering ferries and trawlers.

I’ve come to this frozen town because of the Norwegian explorer, scientist and Nobel Prizewinner Fridtjof Nansen: a key figure in a book I am writing about ideas of Nordic purity and the myth of Ultima Thule. Thule was the ‘most northerly land’ of classical antiquity, a mysterious place, untouched by humans, where immortal tribes were thought to live. Nansen intertwined the Thule myth with his writings on Polar exploration, and later wrote a book suggesting that Norway was Thule. Within a few years of its publication, however, the Thule myth had been adopted by proto-Nazis in Germany, including Hitler and Alfred Rosenberg. The Thule Society was convened in 1919; its rituals included telepathic communication with Nordic immortals. Nansen certainly wasn’t a crypto-Fascist, but his ideas about Nordic purity were irreparably tainted by the Thule Society; ‘Thule’ now serves as Internet-Fascist shorthand for ideas of Aryan supremacy and the pure North.

The sun is sinking slowly towards the fjord as I arrive, not long after lunchtime, at the Ishavshotel (Arctic Hotel), which stands by the quayside, disguising its opulence behind a grimy orange exterior. At first glance, it looks like a harbour office, crammed with maritime bureaucrats handing out mooring permits to trawler captains. But the interior lavishly mingles Russian and Scandinavian decor – gold furnishings and St Petersburg glitz with touches of Nordic sail loft. From my room I can see across the fjord towards the Arctic Cathedral, which looks like an immense pile of blocks of ice. The hotel dining-room curves towards the sea, and a long table offers herring, salmon, eggs, vegetables and cold meat. Above the smörgåsbord, there’s a mural of splashy images of people fishing, whaling, sealing and reindeer herding. These, now variously imperilled, are the traditional trades of northern Norway. Fishing stocks are low; reindeer herders have been threatened with legal action by landowners who resent the migrant hordes; bans on whale exports left the whaling ships abandoned – in July whale meat was exported (to Iceland) for the first time since 1998. The ban, Norway argues, is unfair on the whalers whose livelihood depends on exports. They also say that the minke whale population is not endangered.

For the Norwegian Polar explorers of the last century, Tromsø was the departure lounge, the last stop before the endless ice. I had thought the city would be reaping the benefits of the Polar industry – the biopics, the biographies, the inexplicable determination of Kenneth Branagh (of Shackleton) to out-act John Mills (of Scott of the Antarctic), the retellings of modern legends about the explorers freezing and dying and writing poetry as they did so. But Tromsø is almost empty. There seem to be hardly any tourists, though I am told by a smiling woman in the Tourist Information Centre that 16,900 German and 16,300 Japanese tourists visit every year. The Japanese come in search of the aurora borealis, and spend the nights in devout observation of the sky. By day, they are presumably asleep in their hotel rooms. The woman adds that Tromsø has about 60,000 permanent inhabitants, but concedes that you wouldn’t guess it, looking at the shuffling few outside.

Few of the city’s inhabitants still make their living from fishing and farming. Most work in shops or offices, or in the restaurants serving fish at exorbitant prices. But the quayside is busy: there are rusty Russian trawlers tied up for the day, Russian voices shouting orders through megaphones, and hoots from foghorns. The Russians come here from Murmansk; you see them ambling to the quayside bars in the evenings. On the first night, I follow them into a mat og øl hus (‘food and beer house’) called Skarven, a substantial stone building at the water’s edge. There’s a fire roaring in a grate, and dozens of stuffed animals and birds stare glass-eyed from every beam and shelf. It’s midnight on a Wednesday, and the bar is as sweaty and garrulous as Soho on a Saturday night. Russian voices mingle with guttural Norwegian; there’s a burly queue at the bar for refills. My tentative request for a glass of wine is met with stony incomprehension. ‘Only beer,’ the barman grunts.

In the morning, the sun lying low across the fjord, I set off to delve in the Polar Museum. Nansen left Tromsø for the North Pole in 1893, and emerged three years later on Franz Josef Land. He had failed to reach the Pole, but had made an advance of 170 miles on previous attempts. In 1897, he wrote an account of his journey, Fram over Polhavet (literally ‘Forward over the Polar Ocean’), which appeared in English as Farthest North. He took his epigraph from Seneca: ‘A time will come in later years when the Ocean will unloose the bands of things, when the immeasurable earth will lie open, when seafarers will discover new countries, and Thule will no longer be the extreme point among the islands.’

Humanity, Nansen said, was discovering so much of the earth that the mythical land of Thule might become a mere stopping-off point, en route to somewhere still further north. It was a potent myth to summon, having rumbled on through history, from the land’s first sighting by Pytheas in the fourth century BC. Pytheas claimed that his ship reached a region in which ‘there was no longer any distinction of land or sea or air.’ Frightened by the engulfing fog and semi-solid water, he turned his ship around and went home to Marseille, to relay tall tales of the British Isles and beyond. Strabo, Geminus of Rhodes, Pliny and Pomponius Mela later speculated about the existence of the island. Thule became entwined with the myth of the Hyperboreans – according to ancient geographers, an immortal tribe who lived in the far North, and enjoyed days of unending joy and health.

Nansen thought that the western coast of Norway might have been the land Pytheas had called Thule. In a passionately argued, slightly strange book, Nord i tåkeheimen (1911) – translated into English as In Northern Mists – Nansen proposed that

Pytheas may have sailed north from Shetland with a south-westerly wind and a favourable current towards the north-east, and have arrived off the coast of Norway in the Romsdal or Nordmøre district, where the longest day of the year was of 21 hours . . . From here he may have sailed northwards along the coast of Helgeland, perhaps far enough to enable him to see the midnight sun, somewhat north of Dønna or Bodø.

Somewhat north of Bodø would include the area around Tromsø.

This is highly convenient for me, as it makes me think I might be able to avoid catching a juddering seaplane out to the Norwegian Arctic territory of Spitzbergen, another candidate for the mythical land. Walking through Tromsø, lashed by a frigid wind, I wonder how Nansen seriously expected the world to believe that this was the tranquil land of Thule. But the merging of sky, land and sea which deterred Pytheas is a conspicuous feature. Under the constantly accumulating snow, everything becomes monochrome – and the snow is a beautiful, idyllic white, continually refreshed before it can turn to slush. I walk across a scenic stretch of the harbour, past low wooden sail lofts, and a collection of antiquated fishing boats, a mass of polished planks and intricate rigging. In the summer, a sign says, fishing boats can be hired for an authentic taste of the old North. Today, the halyards clank against the masts, and there’s no one on deck. This solitary shambling over icy streets suits the bleak art of Nordic myth-hunting, but there’s something depressing about the grim functionalism of these Arctic towns. Small, oppressive box houses, low-slung roofs, everything battened down in readiness for the inevitable storm. Set against immense rocks, a vast sullen sky and bottomless fjords, Tromsø inspires a mild agoraphobia which I’ve experienced before, wandering around these parts. The hugeness of the natural surroundings and the compressed ugliness of the buildings start to weigh me down, making my preoccupations seem faintly absurd.

By the time I get close to the Polar Museum I’ve begun to understand why Nansen always stares out of photographs with an expression of such annihilating melancholy. The temperature’s around –10 °C, which is hardly exceptional for the season. But this sort of cold means that the body is constantly demanding small compensations – a cup of hot chocolate, a packet of dried fish, a warmer hat. It’s impossible to walk on the ice-glossed street without staring downwards, nervously watching your feet slide across the frictionless surface. Slightly wet shoes – caused by a sudden slip off the pavement and an ignominious landing in a patch of snow – reduce my wants to a simple, furious desire for dry socks. I struggle on, like a bent-backed babushka.

The museum, which I reach eventually, is full of mundane objects, fascinating only through historical accident: the boxes of matches, blunted knives and frayed leather boots enlisted long ago in the struggle across the indifferent ice. I follow the trail of the other tourists, who pause dutifully at every exhibit, lingering over the pictures of explorers aiming shots at seals, shielding their eyes against the sun. Away from the sledges and skis and navigation equipment, I stop at a dusty glass cabinet, containing a pocket-sized, brown leather copy of Frithjof’s Saga – a tale of chivalric courage and frost-bitten love, adapted from an Icelandic saga by Esaias Tegner in 1827. The book is flattened out under the glass at its first page, on which Roald Amundsen wrote: ‘This book came with me on all my journeys.’ Nansen, a ‘Frithjof’ himself, could recite long passages of the saga by heart, and enjoyed the occasional Nordic flourish. ‘Our ancestors, the old Vikings, were the first Arctic voyagers,’ he wrote, proudly, in Farthest North. In another passage, he imagines the North Pole as a giant from a Viking saga: ‘wrapped in his white shroud, the mighty giant stretched his clammy ice-limbs abroad, and dreamed his age-long dreams. Ages passed – deep was the silence.’ It was as if Nansen saw his Arctic exploration as filling in the blanks on ancestral maps, rediscovering imaginary Viking worlds – Nivlheim, Helheim, Trollebotn.

Nansen made his claim that Norway was Thule in 1911. It was a time of national regeneration – the country had gained independence from Sweden in 1905, after centuries of colonisation. Nansen had acted as Norwegian Ambassador to Britain around the time of Independence, and had put in many hours at Court, canvassing support for the new country. His Thule theory might be seen as a patriot’s gift to the new nation – retrieving its roots in ancient history as the essential wilderness, the untouched North.

His theory was attractive later on to German nationalists struggling to come to terms with defeat in World War One. Under the leadership of Rudolf von Sebottendorff, a pseudo-aristocrat, the Thule Society met in secret in Munich. Its symbol was a dagger superimposed on a swastika. The combination of mysticism and megalomania was attractive to a number of future Nazis: as well as Hitler and Rosenberg, Rudolf Hess and Anton Drexler also turned up at meetings. But the Society soon fell apart amid factions and recriminations, and von Sebottendorff moved to Switzerland. Returning to Germany in the early 1930s, he irritated the Nazi high command by insisting that his society had been the inspiration for National Socialism and was briefly interned before being sent to Turkey, where he worked for German Intelligence. He might have been right, however: by this time Rosenberg was supervising the spiritual and ideological training of the National Socialist Party.

The Thule legend was adapted for eugenic ends when the Germans occupied Norway in 1940. The Norwegian branch of the Lebensborn programme encouraged interbreeding between Norwegian women and German men – hoping to enrich German stock with Nordic genes. While the occupation lasted, the German-Norwegian krigsbarn (‘war children’) were coddled as the privileged Aryan heirs of the Third Reich. They included Anna-Frid (‘Frida’) of Abba, whose father was stationed in the northern town of Narvik at the end of the war. But after the Nazis left Norway, some of the mothers were rounded up and interned on an island in Oslo Harbour. The young Frida moved to Sweden with her family.

Many of the krigsbarn were placed in children’s homes; others were deemed mentally defective and put in asylums. The myth was reversed: the krigsbarn, under the Nazi regime a perfect combination of races, were perceived by postwar Norwegians to have been tainted by their parentage. According to official figures, there are now nine thousand krigsbarn in Norway; the real figure is probably much higher. Many feel that their lives were ruined by their treatment. Siss Oustad of the Krigsbarnforbundet Lebensborn says: ‘Many were put in children’s homes, raped, misused, treated badly, and punished for nothing. This happens today in other wars; our point is that the Government made this happen. They thought that we couldn’t be normal people. The doctors and clergymen agreed. They said it was easier to raise rats than these young people.’ On 1 January 2000, The Prime Minister, Kjell Magne Bondevik, officially apologised for the ‘suffering endured by the krigsbarn’. But 122 of them are currently seeking compensation from the Government. If they fail, the krigsbarn intend to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights. Meanwhile the Government has sponsored, to the tune of six million kroner, a three-year research programme to find out more about the conditions the children grew up in. A report will appear in 2004.

At the time when Nansen took Seneca’s epigraph as the rallying cry for his Polar pursuit, the mention of Thule suggested a challenge to the daring explorer, a trip into strangeness. The 20th century distorted the myth, and Norway emerged from the Second World War jaded and humiliated. Knut Hamsun, one of the country’s finest writers, who came from an area just south of Tromsø, openly sympathised with the Norwegian National Socialists and Hitler during the war. There was an excruciating moment in his trial for treason, when he defended himself on the grounds that ‘we were led to believe that Norway would have a high, prominent position in the great Germanic global community which was now coming into being and which we all believed in – to a greater or lesser degree, but everyone believed in it. I believed in it, that’s why I wrote as I did.’ He was judged to have ‘permanently impaired’ mental faculties, and fined.

The Thule legend can never be innocent again, just as the Arctic will never again sleep spotless under a mantle of pure ice. As I follow the slow-moving tourists out of the Polar Museum, into the gathering dusk, I stop in the foyer to buy the obligatory postcard of Nansen. He’s dressed in Arctic furs, sporting a vast moustache and a stoical expression. In the 1920s, he held various prominent positions in the League of Nations, including High Commissioner for the Repatriation of Prisoners of War, helping mainly to return Russian prisoners held in Germany and German prisoners held in Russia. He worked to alleviate the famine that hit Russia in 1921; when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 he used the money to establish farms in the Volga region and Ukraine. The Prize recognised especially his part in devising the Nansen Passport, which supplied stateless refugees with identity and travel papers. In his biography, Ronald Huntford suggests that Nansen came to be perceived within the League of Nations as a malleable figurehead, manipulated equally by the Americans and the Russians. A recent biography by Per Egil Hegge, however, suggests Nansen knew far more about what he was doing, especially in his negotiations with the Russians, than was previously thought. He died in 1930.

Leaving the Ishavshotel, I drive out to another propeller plane, past the low rows of houses, and up the hill that stands behind the town. The airport is snowbound; the runway is closed for sweeping. Waiting in the plane for the de-icing vans to pass by, I look back across the fjord, towards the lights of Tromsø. A pinkish twilight has settled over the town and it looks almost beautiful.

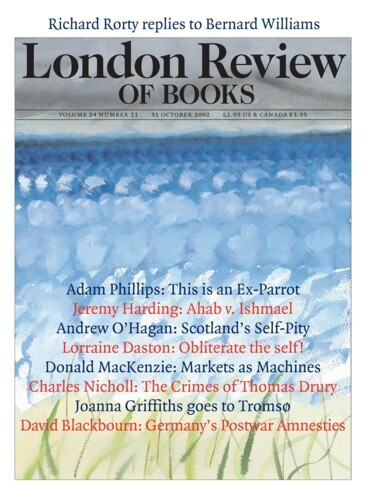

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.