In his account of late capitalism Fredric Jameson describes its cultural logic as if it were a schizophrenic – broken in language, amnesiac about history, in thrall to glossy images, subject to mood-swings from speedy euphoria to catatonic withdrawal. No wonder that his exemplar is Andy Warhol. ‘Warhol distrusted language,’ Wayne Koestenbaum writes on the first page of his smart biography; ‘he didn’t understand how grammar unfolded episodically in linear time, rather than in one violent atemporal explosion. Like the rest of us, he advanced chronologically from birth to death; meanwhile, through pictures, he schemed to kill, tease and rearrange time.’ Signs of this linguistic disturbance, real or staged, are abundant. There is ‘virtually no correspondence in his hand’: photographs, audiotapes and films were his modes of inscription. He couldn’t spell to save his life: typographic errors recur in his commercial illustrations of the 1950s, sometimes introduced by his Czech mother, Julia. And he spoke in a deadpan that extended to his books, which were mostly edited from taped conversations. All of this evidence leads Koestenbaum to his initial diagnosis of Warhol: ‘Trauma was the motor of his life, and speech the first wound’ – speech understood here as the medium of ‘normal’ intersubjectivity or reciprocity with the world.

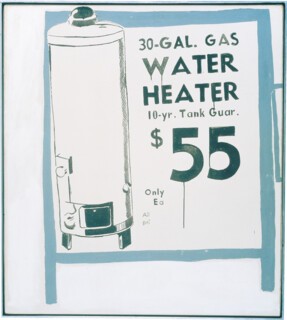

‘Trauma’ is the lingua franca of much cultural analysis today, and it is not new to Warhol studies either. From his mother’s colostomy bag (she had colon cancer) to the brutal scars that tattooed his torso (he was shot, almost fatally, in June 1968), wounds figure literally in Warhol. A 1960 painting, based on a newspaper ad for surgical trusses, asks prophetically ‘Where is Yo Rupture?’, and Warhol always seemed to pick out the telling cracks in images and in people, whom he often regarded as another species of image. Metaphorically, too, as a breaching of interior and exterior, trauma can be seen as the very operation of his art. ‘It’s just like taking the outside and putting it on the inside,’ Warhol said early on about Pop, ‘or taking the inside and putting it on the outside.’ This elliptical remark might be understood literally – at one point Koestenbaum interprets his ‘entire oeuvre as an externalisation, crisply distanced and disembodied, of his abject internal circuitry’ – or again metaphorically, with his Pop images seen to register the delirious confusions between private and public that first became pronounced in this era: that is, between the desires and fears of the individual subject and the commodities and celebrities of consumer society, of which Warhol was the great portraitist. In either case he appeared ‘porous’ in a strange, new, near-total way: porous both in his art, with its steady stream of Pop effluvia (from his early Campbell’s Soup Cans to his late Diamond Dust Shoes), and in his life, with his studio, dubbed ‘the Factory’, set up as an open playground for subcultural denizens, mass-cultural divas, and ‘superstars’ of his own making.

At the same time Warhol was the opposite of porous. Especially after his shooting by the paranoid Factory fade-out Valerie Solanis, he countered his vulnerability with psychological defences and physical trusses of different sorts: buffering entourages, opaque looks (big glasses, silver wigs), protective gadgets (the omnipresent Polaroid and tape recorder), plus a weird ability to pass as his own double or simulacrum (even when he was right there in front of you he seemed somehow disembodied). And these devices became central to his persona, which is sometimes seen as his ultimate work: Warhol as the spectral centre of a flashy scene, a kind of blank Gesamtkunstwerk-in-person. Whereas Marshall McLuhan, a very different media figure of the 1960s, viewed new technologies as prostheses, Warhol used them as screens. As Koestenbaum writes, the dominant strategy of his Pop was to combine ‘lurid subject’ and ‘cool presentation’, and to translate images from one medium or sphere into another in order to ‘embalm’ them – though this embalming could also infuse his images with a psychic charge, an unexpected punctum, as Roland Barthes might say. Think of the two housewives in Tunafish Disaster (1963), victims of botulism taken directly from a newspaper page; smeared across the silkscreened painting, their smiling faces become piercing in repetition.

From the early days of the Factory on, Warhol always recorded: visitors were often placed in front of a movie camera in a ‘screen test’ that also served as an initiation rite. And especially in his last years he collected compulsively: when the going got rough, Warhol went shopping, and his townhouse became filled with sets of kitschy things like cookie jars which were auctioned off after his sudden death in 1987. For Koestenbaum, this endless taping-and-filming and buying-and-bagging point to a subconscious plan to ‘conquer by copying’ or to control by gathering. Here what counts as ‘putting in’ or ‘taking out’, as porous or trussed, open or closed, is not clear, but that may be the point: like the two states that underlie them, these two strategies are bound up with each other. In this light his collecting was another way of being porous to the world, and his being porous another way to defend against images and objects – that is, to drain them of affect, to close them off again. His sayings on this score are well known: from his early motto, ‘I want to be a machine,’ to his late ode to repetition, ‘I like things to be exactly the same over and over again . . . Because the more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel.’ Perhaps it was to this same end that, after 1974, he diarised the bric-a-brac of his life in ‘time capsules’, cardboard boxes filled with mementos and ephemera (there were over 600 in his estate). In a nice twist Koestenbaum adopts a nickname that Warhol dropped early on, ‘Andy Paperbag’, which evokes not only his compulsion to collect but also the fragility of this protective device. More ominously, he writes of the Campbell’s Soup Cans and Brillo Boxes as ‘simulacra of Andy’s body’. Deleuze and Guattari gave us the ‘body without organs’, the subject as a machine of desirous connections; Warhol left us with its quasi-autistic opposite, the ‘box without openings’.

Koestenbaum also relates the proclivity for ‘multiplication and archiving’ to gay taste in New York, which in ‘the bleak McCarthy era paradoxically flourished in the home’. In this ‘domestic avant-gardism’ public signs were ironised in private ways that ‘interrupted the distinction’ between the two spheres. Such customising of images is close to ‘camp’ as defined by Susan Sontag. Alert to the queer dimension of this sensibility (her celebrated 1964 essay reads in part like a field report on the gay underground of Warhol, the filmmaker Jack Smith and others), Sontag saw camp as ‘dandyism in the age of mass culture’ – that is, as a way of wresting the distinctive from the vulgar, of finding feeling in kitsch, of transcending ‘the nausea of the replica’. Some of this spirit, such as the attraction to degraded imagery, is maintained in Pop, but much is not: Pop hardly redeems sentiment, and it does not transcend the nausea of the replica so much as rub our faces in it. Here Koestenbaum shifts the lines that have long defined Warhol studies, away from breaks in style such as Abstract Expressionism v. Pop, and towards (dis)continuities in sensibility across his campy commercial work of the 1950s and his cool artwork of the 1960s.

Trained at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon), Warhol moved from Pittsburgh to New York in 1949, and shed his ethnic identity then, too, dropping the final ‘a’ from his name. He fared well as a commercial illustrator, with adverts done for Harper’s Bazaar, Seventeen, the New Yorker and Vogue, displays for Bergdorf Goodman, Bonwit Teller, I. Miller and Tiffany & Co., as well as book jackets, record covers, stationery and the like. Warhol received three Art Directors Club awards in the 1950s, and he continued in this mode well into the 1960s – an often overlooked fact – through 1962, when the Campbell’s Soup Cans appeared; 1963, when the films began; 1964, when the Brillo Boxes were done; and so on. Moreover, as Koestenbaum argues, Warhol was ‘more of a fine artist in the 1950s’ as a commercial illustrator than in the 1960s as a Pop artist, if by ‘fine’ we mean the apparent signs of craft, handwork and subjective expression. And the reverse is also true: his great silkscreens begun in 1962 show a ‘designer’s intelligence’, and, as Benjamin Buchloh has written, his Pop art carries over traits of his commercial illustration: ‘extreme close-up fragments and details, stark graphic contrasts and silhouetting of forms, schematic simplification and, most important, rigorous serial composition’. The imbrication of the two practices was persistent: his first show of Pop paintings was a window display at Bonwit Teller in 1961, and after 1968 he returned to a mode that he never really left – ‘business art’. Until recently, art history has mostly glanced over the commercial design in some embarrassment (at least Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had the good taste to treat their window displays as rent-money work), sidelined the films and bemoaned his supposed decline after the 1968 shooting. Along with a few other contemporaries, Koestenbaum writes against all three biases.

Until recently, too, art history liked to suggest a clean break between the aftermath of Abstract Expressionism and the rise of Pop, and it pounced on a particular anecdote to firm up this stylistic divide. In 1962, Warhol showed two paintings of a Coke bottle, first to the filmmaker Emile de Antonio, then to the dealer Ivan Karp, and asked them which he should exhibit. (This is a classic instance of his deferring of responsibility. Marcel Duchamp exacerbated the problems of artistic making and judging with his ready-made objects: ‘Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain or not had no importance. He chose it.’ Warhol complicated aesthetic choice further by passing it off, or at least around, often to his assistants.) One of the Coke paintings has painterly drips that might read as signs of expressive gestures, while the other is almost as pristine as the commercial original, right down to the registered trademark. His friends opted for the iconic Coke, and Pop was born. Although now sealed with the false obviousness of history, this story was always too convenient by half. Even more blatantly than his gay predecessors Rauschenberg and Johns, Warhol derailed Abstract Expressionism stylistically (though it had also run out of track by then); the crucial question is what drove this turn.

Here another juxtaposition, made by Rosalind Krauss, is telling. In the early 1960s Warhol continued the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock by other means: he peed onto canvases which were covered with metallic paint and set on the floor – or had his Factory workers pee (even here he deferred). The paint oxidised into misty veils or, when his female associates peed, murky puddles. These paintings ‘queered’ the drip paintings: suddenly the machismo of the Pollock gesture looked a little impotent, and the homosocial dimension of the old Abstract Expressionist circle like a circle-jerk (primal boys peeing on fire). The piss paintings also forced a double-take on the apparent purity of Colour Field painting, on the poured veils of Morris Louis and the stained grounds of Helen Frankenthaler; and when Warhol did more such works in the late 1970s, Neo-Expressionist painting looked even more absurd than it did before. As critics such as Douglas Crimp and Richard Meyer have stressed, this queering of art was also a matter of content. If the persona behind Abstract Expressionism was the ‘action painter’ in existential torment, Warhol put pretty-boy idols of mass culture up front, such as the young Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty, Elvis and Brando, all subjects of early silkscreens. More notoriously, he did the same with the not-so-pretty Thirteen Most Wanted Men, the FBI mug-shots that he silkscreened for the façade of the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair (they were covered up by order of Commissioner Robert Moses, who was not amused when Warhol offered to substitute an image of him instead). Here he turned the meaning of ‘most wanted’ inside out: these men might be ‘wanted’ sexually, too – might be ‘criminals’ in a double sense.

The queering did not stop there. As Annette Michelson argues, the Factory was a semi-conscious mockery of Hollywood cinema and culture industry alike. For instance, in many Warhol movies ‘montage’ means the simple splicing together of unedited rolls of film (Empire, made in 1964, is a fixed stare at the Empire State Building that lasts for 24 hours); few have stories, let alone scripts, and some are porn. Moreover, Michelson sees the Factory as a latter-day experiment in Bakhtinian reversal: with its ‘parodistic procession of divas, queens and superstars’, and spectacular mixing of uptown society, 42nd Street riff-raff and downtown bohemia, it resembled a court turned into a carnival. ‘In carnival,’ she writes, ‘behaviour and discourse are unmoored, as it were, freed from the bonds of the social formation. Thus, in carnival, age, social status, rank, property, lose their powers, have no place; familiarity of exchange is heightened.’ The strategy of the Factory was indeed ‘super’ – to hyperbolise roles in a way that sometimes mocked them. But this parodistic play with the social order was only half-intended; it was also sporadic and short-lived, and by the time of the Interview magazine of the Reagan years it had swung over to its opposite: hero-worship of the rich and famous. So, too, the tropes of carnival, ‘travesty and humiliation’ above all, often rounded on Factory dwellers; as Koestenbaum suggests, this scene could also be cruelly hierarchical – very different from the cosy milieu of the commercial-illustration days.

Koestenbaum sees both continuity and discontinuity here: even as the Factory ‘extended the apartment philosophy Warhol first learned from decor-conscious gays’, it diverged from the campy sensibility of his design studio. In his Diaries (1989) Warhol refers this break to the death of his favourite cat in the early 1960s: ‘My darling Hester. She went to pussy heaven. And I’ve felt guilty ever since . . . That’s when I gave up caring.’ This is a mock-traumatic account, of course; affect did not die with Pop, but it did take on a torturous turn in the Factory. This is so in part because the Factory was given over to ‘performance’ in the sense not only of performance art (all the screen tests and films, the live theatre and ‘Exploding Plastic Inevitable’ events featuring the Velvet Underground) but also of performed identity. ‘To work for Warhol was to lose one’s name,’ Koestenbaum comments; and Billy Linich, the de facto manager of the Factory, became ‘Billy Name’, as Robert Olivio became ‘Ondine’, the heroine of a: a novel (1968), Susan Hoffmann ‘Viva’, the star of several films, and so on. This renaming was one prerequisite to superstar status, and it was often bound up with regendering: to ‘swing both ways’ was to play with both semiotic and sexual designations. This was the carnivalesque moment par excellence, and it had obvious risks, especially when mixed with pill-popping and vein-poking, bohemian showmanship and media spotlights.

In short, there was a psychological volatility of roles in the Factory, which sometimes sounds like a desultory S/M theatre, with Warhol as a director both kind and cold, passive and aggressive. He would goad people into defensive or outlandish performances, especially in the films (some of which also thematise bondage), as if to film was to provoke and to expose, and to be filmed was to parry this attack. Koestenbaum is good on this ‘emotional oscillation’; he catches the tension between inhibition and excess, ‘diffidence and exhibitionism’, deathly stillness and sexual motility, and argues that it could induce a ‘paranoid relation’ to whomever acted out on the screen or in the Factory at large. But the movies also produce a different sort of connection: the viewer does not identify with the filmed subject in the manner of classic Hollywood cinema, of course, but rather empathises with the travails of being before a relentless camera, with the vicissitudes of becoming an image, with wanting or resisting this condition too much.

According to Koestenbaum, Warhol always had a particular target in his sights – masculinity – and a particular way to mess with it, which he terms ‘twinship’. ‘Masculinity was a subject Warhol failed from the start,’ Koestenbaum writes; his art became ‘the sexualised body his actual body largely refused to be’. In this regard, too, ‘Andy liked to entrust others with the task of embodying Andy,’ and often this embodying involved ‘female dopplegangers’ like Edie Sedgwick whose ambiguity as both femme and boyish did a number on gender. Koestenbaum refers this ‘twinship’ to a ‘hom0erotics of repetition and cloning’, but it might also be seen as a play with kinds of likeness that are only like enough to be subversively other. This doubling-with-a-difference runs throughout Warhol: both in his life, where he was mirrored, weirdly, by Edie, Nico and others; and in his art, where the silkscreens are often instances of image repetition run amok, and the films are often double projections in which the ‘action’ in one screen has little or nothing to do with that in the other. Koestenbaum describes this trait as ‘nonparticipatory adjacency’, and in a sense it structured the entire Warhol world: he spent days at the Factory with image-producers and scene-makers; evenings first at the bar-and-restaurant Max’s Kansas City and later at the club Studio 54 with the entourage; nights at home on the Upper East Side with Mom and the cats; and Sundays at Mass (he remained a Catholic to the end).

At first Warhol projected onto celebrities; later he painted them; in time ‘he merely needed to stand next to them . . . his Andyness could sign the adjacent presence, make it Andyish.’ Here, too, doubling was the primary Warholian device. (For me it became delirious one night in the early 1980s at a club called Area, as I watched Jean Baudrillard, the theorist of the simulacrum, watching Warhol posing as ‘Warhol’ in a bare diorama of his own making, as if he were the wax model of his own dead specimen. I thought one of them would have to explode.) ‘Pop art rediscovers the theme of the Double,’ Barthes once wrote, but it has ‘lost all maleficent or moral power . . . the Double is a Copy, not a Shadow: beside, not behind: a flat, insignificant, hence irreligious Double.’ I’m not certain about this last point. In the Factory Warhol was called ‘Drella’, a fitting contraction of Cinderella and Dracula, for like the former he lived the dream of going to the ball (and sometimes getting the prince), and like the latter he sucked the blood of others in a way that left him ravished too. This deathly doubling is one reason why Warhol remains so fascinating: more than anyone else he acted out the strange mass subjectivity of the Pop image-world. As Michael Warner has argued, ‘to be public in the West means to have an iconicity . . . In the figures of Elvis, Liz, Michael, Oprah, Geraldo, Brando and the like, we witness and transact the bloating, slimming, wounding, and general humiliation of the public body. The bodies of these public figures are prostheses for our own mutant desirability.’ Warhol operated on both sides of this equation: he was a ‘mutant desirer’ first and last, but he also became a mass icon in his own right; indeed after his shooting he entered the pantheon of martyr-stars (Liz, Marilyn, Jackie) that he also portrayed.

Like Christ (here Koestenbaum stretches for a parallel too far, but why not?), Warhol became more iconic as his body became more ravaged. He took on a ‘revenant appearance’, and delivered works possessed of ‘the shadow aura of bulletins from the afterlife’, paintings of Skulls (1976) and Shadows (1978) in particular; appropriately, he was at work on a wallpaper version of the Skulls – portraits of us all in effect – at the time of his death. Unlike the Pop of Roy Lichtenstein or James Rosenquist, his Pop had teeth, and a great part of its edge lay in its recognition of the deathliness of the mass image. On this score the best remark comes from Deleuze in 1969, in the middle of the Vietnam War, no doubt with Warhol in mind:

The more our daily life appears standardised, stereotyped and subject to an accelerated reproduction of objects of consumption, the more art must be injected into it in order to extract from it that little difference which plays simultaneously between other levels of repetition, and even in order to make the two extremes resonate – namely, the habitual series of consumption and the instinctual series of destruction and death. Art thereby connects the tableau of cruelty with that of stupidity, and discovers underneath consumption a schizophrenic clattering of the jaws, and underneath the most ignoble destructions of war, still more processes of consumption. It aesthetically reproduces the illusions and mystifications which make up the essence of this civilisation, in order that Difference may at last be expressed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.