‘My friends, my friends, I say to the teacups and spoons. Such intense love for Puss – more and more,’ Iris Murdoch wrote in her journal. It was the summer of 1993. Her 25th novel was just being published, and she was working at her last, Jackson’s Dilemma. Who was Jackson? Puss asked her, but she could not tell. ‘I don’t think he’s been born yet,’ she said, at which Puss, accustomed to finding her amusing, was amused. The beginning was too mild, too like the customary affectionate nonsense of their married life, for alarm. It was the autumn of 1993. ‘Find difficulty in thinking and writing. Be brave,’ she wrote, and was. The near edge of the unknowable, never well fixed, advanced. It was 1994. There began to be bewilderment in public settings, and although the bewilderment belonged increasingly to others, enough remained (it was 1996) for grief. It was 1997, the year her Alzheimer’s was diagnosed. ‘My dear, I am now going away for some time,’ she wrote. She wrote, ‘I hope you will be well,’ trailed off, began a second sheet of paper. ‘My dear, I am now going away for some time. I hope you will be well.’ She began a third.

Although it is by no means always the case with Alzheimer’s that illness uncovers truth, it seems both to Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley (‘Puss’), and to her biographer, Peter Conradi, that it did so here. In their view Murdoch’s advancing illness, crumbling away language and reason, laid bare in her an essential impulse toward love. As words broke up, it was the vocabulary of love and delight that survived the longest. When those words followed the rest into oblivion, the ways of affection, gratitude, interest still remained, as if they were what was most deeply rooted in her nature, the truest part of her, until there was nothing left of her at all. She could say ‘I love you’ when other sentences were too hard to put together, and after she had forgotten the words ‘I’ and ‘you’ she remembered ‘love’. Bayley tells of the day she put a hand on his knee and said to him, ‘“Susten poujin drom love poujin? Poujin susten?” I hastened to agree, and one word was clear . . . She knew what she meant even when there is no meaning, and there was in that word.’

She was mysterious, even unknowable, but yet, though unknowable, still capable of being known to be good: a formula worthy of a theologian. It had always been so; the failure of language simply made the paradox more troubling. Writing in his volumes of Murdoch-centred memoir Iris: A Memoir and Iris and the Friends, Bayley noted the degeneration of her words into babble even as he refused to doubt her meaning when that meaning seemed to be her love for him. Though at some point the gesture towards speech must cease to count as speech, it is nonetheless hard to know how else to regard it. Her ordinary babble, he remarked, ‘seems normal to her and to me surprisingly fluent, provided I do not listen to what is being said but apprehend it in a matrimonial way, as the voice of familiarity and thus of recognition’, and in company she continued to wear her usual expression of ‘courteous but faintly amused interest’, listening, offering responses, outwardly quite normal – an illusion that lasted until one came close enough to hear what she was saying. What sounded like real words, even real phrases, ‘eerie felicities’, as Bayley called them, still sometimes came out of her mouth. It is impossible to know what such things mean when they come from someone for whom words – particular words with particular meanings, as distinct from the cries one makes in response to pain or delight or the cries of others – seem no longer to function. Are they remnants, are they simulacra of meaning? Are they something else entirely? After Murdoch had lost the capacity for articulate speech, she nevertheless told Conradi that she was ‘sailing into darkness’ and exclaimed as a friend bathed her: ‘I see an angel. I think it’s you.’ For Bayley the supposition that these were messages from inside the disease, signifying the survival of ‘a whole silent but conscious and watching world’ trapped within what Alzheimer’s had made of his wife, became at last too painful to credit.

In Bayley’s experience of an understanding too fragile, too unlikely, or too disconcerting to be pressed, any reader of Murdoch’s novels will recognise a version of the perplexity, the maddeningly seductive illusion of intelligibility and intelligence, that was a speciality of the younger and still articulate novelist. Murdoch subjected both her characters and her readers to what amounted to large-scale versions of something not unlike ‘Susten poujin drom love poujin’. From the beginning of her literary career she organised her fiction around the sensation of understanding that defied intelligible expression, the feeling of being overwhelmed by an insight that owned no specifiable content, the apprehension, well known not merely to lovers of the Gothic and the sublime but to lunatics of several varieties, that all this somehow meant something. The trick (it felt like a trick in her unhappily numerous weaker novels) worked until one realised that of course it did not, and that it was language that had abandoned sense rather than the other way around. Indeed, even in the handful of novels that earned Murdoch the right to be taken seriously as a contender for greatness, she set her ecstatic visions to fail. And if the narrative of a protagonist’s approach to the verge of what seemed cosmic revelation was characteristic, so too was the scene of headachy confusion, semi-amnesia, and irritable incredulity that was sure to arrive in its train, like a migraine after its aura, or the aftermath of a fit.

Her subject is love: obsessive, incestuous, adulterous, selfless, blind, lost and unlikely and remembered, its objects so various and so fungible, its appearances so fantastically symmetrical, its developments so entirely subject to accident on the one hand and the rigorous necessity of permutation on the other that, for all the damage it inflicts, the reader soon learns to regard it with something approaching amused disbelief. More sceptical readers might doubt that it is love at all. Those among her principal characters who suffer from it use a rhetoric in which the erotic is indistinguishable from the metaphysical or even the eschatological. In any other book a character who exclaimed that love promised salvation and its loss damnation, that the success or failure of romance raised the lover to heaven or cast him into hell, would be regarded by the reader as guilty of improper and rather tired exaggeration. But a Murdoch character means what he says when he announces that to be looked at by his beloved is like being seen by God, that his ‘black certain metaphysical love’ is ‘its own absolute justification’, or that ‘this is something very absolute. The past has folded up. There is no history. It’s the last trump.’ He is in the grip of a spiritual energy aimed at ultimates and absolutes partly Platonic and partly Christian. He believes (between intervals of hellish doubt) that love will redeem his sufferings, annihilate the obscure, guilty confusion of his finite chance-harried being, sublate his will into a necessity that governs accident and ordains significance. His old self will fall away, together with the vexation of innumerable wearying claims on his attention by contingent beings whom love has not so justified, and he will be saved, perhaps even deified. All shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well.

The desire to be innocent again, the desire to be redeemed, the desire that all this should mean something: in Murdoch’s world, these are the great temptations and the great sources of spiritual corruption, particularly but not only when they offer themselves as cover for less acknowledgable motives. The loss of innocence feels to a Murdoch character like an injury for which he may reasonably demand a reparation not to be distinguished in its effects from revenge; his inability to bear his own guilt seems to require an act of self-restoration – or self-annihilation – that risks repeating his crimes. A character is cruel to others in proportion to the intensity of his lust for salvation: the myth of his own suffering and redemption obliterates everything it cannot absorb, as everyone around him is classified as an instrument of his salvation, an obstacle to his salvation, or an irrelevance, and used accordingly. Murdoch remarks through one of her characters that guilt ‘isn’t important, it may even be bad. One must just try to mend things, do better. Why cripple yourself when there’s work to do?’ But this is not what her protagonists want to hear. Whenever in Murdoch someone decides to become a ‘clean man’, bad things follow.

Murdoch denied that she used her novels to stage her ideas, pretending to ‘an absolute horror of putting theories or “philosophical ideas” as such into my novels’, insisting: ‘I might put in things about philosophy because I happen to know about philosophy. If I knew about sailing ships I would put in sailing ships; and in a way, as a novelist, I would rather know about sailing ships than about philosophy.’ This is disingenuous. The matters that obsess her protagonists clearly obsess her and her obsessible readers as well. Their temptations are hers and ours. The arguments about morality and religion Murdoch gives her characters, particularly those characters who represent the unegoistical mode of goodness despised by her clever protagonists as spiritually timid, repeat the same points she makes in her philosophical essays. They may matter even more in the fiction. For though she declares herself ‘reluctant to say that the deep structure of any good literary work could be a philosophical one’, she declares in her next breath: ‘For better and worse art goes deeper than philosophy.’

The pleasures of the didactic are underrated. Still, it is an odd sensation to find oneself flipping impatiently past seductions, suicide pacts, levitations, sea monsters, exhilarations, exaltations in order to get at the good stuff – the didactives – and odder still given the sense of them. For what happens is that one by one the moral and metaphysical temptations are dismissed as unreal or unmeaning. Justification, necessity, forgiveness, salvation: there is no one to authorise such things or to recognise them. There is no ‘magical rehabilitation’, no machinery for the redemption of suffering. An essential need to adore confronts an emptiness. Turning the second commandment (‘Thou shalt have no other gods before Me’) against God himself, Murdoch guards this emptiness jealously, as if on his behalf, except that he does not exist, and even if he did he would be unworthy to occupy that space. (She guards the absoluteness of the irremediable with a like fierceness.) It is the ontological proof turned inside out: ‘No existing thing could be what we have meant by God. Any existing God would be less than God. An existent God would be an idol or a demon.’ Belief is evacuated of its content and yet required to stand. Pure faith would be faith in emptiness. Murdoch quotes Simone Weil quoting Valéry: ‘The proper, unique and perpetual object of thought is that which does not exist.’ If one is to be good it must be ‘for nothing’.

‘Absolute for-nothingness’ transvalues the ordinary world of ordinary things and people, now to be loved, or at least seen, in all their contingency, which for Murdoch means in all their indifference to our purposes. These objects of potential attention (attention is love) remain particular, distinct, untheorised. Nothing is privileged, not because nothing matters (although nothingness does matter) but because everything does; on the other hand, while everything matters, nothing counts, because there is nothing for it to count towards. Yet because nothing is privileged, nothing is beneath notice, nothing is annulled. Dead leaves, scraps of paper, mismatched socks, even (after she became ill, when she sought to find homes for them) dead worms and cigarette butts: such things had for Murdoch, as they did for those of her characters with whom she shared a habit of tenderness towards forlorn objects, ‘all a life and being of their own, and friendliness and rights’. In 1949 Murdoch wrote: ‘Had a curious hesitation today about burning a sheet of paper. There is a sort of animism which I recognise in myself & in my parents. We are surrounded by live & rather pathetic objects.’ And in 1992 (quoting Plato quoting Thales): ‘All things are full of gods.’ If nothing in particular must be adored, everything may be.

Such adoration often wore a sensual aspect. Like anything else of importance (goodness, understanding, God), adoration (or love, as we might as well call it) is plagued by false semblances. But in Murdoch’s conception of love, the difference between the real thing (the selfless attention to another, the ‘perception of individuals’, or ‘the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real’) and the counterfeit (egoistic fantasy that blots out the reality of its object) is independent of any distinction between the physical and the spiritual. ‘Stuart was not dismayed by his sexual feelings about the boy,’ we read of a rare ‘good’ Murdoch character meditating the accusation of paedophilia a child has just levelled against him: ‘He had, or had had, more or less vague sexual feelings about all sorts of things and people, schoolmasters, girls seen on trains, mathematical problems, holy objects, the idea of being good. Sex seemed to be mixed into everything.’

PPeter Conradi was a close friend of Murdoch’s in the last few years of her life and a support to Bayley as he cared for her. He had known her for many years before as a beguiling but terrifying figure, and had published a wise and meticulous study of her novels, The Saint and the Artist, in 1986; his valuable selection of her essays, Existentialists and Mystics, appeared in 1997. Iris Murdoch: A Life, to which Murdoch gave her consent, is, like Bayley’s double memoir, the work of manifest affection. But where Bayley sets his marriage between his readers and his wife, distracting us from any disapproval of Murdoch by the subtle display of his own eccentricities and acting by right of husbandly feeling to suppress an occasional awkward fact, Conradi effaces himself in the presence of his subject, allowing his material to present itself as if neutrally. His purpose, he concedes, is at least partly defensive. Recognising the potential for scandal in some of his material, Conradi wants to ensure, by managing the task himself, that its first full-length presentation is both fair and sympathetic. Yet while contending that her good deeds would fill a book, he gives us not that book but another, one in which she bears a more ambiguous character.

Murdoch was born in Dublin in 1919, the only child of a gentle, spider-rescuing, nonsense-loving Scots-Irish father in the Civil Service and a mother who gave up training for a career as a singer when she married. The family left for London while Murdoch was still a baby. In later years a cultivator of exiles and refugees, Murdoch would speak of her family as ‘wanderers’ and say: ‘I’ve only recently realised that I’m a kind of exile, a displaced person.’ Despite what the slight, artfully preserved brogue of her adulthood might have suggested, her experience of Ireland was derived largely from summer holidays there. Her parents adored her. Looking back at her childhood, she would describe it as ‘a perfect trinity of love. It made me expect that, in a way, everything is going to be like that, since it was a very deep harmony.’ At the age of five she began her education at the Froebel Demonstration School, where imaginative lessons and games of Knights and Ladies absorbed her. Lacking a brother, she invented one in her ninth year, doing such a good job of it that her lifelong friend Miriam Allott was shocked to learn in 1998 that he had been an imaginary being; this brother, the innocent forerunner of the invidious, fantasy-ridden siblings she would invent later, was the basis for her first stories. When she was 12 her parents removed her to the small, conscientiously unsnobbish Badminton School to be a scholarship student. (Indira Gandhi was there, briefly, at the same time.) If Froebel had awakened a taste for quasi-medieval romance and its thrilling confusion of the erotic with the spiritual that would later prove so insistent a problem in her fiction, Badminton developed her interest in ethics and politics. Within a year of her admittance she had decided she was a Communist; not long afterwards she had her first religious experience and was confirmed into the Anglican Church. Aside from an early episode that prompted a fellow student to form a society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Iris, Murdoch was popular with everyone. She was a model student, notably kind, interested in and talented at everything, throwing herself into painting and hockey and poetry and Greek and Latin and debating and drama. She was a particular favourite with the head, Beatrice May Baker (‘BMB’), a high-minded, free-thinking advocate of good works, cold baths, sex education and the League of Nations (as which organisation she came disguised to a Christmas party one year) who began with Murdoch a conversation about right and wrong that would last until the older woman’s death. From BMB and her regimen (which included tuition in the League of Nations Summer School in Geneva) Murdoch absorbed enough political and especially pacifist sophistication to win prizes in the League of Nations essay competition two years in a row, beating the young Raymond Williams the second time around. From BMB Murdoch learned, too, an admiration for the Soviet Union which the evidence of Stalin’s purges and show trials could not shake; her Soviet sympathies outlasted her pacifism by some years.

It was only in retrospect that her school years seemed dull. Murdoch went up to Somerville College, Oxford in 1938. As at Badminton, she wanted to try everything. Now there was far more to try and more at stake in doing so. She knew already that she wanted to be a writer and had thought she wanted to study English. From English she turned to classics. Her teachers – particularly Eduard Fraenkel, who taught her Horace and the Agamemnon and led discussions on suffering and violence, and Donald MacKinnon, whose subjects were theology, moral philosophy, and the dangerous appeal of pain – were of enormous importance to her intellectually (what she studied with them would remain a matter of essential concern in the next several decades of her career) but also emotionally. MacKinnon, she declared, inspired the kind of reverence one might have for Christ, and she proceeded to model her manner on a bizarre few of his mannerisms. In Fraenkel’s seminars she was nearly as impressive a presence as Fraenkel himself. Yet not even these men fully absorbed her attention, or their fields her ambition. She loved jazz, dancing, drama, political debate; she wanted to be an archaeologist, a Renaissance art historian, a painter; and possibly as early as 1938 she joined the Communist Party. She met now many of the people who would matter to her for the rest of her life: an abundance of friends and (the two categories overlapping) an altogether absurd and certainly unsummable quantity of admirers. The philosopher Philippa Bosanquet was perhaps her closest friend from that period; the relationship was injured by Murdoch’s romantic treachery towards both Bosanquet and M.R.D. Foot, the man Bosanquet would marry, but recovered (to Murdoch’s guilty relief) when the Foots divorced. She was close as well to the linguist Frank Thompson, who would enlist in 1939 and die in 1944, a volume of Catullus in his pocket, while leading a group of Bulgarian partisans, the victim, almost certainly, of political treachery later unravelled by his younger brother, E.P. Thompson. He seemed to her at least retrospectively to have been the first man she loved enough to have married. His loss, unlike Philippa Foot’s irreparable, remained a source of grief to the end of her life.

With her First in classics, Murdoch left Oxford in 1942 to spend the next three years in London, working first at the Treasury and then, in 1944, in an unsuccessful effort to escape London and romantic entanglements, at the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Late in 1945 UNRRA sent her to the Continent to work with war refugees. Her ten months in Belgium and Austria, spent mostly, as she later said, ‘simply preoccupied with feeding people’, steadied her conviction that ‘goodness is needful, one has to be good, for nothing, for immediate and obvious reasons, because somebody is hungry or somebody is crying.’ In Brussels she met Sartre and in Austria captivated Queneau, two writers crucial for the development of her work. Though Sartre: Romantic Rationalist, the first of her books to be published and her first major act of resistance to the existentialist emphasis on the heroic will of what she would later call ‘the lonely self-contained individual’ (the human counterpart to Kant’s ‘pure, clean, self-contained’ art), was still eight years off, and Under the Net, her Queneau-flavoured first published novel, nine, she had in effect already begun her life as a writer. By the time she met Sartre and Queneau, she had written at least two of the four or possibly six novels that preceded Under the Net (she destroyed them in the 1980s, hence the uncertainty about their number).

In 1946 she was in England again, reading, experimenting with Anglo-Catholicism, trying to recover from the devastation of yet another wave of love affairs. She spent a year on a studentship at Newnham College, Cambridge, balancing uneasily at the outermost edge of Wittgenstein’s circle, friendly with some of his disciples but not with the man himself, before accepting a philosophy tutorship at St Anne’s College, Oxford in 1948. Here too she was philosophically eccentric, out of sympathy with the dominant analytic philosophy and more inclined towards a difficult-to-define spirituality than seemed quite fitting. She was, in Isaiah Berlin’s words, a ‘lady not known for the clarity of her views’. It didn’t matter. By now, reading Simone Weil, rereading the formerly despised Plato, reconsidering Christianity, and moving in the direction of an interest in Buddhism, she began to form a new intellectual centre for herself: it would be goodness, selflessness, and attention to others that she would study.

These qualities, only intemittently evident in her romantic relationships of the period, did matter in her relationship with Franz Baermann Steiner. Like so many of Murdoch’s close friends, Steiner was a Jewish refugee, his scholarly interests embracing holiness and the taboo. After he died in 1952 at the age of 43, possibly in an embrace with Murdoch (so Conradi conjectures), Murdoch exclaimed that she had ‘lost, by death, the person who was closest to me, whom I loved very dearly, whom I would very probably have married, if things had gone on as they were going’. She looked for consolation to Elias Canetti, the dark counterpart to Steiner but also, in his attentiveness, his promiscuity and his power to enslave his lovers, a counterpart to Murdoch herself, or to what she might have been on the verge of becoming. He may have been the person who launched her career by sending the manuscript of Under the Net to Viking Press. He may also, Conradi suggests, have taught her by example what evil was.

From the cruel and cruelty-inducing tangles of Canetti’s erotic affairs, Bayley rescued her, his innocence, his gentleness (reminiscent of her father’s), and his evident vulnerability calling forth her own. Their marriage, which took place in 1956, was founded, though it is impossible to know how consciously, on a rejection of everything Murdoch’s experience with Canetti and the line of demon-lovers that led up to him represented. They moved out of Oxford, in part to distance Murdoch from the continuing solicitations of her still numerous admirers. She kept her position at St Anne’s for another seven years before resigning to take a very different kind of position at the Royal College of Art in London, where she taught for four years.

She was putting more of her energies into the writing of her novels, which, after the tremendous success of Under the Net in 1954, would appear very regularly, one a year, or very nearly, until the late 1970s. Her production then began to moderate. She had wanted to be like Tolstoy, like Shakespeare; she had wanted to write a masterpiece. She was capable of mocking her own literary eccentricities (notably in those of the two fictional novelists Arnold Baffin and Bradley Pearson in The Black Prince), but as friend after friend told her her novels were bad, she became prickly. Her volumes of philosophy, The Sovereignty of Good and Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals, were more highly regarded by the non-academic public than by most of her academic peers. She won the Booker Prize for The Sea, The Sea in 1978 and was made a CBE in 1976, then a Dame in 1987. In the last decade of her career her novels noticeably weakened, the prosiness, the didacticism, and the reliance on whimsy, allegory and magic gradually and tediously overwhelming the hilarity, the perfection of tone, the witty throwaway symmetries of accident and insight, the artfully balanced (and, for Murdoch, guiltily gratifying) rhythms and geometries of passion and form of which she had, at her earlier best, been a master. Her old admirers might have read the last novels groaning, but it was Murdoch, after all, and therefore impossible not to read. But by the time Jackson’s Dilemma came out, even those of us who knew nothing of her life other than the version on the jackets of her books recognised that something was very badly wrong.

There is more, however, and more and more: the evidence of erotic excess. Bayley alluded to this excess in his memoirs; Richard Eyre’s film Iris (2001) offers a sliver. But neither gives anything like an adequate sense of the scale of it, and it is impossible to do so here. Not even Conradi himself can quite manage it: his six hundred or so pages are too few for what he has to tell, and his efforts resemble those of a man sitting on a hopelessly overstuffed trunk in an attempt to make it close. It can’t: it is crammed with lovers packed in tight, the details smashed flat, extraneous facts shorn away to save space, mangled and compressed to the point of incomprehensibility and all beyond counting or collating. Behind every layer of involvements and subinvolvements and distractions from involvement there is another layer of involvements and subinvolvements, and behind that another still, each new layer coming as a complete surprise no matter how predictable its emergence ought to be after so many hundreds of pages, and all the more ridiculous for Conradi’s apparent hope – as he slips in yet another brief allusion to the revival of relations with some fellow with whom we haven’t up until now been given reason to suspect Murdoch had ever had any relationship at all – that we might not notice. Not even Murdoch’s own novels, which Conradi shows to be far more nearly realistic in this respect than her critics could have guessed, can compete in erotic complexity with her life.

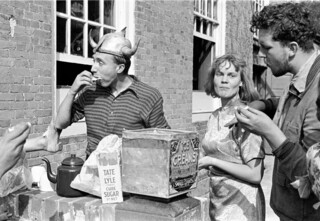

Murdoch had begun her romantic life (so Bayley told the Mail on Sunday) with an attachment to a slug; her first semi-serious schoolgirl romance, largely epistolary and wholly innocent, involved a dentistry student so extravagantly fond of blank verse that he was later to compose his first lecture as a professor of dental anatomy in it. But when Murdoch went to Oxford she unleashed her heart, and unleashed it remained for the next quarter of a century. Though she was by conventional standards closer to plain than to pretty and had a gait, somebody once remarked, like the oxen in Homer, she nonetheless radiated erotic significance. People felt it in her, just as she felt it in them: there was something here that mattered, though what it was remained impossible to convey in words. (Pictures are something else. The photographs Conradi includes are themselves worth the price of the book.) At Oxford especially, virtually everyone she had anything to do with fell in love with her. Conradi compares her to Zuleika Dobson. She had marriage proposals the way some people have hiccups. She had only to ride by on a bicycle or lean an elbow on a table during a lecture to become an object of fascination. One otherwise apparently normal young man glanced out a window, caught a glimpse of her as she passed by – an unknown young woman in an academic gown walking with a friend – and immediately jumped up, ran outside, and followed her into Fraenkel’s Agamemnon seminar, where the young infatuate proceeded to ignore Fraenkel and to look at her, entranced, until the seminar ended. Often enough she seems to have done nothing in particular to invite this interest. The mere sight of her was enough. But once opportunity offered she was incapable of refusing: ‘There has never been a moment when I have trembled on the brink of such an exchange and drawn back,’ she wrote of one admittedly foolish out-of-nowhere kiss. ‘One of my fundamental assumptions is that I have the power to seduce anyone,’ she wrote another time. As one of the many men she was engaged to remarked, she was ‘monumentally unfaithful’. She made a joke about ‘there having been only one man in Oxford she had not had an affair with’. These affairs, some of them lasting for years, others hours, most of them kept secret from the participants in rival affairs, ran not just serially but also simultaneously, in packs or even swarms. She slept with strangers and friends, men and women. Nor, though it certainly diminished, did the promiscuity end when she married. Her affair with Philippa Foot was an event of the late 1960s. Bayley represented her leaving St Anne’s as a decision she made in order to concentrate on her writing, but not at all: she left after being warned that a long-evolving obsessional relationship with a colleague there – the model for Honor Klein of A Severed Head, Conradi suggests – was causing scandal.

It is not at all clear what motivated her in her relations with her lovers. The possibly untrustworthy and certainly fragmentary record of what she felt during those years, when at any given moment she was in love in a dozen different directions at once, is bewildering. Conradi suggests that the appeal of these relationships for her was usually ‘intellectual and moral’, and there is reason to believe this was a factor in some cases. Meeting Fraenkel again in the 1960s after years of estrangement (she had resented his criticism of a novel of hers containing a character she had based on him), she remarked: ‘When I am with him knowledge & ideas seem to flow from him & into me quite automatically. Great teacher, great man . . . I love him, & love him physically too.’ Affection and admiration almost invariably felt to her like erotic attraction. But often enough all a beautiful young thing had to be was beautiful. Though she behaved at times as one frantic for love, she couldn’t always respond in kind to offers of love, and a number of relationships had more to do with domination and submission than with happiness or affection. Bayley doubts that sex was ever important to her, and by 1968 Murdoch looked back to judge all ‘that business of falling in love with A, then with B, then with C (all madly) . . . a bit sickening’. At various times she described herself as a libertine, as a stranger to passion, as a narcissist, as a sadomasochistic gay man, as a corrupter of love, her ‘generosity, gentleness, douceur, tendresse’ turning dangerous, ‘especially in their corrupted form in me’. To one lover she wrote: ‘I still make my love very seriously & let it tear my guts out every time.’ But after Steiner’s death her own toughness appalled her: ‘The horror of feeling indestructible. I can bear all this grief and more without breaking.’ And she could compare a former lover, Conradi writes, ‘to a great fish she had seen dying by the river, and [wonder] why she did not feel more distress. (Of another lover who stayed “stricken”, she commented coolly that it was like knocking someone down and then coming back, years later, and finding them still suffering by the roadside.)’ Yet with very few exceptions her former lovers remained her friends.

‘There are not many people whom one wants to know one!’ she told her journal in 1971. Despite the apparent openness to others, she was careful to preserve her privacy, her guard dropping, slightly, only when she felt protected by distance either generic (as in letter-writing or fiction-writing) or geographic. She had always destroyed letters she received from other people, and when she and Bayley were preparing to move back to Oxford in 1985 she went to work on her journals with a razor blade, destroying materials throughout but concentrating particularly on what she had written during the war and during another period beginning in 1972. The large fact of her three-year affair with Canetti was unknown to any friend Conradi was able to contact as late as 1999.

Her powers of reticence, effacement, and disguise were immense and could be directed against herself as well as against others. ‘I haven’t a face any more,’ she wrote to Thompson. In 1970 she noted: ‘I have very little sense of my own identity. Cd one gradually go mad by slowly losing all one’s sense of identity?’ In 1989 she told an interviewer: ‘I don’t think of myself as existing much, somehow.’ Bayley reports that she lacked what he calls ‘stream of consciousness’; the internal voice that comments on the self and its sensations, she told him, was silent in her. Believing introspection invites drama and self-delusion, she judged it better not to pay much attention to oneself. It is the same in her fiction; the characters whom Conradi says Murdoch identified as her fictional doubles are those whose being it is hardest to imagine or even to want to imagine: Hannah Crean-Smith from The Unicorn, with her tainted, disquieting victimhood, the hideously destructive Morgan from A Fairly Honourable Defeat, and the emotionally opaque Anna Quentin from Under the Net. Murdoch invites no one to enter her reflections. ‘It is good to declare a blankness now and then,’ one of her creatures tells another. ‘We are not anything very much.’

Conradi is fine at summing up the social and intellectual worlds in which Murdoch moved. We learn a lot about the political atmosphere of Oxford, the number of homeless people in London during the war, what she could see out of her window and where she went to fetch water when she was living in her favourite London flat, how (in moving detail, because she didn’t cut up his letters) Frank Thompson felt about her, how (in even more moving detail, because he left a journal) Franz Steiner felt about her, how Murdoch’s friends and acquaintances conducted their friendships and quarrels with one another, even how her friend Janet Stone bought her clothes (by mail order). We learn that people around her found her naive, aboriginal, virginal (long after the facts indicated otherwise), powerful, gentle, extraordinarily kind (unless she wanted your husband), shy, confident, uncensorious, harmonious, inspired, unpretentious, ‘a golden girl for whom the waters parted’, a fairytale princess, a little bull, a lioness, a water-buffalo. We learn that she had a quality of ‘luminous goodness’ and that ‘when she came into a room, you felt better.’

But for all the admirable work Conradi has done among archives, private letters, and those papers that escaped Murdoch’s censoring razor blade, and for all the years of friendship Conradi shared with her, we have here a woman seen for the most part from a distance, the proportions of her story all too evidently (though understandably) a function of the relative availability or unavailability of biographical material. Still more information of the kind those razored bits might have represented could not remedy her essential unknowableness; nor would a different biographical sensibility. The Saint and the Artist proved Conradi’s quiet ability to convey what is most important about Murdoch. So when Conradi insists on his feeling that he never understood her – a bafflement he shares with her friends and even with her husband – it is something to take seriously.

Murdoch herself, or what it felt like to be her – which any biography-reader, no matter how sophisticated, tactlessly and incorrigibly wants to discover – is elusive. It is impossible to imagine what it must have felt like to her to be luminously good, or to seem so, or to walk into a room and make everyone feel better. Possibly we would need to be luminously good ourselves in order to understand. Or possibly we might in this case consider adjusting our sense of what understanding someone means.

Love is the usual clue to understanding – telling us that A is close to so-and-so’s heart, B less so, and C abominable, so that one begins to guess at a structure of intimacy and exclusion, of surfaces and depths and loyalties and aversions. But love gives us a different kind of clue where Murdoch is concerned. With Murdoch love leads not somewhere in particular but seemingly everywhere, to A and B and C, right on down the alphabet. Everything is equally inside the space of her attention: spider; slug; Canetti (and his maimed wife and his dying mistress); the Agamemnon; Bayley; the mouse that ran unnoticed up Bayley’s arm one day while he was looking at badgers and then across his collar and down the other arm, still unnoticed; the badgers themselves; her friends the teacups and spoons; the scrap of paper she could not bring herself to burn. Her affections are like the glittering tangles one of her characters watches another comb delicately from his hair, floating to the floor but glimpsed again later in ‘the gleaming fuzz of innumerable stars’ in the Milky Way, wheeling through ‘the deep absolute darkness that hid other and other and other galaxies’, a cosmos accidentally imaged in the most accidental of forms, the likeness itself neither fully meaningful nor completely absurd, not a marriage but a kiss.

‘Art invigorates us by a juxtaposition, almost an identification, of pointlessness and value,’ Murdoch writes. Her tangles turn sometimes into galaxies and (since transfiguration, a ‘simulation of the self-contained aimlessness of the universe’, is as likely to tip backwards as forwards) her galaxies sometimes into tangles. Her ecstatic visions are never the last word. Ecstasy itself is suspect until it is reabsorbed into ‘the bafflement of the mind by the world’, into the ‘ordinary human jumble’ that is its source and – if the vision is true – its only valid sense. All this contributes to the notorious difficulty of discussing her work without sounding befuddled. Writing of the novels in The Saint and the Artist, Conradi observes: ‘the truths they mediate turn out often to be as simple as “Nobody’s perfect” or “Handsome is as handsome does.” That such dull commonplaces can radiate as much light as apparent profundities is her point.’ He is entirely right – and admirably reasonable. But embarrassed in my efforts to translate a prolonged and helpless infatuation with the novels into something resembling sense, I feel closer to the doomed Murdoch character on an LSD trip, as he tries to describe to his non-tripping friend his blissful insight into the nature of things:

How things are. They are in themselves, they are, I say, in themselves, that’s the – the secret . . . They are not just in themselves – they are – themselves. Everything is – itself. It is a – itself. But, you know, there’s – there’s only one . . . Anything. Everything is – all together – like a big – it’s shaggy –

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.