When René Goscinny, the creator of Astérix, died in 1977, it was, in the words of one French obituary, ‘as if the Eiffel Tower had fallen down’. The cartoon adventures of the plucky little Gaul holding out against Roman conquest (with the help of a magic potion that could confer a few minutes’ irresistible strength at a single gulp) were as much a defining part of French cultural identity as the most distinctive monument on the Paris skyline. A national survey in 1969 suggested that two-thirds of the population had read at least one of the Astérix books; and by the time of Goscinny’s death total sales in France are said to have amounted to more than 55 million copies, putting Astérix substantially ahead of his main (Belgian) rival, Tintin. The first French space satellite, launched in 1965, was named in his honour (the US later matched this with spaceships called Charlie Brown and Snoopy). There was also, predictably, a more mundane range of Astérix spin-offs, from mustard to washing powder, that flooded the French market in the 1960s and 1970s. The story goes that Goscinny’s partner, Albert Uderzo, once saw three advertisements side by side on a Métro station, for three completely different products each endorsed with equal enthusiasm by Astérix and his cartoon comrades. From then on, they put much tighter limits on the products they would allow their hero to advertise.

Goscinny was born in Paris in 1926, divided his childhood between France and Argentina, and learned the cartoon trade in New York, with the group of artists who went on to found Mad magazine. Returning to France in 1951, he teamed up with Uderzo – Goscinny wrote the words, Uderzo did the drawings. They had a dry run for Astérix with a short-lived cartoon called Oumpah-pah, featuring a Flatfoot Indian living in a remote village in the Wild West that was bravely holding out against the palefaces, but struck lucky when they launched their ancient Gaulish version of Oumpah-pah in 1959 in the first issue of the comic Pilote (which, like Mad, was aimed at adults rather than children). Pilote had the financial backing of Radio Luxembourg; and the instant success of the magazine and its cast of characters can hardly have been unconnected with the barrage of publicity provided by the radio station.

Their first fully-fledged book, Astérix le Gaulois, appeared in 1961; and at the time of his death, 16 years later, Goscinny had just completed the script of the 24th, Astérix chez les Belges – a swashbuckling adventure with some remarkably stereotypical Belgians, large quantities of beer and Brussels sprouts, plus the inevitable walk-on part for a pair of Tintin characters. This was almost the end of Astérix. Goscinny died before the book had been illustrated, and Uderzo was extremely reluctant to finish the job. But the publishers could not afford such sentiment and took him to court to try to force him to produce the drawings. They won the first round of the legal battle and Uderzo grudgingly turned his hand to the work. Ironically, the book had already been published when he got the judgment overturned on appeal. The last 25 years have seen Uderzo (now well into his seventies) repeatedly retire, declaring the series over, only to come back a few years later with a new, solo-authored adventure. Meanwhile, he has been cashing in on the phénomène Astérix with an unusually tasteful theme-park, Parc Astérix, just outside Paris, and a run of movies. The latest, Astérix et Obélix: Mission Cléopatre opened in Paris last month and stars, for the second time, Gérard Depardieu as an appropriately portly Gaul.

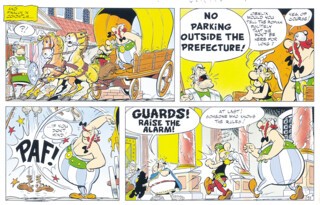

For fans of Astérix the big question is whether the books by Uderzo alone are any match for the ‘classics’ produced when the partnership was in its prime: Astérix Gladiateur (in which our hero enrols as a gladiator in order to rescue the village bard, captured by Caesar); Astérix et Cléopatre (the basis for the new movie, ‘the most expensive French film ever made’, in which Astérix and friends visit Egypt and find themselves in a hilarious parody of Mankiewicz’s epic movie); Astérix chez les Bretons (in which a Gallic mission to take the magic potion to the struggling Britons ends up with Astérix teaching them how to brew tea). Before Goscinny’s death Uderzo had never taken much part in the writing and to judge from his latest, Astérix et Latraviata (translated into English as Asterix and the Actress), the answer to the big question would be a disappointing no. The satire is stale. The storyline is over-complex and under-engaging. It starts with the (joint) birthdays of Astérix and his best friend Obélix, the menhir delivery-man; their mothers arrive full of ideas about getting their boys married off at last, while their fathers, too busy selling souvenirs in the local oppidum to join in the celebrations, send a splendid sword and helmet as a present; these turn out to be the stolen property of a Very Important Roman; the fathers end up in prison for the theft, while the Romans dispatch an actress, disguised as Obélix’s heart-throb, Falbala (‘Frippery’ – the translators call her ‘Panacea’), to try to wheedle the weapons back; inevitably, the real Falbala turns up and the obvious confusions follow. It reads rather like a bedroom farce sprinkled with some ponderous lessons in Roman history – one of the most densely packed speech bubbles in the whole Astérix series is here devoted to a breathless, and not entirely accurate, résumé of first-century BC Roman politics: ‘Once upon a time Rome was governed by a triumvirate . . . that means three consuls etc etc,’ as Astérix explains to an understandably bemused Obélix.

Uderzo’s form has not always been so poor. Some of his earlier efforts proved to be elegant sequels to the joint series, neatly in tune with the changing politics, and fashions in humour, of the 1980s and 1990s. L’Odyssée d’Astérix (Asterix and the Black Gold) sends the Gauls to the Middle East in search of a mysterious vital ingredient for the magic potion (petroleum, as it turns out) and brilliantly takes on the oil industry, pollution and the intricacies of Middle Eastern politics; on the way home with their precious cargo, a nasty mishap in the Channel produces the world’s first oil-slicked seagull. A turn to the Postmodern has become increasingly evident. ‘I’m not enjoying this adventure very much,’ Astérix complains to Obélix halfway through Le Fils d’Astérix (Asterix and Son). ‘Oh it’ll be all right!’ Obélix says to calm him. ‘It’s sure to end with a banquet under the starry sky, same as usual.’ He is referring to the distinctive last scene of every Astérix adventure – except, as the reader will discover, this one.

The even bigger question, though, is why these cartoon stories of ancient Gauls and their unfortunate Roman adversaries ever became so successful. Goscinny and Uderzo themselves always refused to show much interest in this. Confronted by interviewers suffering, as they saw it, from ‘exegesis sickness’, they would counter with a bluff, no-nonsense (and, I hope, ironic) lack of curiosity. People laugh at Astérix, Goscinny once pronounced, ‘because he does funny things, and that’s all. Our only ambition is to have fun.’ On one occasion a desperate interviewer on Italian television suggested (not very subtly) that the appeal of Astérix’s struggle against the Roman Empire was something to do with the ‘little man refusing to be crushed by the oppressive weight of modern society’. Goscinny crisply replied that, as he didn’t travel to work by the Métro, he didn’t know about little men being crushed by anything.

Most critics, on the other hand, have thought that there was a good deal that needed explaining. Some, like the Italian interviewer, have dwelt on the appeal of the David-and-Goliath conflict between the Gauls and the Roman superpower. Or, at least, David and Goliath with a twist: Astérix doesn’t beat brute force by superior cunning and intelligence – he does it thanks to his unexpected access to even bruter force than the enemy can deliver. In adventure after adventure, most of the Gauls’ over-ingenious schemes misfire as badly as the best-laid Roman ones. The reassuring fantasy is that, thanks to the magic potion, Astérix and his friends can mess things up and still win out.

Others have made a lot of the cartoon’s attraction for adults, as intended by the original Pilote. The books are littered with wry references to contemporary French culture and politics: Jacques Chirac’s economic policy was thoroughly taken apart in Obélix et compagnie, with Chirac himself recognisably caricatured as a pretentious Roman economist; and the café in Marseille where Astérix and Obélix stop over in Le Tour de Gaul (Asterix and the Banquet) is, for those in the know, an exact copy of the one that features in the film of Pagnol’s Marius. (Pagnol was apparently delighted: ‘Now I know my work will be immortal.’) There is also a whole series of clever parodies of classic works of art, even if these are not quite so thick on the ground as Astérix’s most intellectual fans would have us believe. By far the cleverest is the reworking of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa as a lifeboat for a ramshackle and disgruntled party of pirates in Astérix légionnaire (‘Je suis medusé’ – ‘I’m medusa-ed/dumbfounded’ – one of them shouts out for the benefit of those who’ve failed to spot the reference). This adult appeal is obviously a crucial factor in the books’ sales, given that most child readers are dependent on adult purchasing power. As Olivier Todd once said, parents read Tintin after their children: they read Astérix before the children can get their hands on the books.

Another crucial factor must be the history that Astérix both recalls and satirises. Just as 1066 and All That depends on our familiarity with the images and stories of British history that it parodies, so Astérix takes its French readers back to a moment they all know: when, according to the French school curriculum, French history starts. ‘Nos ancêtres les Gaulois’ is a slogan drummed into children by countless textbooks; and the key figure among these early ancestors is Vercingetorix, leader of the Gauls in a notable rebellion against Julius Caesar in the late 50s BC. Vercingetorix is written up in Caesar’s own self-serving account of the Gallic War as a traitor and Gallic nationalist, who was resoundingly outmanoeuvred by Roman tactics at the Battle of Alesia; he surrendered to Caesar and was packed off to Rome, to be killed several years later as part of the celebrations of Caesar’s triumph in 46 BC. In modern French culture, as Anthony King has emphasised (in a recent supplement to the Journal of Roman Archaeology), Vercingetorix has become a national hero for both Left and Right. In World War Two, for example, he did double duty as ‘the first resistance fighter in our history’ and as a symbol for Pétain and the Vichy Government of how to be noble, and nobly French, in defeat. The occasion on which, with all the dignity a failed rebel could muster, he laid his arms at Caesar’s feet, has become a mythic image, one of the key moments in the history of the nation. It appears in the second frame of Astérix le Gaulois, where, in a characteristic twist, Vercingetorix manages to drop the bundle of weapons on Caesar’s toe – so prompting not a victory speech, but a loud ‘Ouch’. In fact, throughout the series Astérix himself can be seen as Vercingetorix’s double, the fantasy of a Gallic nationalist who managed to escape Caesar’s clutches.

But if Astérix is so deeply rooted in French popular culture, how do we explain his enormous success in the rest of the world? (So far as I know, 1066 and All That has never touched much of a chord in France, Iceland or Japan.) Ambitious translation is part of the answer. The English translators of the whole series, Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, have approached the job in the most energetic way. All the French jokes, and in particular the distinctive word plays, are given a new English spin, often with very little link to the original. The names of major characters are regularly changed: the tone-deaf village bard Assurancetourix (‘assurance tous risques’, or ‘comprehensive motor insurance’) has become Cacofonix; the French dog Idéfix turns up in English as Dogmatix. Bell and Hockridge stick faithfully to the spirit rather than the letter of the humour. So, for example, on the Raft of the Medusa, ‘je suis medusé’ is replaced by a suitably English hint at the point of the parody: ‘we’ve been framed, by Jericho!’

The effect of the translators’ intervention is almost always to produce a significantly different book. The classic case of this is Astérix chez les Bretons. In much the same spirit as Astérix chez les Belges, the French original pokes plenty of fun at the British, who are presented as every French cliché has always imagined. They stop for a hot-water break at five (Astérix has not yet shown them how to make tea), they drink warm beer, smother their food with mint sauce and speak a parodic and almost incomprehensible version of Anglo-French. ‘Bonté gracieuse’ (‘goodness gracious’) is a favourite phrase; ‘plutôt’ (‘rather’) follows up many a sentence; and adjectives are repeatedly inserted before their nouns (‘magique potion’ instead of ‘potion magique’). In Bell and Hockridge’s translation, however, waspish French chauvinism is transformed into characteristically English self-deprecation. There was hardly any need for the message from Goscinny and Uderzo included in the first editions of the British translation, assuring readers that the caricature was intended to be gentle and funny; Bell and Hockridge had already drawn its sting.

The basic storylines also reinforce the series’ international appeal, at least in Europe. Intentionally or not, Goscinny and Uderzo exploited the legacy of the Roman Empire across most of the continent. For wherever Roman conquest reached, there are still tales of heroic resistance and glamorous native freedom-fighters. If, for the French, Astérix is inevitably keyed into the story of Vercingetorix, the English can read him as a version of Boudicca or Caratacus; the Germans as a version of their own Hermann (known in Latin literature as Arminius). As for the Italians themselves, they are usually happy to enjoy a joke about their Roman ancestors – particularly when they are presented, as Astérix’s adversaries are, as rather amiable bad guys, held back from serious evil by sheer inefficiency.

The United States is the only country in the West where Astérix has remained a minority taste – despite one adventure that actually took the Gauls to the New World, in an effort presumably to drum up an American readership. This gap in the market has been endlessly and implausibly theorised. Cultural chauvinists in France have liked to believe that Astérix is simply too sophisticated for the Disney-fed masses of America; and they have pointed to the contrast between the relatively elegant, up-market and very French Parc Astérix and the vulgarity of its neighbour, Euro Disney. Others have tried a political explanation, reading the cartoon conflicts between nice Gauls and nasty Romans as a thinly veiled attack on American imperialism and the dominance of the new superpower (hence, they suggest, the unexpected niche market for the series in China and the Middle East). But the bottom line is that Astérix is indomitably European. The legacy of the Roman Empire provides a context within popular culture for the different countries of Europe to talk with, and about, each other, and about their shared history and myths. It would be hard to penetrate that from the other side of the Atlantic.

Across Europe, the story of Astérix has also encouraged many people to think harder about the history and prehistory that it reflects and the myths it embodies. Archaeologists have not been slow to take advantage of the popularity of the series to introduce schoolchildren and parents to the pleasures of museums and site-visiting; a few years ago, for example, a British Museum ‘education pack’ on the Iron Age and Roman-British collections used Astérix as a slogan and front-man – ‘Asterix at the BM’. Ironically, though, the interpretation of Roman history on which Goscinny and Uderzo’s scenario of Gallic-Roman conflict is based has long faded out of academic fashion. Go back forty years or so and you will indeed find archaeologists reconstructing the history of the northern provinces of the Roman Empire largely in the style of Astérix. Roman imperialism was then generally seen in stark, clear-cut terms. It offered the natives of these conquered territories a simple choice: Romanisation or resistance; learn Latin, wear togas, build baths or (in the absence of a real-life magic potion) paint yourself with woad, take to the scythed chariots and massacre the nearest detachment of Roman infantry. It is a choice hilariously dramatised in Le Combat des chefs (Asterix and the Big Fight), which contrasts Astérix’s village with a neighbouring Gallic settlement. If Astérix and his friends have opted for resistance to Rome, the other village has equally enthusiastically embraced Romanisation. We see their native huts embellished with classical-style columns, their chief honoured with a Roman portrait in what must pass for the village’s forum, and their children in school going through the ‘grammar-grind’.

Approaches to Roman imperialism are now more realistic. As we have come to understand it, the Romans had neither the manpower nor the will to impose the kind of direct control and cultural uniformity that the Astérix model imagines. Their priorities were money and a quiet life. Provided the natives paid their taxes, did not openly rebel and, where necessary, made a few gestures to Roman cultural norms, their lives could – if they wished – continue much as before. This new version of Roman provincial life has not yet been immortalised in a strip cartoon. But some years ago the archaeologist Simon James drew a single comic vignette, which has become famous among classicists for encapsulating the new approach to the history of Roman imperialism in the northern provinces. It shows a small native homestead, with a traditional round Iron Age hut and an obviously native family. Next to it runs a Roman road, and just disappearing on their march past the homestead is a party of Roman legionaries (messily dropping behind them the kind of Roman bric-a-brac that archaeologists will eagerly dig up in two thousand years’ time). Between the homestead and the road the canny natives have constructed a huge cardboard cut-out of a classical façade with pediment and columns, which they are gamely holding up to impress the soldiers and temporarily disguise the native life blithely going on behind. But they won’t have to keep the pretence up much longer: ‘It’s all right, Covdob, they’ve gone!’ shouts the native missus to her native husband, as the legionaries pass into the distance. It’s a trick that has not yet entered the Astérix repertoire.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.